Introduction

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare, potentially life-threatening disease characterized by recurrent attacks of swelling caused by bradykinin accumulation in tissues. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, but 25% of patients have a de novo mutation [1]. Attacks frequently affect the extremities, face, oropharynx, gastrointestinal system and genitalia and are unresponsive to antihistamines, corticosteroids, or epinephrine [1]. Oropharyngeal involvement, which can lead to asphyxiation, is particularly concerning [1, 2–5]. HAE is classified into HAE with C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency (HAE-1, type 1, 85%), HAE due to C1-INH dysfunction (HAE-2, type 2, 15%), and normal C1-INH HAE, which is rare [1, 6].

The main purpose of HAE treatment is to provide disease control. Disease control is possible by preventing attacks and ensuring the quality of life of patients [1, 7]. According to the World Allergy Organization/European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (WAO/EAACI) recommendations, all patients should be educated about potential triggers and taught how to self-administer on-demand treatments. Attacks should be treated early and short-term prophylaxis (STP) should be considered before potential angioedema-inducing events such as medical, dental or surgical procedures. Long-term prophylaxis (LTP) should be evaluated based on disease activity, burden, control, and patient preferences, and all patients should have an action plan. Patients on LTP should be routinely monitored to optimize treatment [1]. Comprehensive education for patients and their families about triggers and attack management, family screening, and detailed information about the disease are crucial to prevent disease-related morbidity and mortality [1].

Environmental factors, physical trauma, dental and medical procedures, fatigue, infections, menstrual-related changes, emotional stress, and drugs affecting bradykinin metabolism (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives, oestrogen hormone replacement therapy) are significant potential triggers, though attacks can also occur without an identifiable trigger [1, 8–10]. Studies have shown that patients can often identify prodromal symptoms – both subjective and objective signals (e.g., fatigue, irritability, discomfort, tension, pain, itching/tingling, erythema marginatum) – prior to an attack, enabling them to predict impending episodes [1, 11–14].

Although HAE is considered a rare disease worldwide, it is not uncommon in the region where our clinic is located, particularly due to sociocultural characteristics.

Aim

The aim of our study is to evaluate the prodromal symptoms, attack triggers, and treatment attitudes of our HAE patients followed in our clinic, in order to establish strategic goals to improve disease control and enhance the quality of life for our patients.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

According to the latest guideline from the WAO/EAACI [1], the study included patients aged 18 and older who had been diagnosed with HAE and were monitored in our Allergy-Immunology Clinic between 2022 and 2023. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (approval number: 29), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards.

Data collection

During each routine (scheduled monthly follow-ups) and non-routine (unscheduled visits due to attacks) clinical visit, patients were routinely evaluated by us regarding the nature of their attacks, prodromal symptoms, and potential triggers. Information about potential triggers and the use of LTP was provided, and these details were recorded in patient files. Study-related data (patient demographic characteristics, age at symptom onset, age at diagnosis, year of delay in diagnosis, HAE subtype, C4 and C1 inhibitor levels, presence of prodromal symptoms, factors triggering attacks, type and monthly frequency of attacks, hospital admissions, number of attacks management, laryngeal attack history, responses to attack treatment and knowledge about triggers, on-demand therapy agents, knowledge about situations requiring STP, knowledge about contraindicated drugs, attitudes towards LTP use) were obtained by scanning retrospective patient files.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included individuals aged 18 and over diagnosed with HAE who attended the Allergy-Immunology Clinic during the specified period and whose medical records were accessible. Patients whose records could not be retrieved were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

All data for this study were analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 28. Descriptive statistics were presented as frequency and percentage for categorical variables and as median (minimum-maximum) values for continuous variables. Comparisons between independent groups for categorical data were performed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. The suitability of continuous variables for normal distribution was examined using both analytical methods (Kolmogorov-Smirnov/Shapiro-Wilk tests) and visual (probability plots and histograms). Non-parametric comparisons of continuous variables across two independent groups were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlation between two continuous variables, at least one of which did not show a normal distribution, was analysed using the Spearman correlation test. A type-1 error level below 5% was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

The study encompassed a total of 23 patients (14 (60.9%) females and 9 (39.1%) males) with a mean age of 34.74 ±11.80 years. Consanguineous marriage was present in 2 (8.7%) patients, a family history of HAE was noted in 22 (95.7%) patients, and a history of HAE-related deaths in family members was reported in 17 (73.9%) patients. Of the 44 individuals in the family from the same great-grandfather, 24 were diagnosed with HAE and 15/24 were under follow-up in our clinic. This family was the largest family in our study (Supplementary Figure S1).

Eleven patients were primary school graduates, seven were high school graduates, four were university graduates, and one patient was illiterate. Ten (43.4%) patients were employed. The median age of symptom onset was 15 years (range: 4–26), the median age at diagnosis was 20 years (range: 11–-60), and the median duration of diagnosis delay was 9 years (range: 0–50). A significant positive correlation was found between patient age and duration of diagnosis delay (r = 0.575; p = 0.004) (Figure 1).

The median serum C4 complement level of the patients at diagnosis was 3 milligram/decilitre (mg/dl) (range: 1–11) (laboratory reference: 10–40 mg/dl), and the median serum C1-INH level at diagnosis was 8 mg/dl (range: 2–14) (laboratory reference: 16–33 mg/dl). All patients had HAE-1. Seventeen (73.9%) patients were diagnosed by adult allergy and immunology specialists, five were diagnosed by paediatric allergy and immunology specialists, and one was diagnosed by a gastroenterologist. All patients were regularly followed up in adult allergy and immunology clinics. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1.

Table 1

The demographics, clinical characteristics, knowledge and awareness of the study group

Comorbidities, knowledge and awareness

Nine (39.1%) patients had comorbidities; three were being followed by a psychiatrist for anxiety, and one was being followed by a rheumatologist for familial Mediterranean fever. Seventy percent (n = 16/23, 69.6%) of the patients knew the drug groups contraindicated (e.g., ACEi, oestrogen hormone replacement therapy) for use in HAE, and 91.3% knew the procedures for which they should receive STP (e.g., endoscopy, colonoscopy, intubation, dental, and surgical procedures). Although 91.3% of the patients knew that HAE was an autosomal dominant inherited disease, none had received genetic counselling before having children. Detailed comorbidities, knowledge and awareness the patients are given in Table 1.

Symptoms and triggers

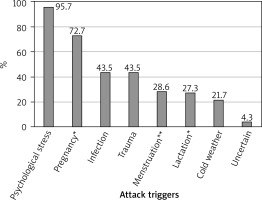

The initial diagnosis was made based on gastrointestinal symptoms in 60.9% (n = 14) of patients, facial involvement in 43.5% (n = 10), and limb involvement in 26.1% (n = 6). A history of laryngeal attacks was present in 69.6% (n = 16) of patients, with 34.8% (n = 8) requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission due to attack severity. The primary triggers of attacks were identified as fatigue and emotional stress in 95.7% (n = 22) of patients, infection in 43.5%, trauma in 43.5%, and exposure to cold in 21.7% (Figure 2, Table 2). Four (28.6%) out of 14 female patients identified their menstrual cycle as a trigger for attacks. Although not statistically significant, all patients who indicated menstrual cycle as an attack trigger had a monthly attack count of over 6 (100% vs. 40%, p = 0.085) (Figure 3). Among the 11 women with a history of pregnancy, 8 (72.7%) reported an increase in attacks during pregnancy, and 3 (27.3%) reported an increase during lactation. Two patients were diagnosed during pregnancy (Table 2).

Table 2

Attack triggers, prodromal symptoms and attack areas of patients

| Parameter | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Attack triggers (n = 23): | |

| Fatigue and emotional stress | 22 (95.7) |

| Infection | 10 (43.5) |

| Trauma | 10 (43.5) |

| Exposure to cold | 5 (21.7) |

| Attack triggers* (n = 14): | |

| Menstrual cycle | 4 (28.6) |

| Attack triggers** (n = 11): | |

| Pregnancy | 8 (72.7) |

| Lactation | 3 (27.3) |

| Prodromal symptoms: | 18 (78.3) |

| Tiredness/fatigue | 9 (39.1) |

| Tingling sensation | 9 (39.1) |

| Erythema marginatum | 7 (30.4) |

| Pressure or tightness in the skin | 4 (17.3) |

| Itching | 1 (4.3) |

| Initial attack areas involvement: | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 14 (60.9) |

| Facial involvement | 10 (43.5) |

| Limb involvement | 6 (26.1) |

| Attack involvements that frequently accompany during follow-up: | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 23 (100) |

| Limb involvement | 20 (86.9) |

| Genital involvement | 4 (17.3) |

| History of laryngeal attack and ICU admission: | |

| Laryngeal attacks | 16 (69.6) |

| ICU admissions | 8 (34.8) |

Figure 2

Our patients’ attack triggers, *Among 11 women with a history of pregnancy, **Among 14 women

The median monthly attack frequency was 6 (range: 1–10), with 11 (49%) patients experiencing more than 6 attacks per month. All patients experienced gastrointestinal attacks during the course of their disease. Following gastrointestinal attacks, the most frequently affected area was the limb involvement, observed in 86.9% (n = 20) of patients, and 4 (17.3%) patients had genital attacks. Eighteen (78.3%) of the patients described prodromal symptoms before the attack. While the most frequently described prodromal symptoms were subjective, such as tiredness/fatigue, tingling, pressure or tightness in the skin, and itching, 30.4% (n = 7) of the patients reported erythema marginatum.

No significant differences were found between patients with and without ICU admissions in terms of gender (p = 0.657), age at diagnosis (p = 0.636), awareness of contraindicated medications (p = 1.000), joint (p = 1.000), gastrointestinal (p = 0.657), or facial involvement at diagnosis (p = 0.221), presence of prodromal symptoms (p = 0.621), median monthly attack count (p = 0.466), or STP use (p = 0.657). Similarly, no significant correlation was found between experiencing more than 6 attacks per month and gender (p = 0.400), age at diagnosis (p = 0.880), awareness of contraindicated medications (p = 1.000), joint (p = 0.371), gastrointestinal (p = 1.000), or facial involvement at diagnosis (p = 0.680), presence of prodromal symptoms (p = 0.317), or STP use (p = 1.000).

Treatment and short- and long-term prophylaxis

All patients knew how to use subcutaneous icatibant for on-demand treatment and used it to manage their attacks. If icatibant was not effective in treating an attack or if there was swelling above the shoulders, they would go to the emergency department to receive intravenous plasma-derived C1 esterase inhibitor (pdC1-INH) concentrate. In 52.2% of patients, the response time to icatibant for on-demand treatment was less than 30 min. The response time to treatment varied depending on the attack location in 63.6% of patients; gastrointestinal involvement typically showed faster response times compared to extremity involvement. The STP and LTP usage rates among the patients were 39.1% and 4.3%, respectively. Nine patients received STP treatment with pdC1-INH concentrate. An attack occurred in one of these patients (after dental treatment). One patient was on danazol treatment for LTP. The patient using danazol was a male university student with no family history of the disease, diagnosed in the gastroenterology department due to gastrointestinal attacks. With danazol treatment, the frequency of attacks was one per month. Three (13%) patients who had previously been on danazol treatment discontinued it due to side effects (elevated liver enzymes, hypertension, and rash).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the attack frequency and associated factors in our HAE patients. Our findings are consistent with many clinical characteristics of HAE reported in the literature. Despite having a high level of awareness about HAE, our patients frequently experienced attacks. This highlights the issue of pharmacophobia, particularly due to the second-line status of accessible LTP medications in our country and their associated side effects.

Although HAE-1/HAE-2 has an autosomal dominant inheritance, approximately 25% of cases occur as a de novo mutation [1, 15, 16]. Only one of our patients had no family history of the disease. Although HAE-1 accounts for approximately 85% of known cases, all of our patients had HAE-1 [6, 15]. We think that these findings are due to the limited number of patients in our cohort. Studies have reported that clinical symptoms in approximately one-third of HAE-1/HAE-2 patients appear by the first 5 years of life and the majority before the age of 20, with only about 4% experiencing their first attack after the age of 40 [17, 18]. The median age of onset of symptoms in our cohort was consistent with literature data.

In the literature, the average diagnostic delay for HAE is reported to be approximately 1.4–8.5 years, with some studies indicating delays of up to 13–20 years [9, 17–20]. Zanichelli et al. have shown that there have been improvements over time in the diagnosis of HAE-1/HAE-2, with patients now being diagnosed at a younger age and experiencing shorter delays between symptom onset and diagnosis [20]. In our study, the median duration of diagnosis delay was 9 years. Consistent with the literature [20, 21], younger patients in our study experienced shorter diagnostic delays (Figure 1). We believe this is due to family screening conducted following the diagnosis of the index case, increased awareness of the disease, and the detailed information provided to patients during follow-ups by allergy-immunology specialists. Diagnostic delays are particularly concerning due to their inadequate management of life-threatening laryngeal oedema attacks and the associated risk of mortality. Approximately 30% of patients have a family history of death due to upper airway obstruction [5, 9, 17]. In our cohort, 73.9% (n = 17) of our patients had a family history of death due to laryngeal attack. The high family mortality history in our cohort may be attributed to the small size of the cohort, and the fact that most of the patients were relatives, suggesting that the positive family history may be recurring.

Studies have reported that approximately half of the patients experience multiple laryngeal oedema attacks throughout their lives. In a study evaluating 55 patients after diagnosis, 19 (34.5%) patients had experienced at least one laryngeal attack, 2 required intubation, and the attacks were more frequent in females (89.5%) [3]. In our study, 69.6% (n = 16) of the patients had experienced at least one laryngeal attack in their lifetime, 30.4% (n = 7) required endotracheal intubation, and 34.8% (n = 8) had a history of ICU admission. Similarly, in our study, laryngeal attacks were more frequent in females (62.5%). We think that the higher number of laryngeal attacks in our patients than reported in the literature is due to the patients’ pharmacophobia against LTP.

The literature states that physical and emotional stress are strong attack triggers [9]. Additionally, common triggers include fatigue, infections, hormonal changes associated with menstruation, and medications that affect bradykinin metabolism [1, 8–10, 22]. All but one patient in our study reported experiencing emotional stress specifically as a potential trigger (Figure 2). This was followed by infections, trauma, exposure to cold, and, in women, menstruation and pregnancy. Additionally, similar to a study in the literature [23], the most common comorbidity in our patients (n = 3, 13%) was anxiety. However, most patients did not have an expert assessment for emotional distress.

Studies have shown a significant correlation between prodromal symptoms and the ability to predict an impending attack [13, 14]. In a study involving 208 HAE patients from the UK (n = 128) and Spain (n = 80), 56% (n = 116) reported experiencing prodromal symptoms before most of their attacks. The most common early symptoms were tiredness/fatigue, pressure or tightness in the skin, and abdominal pressure (64%, 53%, 52%, respectively). Prodromal symptoms typically appeared 2 h before swelling in 40% of patients, 2–6 h before in 27%, and 6 h before in 29%, particularly before gastrointestinal attacks [12]. In our study, most patients reported prodromal symptoms such as tiredness/fatigue (n = 9, 39.1%) and subjective symptoms like tingling (n = 9, 39.1%). Additionally, 30.4% (n = 7) reported erythema marginatum.

According to WAO/EAACI recommendations, all patients should be educated about potential triggers, taught to self-administer on-demand treatments, and evaluated for both STP and LTP [1]. Studies have shown that early treatment of attacks increases response rates [1, 7, 9]. All our patients, regardless of their educational background, were knowledgeable about potential triggers, including contraindicated drug groups, and had access to and administration of on-demand icatibant therapy. With this treatment, the response time to most attacks of patients was below 30 min, consistent with the literature [9, 24]. STP with pdC1-INH concentrate is recommended for patients with HAE. Additionally, due to the possibility of attacks despite STP, follow-up and access to on-demand treatment are recommended [1, 7]. Nine patients had a history of STP with pdC1-INH concentrate. An attack developed during follow-up in 1 patient who underwent STP. The attack rate after STP treatment was found to be similar to those reported in the literature (11.1% vs. 12.5%) [25, 26].

According to WAO/EAACI recommendations, each patient should be evaluated for LTP based on disease activity, burden, control, and patient preferences, with routine optimization and monitoring of treatment [1]. pdC1-INH concentrate, berotralstat, and lanadelumab are recommended as first-line LTP. Androgens are recommended only as second-line LTP and should only be used if first-line LTP agents are unavailable. Antifibrinolytics (tranexamic acid) are not recommended for LTP. If first-line LTP agents are inaccessible and the use of attenuated androgens is contraindicated, tranexamic acid may be used. However, if second-line LTP is used, close follow-up is recommended due to the risk of inadequate attack control and possible side effects [1].

Currently, second-line agents are used for LTP in our country due to the unavailability of first-line LTP agents. In our cohort, one patient was on danazol treatment for LTP. This patient, a male university student with no family history of the disease, was diagnosed in the gastroenterology department due to gastrointestinal attacks. Under danazol treatment, his attack frequency was approximately once a month. Attenuated androgens have been used for LTP for a significant duration. They are advantageous due to oral administration and high efficacy, with an average attack reduction of 83% [27]. However, a range of dose-dependent side effects can occur during LTP [7]. In our study, 3 (13%) patients discontinued danazol due to side effects. Despite having a family history of HAE-related deaths and frequent attacks, pharmacophobia towards second-line LTP agents was prevalent due to side effect concerns, information provided before treatment, and close community ties.

Pharmacophobia is defined as the fear of pharmacological treatments, which can negatively impact patient compliance, leading to incomplete or inadequate treatment, disease relapses, and a decreased quality of life [28]. Although the exact causes of pharmacophobia are not yet fully understood, studies suggest they are multifactorial, arising from the interaction of elements such as the healthcare system, disease status, therapeutic agents, and individual patient characteristics [28–30]. Patient involvement in the prescription process, careful drug selection, and education about potential side effects are emphasized as strategies to manage pharmacophobia [28–31]. However, in our study population, despite providing patients with comprehensive information about the course of HAE, offering detailed explanations of drug side effects, and explaining that treatment with second-line LTP would begin at a low dose with close monitoring and gradual titration, pharmacophobia persisted. To our knowledge, there is no existing literature specifically addressing pharmacophobia in HAE patients, and our experience with HAE patients suggests that these strategies alone may not be sufficient. Therefore, more comprehensive research on pharmacophobia, particularly studies focused on the HAE population, may be crucial for optimizing treatment approaches in rare diseases like HAE.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective study, there is a potential for recall bias in the data collection process. Detailed information regarding pregnancy and lactation as triggers for attacks, as well as specifics of STP during pregnancy/labour, were not fully accessible due to the retrospective nature of the study. Therefore, we believe that prospective studies designed to provide more accurate and objective information (e.g., diaries or applications for patients to record attacks and triggers) would be useful to avoid recall bias. Additionally, the relatively small sample size limits the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, the absence of C1 INH function measurements and genetic mutation analysis are significant limitations of our study. However, we believe that our study draws significant attention to the issues of pharmacophobia and stress as major triggers. In addition, our study supports the decreasing delay in HAE diagnosis in recent years.

Most of our patients were aware of attack triggers, yet high attack frequency persisted due to not using LTP agents and the stress experienced in their personal lives. Despite experiencing severe attacks necessitating intensive care and having a family history of HAE-related deaths, there was a pervasive pharmacophobia towards LTP treatment. Our study emphasizes the importance of comprehensive management strategies, including patient education and support programs, to address pharmacophobia and enhance patient outcomes. There is a need for more comprehensive studies on this subject in the future and future research is important to confirm these findings.