Introduction

Plants contain a huge amount of bioactive compounds that are being used worldwide for various purposes, especially in ethnomedicine. These compounds range from a myriad of secondary and primary metabolites such as flavonoids, alkaloids, polyphenols, and bioactive proteins, which can be used in targeted therapy and treatment of diverse microbial diseases (Van Holle and Van Damme, 2018; Górniak et al., 2019; Othman et al., 2019; Bilanda et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2020; Taiwo et al., 2020; Mammari et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). An increase in microbial resistance and detrimental environmental consequences associated with the use of chemical antimicrobial agents has also contributed to the search for natural plant-based alternatives, especially those with protein origin (Vandenborre et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2019).

Lectins are unique proteins or glycoproteins, having at least one domain devoid of catalytic activity and capable of binding specific glycan moieties reversibly (Alen’kina et al., 2014; Nubi et al., 2021). These proteins are heterogeneous in structures and proficient in agglutinating or precipitating cells and carbohydrate-relate structures via specific interactions (Singh et al., 2016; Adedoyin et al., 2021). Lectins mediate a wide range of biological and biochemical processes in many organisms, such as nitrogen fixation, cellular development, mitogenesis, symbiosis, immunomodulation, and defense (Smýkal et al., 2015; Osman and Konozy, 2017; Rambo et al., 2019; Van Holle and Van Damme, 2019; Fonseca et al., 2022a).

Belonging to the legume family (Fabaceae) and characterized by peculiar red flower coloration, the genus Erythrina is widely distributed across the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Members of this genus comprise more than one hundred species, which are rich in many bioactive molecules. However, lectins have only been detected in a few members of Erythrina (Focho et al., 2009; Doughari, 2010; Otimenyin and Uzochukwu, 2010; Atsamo et al., 2013).

Erythrina senegalensis is generally used for ethnomedicinal purposes in Africa, especially in the traditional treatment of ailments such as arterial hypertension, gastrointestinal disorders, leprosy, diabetes, and hemorrhoids (Doughari et al., 2010). Erythrina spp. possess anxiolytic and anticonvulsant properties, especially in the central nervous system (Focho et al., 2009). These pharmacological activities of E. senegalensis are attributable to bioactive molecules inherent in them (Atsamo et al., 2013; Nembo et al., 2015; Nordström R, Malmsten et al., 2017; Armas et al., 2019; Van Holle and Van Damme, 2019).

Evolutionary relationships and functional diversity of genes and proteins are usually analyzed using phylogenetic analysis (Song et al., 2018). Exploring the similarities between sequences by mapping the existing data of characterized proteins belonging to a particular phylogenetic family tree can provide predictive insights into the functions and biochemical properties of members belonging to the family (Murphy et al., 2011). In the present study, the antimicrobial activity of purified lectin from E. senegalensis seeds was investigated, and phylogenetic analysis of the gene encoding lectin with other legume lectins was carried out to identify their evolutionary and functional relationship.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Glutaraldehyde, bovine serum albumin (BSA), sugars (glucose, lactose, maltose, mannose, sorbose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, and mannitol), acrylamide, ammonium persulfate, N,N,N ,N-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), sodium dodecyl sulfate, agarose, and coomassie brilliant blue R250 were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, Missouri, USA. Sepharose 4B and Sephadex G-150 were bought from Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Uppsala, Sweden. Nutrient agar and nutrient broth were from Lab M Ltd, Lancashire, United Kingdom. Gel-loading dye (BioLabs ®, B7025S), ethidium bromide, deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), Taq polymerase, DNA master mix, 100-bp DNA ladder (BioLabs ®, NO551S), and ZYMO DNA Extraction Kit were purchased from South Africa (Inqaba Biotech, Hatfield Pretoria). All other reagents and chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade.

Selected microbial species

Erwinia carotovora, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus, Aspergillus niger, Fusarium species, Penicillium camemberti, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis, Trichophyton interdigitale, and Trichoderma species were obtained from the culture collection of the Department of Microbiology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Collection and identification of E. senegalensis seeds

The E. senegalensis plant was collected from a regrowth forest located 7°31′9″N 4°31′36″E within the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Seeds were identified at the IFE HERBARIUM, Department of Botany, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria, where the plant was deposited, with the voucher specimen number IFE-17749.

Purification and hemagglutinating activity of E. senegalensis lectin (ESL)

Purification and hemagglutinating activity analysis of ESL were conducted as described in our previous study (Kuku et al., 2012). Purification involves a combination of ammonium sulfate precipitation, gel filtration on a Sephadex G-150 column, and affinity chromatography on a lactose-sepharose 4B column. In brief, E. senegalensis seeds (50 g) were pulverized and defatted using petroleum ether. The obtained flour was air-dried at room temperature and extracted with 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2 (1 : 10 w/v), at 4°C for 24 h. The resulting mixture was centrifuged (6000 rpm, 30 min), and the supernatant was collected as a crude lectin extract. Hemagglutinating activity of lectin was determined in a 96-well microtiter plate. The crude lectin aliquot (100 μl) was serially diluted with PBS (100 μl), and 50 μl of erythrocyte suspension (4% v/v) was added to each well. The resulting mixture was left undisturbed for 60 min at room temperature. Hemagglutinating activity was expressed as units taken to be the reciprocal of the highest dilution that shows visible agglutination. Specific activity was expressed as units per mg protein. In the purification stage, the crude lectin extract was subjected to 70% ammonium sulfate precipitation and left overnight (4°C). The resulting precipitate was collected by centrifugation (6000 rpm, 30 min). The recovered precipitate was resuspended in PBS, pH 7.2, and dialyzed against PBS and distilled water for 48 h. An aliquot (4 ml, approximately 28 mg protein) of ammonium sulfate dialysate was loaded on the Sephadex G-150 column (2.5 × 40 cm) equilibrated with PBS. Fractions (4 ml) were collected at a flow rate of 30 ml/h. Elution was monitored at 280 nm, and the hemagglutinating activity of the fractions was assayed. Active peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed for 48 h. Then, an aliquot (2 ml, approximately 12 mg protein) of the pooled Sephadex G-150 active fraction was layered on the Lactose-Sepharose 4B column (1.5 × 10 cm) equilibrated with PBS. Unadsorbed protein was washed with the equilibration buffer, and the adsorbed protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 0.2 M lactose. Fractions (1 ml) were collected at a flow rate of 20 ml/h. Elution was monitored at 280 nm, and the hemagglutinating activity of the fractions was assayed. Active peak fractions were pooled, dialyzed exhaustively (against PBS and distilled water), lyophilized, and kept frozen at −20°C. The protein concentration of ESL was determined at each purification stage following the method of Lowry et al. (1951). Purification was repeated several times to obtain pure ESL in sufficient quantities for antimicrobial study. The purity and molecular weight of ESL were determined using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 12.5% acrylamide gel using low-molecular-weight protein markers (Nubi et al., 2021).

Analysis of antimicrobial activity of ESL

Agar well diffusion method was used to analyze the antimicrobial activity of ESL against selected pathogenic microorganisms (Cheesbrough, 2006). In brief, fungi were cultivated on potato dextrose broth at 25°C for 48–72 h, whereas bacteria were cultivated on nutrient broth at 37°C for 24 h. The microbial cell density of both cultures was standardized (108 CFU/ml of 0.5 McFarland standards) at 600 nm. A sterile swab stick moistened with the inoculum was spread on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and Mueller Hinton agar (MHA) for fungi and bacteria, respectively. Then, 6-mm-diameter wells were bored equidistant from each other using a sterile cock borer into the respective agar media and filled with an equal volume (50 μl) of ESL (0.1–0.4 mg/ml). Fluconazole (1 mg/ml) and streptomycin (1 mg/ml) were used as the positive control for fungi and bacteria sensitivity, respectively, whereas PBS buffer was used as the negative control. Plates were incubated at 25°C for 48–72 h for fungi and 37°C for bacteria. Zones of inhibition were measured in millimeters.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ESL

MIC analysis of ESL was carried out following the method of Cheesbrough (2006). In brief, a serial dilution of ESL was prepared. Aliquots (2 ml) of the different concentrations were added to 18 ml of presterilized malt extract agar and Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) for bacteria and fungi at 40°C to achieve a final concentration regimen of 0.05 and 10 mg/ml, respectively. Respective media were poured into sterile petri plates and allowed to set. The surface of the media was dried under laminar flow before streaking with 18-h-old bacterial and fungal cultures. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and 25°C for up to 72 h for bacteria and fungi, respectively, and then, they were examined for the presence or absence of growth. The MIC was taken as the lowest concentration that prevented the growth of the test microorganism.

Isolation of genomic DNA (gDNA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of ESL gene

E. senegalensis gDNA was extracted using the ZYMO Plant DNA Mini Kit (ZYMO Research, California, USA). The purity of the isolated gDNA was evaluated by measuring the absorbance quotient at 260 nm/280 nm, and the concentration was determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter). For amplification, an aliquot of 30 ng/μl gDNA was prepared via PCR. Gene-specific primers were designed corresponding to the conserved regions of the nucleotide sequences of Erythrina lectins (accession numbers: FJ8396683.2; AY158072.1; X52782.1) available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore) and then synthesized (Inqaba Biotech, South Africa). PCR amplification was performed in a 25 μl total reaction mixture containing template gDNA (30 ng), 10 μM each of primers (forward: 5′−TGGGGACGTAACAAAAGGAG−3′; reverse: 5′−CTGGCTTGGACTTTGTTGGT−3′), dNTPs (10 mM), MgCl2 (25 mM), Taq polymerase (5 Units/μl; Promega), buffers (5×), and deionized water. The PCR amplification consisted of initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 36 denaturation cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 55°C, and 90 s extension at 56°C in a 96-well Thermal Cycler (Eppendorf Master Cycler Nexus Gradient 230), and a final 4-min extension at 72°C.

Confirmation of PCR products on agarose gel

Amplified products (amplicons) were separated on agarose gel (1% w/v) and stained using ethidium bromide (0.7 μg/ml). Electrophoresis of the PCR amplicons was carried out using a 100-bp DNA ladder (Promega) at 60–90 V for 3 h. The gels were visualized, and the results were monitored using an ultraviolet (UV) transilluminator gel documentation system (Bio Olympics). The amplified product was recovered and purified using a QIA quick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing of the amplified gene

The purified PCR products were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems (ABI) 3500XL automated sequencer using both forward and reverse primers. The cleaned products were injected into the Applied Biosystems ABI 3500XL Genetic Analyser with a 50-cm array, using POP7.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

A homology search of the ESL nucleotide sequence in the GenBank database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST search) was also conducted. Sequence alignment with other plant lectins was analyzed using ClustalW. Nucleotide sequence alignment results were used for phylogenetic analysis using the MEGA7.0 software (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis, version 7.0) program to analyze the evolutionary relationships (Kumar et al., 2016). Integrity of the phylogenetic tree was estimated using 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Results and discussion

Antimicrobial study

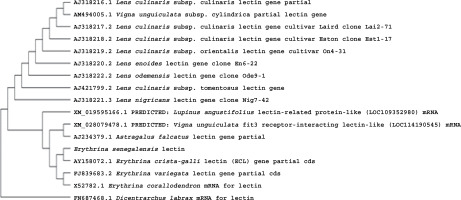

Legumes are rich in bioactive proteins and peptides, including lectins with diverse biological functions, such as playing key defense roles against invading microbial pathogens (Mani-López et al., 2021; Fonseca et al., 2022b). In the present study, homogeneous ESL was obtained via the combination of ammonium sulfate precipitation and column chromatography techniques as reported in our previous study (Kuku et al., 2012). E. senegalensis lectin has an estimated subunit molecular weight of 35 kDa as confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). Konozy et al. (2003, 2012) revealed that the molecular weights of E. lysistemon and E. speciosa lectins were 30 and 26.7 kDa, respectively, after SDS-PAGE analysis, which is consistent with the findings of the present study. Similarly, lectins with an estimated molecular weight range of 26–30 kDa were also detected in Erythrina crista-galli, Erythrina americana, Erythrina flabelliformis, Erythrina lysistemon, Erythrina rubrinerva, and Erythrina vespertilio (Ortega et al., 1990; Bonneil et al., 2004). The range of molecular weight is not surprising as Erythrina lectins are made up of one-chain protomer with a molecular weight of 27–35 kDa that forms a dimer (Osman and Konozy, 2017).

Fig. 1

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis electrophoretogram of Erythrina senegalensis lectin and standard protein markers (15–170 kDa)

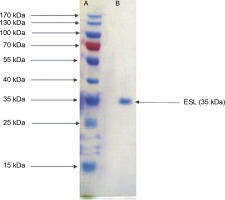

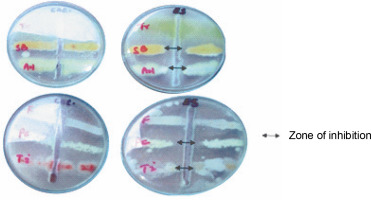

In vitro antibacterial assay showed that ESL significantly (P < 0.05) inhibits the growth of E. carotovora, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus at 0.4 mg/ml, with inhibition zones ranging from 18 to 24 mm (Fig. 2). E. carotovora and S. aureus were most susceptible to the protein, with inhibition zones of 20 ± 0.33 and 24 ± 0.33 mm, respectively (Table 1). However, L. acidophilus was resistant to lectin at this concentration, which suggests that ESL might be devoid of binding affinity to the glycomoieties expressed on the membrane of this organism. The MIC of ESL against susceptible bacteria ranged from 0.05 to 0.2 mg/ml (Table 1).

Table 1

Sensitivity pattern and minimum inhibitory concentration exhibited by Erythrina senegalensis lectin against bacteria isolates

Fig. 2

Plates showing the antibacterial sensitivity of Erwinia senegalensis lectin against Erwinia carotovora (EC), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA), Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA), Klebsiella pneumonia (Kpn), and Staphylococcus aureus (SA)

Lectins have high specificity, enabling them to identify unique sugar structures (Adedoyin et al., 2021). This unique property allows them to mediate specific microbial binding, innate immune response, and cell-to-cell signaling, coupled with host–pathogen interactions (Paiva et al., 2010; Procópio et al., 2017). While eliciting antibacterial activities, plant lectins may cause pore formation, followed by interactions with definite bacterial cell wall components. Potential targets include lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, teichoic and teichuronic acids, as well as muramic- and muramyl-associated structures. These interactions attract extensive interest due to arrays of exposed microbial glycomoieties that are potential lectin-binding sites (Gomes et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2016). In addition, lectins can form aggregates with microbial glycoconjugates, which might block bacteria binding sites, thus preventing host infection (Charungchitrak et al., 2011). Usually associated with their carbohydrate recognition domains (CRDs), antibacterial mechanisms may also include restricting microbial invasion, growth, migration, and competitive inhibition of microbial proteins from specific receptors (Paiva et al., 2010; Breitenbach Barroso Coelho et al., 2018; Monika et al., 2020).

Antibacterial activity exhibited by ESL in the present study was quite impressive as legume lectins were toxic to bacterial pathogens. This is attributable to interactions involving inherent aromatic amino acids and hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl oxygen of sugars and lectin CRD (Dias et al., 2015; El-Araby et al., 2020; Santana et al., 2022). Santana et al. (2022) showed that lectin isolated from the tropical legume Cratylia argentea elicited potent toxicity toward Listeria monocytogenes by reducing its systemic loads. El-Araby et al. (2020) showed that purified lentil and pea lectins inhibited the growth of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, with inhibition zones of 35 and 33.4 mm, respectively, as against 20 and 22 nm manifested by ESL in the present study. As reported by Krishnaveni et al. (2022), lectins from the legumes Cicer arietinum Black (CiarBL) and Prunus dulcis nut raw (PruDuNRL) showed potent antibacterial activity at 100 mg/ml against Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus pyogens, Propionibacterium acnes, and S. aureus. Similarly, lectins from other legumes such as Canavalia ensiformis, Trigonella foenumgraecum, Arachis hypogaea, Cajanus cajan, Pisum sativum, and Phaseolus vulgaris inhibited Streptococcus mutans-induced biofilm formation, supporting the antibacterial properties of these quintessential bioactive proteins (Islam et al., 2012; Lagarda-Diaz et al., 2017).

ESL antibacterial activity reported in the present study compared favorably with the results of specific classical antimicrobials including streptomycin, kasugamycin, chloramphenicol, and oxytetracycline, against pathogenic bacteria: S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, K. pneumonia, Erwinia amylovora, P. aeruginosa, Proteus vulgaris, Hafnia alvei, Serratia marcescens, S. aureus, and Micrococcus luteus (Ulagesan and Kim 2018; Al-esnawy et al., 2021; Slack et al., 2021).

Findings of the present study showed that ESL significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited the hyphal growth of A. niger, P. camemberti, and S. brevicaulis at 0.4 mg/ml, with inhibition zones ranging between 18 and 19 mm (Fig. 3). The MIC obtained for the susceptible fungi ranged between 0.2 and 0.4 mg/ml. The hyphal growth of S. brevicaulis was most inhibited by ESL with an inhibition zone of 19 ± 0.76 mm (Fig. 3). However, T. interdigitale and Trichoderma spp. were resistant to lectin at this concentration (Table 2). This is not surprising as legume lectins are reported to be moderate antifungals (Ynalvez et al., 2021). The growth inhibitory activities of lectins vary between fungal species; however, their mechanism of action is poorly understood (Yan et al., 2005; Araújo et al., 2010; Lam and Ng, 2011; Del Rio et al., 2020). This is because plant lectins cannot suppress fungal growth directly since they do not penetrate the cell wall or cell membrane to reach the cytoplasm (Lagarda-Diaz et al., 2017). Despite this, indirect responses induced by lectin’s attachment to key carbohydrate structures on the fungal surface have been observed in fungal survival (Wong et al., 2010). These structural targets include fungal cell wall chitin components. Specific interactions might result in the inhibition of cell wall synthesis, dissolution of the fungal cell wall, or cell metastasis, resulting in cell death (Lam and Ng, 2011; Breitenbach Barroso Coelho et al., 2018). Similarly, they can also associate with fungal hyphae, suppressing growth because of poor nutrient absorption and spore germination or predisposing the target organism to a certain stress condition by inducing detrimental morphological changes that ultimately lead to cell death (Van Parijs et al., 1991; El-Araby et al., 2020).

Table 2

The sensitivity pattern and minimum inhibitory concentration exhibited by Erythrina senegalensis lectin against fungal isolates

Fig. 3

Plate showing the antifungal sensitivity of Erythrina senegalensis lectin against Aspergillus niger (AN), Fusarium species (F), Penicillium camemberti (PC), Scopulariopsis brevicaulis (SB), Trichophyton interdigitale (Ti), and Trichoderma species (Tr)

Consistent with the present findings, Sitohy et al. (2007) and Devi et al. (2013) reported that at 100 mg/ml lectins isolated from P. sativum and Pongamia glabra inhibited the growth of Candida albicans, Aspergillus flavus, Trichoderma viride, and Fusarium oxysporum. Yan et al. (2005) showed that a lactose-specific lectin from the legume Astragalus mongholicus also inhibited the growth of Botrytis cincerea, F. oxysporum, Colletotrichum spp., and Drechslera turcica at a concentration range of 100–200 μg. Plant lectins have also been reported to cause lethal hypersensitivity reactions by triggering specific cytokines while mediating their antifungal activity (Kanzaki et al., 2008). Similar to ESL, polymyxin, a peptide-based antifungal, has been reported to inhibit the growth of C. albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Fusarium spp. (Hsu et al., 2017).

Corresponding bioactivities of ESL have also been reported in lactose-binding lectins from Chondrilla caribensis and Bufo arenarum (Sánchez Riera et al., 2003; Marques et al., 2018). This suggests that the antibacterial and antifungal activities of ESL might be related to its sugar specificity, as legume lectins are emerging as promising molecules for designing novel therapeutics (Barbosa et al., 2021).

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

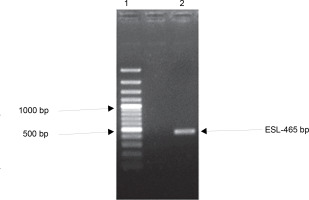

Many plant families contain homologous proteins, such as lectins, that have a common biological function but different specificity toward substrates (Kalinina et al., 2004). This is observed in the complexity of lectin gene organization as variations exist between species. Available data on legume lectin structures suggest that they are closely related proteins (Rougé and Risler, 1990). Furthermore, their homology also indicates that they are well conserved during evolution (Sparvoli et al., 2001; Lioi et al., 2003). To investigate the evolutionary relationship of ESL with other plant lectins, a comparative analysis of the ESL gene was carried out with plant lectin families in a phylogenetic framework. gDNA of E. senegalensis seed was extracted. The gene encoding ESL was isolated using specific primers and analyzed using the BLAST. One set of primers detected the lectincoding gene of E. senegalensis (ESL) via direct PCR analysis. Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products revealed a distinct amplicon fragment (Fig. 4). The lectin gene after Sangers sequencing showed a 465-bp consensus sequence designated as ESL-465.

Fig. 4

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the polymerase chain reaction amplification product of Erythrina senegalensis lectin gene. Standard 100-bp DNA ladder (Lane 1) and amplified ESL-465 (Lane 2)

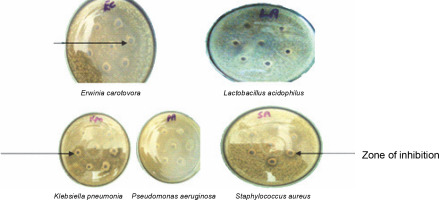

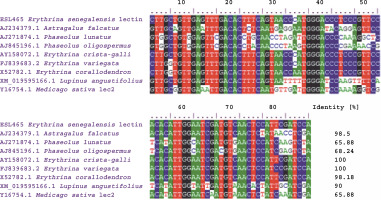

The creation of a multiple-sequence alignment maximizes the chance of positional homology between nucleotides or amino acids by establishing gaps in the evolutionary comparisons of primary sequence data (Talavera and Castresana 2007). BLAST analysis of the ESL-465 nucleotide sequence against nucleotide sequences of plant lectins available in the NCBI database resulted in a significant alignment at 100% nucleotide identity with Erythrina variegata lectin (accession number: FJ839683.2), 100% nucleotide identity with E. crista-galli lectin (accession number: AY158072.1), and 98.18% nucleotide identity with Erythrina corallodendron lectin (accession number: X52782.1) (Fig. 5). This suggests that the lectin gene might be conserved within the Erythrina genus. Analysis of sequence variations or similarities provides insights into their structural divergence and evolution (Williams and Lovell, 2009). Findings of the present study also showed a profound nucleotide alignment at 98.5, 68.24, and 65.88% nucleotide identity with Astragalus falcatus, Phaseolus oligospermus, and Phaseolus lunatus lectin genes, respectively. Although information regarding the bioactivity of lectins from A. falcatus, P. lunatus, P. oligospermus, E. cristagalli, E. variegata, and E. corallodendron is scarce in the literature, the high sequence homology reported for these proteins with ESL might suggest their potential antimicrobial activities. The translation of the ESL-465 nucleotide sequence to the amino acid sequence resulted in a sequence of 134 amino acids (Table 3), which is within the amino acid composition range of legume lectins (Osman and Konozy, 2017).

Table 3

Translated amino acid sequence of ESL465 gene

| ESL00A-465 | |

|---|---|

| Translated amino acid sequence (134 amino acids) | WGRNKRRVWGFTTHQDSKWHAGLGLNGPNSIYTCAHLGDHRHRQLNEILLFHTTLF HTTLHTPTPRWFSILYGTNKQVQQSPSQLKVMDTSEYSTTQNRITHTKHLLLSLTLSV THGTLPRFHTLESMSTPFDP |

Fig. 5

Multiple-sequence alignment of Erythrina senegalensis lectin nucleotide sequence with related plant lectin genes

Recently, functional and structural analysis of individual proteins is becoming more practical via phylogenetic analysis (Song et al., 2018). To elucidate the gene structure and construction of the gene family, nucleotide and/or amino acid sequences can be used. This makes the knowledge of protein sequences in predicting evolutionary relationships acceptable, suggesting that proteins of the same family might, to a greater extent, exhibit similar biological activities (Dey and Meyer, 2015; Xie et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; He, et al., 2017). By multiple-sequence alignment using Clustal W, the evolutionary relationship between the E. senegalensis gene (ESL-465) and other plant lectins was revealed (Fig. 6). The analysis revealed that ESL-465 formed a cluster with other lectin genes from different leguminous families. This is not surprising as legume lectins are uniquely closely related homologous proteins, which are well conserved during evolution (Lioi et al., 2006; Lagarda-Diaz et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Several studies reported that lectins from the Leguminosae family have unique bioactivities, including toxicity toward pathogenic bacteria and fungi. In this study, E. senegalensis seed lectin elicited impressive antimicrobial activity against E. carotovora, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, S. aureus, A. niger, P. camemberti, and S. brevicaulis. The phylogenetic analysis of the ESL gene also showed its evolutionary relationship with other plant lectins (mostly legumes), suggesting the potential antimicrobial activities of these lectins. However, further research on the antimicrobial and structural properties of these lectins is needed to confirm these findings. Furthermore, lectin can serve as a potential target for developing practical applications in agriculture, health, and even pharmaceutical research.