INTRODUCTION

Aggressive behaviour towards medical staff poses a serious problem in the functioning of a psychiatric ward. The literature on the subject defines aggressive behaviour as verbal, non-verbal responses that negatively affects medical personnel or causes property damage in a medical institution [1]. The consequences of aggressive behaviour can vary. They affect different areas of functioning and, as a result, the victim may suffer bodily or psychological injuries. From an economic point of view, the effect of aggression is an increase in financial outlays related to factors such as absenteeism, the need to pay pensions, or the purchase of new equipment [2].

Studies conducted in many countries show similar results – in 9-24% of cases, staff most often encountered verbal aggression, while in 5-21% of cases, they experienced psychological aggression. Research results also show that during the 12 months of work, nurses experienced violence more often than physicians. A&Es and psychiatric wards are where aggressive incidents by patients and their families are most frequent [1].

Aggressive behaviour may result not only from the actions of the patient themselves, but also from the way the staff interact with the patient or from the rules of the facility. Even in situations assessed as objectively non-threatening, the accumulation of specific factors may result in aggressive behaviour [3].

Aggressive behaviour has a negative impact on mental health in staff as it may lower self-esteem, self-confidence, or readiness to act [4]. The first emotional reaction is usually anger, fear (anxiety), and helplessness [5]. The anxious attitude reinforces avoidance and withdrawal from duties, decreased productivity, and ultimately it may lead to burnout or resignation from further career as a healthcare professional. Moreover, patient aggression may evoke a variety of emotions among employees that are linked to their personal experience, which often has a negative impact on the therapeutic relationship [6].

The aim of the study was to analyse the incidence of aggressive behaviour in patients of Adolescent Psychiatric Wards in Poland during a 5-year period towards physicians and nursing personnel and to assess the usefulness of the tools selected by the authors to describe the incident itself. Currently, Polish literature and practice lack such scales.

METHODS

The tool used in the study was the Staff Observation Aggression Scale – Revised (SOAS-R). It is an instrument used to describe aggressive incidents on hospital wards. Since its introduction, SOAS has been used as a measurement tool in many descriptive studies and in analysing the effects of aggressive incidents on psychiatric wards [7]. It is a popular tool used in many countries, both in research and practice [8, 9]. Currently, it is most commonly used in geriatrics and on A&E wards [10-12]. The Polish version of the SOAS-R was created with the consent of the tool’s authors and has been approved by them.

The SOAS-R questionnaire is completed by only a member of staff who has experienced or witnessed aggressive behaviour. The questionnaire consists of two pages, with the cause, object of aggression, goal, actions taken, and its consequences specified. There is also a place for a short description of aggressive behaviour, place of incident, presence of witnesses to the aggression, and signals that might have indicated the possibility of aggressive behaviour [7, 9]. The sheet also includes questions about the number of staff present, warning signs, and potential self-harm incidents. An additional element of the tool is the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) measuring the subjective sense of threat of the examined staff member [13]. To obtain quantitative variables, the method suggested by the authors of the tool was used to convert the results depending on the VAS scale, assuming the conversion of a visual scale to numerical one (from 0 to 10).

The data are a result of preliminary assessment of the scale’s usefulness in the description of aggressive incidents on the adolescent psychiatric ward and are part of the process of adapting the tool to Polish conditions.

The study used the results of 71 questionnaires completed by the staff of the adolescent inpatient psychiatric ward in the period from August 2015 to August 2019. The questionnaires did not include data that would enable the identification of persons involved in the aggression incident. The ward staff were asked to fill in the questionnaires immediately after each adverse event. The questionnaire was to be completed by one of the medical staff involved in the incident.

The analysed inpatient psychiatric ward dedicated to adolescents has been operating since 1968. During the study period, it initially had 20 beds, later bringing the number to 32 (as of April 2018). Many incidents of aggression, i.e., between patients, went unreported. To estimate the scale of the issue, we relied on bed occupancy data during the study period. Details of hospitalisations during the study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Specificity of hospitalizations during the research period

The data were analysed using a combination of descriptive and inferential statistical methods. Chi-square tests were conducted to evaluate differences in responses between doctors and nurses, assessing whether the two groups varied significantly in their approaches to managing aggression and recognising early indicators of aggressive behaviour.

To explore the relationship between the time of the day and the severity of aggressive incidents, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was applied. Given the variation in severity ratings between physicians and nursing staff, correlations were also analysed separately within each group. Temporal patterns were examined by comparing the hours during which incidents occurred to those without incidents using the Mann-Whitney U test. Additionally, staffing adequacy was evaluated across different time periods to identify any variations in staffing levels throughout the day.

RESULTS

The analysis included cases of aggressive behaviour displayed by patients during hospitalisation on the ward.

The absence of standardised procedures for recording aggressive behaviour has made it impossible to determine the total number of such incidents throughout the study. We have 71 sheets for 63 episodes. In 7 cases, the questionnaires were completed by more than one staff member. Seventeen cases were recorded in the SOAS-R, following the use of direct coercion as a consequence of aggressive behaviour: 3 cases of patient isolation, 13 cases of four-point restraint of the patient with magnetic straps, 1 unspecified “direct coercion”.

Nursing staff completed 66% of the questionnaires and physicians – 34%. In 18 cases, the questionnaire was filled in only by a doctor. In 37 cases – by the nursing staff alone. In 13 cases – by members of both professions.

The most frequent object of aggression on the ward was the medical staff (57.8%); self-harm was less frequent (4.6%). Other patients (7.1%) or objects (16.2%) were relatively rarely the victims.

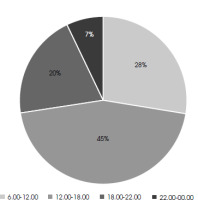

The diagram below shows the number of aggressive episodes at particular times of the day. To improve readability, the hours corresponding to the aggressive cases were grouped into intervals (Figure I).

The analysis of the time of the day of aggression showed that the biggest number, i.e., 45% of aggressive behaviours, was recorded in the afternoon between 12:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. On the other hand, 28% of aggressive behaviours was registered between 6:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m., 27% between 6:00 p.m. and 12:00 a.m., 0% between 12:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m.

Using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, average- strength relationship (r = 0.40) was found between the scale of aggressiveness and the time of incidence, at the significance level of α = 0.04. The later the aggressive behaviour occurred, the higher the assessed aggressiveness of the perpetrator.

The most common form of aggression was using hands (punches, blows); it was reported in 80% of aggressive acts. It turned out that half of the incidences of aggressive behaviour using hands (punches, blows) took place between 2:00 p.m. and 8:30 p.m., α = 0.02.

Verbal aggression was involved in 42% of reported incidents, but incidents of verbal aggression alone accounted for only 5.6%. According to staff assessments, most aggression incidents (42.6%) occurred without any provocation that the staff could recognise or understand.

The following reasons were indicated: refusal of something (17%); other (13%); help with patient’s everyday activities (10%); staff’s attempt at medication administration (10%); other patient(s) (1%). Other reasons included nurse entering the isolation room, holding the patient during their strangulation attempt, securing the patient, communicating the need to use direct coercion, asking the patient to hand over their cigarettes and lighter, taking blood, placing a stomach probe, admission to the ward.

What turned out to be interesting, although statistically insignificant, was the dependence of the types of provocation on the time of the day, i.e., 50% of incidents with “no understandable provocation” took place between 12:45 p.m. and 4:30 p.m. In the afternoon, after 5:00 p.m., there was a relationship between aggression and helping the patient in everyday activities, as was aggression preceded by a provocation described as “other provocations” – all occurred after 12:45 p.m., half of which between around 4:00 p.m. and 9:30 p.m. The provocation described as “refusal of something” took place earlier than 2:00 p.m.

The most common actions taken by staff during an aggressive incident were the following: talking to the patient (59%), mechanical restraint (direct coercion in the form of restraint using magnetic straps) (44%), physical restraint – holding (40%), calm departure (30%), other measures (27%), parenteral drug administration (20%), seclusion (20%), oral drug administration (14%). A calm departure from the patient displaying aggressive behaviour was most often used in the early afternoon hours, usually between 12:30 p.m. and 2:15 p.m., significance level α = 0.01. The personnel’s actions described in the survey as “mechanical restraint” took place in the afternoon and evening hours, and half of them fell within the time interval between 2:20 p.m. and 9:15 p.m., significance level α = 0.01.

The analyses of the personnel involved in solving the aggressive situation showed several dependencies. “Physical restraint” as an action to stop aggression was undertaken twice as often by doctors than by nurses (Table 2). The relatively frequent observance of warning signs by doctors is noticeable. Most doctors could see them (9 out of 11), while more than half of the nurses could not (10 out of 18) – average relationship at the significance level of α = 0.05 (Table 2).

Table 2

Differences in actions between doctors and nurses

| Staff member | Answer | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Taking action to stop aggression: physical restraint (holding) | |||

| Nurse | 16 | 4 | 0.01 |

| Doctor | 5 | 8 | |

| Seeing warning signs | |||

| Nurse | 10 | 8 | 0.05 |

| Doctor | 2 | 9 | |

In the Spearman-Rank correlation analysis, a moderate positive relationship was observed between aggressiveness and the hour of occurrence, with a correlation coefficient of 0.40 and a significance level of 0.04, indicating that higher aggression ratings were associated with later hours. When examining the correlation by professional groups, physicians showed a stronger correlation (r = 0.59, α = 0.06), while nurses exhibited a weaker correlation (r = 0.16, α = 0.50).

According to the respondents’ assessment, the number of staff members present during the aggressive incident was insufficient, mainly after 2:30 p.m.; relationship at the significance level α = 0.02.

DISCUSSION

The obtained results confirm previous studies indicating that health care workers are an occupational group that is particularly exposed to acts of aggressive behaviour at work [1]. As many as 84% of aggression cases were targeted at the employees. Unfortunately, many instances of aggression between patients went unreported, often due to staff’s lack of awareness about their occurrence. This issue requires further investigation.

The questionnaires filled in by the staff mentioned aggression using hands (punches and blows) as the most common form of aggression. Verbal aggression accompanied aggressive behaviour in 26 cases, and it appeared as an isolated form of aggression in 4 cases. Clinical experience shows that verbal aggression is more common. The analysed result may be related to the fact that verbal aggression is so frequent on adolescent wards that it is not reported by the staff. This does not mean, however, that it does not affect employees.

The study suggests that aggressive episodes may be influenced by the time of the day and the type of staff involved, distinguishing between physicians and nursing staff. Dependence on the time of the day may be related to the number of staff on the ward. Until 3:00 p.m., there are doctors, occupational therapists, educators, psychotherapists, and nurses – the total number of employees is around 25 people. After 3:00 p.m., the number of staff decreases noticeably, with only one doctor on duty and three nurses. In the analysed incidents, physicians much more often observed warning signs of possible incidence of aggressive behaviour. One possible interpretation is that doctors may find it easier to spot signals predisposing to aggression or because doctors are often called to attend to patients already exhibiting crisis behaviours, which could heighten their focus on warning signals. The disparity may also result from differences in the training of physicians and nurses. Earlier studies showed that nurses are the most common victims of aggressive incidents [2, 3]. There is also a social stereotype that aggressive behaviour towards nursing staff leads to less consequences. These factors suggest that nursing staff face a particularly heavy workload in the afternoon. An emotional difficulty in working in psychiatry, especially for nursing staff, lies in the unpredictability of patient aggression.

The data included in the questionnaire do not allow the gender identification of particular staff members, but it is worth noting that there is a significant prevalence of women among the employed nursing staff, as opposed to the distribution of 50/50 women to men among physicians. It may be one of the factors that make nursing staff consider aggressive patient behaviour more threatening. The issue of the importance of gender of both the perpetrator and the victim for the assessment of aggression intensity on psychiatric wards requires further analysis. The same gender of the perpetrator and the victim may also influence the escalation [14].

The consequences of the acts of aggression for the personnel of the examined ward are also different. Most often, it resulted in the victim of the attack feeling unsafe, which had also been indicated by previous research. Experiencing such emotions and their consequences had been shown in previous studies [15]. Meeting aggressive behaviour leads to many negative consequences, one of the most serious of which is the burnout syndrome. In addition, being confronted with aggression may lead to a decision to quit one’s job. It also has negative consequences for the quality of healthcare when an experienced and educated member of medical staff leaves their job.

Our study has many limitations. The number of questionnaires does not correspond to the number of self- aggressive and aggressive behaviours on the ward because completing the questionnaire was voluntary and did not constitute part of the hospital procedure. It could be omitted especially when filling in the documents for the use of direct coercion. The analysis of interactions between reported aggressive behaviour and the use of restraint and reporting of adverse events will be the subject of further analyses.

The term “mechanical restraint” used in the questionnaire was interpreted in various ways by the respondents, most often understood as the use of direct coercion in the form of four-point restraint.

Seven episodes of aggression were assessed by different people. However, they were included in all the material as they referred to various moments in the dynamics of aggressive behaviour development and each time described the respondent’s direct involvement in the event. It also demonstrates the need to decide to what extent the questionnaires assess the more isolated experience of interaction with an aggressive patient and to what extent they exhaustively describe the overall event. The situations where we deal with escalating aggressive behaviour towards personnel may point indirectly to the failure to apply sufficient coercive measures in the form of isolation or immobilisation. The dynamics of interactions on psychiatric wards for adolescents is not included in the survey; however, it is extremely important in the operations of an adolescent ward and has not been the subject of sufficient scientific reflection for a long time [16]. In our opinion, interactions within the peer group are of key importance in understanding aggression on the ward. Mature attitudes of some members of the therapeutic community may influence the behaviour of others. We can also deal with a situation in which group dynamics provoke aggressive and self-aggressive behaviour. In the analysed period, we observed joint or mutually provoked episodes of self-harm, attacks on personnel, interrelated sequential behaviours or suicide attempts. However, the survey we used in the study does not analyse the complex interactions within the ward and the effect they have on aggressive and self-aggressive behaviour.

The most common action taken in response to an aggressive incident was a conversation with the patient (59%). One may wonder to what extent the way of reacting to aggression can strengthen it by means of instrumental conditioning. The techniques of dealing with self-harm resulting from dialectical behaviour therapy indicate the unfavourable consequences of starting a conversation with the patient immediately after the episode of self-harm [17, 18]. However, we wonder if a conversation following an act of aggression could have a similar reinforcing effect?

We have learnt from interviews, staff briefings, and supervision that there are staff members who are better at dealing with escalating aggressive behaviour and others who are not. As a result, the therapists’ team see certain shifts as burdened with a greater risk, while others – with a lower risk of aggressive behaviour. This issue undoubtedly requires in-depth scientific and practical reflection. Techniques and principles of dealing with an aggressive patient should be part of the therapeutic culture of the ward, as well as the subject of reflection and supervision. However, this aspect usually remains underestimated in Polish psychiatry, and the training is limited to the rules of using direct coercion and is of the nature of peer-to-peer learning.

What is worth mentioning here is the gross disproportion in the ratios of nurses to individual patients in Poland. In the case of psychiatric wards, it is 0.6 nurses per patient, and in the case of paediatric wards – 0.8 nurses per patient [19].

The results of our study show the need for decision- makers to realise that the risk of serious problems or even death, both for patients and staff on adolescent psychiatric wards, requires similar care to the professional treatment on paediatric wards. Especially since on paediatric wards, children are often hospitalised with their parents, which is rare on psychiatric wards.

In the period covered by the study, we also observe changes in the psychopathology of patients admitted to the ward. There has been an increase in the number of hospitalisations of patients diagnosed with behavioural and emotional disorders, greater instability in the care situation of patients, as well as a bigger number of suicide attempts and self-harm incidents [19]. The vast majority of circumstances in which patients are admitted to a psychiatric ward are dictated by a crisis situation. Most admissions to the analysed wards were emergency admissions (and not a planned one). They amounted to 83% of hospitalisations in 2015, 87% in 2016, 84% in 2017, 77.5% in 2018, and 72% in 2019. It should be noted here that planned patients are usually people waiting for a place in hospital after an urgent on-duty consultation. In the period covered by the study, such analyses were not carried out, but there are many indications that a significant percentage of patients hospitalised on the ward are patients with a forming borderline personality – it is indicated by studies [20] which say that borderline personality traits are found in 78% of adolescent patients with suicidal thoughts and tendencies who report to emergency rooms. In this context, aggressive and auto-aggressive behaviours may also be an element of the countertransference relationships formed between patients or the patients’ relationships with the team due to difficult or traumatic life experiences of patients and complicated relationships with their caregivers. This also means that the understanding of individual behaviours sometimes indicates the expression of emotional regulation, the relational strategy of behaviour, and other times it reflects deep traumas [21].

Regardless of the doubts, this study highlights the importance of aggression analyses on adolescent psychiatric wards. When deciding to work in a psychiatric unit, including adolescent psychiatry wards, one must consider that they may become a victim of aggression. Preventing aggression and dealing with its incidence must be included in the organisation of work on the ward.

CONCLUSIONS

The study aligns with existing literature the problem of aggressive behaviour on psychiatric wards. It demonstrates the need to educate medical personnel in the field of reducing emotional tension through proper communication. The ability to establish a relationship with an agitated patient and to de-escalate emotions at an early stage is the basis for the prevention of physical aggression and violence.

Communication skills also apply to post-incident management. Among the consequences of aggression, the respondents emphasised that in addition to the need for medical assistance, psychological support was also needed. It therefore seems that an important element of the procedure should be to allow staff members to recover from strong emotions they may experience because of aggressive patient behaviour.

The research also identified several practical implications. SOAS-R can potentially be a tool in incident assessment, both at the level of causes and, what seems most important, the consequences of aggressive behaviour. It seems that this problem is often unduly underestimated, whereas it is one of the reasons for the outflow of experienced personnel from the healthcare sector. SOAS-R can also be used for analysis of staffing at particular times of the day, week, or even month. However, the phenomenon of aggression requires a more precise, regular, and spread-over analysis. Only such approach will facilitate the implementation of appropriate procedures and the overcoming of several stereotypes related to aggressive behaviour and its impact on the relationship between physicians and nursing staff and the patient.

In some cases, the SOAS-R can be a practical alternative for introducing discussions about problems on the ward’s everyday operations, enabling an accurate and quick description of an aggressive incident. At the same time, it makes it possible to conduct adequate analyses of the situation on the ward and the scale of incidents. However, the staff must be willing to change their mentality and ready to fill in a document that they see as supplementary.

Analyses of specific events indicate that the provisions on the use of direct coercion in the Mental Health Protection Act are not adequate for the practice on adolescent psychiatric wards. Acts of violence often occur without warning, particularly in special cases where patients are at a constant risk of agitation or aggression, such as those with intellectual disability or autism. In these situations, the necessity to use one of the forms of coercion may not always result from an immediate danger but rather from the patient’s behavioural profile, where the risk of aggression is continuous.