Introduction

Escherichia coli is a gram-negative bacterial species that belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family. This species includes both commensal and pathogenic strains (Leimbach et al., 2013). Pathogenic E. coli can cause a broad spectrum of diseases in humans (Belanger et al., 2011). E. coli is one of the most common pathogens that causes both community-acquired and hospital-acquired infections, including infections of the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts, peritonitis, meningitis, sepsis, and medical device-associated infections (Paterson, 2006; Mathlouthi et al., 2016). Infections caused by E. coli are associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Mathlouthi et al., 2016), and E. coli accounts for up to 90% of all urinary tract infections (UTIs) (Dromigny et al., 2005).

E. coli plays an important role in resistant bacterial populations, and it is widely used as a bio-indicator for monitoring antimicrobial resistance because of its presence in a wide range of hosts and its ability to gain resistance easily (Tadesse et al., 2012). The occurrence and susceptibility profile of E. coli shows not only substantial geographic variations but also significant differences in inhabitance and environmental ambience (Von Baum and Marre, 2005). Treatment of infections caused by pathogens such as E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae is threatened by the emergence and increase in antimicrobial resistance associated with genetic mobile elements such as plasmids that may also contain virulence genes (Hennequin and Robin, 2016). These bacterial species are proficient pathogens because they are virulent, antibiotic resistant, and epidemic in nature (Wang et al., 2014).

Pathogenic E. coli isolated from different clinical infections possesses a broad range of virulence-associated factors, including toxins, adhesions (fimbriae), lipopolysaccharides, polysaccharide capsules, proteases, and siderophores (salmochelin, yersiniabactin, and aerobactin), which are encoded by pathogenic islands and other mobile genetic elements (Bashir et al., 2012; Pitout, 2012; Wang et al., 2014).

Because of diversity in the mechanism of acquisition of resistance and virulence factors of the strains, the correlation between resistance and virulence is a complex issue and is poorly understood (da Silva and Mendonça, 2012; Ramirez et al., 2014; Hennequin and Robin, 2016). Knowledge and understanding of correlations between antibiotic resistance, virulence factors, and phylogenetic background would therefore be helpful and enable antibiotic treatment of several infections (Wang et al., 2014). The present study was conducted to determine whether siderophores production by E. coli strains has a role in its antibiotic resistance.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Thirty-two clinical E. coli strains were collected from different clinical settings in Cairo, Egypt (12 strains were obtained from Al Salam International Hospital, 9 from Ain Shams Specialized Hospital, 4 from the National Cancer Institute, 3 from Demerdash Hospital, and 1 strain from Samir Shaker Laboratory) and used in this study. Of these 32 strains, 28 were isolated from urine, 2 from sputum, 1 from pus, and 1 from wound. These strains were grown at 37°C for 24 h on different selective and differential ready-to-use dehydrated media to confirm their identification. These media included eosin methylene blue agar (EMBA), brilliant green agar (BGA) (Lab M, United Kingdom), MacConkey agar (MACA), Sorbitol MacConkey agar (SMACA) (HiMedia Laboratories, India), and violet red bile agar (VRBA) with MUG (Biolife, Italia).

Screening for antibiotic susceptibility

Antibiotic susceptibility of the 32 clinical E. coli strains was tested using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method (Bauer et al., 1966) with different antibioticdiscs. These antibiotics (Bioanalyse, Turkey) included gentamycin (GMN)10 μg, kanamycin (KAN) 1 mg, rifampicin (RD) 5 μg, ampicillin (AMP) 10 μg, amoxycillin (AML) 10 μg, penicillin (P) 10 U, cefoxitin (FOX) 30 μg, cephalexin (CL) 30 μg, ceftriaxone (CRO) 30 μg, cefixime (CFM) 5 μg, cefaclor (CEC) 30 μg, cefoperazone (CFP) 75 μg, cefadroxil (CFR) 30 μg, cefoperazone/sulbactam (CFS) 75/30 μg, cefuroxime sodium (CXM) 30 μg, vancomycin (VA) 30 μg, norfloxacin (NOR) 10 μg, ofloxacin (OFX) 5 μg, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SXT) 25 μg. All data were evaluated according to CLSI criteria (CLSI, 2019).

Siderophores production

All strains were screened for siderophores production qualitatively according to the method of Alexander and Zuberer (1991). Overnight cultures were grown on Chrome Azurol Sulfonate (CAS) agar plates. A yellow halo surrounding the bacterial colony after 4–5 days of incubation at 37°C indicated positive siderophores production. Siderophores production by E. coli strains grown in M9 medium (Maniatis et al., 1982) was also determined quantitatively by using CAS liquid medium according to Schwyn and Neilands (1987) and by the method of Alexander and Zuberer (1991) in which 2-[N-morpholino] ethanesulfonic acid (MES buffer) (Fisher Scientific, Belgium) was used as a buffer solution instead of solution 2 in the original method.

16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The genomic DNA of E. coli strains 21 and 49, the most potent siderophores producers, was extracted using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, Lithuania). A PCR thermal cycler (Biometra® cycler personal) was used for 16S rRNA gene amplification under the following programmed conditions: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 1.5 min, 59°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min, and a final 10 min extension at 72°C. PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using two universal oligonucleotide bacterial primers, namely 16S rRNA forward primer: 5′–GAG TAA TGT CTG GGA AAC TGC CT–3′, and 16S rRNA reverse primer: 5′–CCA GTT TCG AAT GCA GTT CCC AG–3′. The purified PCR products were sequenced in an automated sequencer (ABI Prism 3730XL, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at Macrogen Inc., Korea. The sequences were analyzed using Geneious Pro 8.1.1,. and sequence identity search was then performed using BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software (Geneious Pro 8.1.1). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining tree method (Saitou and Nei, 1987), and the genetic distance model was developed using the Tamura-Nei model (Tamura and Nei, 1993).

Plasmid preparation and curing

Small-scale preparation of plasmids from E. coli strains 21 and 49 was performed according to Sambrook et al. (1989). Plasmid curing trials were then performed using different methods (Trevors, 1986), such as growing E. coli strains in nutrient broth (NB) at elevated temperatures of 40, 45, and 50°C (their highest sublethal doses) for 24–48 h. The bacterial strains were also grown in NB supplemented with sterilized mitomycin C (15 μg/ml) or sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (10%) at 37°C for 24–48 h. The developed colonies were picked up and streaked on the surface of both LB agar plates (master plates) and LB agar plates supplemented with GMN, AMP, SXT, and CRO. The cured colonies were then screened for antibiotic sensitivity and subjected to qualitative and quantitative assessment of siderophores production.

Bacterial transformation

Bacterial transformation was performed according to Bimboim and Doly (1979). E. coli strain DH5α was prepared as competent cells and then transformed with plasmids isolated from E. coli strains 21 and 49, individually. Screening for antibiotic susceptibility was performed, and qualitative and quantitative siderophores production by the transformed competent cells was determined as previously described.

Results

All clinical E. coli strains were grown on different selective and differential media. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the growth of the strains appeared as green metallic sheen colonies on EMBA; pink colonies surrounded with precipitation on MACA; yellow to yellowgreen colonies surrounded with precipitation on BGA; colorless colonies on SMACA, and colonies that do not fluorescence blue under long wavelength UV light on VRBA with MUG. These observations confirmed that these strains were E. coli.

Antibiotic susceptibility of E. coli strains

The 32 clinical E. coli strains used in this study were tested for antibiotic susceptibility by using the KirbyBauer disc diffusion method. Data presented in Table 1 revealed that 16 of the 32 strains (50%) and numbered (2, 6, 15, 23, 26, 26′, 33, 49, 55, 66, 70, 71, 73, 78, 95, and 117) were found to be resistant to all antibiotic groups. Nine of the remaining strains (28.125%) were resistant to 6 antibiotic groups. Additionally, 6 strains (18.75%) and 1 strain (3.125%) were found to be resistant to 5 and 4 antibiotic groups, respectively. The results also showed that the highest resistance (100%) was observed for ansamycins, cephalosporins, β-lactams, and glycopeptide antibiotics, followed by 84.4 and 81.2% resistance to quinolones and sulfonamide, respectively. However, only one strain (strain number 15) showed complete resistance to aminoglycosides. In addition, 18 strains (56.2%) and 4 strains (12.5%) were resistant to gentamycin and kanamycin, respectively. Statistical analysis of the obtained results by one-way ANOVA showed that the differences were significant at P < 0.0001 as shown in supplementary material (Table S1).

Table 1

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of the 32 clinical E. coli strains according to CLSI (2019)

[i] GMN – gentamycin (10 μg), KAN – kanamycin (1 mg), RD – rifampicin (5 μg), AMP – ampicillin (10 μg), AML – amoxycillin (10 μg), P – penicillin (10 U), FOX – cefoxitin (30 μg), CL – cephalexin (30 μg), CRO – ceftriaxone (30 μg), CFM – cefixime (5 μg), CEC – cefaclor (30 μg), CFP – cefoperazone (75 μg), CFP – cefoperazone (75 μg), CFR – cefadroxil (30 μg), CFS – cefoperazone/sulbactam (75/30 μg), CXM – cefuroxime sodium (30 μg), VA – vancomycin (30 μg), NOR – norfloxacin (10 μg), OFX – ofloxacin (5 μg), SXT – sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (25 μg); S – sensitive, I – intermediate, R – resistance

Siderophores production

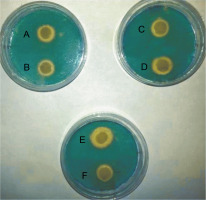

All E. coli strains used in this study were qualitatively screened for siderophores production by using CAS agar plates. The presence of yellow halos around the bacterial growth indicated the production of siderophores (Fig. 1). The results revealed that 23 E. coli strains produced siderophores based on the differences in the diameters of yellow halos, whereas 9 strains did not show siderophores production. The largest yellow halo was produced by E. coli strain 71, whereas the smallest halos were produced by E. coli strains 1, 49, 58, and 95. In contrast, none of the E. coli strains 6, 22, 23, 26, 66, 70, 81, 101 and 120 produced yellow halos on CAS agar plates. The amount of siderophores produced by E. coli strains tested in the present study was also determined quantitatively by using the method of Alexander and Zuberer (1991) with some modification. The obtained results indicated that the highest percentage of the produced siderophores was 79.9% and was shown by E. coli strain 21, followed by strains 49 and 96 with 46.62 and 45.19% siderophores unit, respectively. The lowest percentage of siderophores was produced by E. coli strains 23 and 66 with 6.74 and 6.45% siderophores unit, respectively. In contrast, no siderophores were detected from E. coli strains 6, 10, 29, 73,101, and 122 by this method (Table 2). Statistical analysis of siderophores production quantitatively by clinical E. coli strains by using simple linear regression showed that the differences were not significant at P = 0.1280, as shown in supplementary material (Table S2).

Table 2

Siderophore production by the clinical E. coli strains tested in this study

| Bacterial strains | Siderophore production | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwyn and Neilands (1987) | Alexander and Zuberer (1991) | |||||

| Ar | As | siderophore production [%] | Ar | As | siderophore production [%] | |

| 1 | 0.619 | 0.287 | 53.6 | 0.697 | 0.613 | 12.05 |

| 2 | 0.619 | 0.276 | 55.4 | 0.697 | 0.572 | 17.93 |

| 6 | 1.009 | 1.217 | – | 0.697 | 1.066 | – |

| 10 | 1.009 | 1.155 | – | 0.697 | 0.839 | – |

| 15 | 0.977 | 0.620 | 36.5 | 0.697 | 0.392 | 43.75 |

| 21 | 0.977 | 0.866 | 11.3 | 0.697 | 0.140 | 79.9 |

| 22 | 1.009 | 1.280 | – | 0.697 | 0.611 | 12.38 |

| 23 | 0.619 | 0.301 | 51.37 | 0.697 | 0.650 | 6.74 |

| 24 | 0.977 | 0.952 | 2.5 | 0.697 | 0.505 | 27.54 |

| 25 | 1.009 | 1.077 | – | 0.697 | 0.452 | 35.15 |

| 26 | 0.619 | 0.311 | 49.7 | 0.697 | 0.446 | 36.01 |

| 26 | 0.619 | 0.252 | 59.28 | 0.697 | 0.489 | 29.84 |

| 29 | 1.009 | 0.638 | 36.7 | 0.697 | 0.700 | – |

| 33 | 0.977 | 0.542 | 44.5 | 0.697 | 0.590 | 15.35 |

| 34 | 0.977 | 0.930 | 4.8 | 0.697 | 0.576 | 17.36 |

| 49 | 0.619 | 0.253 | 59.1 | 0.697 | 0.372 | 46.62 |

| 52 | 0.619 | 0.420 | 32.1 | 0.697 | 0.628 | 9.89 |

| 55 | 1.009 | 0.646 | 35.97 | 0.790 | 0.465 | 41.26 |

| 58 | 0.977 | 0.538 | 44.9 | 0.697 | 0.593 | 14.92 |

| 65 | 1.009 | 0.598 | 40.7 | 0.697 | 0.600 | 13.9 |

| 66 | 1.009 | 0.738 | 26.8 | 0.697 | 0.652 | 6.45 |

| 70 | 0.977 | 0.810 | 17 | 0.697 | 0.640 | 8.17 |

| 71 | 1.009 | 1.196 | – | 0.697 | 0.541 | 22.38 |

| 73 | 0.977 | 0.572 | 41.4 | 0.697 | 0.708 | – |

| 78 | 0.619 | 0.325 | 47.4 | 0.697 | 0.610 | 12.48 |

| 81 | 1.009 | 1.129 | – | 0.697 | 0.444 | 36.29 |

| 95 | 0.619 | 0.279 | 54.9 | 0.697 | 0.558 | 19.94 |

| 96 | 1.009 | 1.145 | – | 0.697 | 0.382 | 45.19 |

| 101 | 0.619 | 0.270 | 56.38 | 0.697 | 0.751 | – |

| 117 | 1.009 | 0.809 | 19.8 | 0.790 | 0.643 | 14.7 |

| 120 | 1.009 | 1.083 | – | 0.697 | 0.595 | 14.63 |

| 122 | 0.619 | 0.274 | 55.7 | 0.697 | 0.939 | – |

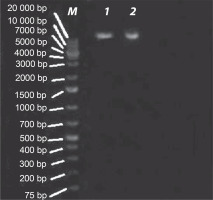

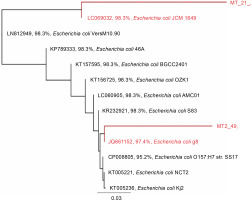

Analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences

Based on the alignment of 16S rRNA gene sequences from the GenBank database, the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the tested strains showed the highest similarity to that of E. coli (Fig. 2). Strain 21 was most similar to E. coli JCM 1649 with 98.3% identity, whereas strain 49 was most similar to E. coli g8 with 97.4% identity.

Fig. 2

Rooted phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of the 16S rRNA gene of strains 21 and 49 and the 16S rRNA gene sequence aligned in MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004); the tree was constructed using the Geneious Tree Builder option (Genetic distance model: Tamura-Nei, tree builder methods: Neighbor-joining, and Outgroup: ECORRD); the tree was rooted with E. coli as a member of the Enterobacteriaceae family (Drummond et al., 2014)

Plasmid curing

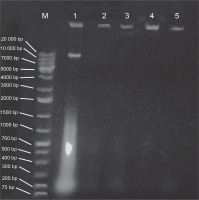

E. coli strains 21 and 49 were tested for harboring of plasmids by small-scale preparation of plasmid and agarose gel electrophoresis. The obtained results revealed that plasmids were detected in both samples, wherein 2 or 3 bands represented the different forms of plasmids such as supercoiled, nicked relaxed, and linear forms (Fig. 3). To obtain plasmid-cured E. coli strains, strains 21 and 49 were grown in LB broth medium under different curing conditions, as mentioned in Materials and methods. The obtained results indicated that the absence of plasmid-cured mutants of E. coli strain 21. Moreover, the growth of E. coli strain 49 in NB overnight at 50°C yielded 10 colonies on the nutrient agar (NA) plate. Of these colonies, only 4 failed to develop on NA plates containing GMN, AMP, SXT and CRO, individually. These colonies were found to be devoid of plasmids (Fig. 4). Moreover, these plasmid-cured strains failed to grow on CAS agar medium, and no siderophores were detected when these strains were grown in M9 medium and assayed for siderophores production by using the modified CAS assay method (Table 3).

Table 3

Quantitative assay of siderophores produced by the plasmid-cured strains and the native strain of E. coli strain 49 by using the modified CAS assay method

| Strain 49 | Ar | As | Siderophore unit [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native strain | 0.690 | 0.395 | 42.75 | |

| Cured strains | 1 | 0.690 | 0.833 | – |

| 2 | 0.690 | 0.787 | – | |

| 3 | 0.690 | 0.791 | – | |

| 4 | 0.690 | 0.780 | – |

Screening for antibiotic sensitivity and siderophores production by transformed E. coli DH5α

E. coli DH5α was transformed with plasmids isolated from both E. coli strains 21 and 49, individually. The transformed E. coli DH5α colonies were then screened for antibiotic sensitivity and siderophores production qualitatively and quantitatively in the CAS-containing medium. The results showed that E. coli DH5α cells transformed with the plasmid isolated from E. coli strain 49 were resistant to antibiotics belonging to β-lactams, cephems, and glycolipids. However, E. coli DH5α cells transformed with the plasmid isolated from E. coli strain 21 were resistant only to antibiotics belonging to β-lactams and cephems (Table 4). Statistical analysis of antibiotic susceptibility of plasmid-cured and plasmid-transformed E. coli strains by one-way ANOVA showed that the differences were not significant at P = 0.4442, as shown in supplementary material (Table S3). Moreover, native and transformed E. coli DH5α cells failed to grow on CAS agar medium, and no siderophores were detected from them using the modified CAS assay.

Table 4

Antibiotic susceptibility of the plasmid-cured and plasmid-transformed E. coli strains according to CLSI (2019)

Discussion

Antibiotics are the most important therapeutic agents used for treating bacterial infections, and therefore, an extensive increase in the incidence of antibioticresistant bacteria is a major worldwide concern (Sabtu et al., 2015; Church and McKillip, 2021). Microorganisms acquire drug resistance through various mechanisms such as recombination of foreign DNA in bacterial chromosome, horizontal gene transfer, and alteration in genetic material (Von Baum and Marre, 2005; Kiffer et al., 2007; Pondei et al., 2012).

E. coli plays an important role in resistant bacterial populations, and it is widely used as a bio-indicator for monitoring antimicrobial resistance because of its presence in many different hosts and its ability to gain resistance easily (Tadesse et al., 2012).

In the present study, 32 clinical E. coli strains were tested. These E. coli strains were resistant to at least 14 antibiotics out of the 19 drugs tested, which belonged to different chemical groups. Thirty-one strains were classified as extensively drug-resistant (XDR) (i.e., strains susceptible to only one or two antibiotic groups), and only one strain was classified as pan drug-resistant (PDR) (i.e., strains resistant to all antibiotic groups) (Magiorakos et al., 2011). The increased resistance of bacteria to antibiotics could be attributed to the dramatic increase in the consumption of different antibiotics without clinical confirmation (Malik and Bhattacharyya, 2019), in addition to the overuse of antibiotics in animal nutrition (Ma et al., 2021). In Cairo, increased resistance was observed to different antibiotic classes among gram-positive cocci and gram-negative bacilli strains isolated from blood culture (Khalifa et al., 2019; Fahim, 2021).

The antibiotic resistance pattern of the tested E. coli strains showed high resistance rates (100%) to antibiotics belonging to β-lactams, ansamycins, glycolipids, and 6 cephem antibiotics; 84.3% resistance to quinolones, and 81.25% resistance to sulfonamides. The strains also showed moderate resistance (56.25%) to GMN and the lowest resistance (12.5%) to KAN–two antibiotics belonging to aminoglycosides. As a comparative study, 50 clinical strains of E. coli were isolated from 5 hospitals in Cairo, Egypt during 1999–2000. High and moderate resistance to AML (94%) and GMN (48%), respectively, was recorded (El Kholy et al., 2003). These results agree to a great extent with the results of the present study.

High resistance to AML followed by sulfonamides and low resistance to GMN have been reported in many studies, including some retrospective studies (Moroh et al., 2014; Chakrawarti et al., 2015; Adefisoye and Okoh, 2016; Tajbakhsh et al., 2016). As ampicillin was first introduced in 1961, the long-term use of this antibiotic has been proposed to be responsible for increased resistance (Tadesse et al., 2012). Although resistance to β-lactam antibiotics is mainly attributed to the production of β-lactamases, other mechanisms such as AmpC-type cephalosporinases and changes in porin channels could be involved (Abdallah et al., 2015; Khalifa et al., 2019).

Although sulfonamides were not largely used in the United States, Stockholm, and Sweden, an increased resistance of clinical E. coli strains to this antibiotic group was observed over time (Kronvall, 2010). Ali et al. (2014) reported that the highest resistance level of 86.25% (69 of 80 strains) of uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strains isolated from nonhospitalized patients was recorded against trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ).

Although quinolones are largely considered as the antibiotic of choice in treating many pathogenic bacterial infections, including UTIs, increased resistance to these newer compounds has been observed (Ali et al., 2014; Khalifa et al., 2019). In another study, 51% (65 of 129) of clinical E. coli strains isolated in Poland were resistant to nalidixic acid (quinolone group) (Adamus-Bialek et al., 2013). In Shanghai, the resistance rate of UPEC to quinolones increased from 58.7% in 2008 to 71.2% in 2014 (Wang et al., 2014). Rath and Padhy (2015) studied the antibiotic resistance pattern of 1642 E. coli strains to fluoroquinolone antibiotics and reported that 575 of 832 hospital-acquired (HA) and 567 of 810 communityacquired (CA) E. coli strains showed resistance. In another study, 58 and 43 strains of 80 biofilm-producing UPEC were resistant to nalidixic acid and norfloxacin (quinolone antibiotics) with the resistance rate of 72.5% and 53.75%, respectively; however, 43 and 26 strains of 50 nonbiofilm producers were resistant to the same antibiotics (Tajbakhsh et al., 2016). In the present study, the level of resistance to quinolones was 84.3%, which exceeded the abovementioned findings.

Resistance to quinolones is mainly caused by mutations in the target enzyme DNA gyrase (gyr A and gyr B ) genes in the gram-negative bacteria; however, the plasmid encoding the Qnr protein may also confer resistance against this class of antibiotics (Jacoby, 2005; Leski et al., 2016). In E. coli, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the predominant mechanisms of resistance to antibiotics (Leski et al., 2016; Malekzadegan et al., 2019; Kakoullis et al., 2021).

In the present study, aminoglycosides were found to be the most effective antibiotics relative to the other classes of antibiotics. Shanahan et al. (1993) suggested that the lower resistance rate (7.5%) of E. coli isolates to aminoglycosides was attributed to the lower usage of this drug as compared to ampicillin and trimethoprim, which are older and the most widely used antibiotics worldwide. In the United States, Tadesse et al. (2012) conducted a retrospective study for antibiotic resistance change pattern of clinical E. coli strains during 1950–2002, and rare gentamycin resistance was observed. However, in Sweden, Kronvall (2010) conducted a survey over the period of 1979 to 2009 and observed a slight increase in resistance to gentamycin in clinical E. coli strains at the end of the period, although it was increased from 1.42% in 2006 to 2.45% in 2009.

The common resistance mechanism against aminoglycosides in E. coli involves the modification of aminoglycosides by aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. The main enzymes encountered in E. coli are aminoglycoside acetyltransferases, phosphotransferases, and nucleotidyl transferases as these enzymes prevent the binding of the drug to ribosomes of the cell (Bodendoerfer et al., 2020; Kakoullis et al., 2021).

The results obtained in the present study indicated that the resistance of E. coli strains to the first-generation cephalosporins was 100%, whereas it was 87.5% for second- and third-generation cephalosporins. In a previous study, the resistance rate of 80 clinical E. coli strains to the first-, second-, and third-generation cephalosporins was 70, 53.7, and 58.5%, respectively (Ali et al., 2014). Similar findings were reported in India by Rath and Padhy (2015). Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins was also recorded in other investigations (Van Der Steen et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2019; Prasada et al., 2019). Additionally, Gashe et al. (2018) reported that 73% and 65% of the tested clinical E. coli isolates were resistant to ceftriaxone and ceftazidime, respectively. Moreover, in another study, none of the 129 clinical E. coli strains were resistant to cefuroxime sodium (Woo et al., 2019).

Iron is one of the most important microelements required by all living organisms for various metabolic processes essential for growth and survival (Kramer et al., 2020). Although iron is the fourth element in the earth’s crust under aerobic conditions, the bioavailability of iron is extremely restricted where it exists in an insoluble trivalent state as oxides or hydroxides (Emerson et al., 2012). Therefore, under conditions of iron limitations, many microorganisms are induced to produce and secrete low-molecular-weight iron-chelating compounds known as siderophores (Schwyn and Neilands, 1987; Ahmed and Holmström, 2014). Several studies have demonstrated that both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria synthesize and secrete siderophores into the environment under iron-limited conditions, where they bind ferric iron (Fe III) with high affinity (Saha et al., 2016).

Many commensal E. coli strains can produce these virulent-associated siderophores (Searle et al., 2015). Therefore, siderophores can be considered as a putative virulence factor rather than being considered as typical virulent factors directly involved in infection by pathogenic E. coli strains, where they contribute to increase in fitness, adaptability, competitiveness, chance of survival, and colonization in human body (Holden and Bachman, 2015). In contrast, other studies have considered siderophores production as a virulence factor in pathogenic bacteria (Vagrali, 2009; Lisiecki, 2013; Hennequin and Robin, 2016) and in particular pathogenic E. coli, where siderophores are considered as a target to achieve antibacterial control and restrict bacterial growth (Massip and Oswald, 2020). Enterobactin production was found to play an important role in E. coli colonization in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) (Pi et al., 2012). However, the ability to synthesize additional siderophores such as yersinobactin and salmochelin is generally correlated with virulence, especially for extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) (Garénaux et al., 2011; Sarowska et al., 2019). This was also reported in other studies. Searle et al. (2015) found that plant-associated E. coli strains isolated from leafy green vegetables produced significantly less amount of siderophores than fecal-associated strains. In contrast, 97.5% of 160 UPEC strains were found to be positive siderophores producers as compared to only 4% of 50 fecal-associated strains, suggesting the frequent but unconfirmed role of siderophores in pathogenicity (Vagrali, 2009).

In the present study, the production of siderophores by the 32 clinical E. coli strains was determined both qualitatively using the CAS agar medium (Alexander and Zuberer, 1991) and quantitatively using the CAS assay solution method of Schwyn and Neilands (1987) and the modified CAS assay solution method of Alexander and Zuberer (1991). In the qualitative detection of siderophores, the results showed that 23 of the 32 pathogenic E. coli strains produced yellow halos with different diameters around the bacterial growth, indicating siderophores production, whereas 9 E. coli strains failed to grow on the CAS agar medium. The quantitative detection of siderophores was first performed according to the method of Schwyn and Neilands (1987) by using the CAS assay solution, and it was observed that, after mixing piperazine-HCl buffer solution with the CAS dye indicator solution, the blue CAS dye precipitated after a short period. This problem was also reported by Alexander and Zuberer (1991). To overcome this issue, the CAS assay solution medium was freshly prepared just before the beginning of the assay; however, it also yielded varying absorbance of reference solution (Ar), and consequently, inconsistent results were obtained using this procedure. In contrast, after using the modified CAS assay solution method of Alexander and Zuberer (1991), it was observed that the substitution of piperazine-HCL buffer with MES buffer resulted in stable blue CAS dye, and consistent results was obtained. Alexander and Zuberer (1991) also reported that bacteria that failed to produce siderophores on CAS agar often produced siderophores in a liquid medium with limited iron concentration that could be measured with the modified CAS assay solution. This was also observed in the present study, as 7 strains failed to produce siderophores on CAS agar but produced them in a liquid M9 medium at concentrations measured with the modified CAS assay solution. This could be attributed to the toxicity of hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HDTMA) to some bacterial strains as reported by Alexander and Zuberer (1991). In contrast, other strains failed to produce siderophores in the M9 medium, although they produced a yellow halo on CAS agar. This could be because the growth and amount of siderophores produced by an organism under different culture conditions are different (McRose et al., 2017; McRose et al., 2018; Armin et al., 2021; Kang-Yun et al., 2021)

Although the genes responsible for regulating siderophores are located on the chromosome (Thode et al., 2018; Massip and Oswald, 2020), it has been reported that the genes responsible for siderophores production were originally plasmid encoded (Faoro et al., 2019; Sarowska et al., 2019; Choby et al., 2020; Heiden et al., 2020) .

In the present study, four plasmid-cured strains derived from E. coli strain 49 failed to grow on both CAS agar and M9 media, and no siderophores were detected using the modified CAS assay solution. These results might indicate that the siderophores-encoding genes are located on the plasmid rather than on chromosomal DNA. However, E. coli strain DH5α transformed with the plasmids obtained from E. coli strains 21 and 49 failed to produce siderophores. This could be because the iron assimilation system in bacteria and fungi is regulated by the chromosomal fur (ferric uptake regulation) gene product, a universal iron assimilation system regulator in E. coli and other bacteria (Klebba et al., 2021; Seyoum et al., 2021). The fur gene product (fur protein) acts as a negative repressor for siderophores transcription (Pi and Helmann, 2018; Bradley et al., 2020; Santos et al., 2020). In particular, the E. coli fur protein is a 17 kDa polypeptide that under iron-rich conditions binds the divalent ion (Fe2+) and binds to target sequences or the recognition site (generally designated as the fur box or iron box with the assent sequence 5′–GATAATGATAATCATTATC–3′) and inhibits transcription wherein all genes for siderophores biosynthesis are repressed by the metal (Parveen et al., 2019; Doni et al., 2020). In contrast, under iron-limited condition, all genes for siderophores biosynthesis are expressed, where Fe2+ is released and subsequently, the fur protein acquires a configuration wherein it cannot bind to the fur box; consequently, RNA polymerase starts the transcription of genes for siderophores biosynthesis (Zhang et al., 2020).

Screening of plasmid-cured mutants derived from E. coli strain 49 for antibiotic susceptibility showed that these colonies were susceptible to all the tested antibiotics, indicating that the resistance to these antibiotics is plasmid encoded. However, E. coli strain DH5α transformed with the plasmid isolated from E. coli strain 49 acquired resistance only to β-lactams and cephems. It is likely that some regulators encoded by the chromosomal materials of E. coli strain 49 act as activators (switching on) for the genes responsible for resistance against the remaining antibiotic groups. These regulators could be absent in E. coli DH5α (Banda et al., 2019; Jung et al., 2021).

The obtained results suggest the presence of a positive correlation between antibiotic resistance and siderophores production in the tested E. coli strains. A similar finding was reported in an analogous study, where an apparent association was observed between increased resistance to fluoroquinolones and siderophores production in 55 strains of Enterococcus (Lisiecki, 2013).

In the literature, the majority of work on the relationship between the presence of different virulence factors and antibiotic resistance indicates a positive link between them. However, because little is known about the type and extent of this relationship, future studies are required to investigate this point.

Conclusions

The present study provides data on siderophores production and the antibiotic susceptibility pattern of 32 clinical E. coli strains collected from different clinical settings in Cairo, Egypt. The obtained results revealed that 31 strains could be considered as XDR and only one strain was PDR. Furthermore, 23 E. coli strains produced siderophores, whereas 9 strains failed to do so. E. coli strains 21 and 49 were found to be the most potent siderophores producers. The identity of the two strains was further confirmed by a molecular approach. The role of siderophores production in antibiotic resistance of these two strains was also investigated. Plasmid-cured bacterial colonies derived from strain 49 were susceptible to all the tested antibiotics. E. coli DH5α cells transformed with the plasmid isolated from E. coli strain 21 or strain 49 were susceptible to ansamycins, quinolones, and sulfonamides. In contrast, both plasmidcured and plasmid-transformed strains did not produce siderophores, indicating that the genes responsible for siderophores production could be located on plasmids and regulated by genes located on the chromosome. The findings of the present study suggest a positive correlation between antibiotic resistance, especially to quinolones and sulfonamides, and siderophores production by the E. coli strains tested in this study.