PURPOSE

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the anxiety disorders – a chronic, pathological mental reaction to a traumatic event. It is estimated that 7 to 8% of the general population may suffer from PTSD in their lifetime [1, 2]. The risk of this is nearly twice as great for women (10.4%) than it is for men (5%). Sexual abuse is associated with the greatest risk of developing PTSD in women [1]. Although common, PTSD poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges [3, 4], likely associated with co-occurring comorbidities. Over 80% of people suffering from PTSD meet the criteria for at least one more psychiatric condition, especially affective disorders. A major depressive disorder (MDD) accompanies PTSD in almost 50% of patients initially diagnosed with PTSD [1].

First line treatment for PTSD is trauma focused psychotherapy, including eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR) [5-8] whereas electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is one of the most effective treatments for MDD [9, 10]. Some data suggest that in patients with comorbid MDD and PTSD, treatment with ECT leads to an improvement in the symptoms of both disorders [11-17]. Studies on the effectiveness of ECT in patients suffering from PTSD, MDD and anorexia nervosa (AN) at the same time have been few, but they have also given positive results, including an increase in the body mass index (BMI) of the examined patients [18].

Here we present a case report of a patient with the three aforementioned comorbid conditions, treated with three methods simultaneously (pharmacotherapy, ECT, and EMDR). We describe the methods that helped us overcome challenges in treating the patient and present the effect of ECT on each of the three disorders – PTSD, MDD and AN. We also show how the use of ECT may impact the length of hospitalization.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 28-year-old female patient was admitted urgently to the hospital because of suicidal thoughts and tendencies. Upon admission, she reported a depressed mood, auto- aggression, food restriction, and flashbacks that had increased in frequency and intensity over the previous few months. She also suffered from insomnia and recurrent nightmares related to the trauma; these occurred about twice a week. The day of her admission was the anniversary of a traumatic event.

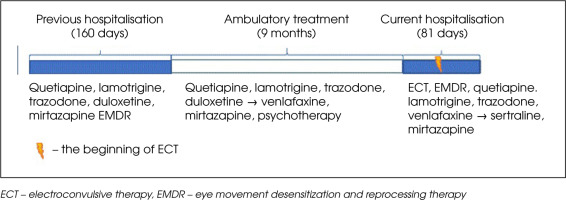

The patient had been treated psychiatrically for the previous ten years and had been diagnosed with the following conditions: recurrent depressive disorder, borderline personality disorder, anorexia nervosa (AN), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). She had experienced a severe trauma (sexual assault) at the age of 17, which led to two suicide attempts by means of drug overdose, the most recent of these having taken place three years before the current admission. She was hospitalized psychiatrically four times – recently at our Psychiatric Department, one year before (Figure I). On that occasion the patient was diagnosed with PTSD for the first time. Hospitalization significantly improved the patient’s well-being. Adhering to the prescribed therapeutic regimen (Figure I), the patient reported feeling well after discharge. She was employed and rented an apartment with her friends. During one of her outpatients visits she linked her mental deterioration with a flashback-triggering factor – the upcoming anniversary of the traumatic event.

The patient’s father suffered from schizophrenia and alcohol abuse disorder. He attempted suicide once but eventually died of a brain tumor. The patient’s brother was aggressive verbally and physically. Her cousin committed suicide. The patient denied using alcohol or other psychoactive substances. She smoked about 1-2 packs of cigarettes a day. Somatic comorbidities included mitral valve prolapse and sinus tachycardia. The patient was treated with metoprolol 50 mg q.d.

On admission the patient was significantly underweight (BMI of 14.7 kg/m2) and confirmed that she had been limiting her food intake because of “feeling fat”. Her body had multiple scars (old and new) resulting from self-harm. The patient was in a state of psychomotor restlessness. Her mood seemed anxious and sad; her affect was restricted. She complained of multiple flashbacks, intense guilt, self-hatred, and a lack of hope. She confirmed suicidal thoughts and tendencies. She denied hallucinations and did not reveal any indicators of delusional thinking.

During her hospitalization the patient received psychotherapy from a psychologist trained in the use of the prolonged exposure protocol during her 4-year training in cognitive behavioral therapy. The prolonged exposure protocol was not applied due to the patient’s severe agitation, associated with talking about traumatic memories. There were significant difficulties in stabilizing the patient and installing resources in a safe place. For this reason, an EMDR protocol adapted for working with complex trauma was used , which allows for working on small fragments of traumatic memories, which is less stressful for patients than working with the entire traumatic memory at once. The patient agreed to this model of work. During hospitalization, the patient attended EMDR sessions once or twice a week, depending on her mental state and her decision. She was treated with quetiapine (max 100 mg/d), lamotrigine (max 200 mg/d), trazodone (max 150 mg/d), venlafaxine (max 375 mg/d) and mirtazapine (max 45 mg/d). Despite increasing the dose of venlafaxine to 375 mg q.d., adding clorazepate, tiapride and chlorprothixene, and continuing psychotherapy, the patient’s mental state failed to improve. She attempted suicide by hanging herself using a headphone cable and was still declaring suicidal tendencies. She was strictly supervised. Due to a long history of insufficient pharmacotherapy and a high risk of suicide, we referred the patient for ECT.

After obtaining the patient’s consent and carrying out the necessary medical examinations, we withdrew the clorazepate and reduced the dose of lamotrigine because both medications may increase the seizure threshold. We decided to use flumazenil before the first ECT to reverse clorazepate’s influence on the excitability of cells. We also reduced the venlafaxine dose to avoid potential cardiotoxicity.

ECT was administered twice a week with the Thymatron System IV. The seizure threshold (ST) was determined using the titration protocol during the first session [19]. We performed 12 courses of brief-pulse ECT (3 bitemporal and 9 unilateral). Because of intense suicidal ideation, we started with bitemporal electrode placement. Due to a quick response and increasing cognitive side effects, electrode placement was changed to unilateral after three successful sessions. The stimulus intensity was selected by multiplying the initial ST ×2.5 for bilateral ECT and ×6 for right unilateral ECT, reaching 126 and 302.4 mC respectively (20.21). Seizure lengths were monitored with electroencephalography (EEG). The seizure was considered adequate if EEG ictal activity lasted at least 25 seconds [19]. Since seizure durations ranged from 31 to 111 seconds, all ECT sessions were considered adequate. The total duration of all seizures was 920 seconds. The pre-ECT medications administered were atropine 0.3-0.5 mg, etomidate 16-20 mg and succinylcholine 50 mg.

The patient was under strict supervision between the time of admission and the first ECT because of suicidal thoughts and tendencies. The strict supervision of her was discontinued two weeks after the first ECT. Following the ECT the patient’s Beck Depression Inventory – II rating score improved by 21 points and PTSD checklist PCL 5 from DSM 5 improved by 8 points (Table 1). CGI was assessed weekly during hospitalization. We saw the first visible change in the CGI score after the 1st ECT (from 7 to 5 scores), then after the 2nd – CGI 4/5; 4th – CGI 3/4; 8th – CGI 4/5; 10th – CGI 4, and 12th – CGI 3 (Table 1).

Table 1

Result summary

| Days of strict supervision | Beck’s depression rating scores | PTSD checklist for DSM scores | CGI-S score | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ECT | 40/40 | 48/63 | 65/80 | 7/7 | 14.7 |

| After ECT | 14/41 | 27/63 | 58/80 | 3/7 | 17.6 |

After completing the course of ECT the patient’s mood seemed close to normal. She stopped presenting auto- aggressive behavior. The symptoms of PTSD were still present, but the patient declared “having more strength to deal with them” (Table 1). The patient was still underweight, but her BMI increased from 14.7 to 17.6 kg/m2 (Table 1). She denied having suicidal thoughts and tendencies. Shortly after the completion of the ECT she was discharged from the hospital, with a recommendation to continue pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. The hospitalization described was half as long as the previous one (Figure I).

During the 6-month follow-up, with monthly outpatient visits, the patient reported a significant improvement which persisted for four months after discharge. Her mental state deteriorated slightly after that but remained stable and markedly better than it had been before the hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

We have presented here a case report of a patient with PTSD with comorbid MDD and anorexia nervosa successfully treated with ECT. We found the most significant improvement in the symptoms associated with depression, which likely had an impact on the remaining two conditions. There were no long-lasting or severe adverse effects of the ECT.

In order for PTSD to be treated it has to be appropriately diagnosed. Although our patient had developed PTSD prior to the other psychiatric disorders, it remained undiagnosed for over ten years. During that time the patient was hospitalized for psychiatric reasons three times. One of the factors that make diagnosing PTSD challenging is the high rates of comorbidity that accompany it. Nearly 50% of patients with PTSD have three or more other psychiatric diagnoses [1]. Our patient falls into this category as she suffered from MDD and AN, comorbid with PTSD.

Comorbidity worsens treatment outcomes for PTSD and other accompanying conditions [22, 23]. Some authors suggest that PTSD should be treated first, as it may be the condition underlying other disorders [24]. Other researchers point to increased difficulties in compliance, for example inconsistent attendance at trauma-focused psychotherapy sessions while experiencing severe depressive symptoms. Combining the methods recommended for all diagnoses may improve results [25]. To address our patient’s problem, we combined the first-line treatment for PTSD (EMDR) [1-4] with treatment for MDD: pharmacotherapy and ECT. Our baseline treatment of the patient’s major depressive disorder was the administration of venlafaxine and mirtazapine. Venlafaxine is also recommended in PTSD treatment guidelines. We used trazodone for the reduction of nightmares because prazosin is not available in Poland, and after one dose of clonidine the patient experienced hypotonia and dizziness [5-7]. Lamotrigine and quetiapine were used for MDD augmentation. Additionally, quetiapine and mirtazapine were supposed to have beneficial effect for patients’ lack of appetite.

The patient’s eating disorders were not severe enough to require immediate intervention.

Only one [6] of the five main guidelines [5-8, 26] for treating PTSD mention ECT, but declared that insufficient evidence exists to recommend this method. We found 6 studies [13-16, 27-29] and 14 case reports [18, 30-39] on the use of ECT in the treatment of patients suffering from PTSD and comorbid MDD. All but one [37] indicated that the use of ECT may be effective and safe in patients with these conditions. Our case supports the current body of evidence, indicating that ECT may be a safe and effective treatment method for patients with comorbid PTSD and MDD [11, 13-15, 27, 29-35, 39]. Nonetheless, there is still a need for high-quality clinical trials, which would definitely prove the efficacy of such an approach.

Before the ECT the patient’s depression was severe, with strong suicidal tendencies, which required strict supervision. By the end of the hospitalization the patient’s Beck Depression Inventory – II rating scores decreased by 21 points; this represented a significant response – from severe to moderate depression [40] without any suicidal tendencies.

The 8-point reduction on the PCL scale was unevenly distributed across different dimensions of PTSD symptoms. The patient improved in three symptom clusters: avoidance, mood and cognition, and arousal [41]. In questions associated with intrusive symptoms like nightmares and flashbacks the patient evaluated only one out of five symptoms as slightly better than before, and three as slightly worse. Such a deterioration may be associated with concomitant EMDR sessions [42]. We also found some articles suggesting that ECT may improve intrusions [30, 35, 39] and one case report showing an increase in intrusive PTSD symptoms after ECT [33]. In our case, nightmares were the only intrusive symptoms that improved, probably because ECT influences sleep architecture by decreasing rapid eye movement phase frequency [43], in which nightmares occur.

CGI, although less specific than other scales, provided an approximate assessment of changes in the patient’s mental state over time. It suggested a rapid but initially unstable improvement.

ECT decreases hospitalization time for patients with MDD [44], which was also evident in this case (Figure I). Using this treatment halved the hospitalization time for our patient, compared to her previous stay (Figure I). Had the ECT been used earlier (it started on day 40), the hospitalization period might have been even shorter.

We assumed that AN was secondary to PTSD because of the patient’s complaints (“I hate my body after what happened”, “I do not want to look like a woman, I want to feel safe”) and the similar onset time for both disorders. Therefore, we did not use any treatment specifically for anorexia. Nonetheless, in the course of treatment the patient’s weight increased significantly.

The follow-up was based on the physician’s assessment of mental state during outpatient visits. Some studies suggest that the maintenance of ECT may effectively prolong/sustain the improvement following an acute course for patients with PTSD and comorbid MDD [13, 33]. In our institution, access to this treatment modality was difficult due to the inability to perform ECT on an outpatient basis.

Before commencing with the ECT sessions, we encountered some challenges. Firstly, our proposal to begin ECT strengthened the patient’s conviction of being seriously ill and “a difficult case.” Also, the patient was afraid of being unconscious and partly naked in the presence of other people, especially men. Because of many false beliefs about ECT (such as the procedure being painful and altering brain function and personality), additional psychoeducation was necessary. A psychologist and psychiatrist worked together to inform the patient about the nature of ECT. We also provided a safe environment (mostly female staff during the procedure) and established rapport with the patient.

Despite initial attempts at using various sedatives (typical and atypical neuroleptics, hydroxyzine, pregabalin, and β-blockers), only benzodiazepines gave a satisfactory effect that enabled the reduction the need to restrain the patient. The simultaneous use of benzodiazepines and ECT may be a challenge in clinical practice as they limit the effectiveness of ECT by increasing the seizure threshold. Flumazenil is a safe and effective drug for the temporary reversal of the effect of benzodiazepine during the ECT [45]. We achieved effective seizure duration and did not observe any side effects, including symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. High (> 300 mg/d) doses of venlafaxine during ECT may increase the risk of asystole and other adverse effects [46] so we decreased the daily dose to 150 mg.

Although the effectiveness of bilateral ECT (BL-ECT) and right unilateral ECT (RUL-ECT) is considered to be similar, some studies suggested that BL-ECT may cause a faster improvement but is associated with a greater risk of cognitive side effects than RUL-ECT [47-49]. Because we needed a rapid response early in the treatment due to the high risk of suicide, we used BL- ECT. When the most dangerous symptoms subsided, we switched to RUL-ECT to avoid cognitive deterioration. As expected, the side effect decreased, and patients’ health improved.

CONCLUSIONS

Our case supports the findings from other studies, indicating that ECT may be a safe and effective method of treatment in patients with comorbid PTSD, MDD and AN. After ECT use the greatest improvement was visible in depressive symptoms; improvement in PTSD and AN was lower and seems to be a result of MDD treatement. The use of ECT may significantly shorten the time of hospitalization.