Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most common causes of disability and death worldwide [1,2]. As of 2017, 425 million people worldwide had diabetes, with a projected 629 million cases by 2045 [3]. The global prevalence of diabetes is estimated at 10.5% of the world’s adult population [4]. Currently, the prevalence of diabetes is higher in urban than in rural areas (12.1% vs. 8.3%) and in high-income countries (11.1% vs 5.5% in low-income countries) [4]. It is estimated that global diabetes-related health expenditures will increase from 966 billion USD in 2021 to 1,054 billion USD in 2045 [4]. Except for the health consequences of diabetes and its complications, diabetes has a significant social impact [5,6]. Diabetes is associated with a significant risk of disability [5]. Moreover, it is estimated that diabetes reduces productivity-adjusted life years (PALYs) by 10-12% [6].

To reduce the health and economic burden of diabetes, numerous countries have implemented health policies and management programs on diabetes [7-9]. Type 1 diabetes-related health policy programs (HPPs) are focused on secondary prevention, including early detection of diabetes and effective disease management strategies [10,11]. Type 2 diabetes-related HPPs offer primary and secondary prevention strategies [8,9,12]. Primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mostly focuses on education on risk factors and their modification [9,12].

Overweight and obesity are the most important risk factors for developing prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in adults [13]. Other risk factors include dietary and lifestyle factors, older age, genetic predisposition (family history of diabetes), history of gestational diabetes, and history of polycystic ovarian syndrome [13,14]. Dietary habits and lifestyle are modifiable diabetes risk factors and may be targeted by lifestyle change interventions [9,14]. Moreover, screening asymptomatic adults for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes allows earlier detection of this disease [15]. Opportunistic screening is considered effective in the early detection of type 2 diabetes [16]. Early detection of diabetes mitigates the risk of complications and thus improves the quality of life of people with diabetes [16,17].

The prevalence of diabetes in Europe is estimated at 56.5 million cases, of which 24.2 million are undiagnosed [18]. Between 2017 and 2045, the prevalence of diabetes in Europe will increase by 13% [3,4]. In Poland, according to various estimates [3], more than 2 million adults (approximately 8% of the population) have diabetes, most of whom (more than 90%) have type 2 diabetes [19,20]. It is estimated that more than 20% of patients with diabetes in Poland are undiagnosed [19,20].

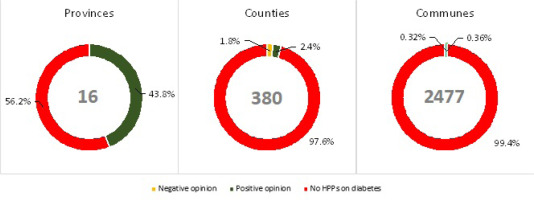

In Poland, there are two major types of health policy and management programs for diabetes. The first type is nationwide HPPs implemented by governmental institutions such as the Ministry of Health, the National Health Fund, or the National Institute of Public Health. These nationwide programs are part of the country’s health strategy and are aimed mostly at the country’s general population [21]. Educating patients with diabetes and their families and carers is one of the main objectives of the National Health Program for 2021-2025 [21]. Except for the national HPPs implemented by the government, the second type of HPPs are those implemented by local government units (LGU) [22,23]. In Poland, LGUs play an important role in providing healthcare services [22,23], including preventing non-communicable diseases. According to legal regulations, HPPs planned by an LGU must be evidence-based and comply with the national health policy defined in the National Health Program [23]. A local government unit that intends to implement a health policy program must submit a draft of this program to the Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System (AHTATS) for an opinion [24,25]. AHTATS is a government unit dealing with health technology assessment (HTA), including issuing opinions on HPPs [24,25]. All LGUs are obliged to obtain the Agency’s opinion on the drafts of their HPP before proceeding unless AHTATS has issued a general recommendation on a given health problem (ready-made program templates, which allow LGUs to save the time needed to wait for an opinion) [25]. Data on planned HPPs are submitted using a dedicated template defined by the AHTATS [25]. The health policy program implemented by the LGU should include a description of the health problem, justification for the program’s introduction supported with epidemiological data, program objectives and measures, target population, detailed characteristics of interventions planned, evaluation methods, and budget [25]. Poland is divided into three types of administrative regions: 16 provinces, 380 counties, and 2477 communes [26]. All the above mentioned administrative regions have local governments that can run HPPs after approval is obtained from AHTATS.

National HPPs on diabetes prevention and control were analyzed in a number of papers [19,20,27,28]. However, little is known about diabetes-related HPPs implemented or planned by local government units in Poland.

Aim of the work

This study aimed to identify, characterize, and evaluate diabetes-related HPPs implemented by Local Government Units (LGUs) in Poland between 2012 and 2022.

Material and methods

Study design and settings

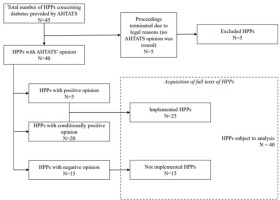

This is a retrospective database analysis of diabetes-related HPPs implemented by LGUs in Poland between 2012 and 2022. Data on HPPs submitted to the AHTATS were collected from the public information bulletin published on the official website of the Agency [29]. All HPPs submitted to the AHTATS by LGUs are published regularly on the website and are available publicly. Diabetes-related HPPs submitted to the Agency between 2012 and 2022 were identified using the following keywords: diabetes (cukrzyca in Polish) and health policy program (program polityki zdrowotnej in Polish). Out of the 1974 HPPs submitted by LGUs between 2012 and 2022, 45 diabetes-related HPPs were identified. Of the selected 45 HPPs filed by LGUs, 5 HPPs received a positive opinion, 20 were rated conditionally positive (may be implemented after revisions), and 15 received a negative rating. In the case of 5 documents, AHTATS assessments were terminated due to legal reasons (mainly the LGU failing to provide a complete application). The data collection process is presented in Figure 1.

Measures

Proposals of HPPs were submitted by LGUs using a dedicated template [25,29]. The following data on HPPs were screened:

title of the program,

type of LGUs (province / county [or city with county rights] / commune),

population size,

description of the health problem in the local community (type 1 diabetes / type 2 diabetes),

program objectives and measures,

target population,

characteristics of the intervention (i.e., health promotion, primary prevention; secondary prevention; tertiary prevention),

expected results,

evaluation methods,

AHTATS’ opinion on the program (positive opinion / conditionally positive opinion / negative opinion).

Only programs with a positive or a conditionally positive (approved after correction) opinion may be implemented by the LGUs. Analysis of full texts of HPPs was conducted independently by two researchers (JGS and KS). The research team collectively resolved any differences in the assessment of documents.

Data analysis

Data on diabetes-related HPPs with positive or conditionally positive recommendations of AHTATS (n=25) were entered into the electronic database (MS Excel, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA). Descriptive statistics were used. Data were analyzed separately for type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes-related health policy programs were assessed using six different categories:

the type of diabetes,

the type of LGU and population size,

program submission year and duration time,

target groups,

the scope of health policy programs implemented by LGUs,

public health interventions planned within the program.

A comparison of the HPPs was presented in tables using proportions and counts.

Results

Diabetes-related HPPs implemented in Poland between 2012 and 2022

Out of 1,974 HPPs submitted by LGUs between 2012 and 2022, only 2.3% (n=45) were diabetes-related HPPs, and 1.3% (n=25) of the HPPs were implemented. All diabetes-related HPPs focused on type 2 diabetes, and there were no programs on type 1 diabetes implemented or planned by LGUs in Poland. Out of 16 provinces in Poland, 43.8% (n=7) had implemented at least one diabetes-related HPP (Table 1). Of 380 counties, 4.2% worked on diabetes-related HPPs (n=16), but only 2.4% (n=9) had implemented such a program. Out of 2477 communes in Poland, fewer than 1% (n=23) worked on diabetes-related HPPs, and only 0.36% (n=9) of communes had implemented at least one HPP on diabetes (Figure 2). The population of LGUs where the diabetes-related health policy programs were implemented varied from 3,094 residents in Świerczów Commune to 5,510,612 residents in Mazowieckie Province (Table 1). The duration of diabetes-related health policy programs varied from 6 to 72 months. Most programs (44%) were scheduled for 36 months (Table 1).

Table 1

Health policy programs implemented by LGUs in Poland between 2012 and 2022

Characteristics of diabetes-related HPPs – target groups

Out of 25 diabetes-related HPPs, 19 (76%) were addressed to more than one target group (Table 2). Most programs were addressed to the general public (n=12; 48%) or to patients (n=13; 52%). Only three programs (12%) were addressed to children. Diabetes patients were listed as the target group in 9 programs (36%). Only one program was addressed to the families of diabetic patients (Table 2).

Table 2

Target groups listed in health policy programs implemented by LGUs in Poland between 2012 and 2022

Characteristics of diabetes-related HPPs – levels of prevention

Most of the diabetes-related HPPs by LGUs in Poland were focused on secondary prevention (n=17; 68%), and 16 programs (64%) were focused on health promotion. Out of 25 programs, 8 (n=32%) were focused on tertiary prevention, while 28% (n=7) were focused on primary prevention of type 2 diabetes (Table 3). Between 2012 and 2022, 6 programs (24%) were concentrated on only one type of intervention (Table 3). Almost half of the programs (n=12; 48%) comprised two types of interventions: health promotion and secondary prevention of type 2 diabetes (Table 3).

Table 3

The scope of health policy programs implemented by LGUs in Poland between 2012 and 2022

Characteristics of public health interventions planned within diabetes–related HPPs

Health education was the most common public health intervention offered within the HPPs (88%). Body Mass Index (BMI) and/or Waist Hip Ratio (WHR) measurements were offered within 14 programs (56%). Within 13 different programs (52%), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and/or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) were offered. Moreover, four programs (16%) included the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test. Blood pressure measurement was provided within nine programs (36%), and in 8 programs (32%), healthy eating advice was offered. Physical examination was provided by five programs (20%), and only two programs (8%) offered a consultation with a diabetologist (Table 4).

Table 4

Public health interventions planned within the HPPs implemented by LGUs in Poland between 2012 and 2022

Discussion

This is the first study to characterize diabetes-related HPPs implemented in Poland. Findings from this study showed that out of all the HPPs proposed by the LGUs, only 2.3% were related to diabetes as a primary objective. Moreover, diabetes-related HPPs that were finally implemented amounted to only 1.3% of all HPPs. All programs were focused on type 2 diabetes. Most of the diabetes-related HPPs were addressed to the general population, and the target population selection was often ineffective. Health promotion combined with secondary prevention were the most common actions planned within diabetes-related HPPs. Health measurements offered within the programs were mostly limited to FPG/OGTT test or BMI/WHR measurement. This study revealed significant gaps in HPPs implemented by LGUs in Poland.

The Polish National Health Program (NHPP) has recognized the prevention of diabetes as a top priority in the national health policy [30]. Through public education, the program aims to increase awareness about the risk factors associated with diabetes and promote healthy lifestyle choices [30]. Early detection and screening for individuals at high risk of diabetes are one of the priorities of the NHPP [30]. However, despite the goals set out by NHPP, local and regional authorities have not fully embraced the implementation of HPPs for diabetes prevention. This is particularly evident in the lowest level of local government units – communes, where the adoption rate is very low. Fewer than 1% of communes have proposed a diabetes-related HPP, and only 0.36% received approval from AHTATS [25]. This observation corresponds with the 2017 report from the Polish Supreme Audit Office, which stated that the implementation of the NHPP lacked sufficient and inclusive participation from local and regional authorities [31]. LGUs in Poland are actively involved in other HPPs, such as programs on cancer prevention, immunization, and cardiovascular diseases [23,31,32].

Several potential explanations exist for the low implementation of diabetes-related HPPsby LGUs in Poland. Policies that promote healthy food choices, such as taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages [33], and encourage physical activity, such as building bike lanes and walking paths [7], have proven to be effective. Still, according to Polish law, those interventions cannot be undertaken by LGUs within the HPPs [25]. A HPP is defined as a set of planned and intended activities in the field of health care assessed as effective, safe and justified, enabling the achievement of assumed goals within a specified period, consisting of detecting and meeting specific health needs and improving the health condition of a specific group of beneficiaries. This excludes many lifestyle- related interventions (those not consisting of actions of detecting and meeting specific health needs), as they do not meet such definition. Therefore, LGUs’ efforts focus on secondary and tertiary prevention rather than health promotion and primary prevention, which could lead to a decrease in the incidence of diabetes.

Findings from this study showed that out of the 45 diabetes-related HPPs analyzed, only five were rated positively by AHTATS, while 20 received a conditional positive assessment. The study by Augustynowicz et al. revealed that LGUs in Poland lack the necessary expertise to design health interventions that comply with legal requirements for HPPs [34]. It is observed that larger local government units with more resources and better staff, including graduates of public health departments, could prepare HPPs that were rated positively by the AHTATS [22]. This may lead to disparities in health policies and health inequalities among inhabitants of different regions.

According to Polish law, AHTATS can issue a general recommendation on a given health problem [35]. Adopting a recommendation on diabetes could encourage LGUs to act on diabetes prevention. Augustynowicz et al. showed that implementing AHTATS guidelines on HPV prevention by LGUs led to an increase in HPPs on HPV carried out by LGUs [36].

There is a consensus that lifestyle-related interventions are cost-effective in reducing the incidence of type 2 diabetes [7,9,10]. In this study, numerous HPPs have focused on health education and secondary prevention. There was a limited emphasis on primary prevention of type 2 diabetes. Further programs should include primary prevention of diabetes as one of the key targets [7,8]. Special attention should be given to lifestyle interventions (e.g., weight loss programs) which are proven to be effective in reducing diabetes risk. Such interventions can be provided by nonmedical personnel, which further increases their cost-effectiveness [37].

This study showed that LGUs targeted their programs to various populations. Most of the programs were targeted at the general public or unspecified groups of patients visiting medical facilities. Communes tended to address their interventions to older adults. This can be explained by the fact that at the local level, it is easier to identify and reach target groups. Larger LGUs, especially provinces, focused on more generically specified target groups or planned their activities to be addressed to the public. Selecting a target population for diabetes prevention programs is necessary to improve the program’s effectiveness [38,39]. LGUs should pay more attention to the selection of target groups for HPPs.

Most proposed interventions involved providing patients with basic medical tests such as blood pressure, BMI, WHR calculations, and some basic laboratory tests for OGTT/FPG levels [40]. The HbA1c tests were less frequent. BMI/WHR measurements and simple laboratory tests (including OGTT, FPG, and HbA1c tests) should be included in the HPPs on diabetes as a basic diagnostic tool [40,41]. As this is the first study on diabetes- related HPPs, direct comparisons with other studies are limited.

Conclusions

This study has practical implications for health policy in Poland. LGUs should improve their actions to plan and implement HPPs [19,20]. Diabetes is a significant health problem in Poland, so LGUs may contribute to reducing its burden, especially in the case of type 2 diabetes. This study also revealed weaknesses of the HPPs submitted by the LGUs to AHTATS. LGUs should better define target populations. Moreover, the minimal duration of the HPPs should be determined at the national level. LGUs should use expertise provided by public health graduates, as well as public health specialists, in designing, implementing and monitoring health policy programs and other activities aiming at diabetes prevention.

Limitations

This analysis was limited to HPPs with diabetes as a primary objective of the program. Programs where diabetes prevention was a secondary objective (e.g., as a part of healthy lifestyle promotion) were not included. Moreover, due to the lack of data, evaluation of the effectiveness of diabetes-related HPPs was not assessed. HPPs on diabetes implemented by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or local healthcare facilities were also not included in the analysis.