Introduction

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by persistent, sterile pustules on palms and soles. Recent genetic research indicates that PPP may not even be related to psoriasis [1]. PPP remains poorly understood, with its exact mechanisms yet unexplored and no standard treatment guidelines available to address its symptoms. Traditional therapies tend to have limited benefits while potentially having adverse side effects. Biologics, however, have already shown superior efficacy for psoriasis. In this paper we aim to review the efficacy and mechanisms of biologics for PPP treatment.

Anti-IL-1

Anakinra

The Interleukin-1 family comprises eleven members, divided into 7 agonists (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-33 and IL-36α/β/γ) and 4 antagonists (IL-1Ra/IL-36Ra, IL-37/38) [2].

Anakinra acts as an antagonist to IL-1 receptor (IL-1Ra), blocking both pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-1β from functioning properly. Both these cytokines have pro-inflammatory effects; IL-1α can stimulate T-cell-driven inflammation in skin tissues [3] while IL-1β induces keratinocytes to produce inflammatory chemokines [4]. Studies have noted increased levels of IL-1-related chemokines within PPP lesions [5]. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting IL-1 such as anakinra maybe helpful for PPP.

Previous phase II open-label dose-escalation trials demonstrating the efficacy of anakinra treatment on pustular psoriasis support this claim, with > 50% TBSAI reduction for half of 14 patients after 12 weeks of treatments [6]. Nonetheless, the randomised controlled trial (RCT) “APRICOT” demonstrated that anakinra showed limited effectiveness in treating PPP. In this trial, 31 PPP patients received anakinra for 8 weeks; however, there was no significant difference in the number of responders achieving palmoplantar pustulosis Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (ppPASI-50/75) compared to the placebo group [7]. The lack of significant results may be attributed to the brief duration of the follow-up period.

Moreover, there are few case reports indicating that anakinra is effective in treating diseases related to PPP such as SAPHO syndrome and generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) [8–10]. At present, the efficacy of anakinra in treating PPP is not fully understood, and need further studies.

Canakinumab

Unlike anakinra, canakinumab is an inhibitor that specifically targets IL-1β. There has been a case report of a PPP patient experiencing good results when using canakinumab in conjunction with cyclosporine, but the effectiveness of canakinumab alone in treatment was not satisfactory [11].

Anti-IL-8

HuMab 10F8

HuMab 10F8 is a novel fully human monoclonal antibody that effectively neutralizes IL-8. IL-8 is an inflammatory chemokine related to neutrophil activation, and previous studies have confirmed that levels of IL-8 are elevated in the lesions of PPP patients [12, 13]. Previous research also confirmed that levels of IL-8 in the epidermis and sweat glands of PPP patient lesions are increased [14], making IL-8 inhibitors a potential option for PPP treatment. A previous open-label, multicentre study showed that the number of pustules of PPP patients treated with HuMab 10F8 were significantly decreased, with most patients experiencing significant symptom relief [12]. However, due to the limited amount of research related to IL-8 biologics, the true efficacy of IL-8 inhibitors in improving PPP symptoms cannot be fully confirmed.

Anti-IL-17

Secukinumab

IL-17 is associated with psoriasis [15]. The IL-17 family cytokine comprises six subcomponents – A, B, C, D, E and F – with A and F being the main components. Both IL-17A/F are produced by Th17 cells and play an essential part in epithelial defence processes [16].

RCTs have proven the efficacy of secukinumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17A, for treating psoriasis [17–24]. Furthermore, recent investigations have uncovered significant elevation of IL-17A expression in lesions from PPP patients [25]. IL-17A is implicated in the abnormal proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes [26]. It also amplifies inflammation by boosting pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [27, 28].

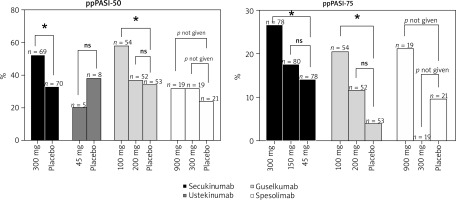

While the efficacy of secukinumab in treating psoriasis is well established, its effectiveness in treating PPP remains less thoroughly researched. Nevertheless, a phase 3b RCT focused on PPP patients demonstrated promising results for secukinumab. Notably, at week 16, 52.2% of patients receiving 300 mg of secukinumab achieved a ppPASI-50 score compared to 32.9% in the placebo group (p = 0.0159). Additionally, 26.6% of the same secukinumab group reached ppPASI-75, outperforming both the 150 mg secukinumab group (17.5%, p = 0.0411) and the placebo group (14.1%, p = 0.05722) (Figure 1). These results support the hypothesis that IL-17A is a key factor in the pathogenesis of PPP and suggest that secukinumab holds substantial therapeutic promise for this condition [29].

Furthermore, the efficacy of secukinumab in addressing conditions closely aligned with PPP, such as GPP and palmoplantar psoriasis, has been reported to be superior [30, 31]. This observation, drawn from current literature and empirical evidence, underscores Secukinumab’s established effectiveness in psoriasis treatment and suggests its potential applicability in managing PPP.

Ixekizumab

Ixekizumab, like secukinumab, is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17A. A phase 3 RCT with 351 psoriasis patients found that ixekizumab administration every 2 weeks resulted in 50% of patients achieving ppPASI-75 at week 4. Effectiveness of treatment progressively increased, with 90% of patients reaching ppPASI-75 by week 12 [32]. This emphasizes ixekizumab’s significant therapeutic efficacy for treating psoriasis while suggesting its potential use against similar skin conditions.

Brodalumab

Brodalumab, a human IgG2 monoclonal antibody, has shown significant effectiveness for managing both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in multiple RCTs [33–39]. Brodalumab stands apart from secukinumab and ixekizumab as it targets multiple subtypes of IL-17 including IL-17A, IL-17A/F, and IL-17F [40]. IL-17A/F could act on keratinocytes to produce neutrophil-attracting chemokines [41]. PPP lesions exhibit higher expression levels for IL-17A/C/D/F than normal palmar skin, and elevated serum IL-17 levels in PPP patients have also been observed [13]. Despite the theoretical advantage, a case series involving four PPP patients revealed minimal or no improvement after brodalumab treatment [42].

Anti-IL-12/23

Ustekinumab

IL-12 and IL-23, both secreted by myeloid cells, are crucial for the development of Th1 cells and the activity of Th17 cells, respectively [43]. Research has demonstrated that mRNA levels of IL-12/23p40 in psoriasis lesions exceed those in healthy skin [44], with associated cytokines also elevated due to IL-12 and IL-23 stimulation [45]. Ustekinumab, which specifically targets the p40 subunit shared by both IL-12 and IL-23, effectively reduces IL-17A and IL-17F production from Th17 cells [46]. Previous RCTs have shown that ustekinumab not only improves the symptoms and overall quality of life for psoriasis patients but also ameliorates symptoms of depression and anxiety [47]. However, a smaller RCT involving 13 PPP patients showed that 45 mg of ustekinumab failed to offer significant benefits over placebo at 16 weeks, with response rates of 10% and 20% for ppPASI-50, respectively (p = 1.000) (Figure 1). This suggests that IL-17 may play a more crucial role in PPP pathogenesis than IL-12/23, as evidenced by a 190-fold increase in IL-17 gene expression in PPP patients versus healthy individuals, with no significant changes in IL-12/23 subunits p19 and p40 expression levels [25]. Despite these findings, various case reports have documented mixed results [48–50].

In another study focused on the effectiveness of biologics for PPP, participants were treated with specific biologics for over 12 weeks. Results indicated that among 30 patients in the ustekinumab group, 37.9% achieved complete clearance, with a clinical symptom improvement rate of 70%, and the lowest rate of adverse reactions among the biologics evaluated [51]. These findings are in stark contrast to earlier results [25]. Furthermore, research indicates that 90 mg of ustekinumab significantly alleviates symptoms in patients with palmoplantar psoriasis. Of the 9 patients administered 90 mg, 67% achieved complete lesion clearance, compared to only 9% of the 11 patients treated with 45 mg [52].

Guselkumab

Compared to ustekinumab, the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab exhibits more significant therapeutic effects in treating PPP. Previous RCT reports demonstrate that PPP patients treated with guselkumab experienced significant improvements as early as week 2, with further improvements at weeks 16 and 52 [53, 54] (Figure 1). At week 16, the 100 mg group, the 200 mg group, and the placebo group had ppPASI-50 responders at 57.4%, 36.5%, and 34.0%, respectively; ppPASI-75 responders at 20.4%, 11.5%, and 3.8%, respectively. Guselkumab, identified as a fully human IgG1λ monoclonal antibody, acts by inhibiting the production of related cytokines through blocking the binding of IL-23 to its p19 subunit [55], suggesting that guselkumab represents a safe and effective option for PPP treatment.

Risankizumab

Risankizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. Numerous RCTs have documented its effectiveness in managing psoriasis [56–63]. Furthermore, risankizumab has demonstrated remarkable results in treating palmoplantar psoriasis, with the ppPASI90 response rate improving from 18.7% at week 4 to 81.2% by week 52 [64]. These findings suggest that risankizumab may be an option for diseases related to PPP, such as psoriasis and palmoplantar psoriasis. However, high quality evidence confirming its efficacy for PPP remains lacking.

TNF-α inhibitors

Infliximab

TNF-α serves as a pro-inflammatory mediator, facilitating T cell infiltration and modulating the antigen-presenting function of dendritic cells [67]. Inhibitors of TNF-α operate by modulating the IL-23/Th-17 pathway; specifically, they reduce IL-23 concentrations and decrease the levels of Th17 effector molecules such as IL-17 and IL-22, thereby exerting their therapeutic effects [68].

Infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody, exhibits a specific binding affinity to TNF-α [69]. Extensive research from numerous RCTs highlights infliximab’s robust effectiveness in managing both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [70–75]. Additionally, further RCTs confirm its success in treating palmoplantar psoriasis [76]. A multicentre retrospective study, which included 347 patients with PPP, revealed that infliximab provided the longest maintenance of efficacy, averaging 26 months. This was compared to ustekinumab at 21 months, adalimumab at 18 months, and etanercept at 8 months. Moreover, infliximab achieved the highest treatment success rate, with 40.6% of patients experiencing more than 75% improvement in symptoms. This is significantly better than the outcomes with ustekinumab (31%), adalimumab (33.3%), and etanercept (19.4%) [77].

Concurring with this perspective, a German study involving 92 patients compared infliximab with ustekinumab, adalimumab, and etanercept, revealed that up to 77.3% of PPP patients achieved symptom improvement, exceeding the improvement rates of other biologics. However, infliximab did not demonstrate superiority in the complete clearance rate (CC) compared to other biologics [51]. These results indicate that infliximab may be a viable option for PPP treatment. However, numerous reports highlight adverse reactions associated with infliximab [78–80].

Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that blocks the interaction between TNF-α and its receptors, the p55 and p75 subunits [81]. Similarly, numerous RCTs have confirmed adalimumab’s significant efficacy in treating psoriasis [82–87]. A multicentre, retrospective study demonstrated that 50% of 50 PPP patients treated with adalimumab experienced improvements in disease severity, and 17.6% achieved complete lesion clearance (CC) [51]. Case reports also suggest adalimumab’s effectiveness in treating PPP [88, 89], although it can sometimes induce PPP [90, 91].

Etanercept

Etanercept is a recombinant human TNF receptor p75 Fc fusion protein [92]. Previous studies have demonstrated significant effectiveness of etanercept in treating plaque psoriasis [93]. In PPP patients, several case reports document rapid symptom improvement following etanercept use [94, 95]. However, in a prior RCT involving PPP patients, 15 patients treated with etanercept for 12 weeks exhibited no superior outcomes compared to placebo [96]. Given the conflicting reports on etanercept’s efficacy in treating PPP, there is a need for further high-level clinical evidence to corroborate its effectiveness.

It is crucial to acknowledge that TNF-α inhibitor treatment does not universally benefit all forms of pustular psoriasis, and may, in some instances, exacerbate the condition [97, 98]. The underlying mechanisms of this paradoxical exacerbation remain incompletely understood. Some researchers postulate that this phenomenon could be linked to the activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Under anti-TNF-α therapy, these cells may commence overproduction of IFN-γ, subsequently activating T cells and prompting an increased production of TNF-α [99].

Anti-IL-36

Spesolimab

The IL-36 family comprises three agonists (IL-36α/β/γ) and one antagonist (IL-36Ra) [100]. Studies have demonstrated that Th17 cytokines can influence IL-36 levels, and conversely, IL-36 can affect the expression of Th17 cytokines [101]. A robust link between Th17 cytokines and psoriasis has been well established [102, 103]. The involvement of IL-36α/β/γ in psoriatic development is posited to occur through the IL23/IL-17A pathway [104].

Spesolimab, a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody, has been shown to be effective in blocking IL-36R signalling [105]. Elevated IL-36 levels have been observed in the lesions of patients with PPP compared to normal levels [106]. RCTs have demonstrated that spesolimab significantly improves symptoms in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) [107, 108]. Given the substantial overlap between GPP and PPP, spesolimab is considered a potential treatment for PPP. However, in a phase 2a, multicentre, double-blind, randomised pilot study including 59 patients, neither 900 mg nor 300 mg doses of spesolimab demonstrated significant efficacy over placebo in treating PPP. At 16 weeks, 31.6% of participants in both the 900 mg and 300 mg spesolimab groups, and 23.8% in the placebo group, achieved ppPASI-50; corresponding figures for ppPASI-75 were 21.1%, 0%, and 9.5% [109]. Another multicentre, double-blind, phase 2b RCT corroborated these findings as it also failed to meet efficacy endpoints with no significant differences in ppPASI scores observed between the spesolimab and placebo groups at 16 weeks [110]. Given these outcomes, spesolimab may not be an effective treatment option for PPP, although further phase 3 trials are required to confirm this assessment.

Conclusions

Currently, the effectiveness of biologic therapies in treating palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) appears to be inferior to their performance against plaque psoriasis. Among biologics proven effective in randomised controlled trials, the IL-17 inhibitor, secukinumab, and the IL-23 inhibitor, guselkumab, have exhibited relatively higher effectiveness compared to others. Nonetheless, the efficacy of several other biologics, including IL-17 inhibitors like ixekizumab and brodalumab, and IL-23 inhibitors such as risankizumab, as well as various TNF inhibitors, remains uncertain due to the lack of robust clinical efficacy data. Extensive clinical research is essential to identify more effective biologic treatments for PPP. The response of PPP to biologics varies significantly, necessitating additional investigation and clinical trials to pinpoint the most beneficial treatments. While biologics hold considerable promise for alleviating symptoms in PPP patients, selecting the most suitable biologic for an individual patient at the optimal time remains a significant challenge (Supplementary).