INTRODUCTION

Addiction therapists, professionals who provide psychotherapy to persons suffering from substance use disorders (SUDs), are a particular professional group committed to supporting those affected by one of the most stigmatised mental disorders. The few studies conducted among addiction therapists suggest that they are particularly vulnerable to burnout and associated problems [1, 2]. Farmer’s study of the prevalence of occupational burnout in a group of drug treatment professionals found that over 50% reported significantly high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation (also defined as cynicism and detachment) [3]. A UK study identified the prevalence of occupational burnout in three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (33.2%), depersonalisation (17.0%), and lack of personal achievement as a result of critical self-assessment (35.8%) [4]. In a recent Polish study, occupational burnout was found to be highly prevalent among alcohol treatment professionals, with both aspects (i.e., exhaustion and disengagement from work) experienced by a half or more of the respondents [5]. Research in this area shows that occupational burnout is associated with other somatic and emotional problems. The quality of life of those who experience burnout is lower than that of those who do not [6, 7]. Addiction therapists who experience burnout are more likely to report other stress-related and mental health problems, including mood and anxiety disorders [4, 7]. In addition, therapists experiencing occupational burnout are less effective in their therapeutic work and are involved in more team conflicts. As a result, occupational burnout can lead to resignations that disrupt the functioning of the addiction treatment facility [8-10]. High staff turnover affects the work atmosphere and places a higher (albeit temporary) burden on the remaining staff [10]. Furthermore, research shows that therapist burnout results in a slower therapeutic process and lower treatment satisfaction among patients, while high rates of staff absenteeism and lack of continuity of therapeutic care are associated with increased rates of treatment dropout [9, 11].

Occupational burnout is a psychological syndrome that emerges as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal work stressors. The three key dimensions of this response are (1) overwhelming exhaustion, (2) feelings of cynicism and detachment from work, and (3) a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment [12, p. 103]. Maslach’s model places the individual stress response in a social context, identifying both changes in an individual’s perceptions of self and others and the organisational factors that cause this individual response. Drawing on this classic approach, we will examine the consequences rather than the causes of burnout, focusing on its interpersonal and social dimensions. To do so, Hartmut Rosa’s postmodern theory of resonance [13] will serve as a theoretical framework. Rosa locates the causes of occupational burnout not only in organisational factors, but also in the breakdown of the individual’s meaningful, enriching relationships with the world (especially those related to the basic axes of resonance, i.e., work and family). The world is understood here as everything that is or can be encountered, as a metaphor for the whole experience [13, p. 34]. Rosa asserts that a person suffering from burnout experiences the world, and consequently their own self, as empty or silent, feeling disconnected, incapable of resonant, meaningful relationships. In this sense, Rosa conceptualises burnout as a crisis of exhaustion in the game of escalation, while pointing out that the ways in which people relate to the world are in most cases shaped and predetermined by social conditions. For him, modernity can be characterised in terms of the expansion of humanity’s share of the world – unfettered progress and opportunity. In the course of this escalation, subjects’ relations to the world – to other people, to nature, to history, to their own bodies and biographies – become silent and produce increasing alienation [13].

While most of the literature focuses on the determinants of burnout, our analysis concentrates on its consequences. In this article, we explore the multidimensionality and complexity of the consequences of burnout by considering not only the individual but also the interpersonal and social dimensions of occupational burnout. More specifically, we explore the ways in which burnout affects the relationships between therapists and their patients, work colleagues, and the workplace.

METHODS

Sampling and data collection

The research sample consisted of alcohol use disorder (AUD) therapists (n = 40) employed in public alcohol treatment facilities who gave written consent to participate in the study. To ensure the diversity of the sample (maximum variation sampling), the selection of respondents took into account the structure of the Polish AUD treatment system in terms of types of facilities (outpatient clinics, day units and inpatient units), size of locality (cities with more or less than 250,000 inhabitants) and length of professional experience (more or less than 10 years) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Number of completed interviews by location, type of facility and therapist work experience

The data were collected in 2021 using the method of in-depth semi-structured telephone interviews, following uniform interview guidelines. The two authors of this paper – sociologists and senior researchers with extensive experience in qualitative research – conducted half of the interviews and carried out the data coding and analysis. The remaining interviews were conducted by two trained psychologists and researchers. All study participants were given information about the project, its purpose, the risks and benefits of participation, and data confidentiality prior to the interview and gave written consent for participation in the study. The function of the interview guidelines was to keep the focus on the subject of the study and to provide a framework to ensure that the data were comparable. We asked the therapists to describe the consequences of occupational burnout on the basis of observations made in their working relationships. Some of them openly referred to and described their own experiences of burnout or its symptoms, others talked about the burnout of their friends and colleagues and their response to it. All interviews were audio- taped and transcribed verbatim, ensuring the removal of any identifying information to maintain anonymity and confidentiality. We did not collect socio-demographic data for reasons of confidentiality.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using ATLAS.ti (CAQDA, Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis). ATLAS.ti allows for a flexible and interpretative approach to interview data. Verbatim transcriptions of the interviews were analysed line by line and coded using keywords related to the themes of the interview [14]. Equal attention was given to each data item and data extracts were coded inductively to capture the essence of each data extract without unnecessary complexity. The next step was to analyse the data using a method of thematic analysis in which some codes were combined to form an overarching theme and others were refined or separated [14, 15].

To obtain meaningful themes in relation to the consequences of professional burnout, personal accounts from AUD therapists were organised and grouped using a realist, semantic approach. In order to move from description to data interpretation and to theorise about the meaning and implications of the data collected, AUD therapists’ differing views of burnout and its consequences were interpreted through the lens of Rosa’s resonance theory as muted, non-resonant relations of the individual experiencing occupational burnout.

RESULTS

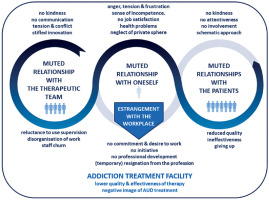

Rosa argues that work is the primary mode through which humans relate to the world [13], making it one of the main axes of his theory. Using this theoretical approach, we categorised addiction therapists’ work relationships into four main domains: the workplace, work colleagues, patients, and the professional self. Consequently, the interrelated consequences of professional burnout identified in this study were theoretically divided into four major groups (Figure I), representing four domains of muted relationships with the world [13].

Figure I

Four interrelated domains of occupational burnout, conceptualised as muted relationships with self, patients, team and workplace, with sub-themes related to specific burnout consequences

The quotations presented in the results section have been anonymised according to the type of therapist training (SUD psychotherapist or SUD assistant therapist) and years of experience (more or less than 10 years), the type of treatment programme (outpatient, day, inpatient), the location of the institution (city over 250,000 inhabitants, smaller city, town, village) and the number of interview (1-40). Although rich qualitative data were collected in this study, we have chosen only one quotation to illustrate the sub-themes that emerged from the data.

Consequences of muted therapist–patient relationships

Our data show that the experience of burnout brings out a range of negative emotions – resentment, anger, frustration or resignation – which distort the therapeutic relationship between patient and therapist. In the silent, non-authentic relationship, the patient may experience a lack of kindness on the part of the therapist, a lack of attention to them and their problems, and a general lack of commitment.

Lack of authenticity

T: Working in a therapeutic community is working on emotions. [In a burnout situation] it lost quality because I withdrew emotionally. I tried not to be involved in the work and that affected my authenticity. I became a theoretical therapist rather than an authentic therapist. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience; inpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 29)

Lack of involvement

T: In this work, it is necessary to be with the patient, to be involved, to be active in the relationship, occupational burnout greatly reduces this activity, [it dampens] thinking about how to help effectively, being vigilant in the relationship. The patient may feel that the therapist is a bit absent-minded, unprepared for the session, forgetting things that have already been said and repeating questions. There is then a lack of attentiveness in contact with the patient. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; inpatient programme; large city; interview no. 10)

The therapist ceases to seek therapeutic interventions that are adequate to the life situation and needs of the patient in question, leading to a schematisation of the therapeutic process and a situation in which the patient-therapist relationship is muted.

Schematic approach, lack of individualisation of intervention

T: We harm patients. If you burn out professionally and do things because you have to, you are not helping. You can repeat standard therapeutic phrases that you know by heart, but it is no longer the case that you treat the patient individually, that each person has a different story and a different addiction. You don’t treat the patient individually anymore, you lump them together, if they are addicted to alcohol, then you [follow] the alcohol [treatment] pattern. (SUD assistant therapist, inpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 20)

As a consequence, patients receive therapy of a lower quality or intensity, i.e., support or counselling rather than in-depth psychotherapy. Therapists have pointed out that in some cases, therapy with a burned-out therapist can be completely ineffective, which reduces the overall effectiveness of therapeutic interventions and can also reinforce the patient’s feeling that therapy is not working in their case.

Reduced quality of therapy

T: The help is not optimal, it becomes either support or counselling, it is not psychotherapy. But our patients sometimes really need deep psychotherapy to deal with their problems. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; day programme; small town/ village; interview no. 19)

Ineffectiveness of therapy

T: The therapist is less involved, the therapy turns into a chat, it can become ineffective. (...) This can encourage patients to drop out [of therapy] or to continue [in therapy] without changing their addictive behaviour. (SUD assistant therapist, outpatient programme; large city; interview no. 37)

Patients sense that the therapeutic relationship is non- resonant, inauthentic, and that the therapist is not attentive or engaged – some of them then report the need for a change of therapist, requesting more adequate, higher quality therapy adapted to their needs. However, there are also some patients who, rather than fight for themselves, drop out from therapy.

Change of therapist

T: I am thinking of a specific situation where the rigidity of what I consider to be a burned-out therapist caused a revolt on the ward, anger from the community, drawing attention to the fact that we are being treated by someone who needs support himself. I heard this from patients and thought maybe they were right. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience; day programme; small town/village; interview no. 24)

Dropping out of therapy

T: Probably some [patients] will leave. (...) A frustrated therapist is a frustrated patient. (...) I think they will drop out of therapy. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; outpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 01)

Consequences of a muted relationship with the team

Occupational burnout not only affects patients, but it also changes the quality of the relationship with other members of the therapeutic team. A muted relationship with the therapeutic team can be illustrated by the inhibition of innovation in terms of the therapeutic programme, the therapeutic interventions used, new ideas or the incorporation of new information or techniques learned from training sessions attended by team members.

Stifled innovation

T: We used to introduce a lot of new ideas to liven up the activities, games to integrate all the senses. At the moment we have almost given that up and I think the patients are suffering as a result. We don’t try as hard as we used to. We used to develop individual tasks for the patients, we tried very hard to respond to their needs, and now it’s all schematic. We as therapists are part of a kind of ossified way of working in the centre, there is no implementation of new ideas, [even if] we go for training, we don’t necessarily use these [new] skills. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; day programme; large city; interview no. 33)

Another indicator of a non-resonant relationship in the team is diminished openness and mutual trust in the team, which manifests itself in resistance to using group supervision (which is a potential tool for dealing constructively with burnout and conflict situations).

Resistance to using supervision

T: Burnout causes irritability in therapists, resistance to receiving information about the quality of their work. I think a lot of defence mechanisms are triggered and this can affect the lack of direct communication within the team and the withdrawal of individuals. I think it leads to less willingness, courage and readiness to discuss one’s own processes with other therapists. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience; inpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 29)

The therapeutic team in a sense ceases to be a team; it is no longer integrated, there is less mutual kindness and support in difficult situations, and there are distortions in communication, often leading to tension and conflict.

Distorted communication

T: [Reflects] People who are burned out are either negative or you can’t rely on them too much. It’s not like we sit down, talk, decide, say yes or no – such a person is indecisive, a bit absent and it disorganises our work. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; outpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 16)

Stress and conflict

T: Burnout causes frustration and from frustration it is not far to anger. Then there is aggression, so there are conflicts that are not directly caused by burnout, but if you think about it, they are a consequence of burnout. (...) A person’s professional burnout can cause conflicts like this. (SUD assistant therapist, outpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 21)

The quality and efficiency of the whole therapeutic team can be affected by lack of resonance and disintegration within the team.

Reduced quality and effectiveness of therapeutic work

T: Professional burnout is related to the quality of teamwork (...). It is difficult when one of the therapists, when talking about patients, has less insight, is less committed, does not draw conclusions that could help the whole team. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience, inpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 08)

T: The effectiveness of the employee’s work, and therefore of the whole team, decreases with burnout. (...) Even if one person is burned out, it affects the others, takes away the commitment and excitement of the work. (...) In this way it can affect the whole team. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience; outpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 17)

Consequences of a muted relationship with the workplace

All of the issues described above regarding the consequences of burnout for the therapist, the patient and the therapy team mean lower quality and effectiveness throughout the organisation. Another consequence of burnout is sickness absence, which further disintegrates the therapy team. Furthermore, all of this can lead to the resignation of not only the burned-out therapist, but also other team members affected by non-resonant team relationships.

Work disorganisation due to absenteeism

T: As a consequence of burnout, the therapist may be absent from work – trying to save himself, he may disrupt the work of the whole centre. It is well known that when there is a heavy workload and someone is absent, there is more work to distribute, it is necessary to cover for someone. This puts a burden on others. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; inpatient programme; large city; interview no. 10)

Staff turnover

T: In a team, I know there is a division between those who are burned out and those who still want to work. Those who still want to work, who are in good shape, fall out of the system. So, the pull in the system is downwards, not upwards; the system adapts to those who are burned out and there is a lower quality of work together with mutual discouragement. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience, day programme; small town/village; interview no. 19)

This affects the perception of the institution, not only in the treatment environment but also among people who may need help. As a result, the number of people seeking treatment in the region may decrease, and the negative social image of addiction treatment may prove to be another barrier to seeking it.

A negative image of the institution/treatment

T: The image of the institution and the services offered are declining. Patients have their opinions, they have their feelings... “I am not satisfied with the therapy with this therapist” (...). When such opinions accumulate, there are many of them, (...) it affects the image of the services in the centre and consequently the willingness to participate in treatment. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience; outpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 11)

Collapse of axes of resonance constituting the subjects themselves

For Rosa, relating to oneself cannot be separated from relating to the world: Subjects do not stand opposite the world, but are always already in a world with which they are interconnected and interwoven [13, p. 32]. In this sense, burnout distorts the relationship with the professional self. The state of occupational burnout is associated with a range of difficult emotions. Therapists have reported extreme tension, suppressed anger and a sense of frustration that leads to resentment towards patients.

Anger, tension and frustration

T: The loss of basic therapeutic skills – the ability to empathise with the patient, the difficulty in forming a bond with them. I think of all the emotions a therapist comes to work with, with anger, resentment... (...) In this profession, you need both willingness and openness to another person. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience; inpatient programme; large city; interview no. 03)

These emotional states translate into a sense of bitterness, a lack of hope and meaning in providing therapy, and gradually lead to avoidance, resignation or a growing sense of incompetence in therapeutic work.

A sense of incompetence

T: Critical self-assessment, I don’t think I am a good enough therapist, and it is personally difficult to think well enough of myself. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience, outpatient programme; large city; interview no. 31)

This inevitably leads to a growing lack of job satisfaction and a decline in the quality of therapeutic work. When talking about occupational burnout, many therapists emphasised that it manifests itself in a reluctance to go to work and to be in contact with patients.

Alienation from work

T: There is a tendency to avoid, I would like to avoid individual therapy or being on the ward. When it happens that a patient doesn’t come, I feel relief (...) A feeling of unfulfilled, dissatisfaction, frustration. (...) What else? Tiredness. (...) I have no satisfaction with my work as a therapist. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; outpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 15)

The accumulation of negative emotions, the reluctance to come to work and to have contact with the patient, results in apathy, passivity, lack of commitment to the therapeutic work, failure to initiate changes, to try out new strategies or approaches, and a lack of initiative to take action to change this difficult situation. At the same time, the desire to develop professionally, to learn new things, to follow trends, to increase one’s competences (despite the feeling that they are insufficient) disappears.

Lack of desire for professional development

T: Being closed to change, there is progress in every field, there are new techniques, methods (...). There is no curiosity in him, he works with a set that he is familiar with, the one that costs him the least. He has no desire to expand his repertoire of techniques, methods, skills - what for, he thinks to himself? (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; inpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 07)

In addition, participants in the study pointed out that professional burnout can also affect the therapist’s private life, among other things because of an overwhelming feeling of being overworked. As a result, a physical relationship with oneself becomes muted. Therapists reported a range of health problems as a consequence of burnout: from somatic health to emotional problems and mental disorders.

Health problems

T: Recently I became depressed and started treatment, and this is also related to burnout. (...) I think my high expectations of myself contributed a lot. I had my first symptoms of burnout after about 10 years of work, I started to find it difficult to accept patients, and when a patient came in, I was irritated that someone wanted something from me. (...) I knew that something strange was going on, because I loved my work, I knew that it was not as usual. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; outpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 12)

The resulting inability to resonate permeates every area of life: Another consequence of professional burnout is the neglect of family and friendship relationships and activities outside work. Moreover, a cause-and-effect chain forms a loop, because maintaining a work-life balance is one of the elements needed to counteract burnout.

Neglecting relationships and non-work activities

T: For me, it showed in the fact that I had to force myself to go to work. (...) I also wasn’t able to manage and use my free time at home, I was more tired, I wasn’t motivated to pursue my passions - swimming and cycling are my hobbies – all that started to get pushed aside. I felt that my mood was dropping significantly. (...) I had difficulty concentrating, (...) it was all exhausting for me. (SUD psychotherapist with less than 10 years’ experience; inpatient programme; small town/village; interview no. 29)

The therapists we interviewed indicated that experiences of burnout have sometimes led (for them or their colleagues) to a temporary resignation from therapeutic work or even to a complete change of profession.

(Temporary) resignation from the profession

T: It can be less productive, it can go into psychosomatic, I had burnout and it was bad enough that I left my job. That was after 15 years of work. (...) 3-4 years later there was this thought that I would like to go back to addictions. (...) Now I know that it was the best decision in my life, that I left my job, I distanced myself for a few years – now I work with a completely different energy. (SUD psychotherapist with more than 10 years’ experience; day programme; small town/village; interview no. 26)

DISCUSSION

The main aim of the work presented here was to provide theoretical insights into the multidimensionality of the consequences of occupational burnout at the individual, interpersonal and social levels. The study – using Rosa’s theory of resonance [13] as a theoretical framework – distinguished interrelated groups of consequences of occupational burnout, conceptualised as muted relationships with the addiction therapist, their patients, the therapeutic team and the addiction treatment facility.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The qualitative design of this study is consistent with our aim to report on the complexity of the consequences of burnout, but it also has some limitations. Although the participants were selected in order to obtain a maximum variation sample, the selection process was purposive, and the results cannot be generalised to all Polish treatment programmes. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first theory-driven study based on Rosa’s theory of resonance [13] to examine experiences and perceptions of the consequences of burnout and provide a higher degree of transferable information than previous qualitative studies in this area.

COMPARISONS WITH LITERATURE

Occupational burnout leads to a schematic approach to the delivery of therapy, manifested by a failure to adapt therapeutic interventions to the patient’s life situation and needs. Patients feel disturbed in their relationship with the therapist, perceiving a lack of commitment, authenticity and attention to them and their problems. As a result, patients receive therapy of lower quality or intensity – some will seek another therapist, others will drop out of therapy altogether. These findings are consistent with other studies showing damage to the therapeutic alliance [9, 11, 16].

Therapist burnout is associated with many difficult emotions that lead to resentment towards patients, passivity and lack of commitment to the therapeutic work, and lack of initiative to take steps that would restore the resonance of the relationship. This leads to a growing sense of incompetence and an awareness of the poor quality of the work being done, similar to the findings of Oyefeso and colleagues [4]. At the same time, and paradoxically, the desire to develop professionally, to learn new things, to increase one’s competences, disappears. As Rosa says, at some point we experience self-efficacy not as a dialogic attainment, but primarily as a control and management technique [13, p. 430], as a result of which any attempt to increase it leads to more alienation.

The results of the study show how an incapacity for resonance in one life domain at some point affects every area of life: Therapists indicated that experiences of occupational burnout were associated with somatic or emotional problems, had a negative impact on their private lives, and led to neglect of both family and friendship relationships and extra-professional activities. Overall quality of life is affected [6, 7]. This chain of cause and effect forms a loop that in some cases can only be broken by temporarily giving up therapeutic work or even by a complete change of profession. What we observe here is an immunisation of everyday action, dominated by the imperatives of optimisation, against one’s own strong evaluations and notions of justice – therapists know how important it is to take care of the private sphere and work-life balance in their professional work, how important professional development and supervision are; at the same time, however, they become entangled in their work, which gradually leaves less and less space for the things that are most important to them.

Team dynamics can play an important role in promoting both resilience and burnout [17]. The effects of professional burnout spill over to the other members of the therapeutic team: it manifests itself in inhibited innovation and reduced levels of mutual trust, openness and support within the team. It leads to resistance to the use of supervision and to disruptions in communication, and tension and conflict. Staff absenteeism or resignations further disintegrate the team, exacerbating chaos in treatment facilities that are often already unstable and underfunded [18]. These factors have also been identified in other research [8-10, 19]. All of these issues lead to a lower quality and effectiveness of treatment across the facility and, consequently, a negative image of the institution, not only in the therapeutic environment but also among those potentially in need of help. This may reduce the number of referrals for treatment, as the negative public perception of addiction treatment becomes another barrier to seeking professional help.

CONCLUSIONS

The complexity of the individual experience of professional burnout and a chain of cause and effect form a loop that deepens the severity and multidimensionality of its consequences. The social dimensions of burnout suggest that the alienated therapist experiences his or her professional and private world as muted. At the same time, addiction patients are deprived of a resonant, healing relationship with their therapist, and the therapeutic team loses the resonant relationship with one of its colleagues.

A chain of cause and effect also forms a loop at a systemic level, which operates according to the logic of escalation: efforts to optimise processes, to ensure the efficiency and availability of treatment by managing output – through financing schemes for treatment facilities and increasing the number of patients per day – lead to professional burnout, which negatively affects the whole system. As Rosa says, the logic of escalation has reached psychological, political and planetary limits [13, p. 425], and only action at the macro level can create the conditions for change.