Introduction

As defined by the American Psychiatric Association, depression is a frequent disease, adversely affecting human health and life [1]. It has a negative impact on the well-being, the way of thinking, but also on the behavior of the person suffering from it. More than 350 million people suffer from depression, including 1.5 million people in Poland. Depression most often strikes in people aged 20 to 40, and affects women twice as frequently as men. It is classified into mental disorders and accompanied by various clinical symptoms, such as: neurovegetative disorders (eating and sleep disorders, lack of energy, weakened concentration), behavioral disorders (anhedonia, i.e. reduced ability to experience happiness and pleasure due to the activities previously perceived as pleasant, e.g. the sense of no meaning in life and inability to function in a society), affective and cognitive disorders (the so-called depressive mood, a sense of worthlessness and hopelessness, suicidal thoughts, an excessive sense of guilt) [2].

As reported by Beurel [3], the development of depression may be fostered by various genetic, biochemical, social, biological and mental factors. In nosological classification of depression in terms of causes, it is possible to enumerate endogenous, psychological and somatic causes. However, the above classification fails to consider a holistic approach to seeking the causes of depression – the classification should be comprehensive in nature and take account of the complexity of the causes. In the opinion of McQuaid et al. [1], multi-origin conditions behind depressive disorders show both their somatogenic and psychogenic structure, including property losses, losses of the loved ones, deterioration of family bonds, loneliness, financial hardships, social isolation, a sense of danger to the present situation and to life, passivity and lack of activities. As stressed by Gunning et al. [4], the disease lasting many years, with periods of remission and acute episodes, has an adverse effect on the health and the quality of life of the sick person.

Pharmacological and psychotherapeutic impact plays an important role in the therapy of depressive disorders. However, the highest amount of evidence from randomized studies confirms the effectiveness of cognitive and behavioral therapy, the essence of which is the cooperation between a psychotherapist and a patient [4].

There is also evidence suggesting that a vital role in the prevention of depressive disorders, based on approved and traditional treatment methods, may also be played by other forms of impact, perceived as factors fostering the treatment [4]. In the opinion of Pederson [5]. such factors include physical activity, defined as any form of movement stemming from the contraction of skeletal muscles, where the energy input exceeds the energy at rest. Based on the available studies, conducted by Kim et al. [6], it may be concluded that physical activity is effective when treating depression, and the result of regular training is comparable to psychotherapeutic intervention.

Aim of the work

The aim of this paper was to present the impact of regular physical activity on the improvement in emotional intelligence in the treatment of depressive disorders.

Methods

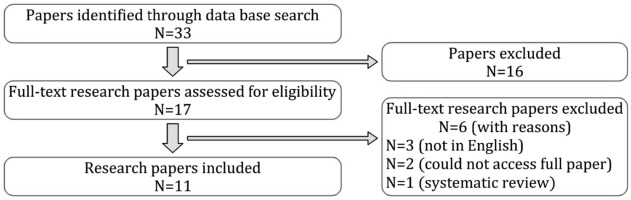

The paper is a narrative review, written based on the documentation analysis method, using the quantitative and the qualitative technique. The tool used was the Polish and the international scientific literature from databases, i.e. Web of Science, PubMed, Google Scholar, Europe PMC.

The article presents the results of studies included in international publications from the period of 2017 to 2023, concerning the impact of physical activity on the improvement in mental health, co-dependent on emotional intelligence. The author conducted a detailed analysis of articles, taking account of the type of the therapeutic impact and the documented effects of the therapy.

From the aforementioned databases, 31 articles in English were selected, concerning the issues of the impact of physical activity on supporting emotional intelligence in the treatment of depressive disorders. Eleven papers were chosen for more thorough analysis, as they met high methodological requirements, as well as the following inclusion criteria:

They presented a complex neurophysiological background behind depression.

They presented various forms of physical activity, influencing an improvement in mental health, in connection with emotional intelligence.

They took account of the assessment of treatment progress after various doses of physical activity in depressive disorders.

The analysis did not cover papers not related directly to the topic, written in languages other than English, abstracts containing no data and systematic reviews. The following keywords were used for the search: emotional intelligence, depression, physical activity, sports, training. The search strategy results are presented in Figure 1.

Literature review results

Relation between emotional intelligence and depression

The studies aimed at finding the factors determining the quality of human life focus mainly on the personality traits of an individual, and on cognitive skills.

In recent years, scientists have been demonstrating a broader understanding of intelligence, which is proven by further characteristics and categories included in the definition of intelligence. Such a view is substantiated by the emotional intelligence concepts, aiming at finding new ways to answer the questions about the relations between intelligence and professional or life successes [7]. The literature of reference discusses alternative models of emotional intelligence. The best known ones are: popular models by Goleman [8] and Bar-On [9], as well as the scientific model by Salovey and Mayer [10]. The concepts formulated by Goleman [8] and Bar-On [9] are called mixed models, because the notion of emotional intelligence is supplemented with other, mainly motivational characteristics, not being skills. Goleman [8] claims that emotional intelligence is a different type of wisdom, consisting of: self-motivation, knowledge of one’s emotions, control of emotions, maintenance of relationships, recognizing emotions of others. Bar-On [9], on the other hand, defines emotional intelligence as a series of non-cognitive skills, abilities and competences, allowing an individual to effectively cope with the external pressure and requirements. Based on the query and the analysis of psychological literature, with regard to personality traits typical of successful people, the author enumerated five areas of functioning: 1) intrapersonal skills, 2) interpersonal skills, 3) adaptation skills, 4) coping with stress, 5) general mood. The concept put forth by Salovey and Mayer [10] is a skill-based model, as it assumes that emotional intelligence is a set of human cognitive skills.

As reported by O’Conor [11], emotional intelligence is an important factor influencing the quality of life. It makes it possible to recognize emotional states and, at the same time, control them in a manner enabling management and adjustment of one’s own and other people’s behaviors, depending on the given situation. According to Mo et al. [12], recognition of facial emotional expressions is one of the elements of social cognition, and a determinant of emotional intelligence. The ability to control one’s own emotions and the resulting behaviors strongly affects the quality of interpersonal relations. Facial expressions are a constituent element of non-verbal communication, and the correct interpretation of such information proves to be a necessary condition to maintain proper relations with other people. In the opinion of Samios et al. [13], adequate emotional reaction affects the ability to use proper cognitive strategies, as well as strategies of coping in difficult situations. These strategies, in turn, reduce the risk of negative mental effects. Studies by Wang et al. [14] suggest that people diagnosed with depression show certain lacks in the scope of ability to process emotional stimuli. It was demonstrated that people suffering from depression are less likely to recognize emotions based on facial expressions than people not affected by the said disease. Studies by Simcock et al. [15] prove that the ability to correctly recognize one’s own emotional states conditioned protection during stressful life events and reduced the risk of depression development. In the opinion of Baghcheghi and Koohestani [16], people with a lower emotional intelligence index are more likely to apply immature defense mechanism and demonstrate more difficulties in controlling their emotions, a lower empathy index, higher scores in anxiety scales, and suffer from mental disorders more frequently.

Depression-related morphological changes in the brain, in connection to emotional intelligence

Neuropsychological bases for deficits in social cognition in depression are still not known to the full extent. Studies in the field of cognitive psychology, neuropsychology and neuroimaging demonstrated defects in the structures of nerve cells, related, among others, with a change in the degree and the length of dendrite branching and the decaying thickness of dendritic spines [17]. Abundant evidence shows that stress slows down the signaling of neural reconstruction processes, related to the production and the functioning of the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which, as a consequence, weakens the structural plasticity of the brain [18].

Moreover, patients with depression demonstrated an effect in the form of reduced volume of the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus. The aforementioned structures are considered important from the viewpoint of pathogenesis of depression. The hippocampus plays an important role in the transmission of information from short-term to long-term memory, and in spatial orientation. The prefrontal cortex, on the other hand, inhibits spontaneous, often violent emotional reactions [18].

Certain premises also indicate that long-lasting, intensified release of cortisol, in response to the stress experienced, may cause permanent neural damage of the hippocampus, in the scope of structures responsible for the functioning of the feedback mechanism, controlling the hypothalamus-hypophysis-adrenal glands axis. Excessive activation of this axis leads to disorders in cognitive processes and to intensification of the symptoms of depression [18].

Studies employing magnetic resonance imaging proved the existence of a positive correlation between emotional intelligence and the thickness and the volume of grey matter in areas responsible for responses involving non-verbal understanding of emotions and the ability to interpret them based on body language. Thus, it could be concluded that changes in the scope of emotional intelligence in depression are related to the reduced ability to control and recognize emotions, i.e. the processes related to the functioning of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex [19].

Analysis of the results of studies on the impact of physical activity on the support for emotional intelligence in the treatment of depressive disorders

A thorough analysis was conducted of studies concerning the impact of physical activity on the support for emotional intelligence in the treatment of depressive disorders, taking into account the number of respondents in each group, the type of physical activity, the duration of the therapy and its documented effects. The analyzed variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

List of the analyzed results of studies on the relation between physical activity and emotional intelligence in depressive disorders

| Author | Study elements | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Park et al. [20] | Studied group | 3647 people (men = 1380 and women = 1267) |

| Method | KYPS (Korea Youth Panel Survey) scale | |

| Duration | 2003 to 2008 | |

| Physical activity type | football, basketball, bodybuilding, boxing and tennis | |

| Results | Studies demonstrated that regular training is a factor protecting people from neural and behavioral disorders. | |

| Smail- Crevier et al. [21] | Studied group | 1011 people (men = 511 and women = 500), aged 18 |

| Method | Canadian Internet Use Survey conducted by Statistics Canada | |

| Duration | 9 months, March to December, 2015 | |

| Physical activity type | e-mental health programmes | |

| Results | The studies demonstrated that women, more often than men, turned to exercises helping them reduce the symptoms of stress and depression. | |

| Singh et al. [22] | Studied group | 150 women (75 athletes and 75 non-athletes), aged 19 to 26 |

| Method | Emotional Intelligence Scale | |

| Duration | no data | |

| Physical activity type | athletics | |

| Results | It was observed that women with higher levels of emotional intelligence were more likely to use adaptive self-regulation techniques, such as: internal monologues, imagining strategies, relaxation techniques or altruistic behaviors. | |

| Patria [23] | Studied group | 12 051 people (men = 6340 and women = 5711), aged 18 to 65 |

| Method | IFLS (Indonesian Family Life Survey) | |

| Duration | 1993, 1998, 2000, 2007, 2014 – 2015 | |

| Physical activity type | weight lifting, cycling, aerobics | |

| Results | The studies provided evidence that regular physical activity has a beneficial effect on the sense of self-sufficiency and increased self-esteem. | |

| Author | Study elements | Description |

| Castro- Sánchez et al. [24] | Studied group | 372 (men= 235 and women = 137) aged 18 to 50 The criterion for the breakdown was the sports discipline practiced. Among the respondents: a) 46.2% of the people played individual contact sports, b) 37.9% played individual non-contact sports, c) 11.1% played team non-contact sports, d) 4.8% played team contact sports. |

| Method | Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire (PMCSQ-2), Schutte Self Report Inventory (SSRI). | |

| Duration | 4 months, September to December, 2016 | |

| Physical activity type | tennis, football, taekwondo, running | |

| Results | The conducted studies demonstrated lower intensity of stress and depressive symptoms in the group of people playing team sports. | |

| Luttenberger et al. [25] | Studied group | 156 people, aged 26 to 44 79 people were assigned to the bouldering psychotherapy BPT group, and 77 to the cognitive behavioral group therapy CBT, at random. |

| Method | Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Patient Health questionnaire (PHQ-9) | |

| Duration | March, 2017 to March, 2018 | |

| Physical activity type | bouldering | |

| Results | Based on the conducted studies it was demonstrated that the intensity of depressive symptoms decreased, on average, by one degree in both groups. An improvement in interpersonal sensitivity and self-esteem was also observed. | |

| Gorham et al. [18] | Studied group | 4191 children, aged 9 to 11 |

| Method | magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Duration | no data | |

| Physical activity type | basketball, field hockey, football, ice hockey, rugby, football or volleyball | |

| Results | The study results showed that doing sports correlated positively with the volume of the hippocampus, which is of crucial importance for mental health improvement. | |

| Skurvydas et al. [26] | Studied group | 6369 respondents (men = 1824 and women = 4545), aged 18 to 74 |

| Method | The 10-item perceived stress scale (PSS-10), Schutte self-report emotional intelligence test (SSREIT) | |

| Duration | October, 2019 to June, 2020 | |

| Physical activity type | Danish Physical Activity Questionnaire (DPAQ) | |

| Results | The studies demonstrated higher emotional intelligence levels among women, while men showed less depression symptoms. The perceived stress level was higher in adults aged 18 to 24, compared to adults aged 45 to 54. | |

| Acebes- Sanchez et al. [7] | Studied group | 2960 people (men = 973 and women = 1987) aged 17 to 26 |

| Method | Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS) | |

| Duration | April to December, 2017 | |

| Physical activity type | Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). Three areas of physical activity were assessed: a) occupational physical activity (OPA), b) commuting physical activity (CPA), c) leisure time physical activity (LTPA). | |

| Results | Studies demonstrated that the physical activity level differed depending on the gender. Men achieved higher scores in LTPA and OPA areas. Also, differences regarding emotional intelligence, depending on the gender, were demonstrated, with higher results in the scope of emotional attention and emotional clarity among women, and higher emotional repair level among men. | |

| Campos- Uscanga et al. [27] | Studied group | 331 people (men = 148 and women = 183) aged 18 to 80 |

| Method | Brief Emotional Intelligence Inventory (EQ-i-M20), Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ), Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale | |

| Duration | April 1st to April 30th, 2021 | |

| Physical activity type | running in natural areas | |

| Results | It was observed that men tended to go running in natural areas more frequently (66.2%) than women (55.2%). Moreover, men demonstrated better mental well- being than women. | |

| Rodriguez- Ayllon et al. [28] | Studied group | 124 pregnant women (12th week of pregnancy) |

| Method | Depression Scale (CES-D), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T), Trait Meta- Mood Scale (TMMS) | |

| Duration | November, 2015 to March, 2017 | |

| Physical activity type | physical fitness tests: back-scratch test, handgrip test, 6-min walk test | |

| Results | The studies demonstrated that moderate physical activity influences the reduction in depressive symptoms and fosters emotional regulation. |

Conclusions

Over the recent 5 years, many papers have been published, discussing the relations between physical activity and emotional intelligence in depressive disorders. As implied by these studies, it is hard to separate emotions from cognitive processes in everyday life, as most experiences activate the cognitive processes, and emotions are an inseparable element of cognition. It is a well-established fact that our emotional state triggers the related memory resources. Memories are easiest to recall, when our current emotional state matches the state from the time when these memories were formed. The compliance principle concerns not only memory processes, but also attention, linguistic skills or perception [29].

The studies by Yoou-Jong et al. [30] confirm the theory about the existence of two aspects of emotional intelligence – the stable aspect, not changing depending on the ability to understand current emotional state, and the aspect reflecting the current emotional state of an individual, e.g. the ability to see the subtle differences between emotions and to interpret their meaning. In other words, it can be stated that there are both constant and variable aspects of emotional intelligence. In the opinion of the author, these aspects are personality traits predisposing the development of depressive disorders. Spellman and Liston [31] suggest that operational memory and cognitive functions play the decisive role in conscious emotional regulation. It also turns out that higher effectiveness of operational memory fosters positive self-reinforcement and resistance to external negative feedback.

Based on the analysis of the literature of reference, it is possible to observe a strong correlation between physical activity and better mental state, both in the cognitive and the emotional aspect. An equally important issue are positive social interactions and the opportunity to participate in physical recreation and sports competitions. The study results quoted above prove that physical activity, regardless of the age and the gender of the respondents, can be used to support emotional intelligence in the treatment of depressive disorders, in children, teenagers and adults. It was demonstrated in the studies, irrespectively of the number of respondents in the studied groups, which varied, depending on the organizational capabilities of particular studies. The smallest group included 124, and the largest – 12051 people.

Numerous premises of various nature indicate a rise in cases of depression in the years to come (or in the future). This calls for measures counteracting this detrimental phenomenon. Evidence shows that rationally dosed physical activity, related to emotional intelligence, may play a vital role in prevention and support of treatment of this disease, so widespread nowadays [32]. As shown by the conducted analysis, positive results were achieved regardless of the assumed (or applied) form of physical activity. It seems that regularity of such activity should be the condition for long-lasting effects.

In the light of available data presented in the article, it can be concluded that there is a need for more thorough analyses are needed and, in the long run, for optimum preventive and therapeutic strategies, employing broadly understood physical activity in the discussed scope.