Introduction

The spleen, the largest peripheral lymphoid organ in the human body, assumes a pivotal role in orchestrating immune responses, modulating endocrine functions, and regulating blood cell dynamics [1]. The generation of memory T and B cells in the spleen constitutes a significant influence on subsequent immune reactions [2–4]. In recent years, splenectomy has emerged as a therapeutic strategy for conditions such as splenomegaly, hypersplenism, space-occupying lesions, injuries, and deformities. Initially, total splenectomy was the preferred choice, but the emergence of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) prompted a critical re-evaluation. Studies have shown an elevated risk of infection, malignancy, and deep vein thrombosis after total splenectomy [5, 6].

Currently, the practice of partial splenectomy is gaining prominence in clinical settings, and the utilisation of laparoscopic technology in this procedure is on the rise [7–9]. However, despite studies confirming the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic partial splenectomy (LPS), emphasising manageable technical aspects, there remains a notable scarcity of comparative studies with open partial splenectomy (OPS) [10]. In 2019, Costi et al. conducted a comprehensive systematic review of partial splenectomy procedures from 1960 to December 2017 [11]. The review indicated that nearly half of splenectomy procedures addressed haematological disorders, with only 18.6% for benign splenic tumours, and a mere 8.6% for traumatic splenic rupture. There is a lack of reports on the application of LPS in cases involving benign splenic tumours and traumatic splenic rupture [12].

Consequently, this study embarks on a comparative analysis of patients undergoing LPS or OPS due to traumatic splenic rupture or splenic tumours during the same timeframe. The aim is to investigate the feasibility, safety, and early postoperative recovery of patients subjected to LPS and OPS, elucidating the respective advantages and disadvantages of these surgical approaches.

Aim

To investigate and compare the feasibility, safety, and early postoperative recovery associated with LPS and OPS in patients with benign splenic tumours and traumatic splenic rupture.

Material and methods

Patients

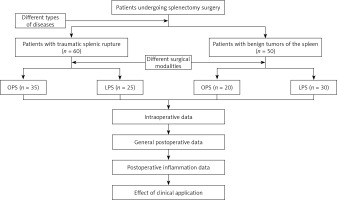

Clinical records of patients undergoing partial splenectomy due to splenic rupture at the Department of General Surgery, Dongshan County Hospital, from March 2019 to May 2022, were retrospectively gathered. Of the 60 patients with traumatic splenic rupture, 35 had OPS and 25 had LPS. Additionally, of 50 patients diagnosed with benign splenic tumours, 20 had OPS and 30 had LPS. Cases involving concomitant splenectomy with other surgeries were excluded. A flowchart is shown in Figure 1. All procedures were performed by the surgical team in the Department of General Surgery at our institution. Data for this study were collected jointly by members of the research team, and any disagreements during data evaluation were discussed and voted on. Ethical approval was obtained from the hospital’s Ethics Committee, and participants provided informed consent.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients with traumatic splenic rupture, aged 25 to 60 years, with an injury time of less than 48 h, confirmed through CT or diagnostic abdominal puncture. Vital signs were stable or stabilised after symptomatic treatment. Spleen injury was the main cause, without hemopneumothorax, multiple rib fractures, liver, intestinal, spinal, pelvic fractures, or systemic complications. (2) Cases with mild splenic enlargement or below, and no other organ complications.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Pregnant or lactating women; (2) patients with cirrhosis, portal hypertension, or hypersplenism; (3) patients with haematological disorders; (4) patients with malignant splenic tumours; (5) cases necessitating additional surgeries.

Indications for the difference between OPS and LPS [13, 14] were as follows: focused on patients with coagulopathy, heart failure, inability to tolerate general anaesthesia, history of multiple abdominal surgeries, or severe intra-abdominal infection after surgery. If any of these indications are met, OPS is chosen; otherwise, LPS is selected.

Surgical methods

OPS procedure

Patients received general anaesthesia and were positioned supine based on clinical requirements. A left subcostal or left upper rectus abdominis incision was made. Caution was exercised to protect the healthy side of the splenic ligament, avoiding excessive detachment to mitigate complications. Splenic blood vessel dissection emphasised pancreas protection. Transverse splenectomy was performed using a Johnson & Johnson USA ULTRACISION HARMONIC SCALPEL GEN300 SYSTEM. A negative pressure drainage tube was placed near the spleen. Pictures of the operation are shown in Photos 1 A–D.

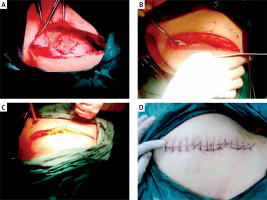

Photo 1

Entry incision of open splenectomy. A – Diagonal incision in the left upper quadrant below the costal margin; B – haemostasis in the surgical area after spleen resection; C – begining to suture the incision; D – the incision is sutured

For secondary blood vessel exposure, a gentle approach was adopted to prevent unintended injury. Following ligation of vessels supplying the lesion, transverse splenectomy was performed within the ischaemic area using an ultrasonic knife, maintaining a 1 cm distance from the ischaemic boundary. In splenic rupture cases, an autologous blood transfusion device was available.

LPS procedure

Patients received general anaesthesia via tracheal intubation and were positioned in a right lateral decubitus posture. A 5-hole layout was employed based on spleen size and position.

Caution prevented excessive dissociation of the healthy side of the splenic ligament. Depending on the case, the splenic artery trunk was dissected at the upper edge of the pancreatic tail. Meticulous splenic blood vessel dissection prioritised pancreas preservation. Delicate handling and Hem-o-lock clamps were used for vessel ligation. Pictures of the operation are shown in Photos 2 A–F.

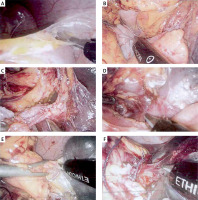

Photo 2

Part of the picture of laparoscopic splenectomy. A – Dissection of splenic flexure; B – dissection of short gastric vessels; C – exploration of Splenic vessels; D – dissection and release of splenic ligament; E – ligation and dissection of short gastric vessels; F – dissection and release of splenic ligament

Following this, transverse splenectomy was performed within the ischaemic area using an ultrasonic knife, maintaining a 1 cm distance from the ischaemic boundary. The assistant maintained a clear field using electrocoagulation instruments and suction devices. The excised lesion site was securely placed in a specimen bag and removed through an enlarged umbilical incision. A negative pressure drainage tube was inserted proximate to the spleen. A backup autologous blood transfusion device was available for splenic rupture cases. No significant differences in surgical instruments were observed between OPS and LPS procedures during the study period.

Data collection

Preoperative data

Pertinent preoperative information included patient age, gender, lesion location, tumour size, spleen size, underlying medical conditions, and any prior history of abdominal surgery for patients diagnosed with benign splenic tumours. For patients with traumatic splenic rupture, preoperative data encompassed age, gender, lesion location, splenic size, underlying medical conditions, history of prior abdominal surgeries, cause of injury, time of admission, preoperative heart rate, preoperative haemoglobin levels, and grading of splenic injury (utilising the Tianjin 4-level method in China) [15].

Intraoperative data

Intraoperative records consisted of surgical duration, volume of intraoperative bleeding, quantity and volume of allogeneic transfusions, size of splenectomy, and the conversion rate to laparotomy for patients with benign splenic tumours in the LPS group. Additionally, for patients with traumatic splenic rupture, intraoperative data included surgical duration, total intraoperative blood loss, allogeneic blood transfusions during surgery, the number of cases requiring intraoperative allogeneic blood transfusion, size of splenectomy, conversion rate to laparotomy within the LPS group, volume of autologous blood transfusions, and postoperative bleeding volume.

Postoperative data

The postoperative data collection encompassed parameters such as postoperative analgesia frequency, duration of postoperative bowel movement recovery, length of postoperative hospital stay, duration of postoperative drainage, drainage volume on the third day post-surgery, occurrence of postoperative complications, proportion of remaining spleen, and postoperative inflammatory markers (including white blood cell count, white blood cell count to lymphocyte count ratio [WLR], and neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio [NLR] on days 1, 3, and 5 after surgery), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), C-reactive protein (CRP), calcitonin (PCT), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (MLR), for both patient groups.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 23.0 software. Data with a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and intergroup mean comparisons were performed using a t-test. If the data did not meet the normal distribution, the data were expressed as median (interquartile spacing), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison between groups. Repeated measurement analysis of variance was utilised to analyse repeated measurement data. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies or percentages, and intergroup comparisons were conducted using χ2 tests when conditions were met; Fisher’s exact test was employed when the conditions were not met. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Traumatic splenic rupture group

Preoperative data

This study involved 60 patients with traumatic splenic rupture, including 35 undergoing OPS and 25 undergoing LPS. Comparative analysis showed no statistically significant differences in age, gender, lesion location, spleen size, medical conditions, history of abdominal surgeries, cause of injury, admission time, preoperative heart rate, preoperative haemoglobin levels, and grading of spleen injury between the 2 groups (p > 0.05) (Table I).

Table I

Preoperative data of traumatic splenic rupture group

Intraoperative data

A significant difference in surgical duration was observed between the OPS and LPS groups (87.63 ±26.25 vs. 127.43 ±33.13 min, t = 4.831, p < 0.001), with OPS having shorter times. No significant differences (p > 0.05) were noted in total intraoperative bleeding, allogeneic blood transfusions, cases requiring transfusion, splenectomy extent, autologous transfusions, and postoperative bleeding. No conversions to open surgery occurred in the LSP group (Table II).

Table II

Intraoperative and postoperative information of the traumatic splenic rupture group

Postoperative data

Comparative analysis revealed significant differences in postoperative analgesia frequency (2.34 ±0.41 vs. 1.65 ±0.48 times, t = 3.469, p < 0.001) and bowel movement recovery time (3.67 ±0.87 vs. 2.45 ±0.66 days, t = 4.312, p < 0.001), favouring LPS. However, no significant differences were observed in other postoperative parameters (p > 0.05) (Table II).

Repeated measurement analysis of variance was used to assess postoperative inflammatory indicators in both patient groups, as depicted in Table III. The summary of the results is as follows: There was a significant interaction observed between white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR in both groups (F white blood cell count = 341.141, p < 0.001; FWLR = 231.154, p < 0.001; FNLR = 174.141, p < 0.001; FMLR = 124.123, p < 0.001; FCRP = 64.381, p < 0.001; FPCT = 62.195, p < 0.001; FIL-6 = 45.592, p < 0.001), indicating distinct variations in white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR at the 3 designated time points. Additionally, all indicators in both patient groups displayed a decline over time (F white blood cell count = 125.631, p < 0.001; FWLR = 143.432, p < 0.001; FNLR = 219.543, p < 0.001; FMLR = 141.132, p < 0.001; FCRP = 72.481, p < 0.001; FPCT = 61.244, p < 0.001; FIL-6 = 56.491, p < 0.001), signifying noteworthy alterations in white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR over the duration of the study.

Table III

Postoperative inflammatory data of the traumatic splenic rupture group

| Factors | Days | OPS group (n = 35) | LPS group (n = 25) | F interactive/P interactivevalue | F time/P time value | F treatment/P-Treatment value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count [× 109/l] | 1da | 15.53 ±4.31 | 11.31 ±3.41 | 341.141/< 0.001 | 125.631/< 0.001 | 141.154/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 13.42 ±3.24 | 10.32 ±2.31 | ||||

| 5db | 8.32 ±2.26 | 7.81 ±2.13 | ||||

| WLR | 1da | 17.45 ±8.81 | 7.43 ±2.13 | 231.154/< 0.001 | 143.432/< 0.001 | 252.132/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 11.89 ±4.52 | 6.43 ±1.67 | ||||

| 5db | 6.43 ±1.32 | 4.89 ±1.23 | ||||

| NLR | 1da | 16.34 ±6.74 | 6.12 ±2.13 | 174.141/< 0.001 | 219.543/< 0.001 | 190.421/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 11.29 ±4.31 | 4.89 ±1.31 | ||||

| 5db | 4.51 ±1.45 | 3.41 ±1.11 | ||||

| PLR | 1db | 152.47 ±45.18 | 185.99 ±67.90 | 1.424/0.993 | 2.434/0.944 | 1.454/0.993 |

| 3db | 164.34 ±67.41 | 180.38 ±79.34 | ||||

| 5db | 176.78 ±89.91 | 195.78 ±89.31 | ||||

| MLR | 1da | 1.24 ±0.67 | 0.67 ±0.11 | 124.123/< 0.001 | 141.132/< 0.001 | 122.151/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 1.13 ±0.36 | 0.51 ±0.12 | ||||

| 5db | 0.53 ±0.16 | 0.43 ±0.15 | ||||

| CRP | 1da | 48.28 ±13.48 | 39.46 ±12.49 | 64.381/0.001 | 72.481/0.001 | 92.453/0.001 |

| 3da | 21.59 ±6.32 | 13.31 ±6.40 | ||||

| 5db | 9.48 ±4.20 | 6.48 ±3.39 | ||||

| PCT | 1da | 3.01 ±0.54 | 2.56 ±0.32 | 62.195/0.001 | 61.244/0.001 | 90.678/0.001 |

| 3da | 1.67 ±0.43 | 1.11 ±0.34 | ||||

| 5db | 0.82 ±0.13 | 0.65 ±0.22 | ||||

| IL-6 | 1da | 31.48 ±9.40 | 26.48 ±7.28 | 45.592/0.001 | 56.491/0.001 | 89.491/0.001 |

| 3da | 15.18 ±5.11 | 11.38 ±6.32 | ||||

| 5db | 4.37 ±2.43 | 3.93 ±1.49 |

Ultimately, the different surgical approaches had diverse effects on the white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR of the 2 patient groups (F white blood cell count = 141.154, p < 0.001; FWLR = 252.132, p < 0.001; FNLR = 190.421, p < 0.001; FMLR = 122.151, p < 0.001; FCRP = 92.453, p < 0.001; FPCT = 90.678, p < 0.001; FIL-6 = 89.491, p < 0.001). Further comparison of the daily indicators between the 2 groups revealed statistically significant disparities in white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR on the first and third postoperative days (p < 0.05), with the OPS group displaying higher values than the LPS group. However, there was no statistically significant difference in white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR between the 2 patient groups on the fifth day post-surgery (p > 0.05). Moreover, no notable difference in PLR was observed between the 2 groups at various time points (p > 0.05), as outlined in Table III.

Benign splenic tumour group

Preoperative data

This study involved 50 patients with benign splenic tumours, including 20 undergoing OPS and 30 undergoing LPS. No significant differences were identified in age, gender, lesion location, tumour size, spleen size, medical conditions, and prior surgeries between the 2 groups (p > 0.05) (Table IV).

Table IV

Preoperative data of the benign splenic tumour group

Intraoperative data

No significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between OPS and LPS groups in surgical duration, overall intraoperative bleeding, transfusions, cases requiring transfusion, and splenectomy size. No conversions to open surgery occurred in the LSP group (Table V).

Table V

Intraoperative and postoperative information of the benign splenic tumours group

Postoperative data

Significant differences were observed in postoperative analgesia frequency (1.83 ±0.42 vs. 1.15 ±0.65 times, t = 3.654, p < 0.001) and exhaust time (3.21 ±0.79 vs. 2.12 ±0.78 days, t = 3.422, p < 0.001), favouring LPS. Additionally, the LPS group showed superior outcomes in hospital stay, drainage time, third-day drainage volume, total hospitalisation cost, and postoperative complications. No significant difference was observed in the proportion of remaining spleen (p > 0.05) (Table V).

Repeated measurement analysis of variance was used to scrutinise postoperative inflammatory indicators in the 2 patient groups. Summarily, the outcomes are as follows: the interaction among the white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR in the 2 groups was noteworthy (F white blood cell count = 211.541, p < 0.001; FWLR = 214.211, p < 0.001; FNLR = 135.452, p < 0.001; FMLR = 221.342, p < 0.001; FCRP = 78.159, p < 0.001; FPCT = 123.581, p < 0.001; FIL-6 = 78.592, p < 0.001). This signified that the white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR exhibited varying individual effects at the 4 time points for MLR. Moreover, all indicators in both patient groups experienced a decline over time (F white blood cell count = 146.542, p < 0.001; FWLR = 123.441, p < 0.001; FNLR = 321.323, p < 0.001; FMLR = 143.563, p < 0.001; FCRP = 103.381, p < 0.001; FPCT = 61.244, p < 0.001; FIL-6 = 99.401, p 0.001), denoting significant alterations in white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR over time. Finally, the distinct surgical approaches had divergent impacts on the white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR of the 2 patient groups (F white blood cell count = 134.112, p < 0.001; FWLR = 231.341, p < 0.001; FNLR = 123.212, p < 0.001; FMLR = 175.841, p < 0.001; FCRP = 110.392, p < 0.001; FPCT = 90.678, p < 0.001; FIL-6 = 121.492, p < 0.001). Upon further comparison of the daily indicators between the 2 groups of patients, the results demonstrated statistically significant disparities in white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR on the first and third days (p < 0.05), with the OPS group exhibiting higher values than the LPS group. Conversely, there were no statistically significant differences in white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, CRP, PCT, IL-6, and MLR between the 2 patient groups on day 5 (p > 0.05). Additionally, there was no statistically significant distinction in PLR between the 2 patient groups at different time points (p > 0.05), as detailed in Table VI.

Table VI

Postoperative inflammatory data of the benign splenic tumour group

| Factors | Days | OPS group (n = 20) | LPS group (n = 30) | F interactive/P interactivevalue | F time/P time value | F treatment/PTreatmentvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count [×109/l] | 1da | 16.98 ±1.41 | 13.22 ±2.13 | 211.541/< 0.001 | 146.542/< 0.001 | 134.112/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 12.34 ±2.78 | 10.21 ±3.21 | ||||

| 5db | 8.45 ±1.12 | 8.21 ±1.98 | ||||

| WLR | 1da | 22.34 ±4.31 | 12.57 ±4.89 | 214.211/< 0.001 | 123.441/< 0.001 | 231.341/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 16.45 ±5.32 | 11.34 ±3.21 | ||||

| 5db | 7.23 ±1.21 | 6.45 ±1.03 | ||||

| NLR | 1da | 16.42 ±5.34 | 11.33 ±3.47 | 135.452/< 0.001 | 321.323/< 0.001 | 123.212/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 13.31 ±4.31 | 9.34 ±4.64 | ||||

| 5db | 4.31 ±2.14 | 4.56 ±1.87 | ||||

| PLR | 1db | 210.45 ±56.24 | 202.41 ±56.21 | 1.634/0.992 | 2.132/0.947 | 2.534/0.944 |

| 3db | 189.41 ±45.56 | 178.481 ±67.53 | ||||

| 5db | 201.45 ±89.45 | 220.431 ±79.63 | ||||

| MLR | 1da | 1.45 ±0.34 | 0.93 ±0.28 | 221.342/< 0.001 | 143.563/< 0.001 | 175.841/< 0.001 |

| 3da | 1.32 ±0.32 | 0.78 ±0.12 | ||||

| 5db | 0.69 ±0.42 | 0.56 ±0.32 | ||||

| CRP | 1da | 47.59 ±11.48 | 36.49 ±10.34 | 78.159/0.001 | 103.381/0.001 | 110.392/0.001 |

| 3da | 23.42 ±7.59 | 14.69 ±6.62 | ||||

| 5db | 9.62 ±4.20 | 6.64 ±3.36 | ||||

| PCT | 1da | 3.11 ±0.47 | 2.47 ±0.41 | 123.581/0.001 | 61.244/0.001 | 90.678/0.001 |

| 3da | 1.58 ±0.43 | 1.21 ±0.44 | ||||

| 5db | 0.79 ±0.13 | 0.61 ±0.22 | ||||

| IL-6 | 1da | 32.48 ±10.30 | 26.79 ±8.58 | 78.592/0.001 | 99.401/0.001 | 121.492/0.001 |

| 3da | 16.33 ±6.40 | 11.04 ±6.43 | ||||

| 5db | 4.11 ±2.43 | 3.73 ±1.32 |

Discussion

Our study compared LPS with OPS in patients with benign splenic tumours and traumatic splenic rupture. The results demonstrate several significant advantages associated with LPS over OPS. Specifically, LPS was found to be associated with minimal surgical trauma, reduced early postoperative inflammatory response, milder wound pain, and faster recovery of gastrointestinal function compared to OPS. These findings highlight the potential clinical benefits of LPS in the management of splenic disorders, emphasising its feasibility and safety in selected patient populations.

In the comparative analysis of intraoperative data, we noted that patients in the LPS group with traumatic splenic rupture experienced prolonged surgical time compared to the OPS group. Although no cases required conversion to open surgery in the LPS group for patients with benign splenic tumours and traumatic splenic rupture in our study, previous research has reported a certain probability of conversion to OPS [8]. Regarding the comparative analysis of postoperative general data, the LPS group demonstrated a lower frequency of postoperative analgesia and a shorter postoperative exhaust time compared to the OPS group for both diseases. This finding is consistent with conclusions drawn from prior comparative studies on laparoscopic and open surgery, where laparoscopic surgery patients experienced milder postoperative pain and a swifter recovery of gastrointestinal function [16, 17]. Importantly, LPS involves a significantly smaller surgical incision than OPS, resulting in reduced postoperative pain for patients and enabling earlier mobilisation.

Unlike previous studies in different medical fields where laparoscopic surgery often resulted in shorter postoperative hospital stays [16–18], our study found no statistically significant difference in postoperative hospital stay between the 2 groups of patients with benign tumours and splenic rupture. This aligns with prior research on LPS, which also reported prolonged hospital stays for patients [8, 19]. The primary reason lies in the longer healing duration and increased leakage associated with the splenic section after partial splenectomy, necessitating prolonged drainage tube retention. Consequently, the extension of extubation time translates into an elongation of postoperative hospitalisation. It is worth noting that the advantage of minimally invasive LPS may not manifest in shorter hospital stays.

Higher values of NLR, PLR, WLR, and MLR correspond to a heightened level of inflammation within the body [20–24]. Studies by Bergström et al. [25] and Aminsharifi et al. [26] demonstrated that minimally invasive surgery induces a lesser inflammatory response due to reduced surgical trauma compared to open surgery. The study by Sim et al. [23] affirmed that the postoperative increase in the inflammatory biomarker NLR during laparoscopic hysterectomy was lower than that observed in the open hysterectomy group. The study by Hosseini et al. [27] showed that NLR and PLR markers suggest that laparoscopic surgery may be a preferable choice for colorectal surgery over open surgery due to a lower induction of inflammation. A study by Zheng et al. [24] demonstrated that minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy (MIDP) significantly reduces NLR compared to open distal pancreatectomy.

In this study, the white blood cell count, WLR, NLR, and MLR of patients in the OPS group were higher than those in the LPS group on the first and third days, with no statistically significant difference on the fifth day. This finding aligns with previous research, as OPS entails a larger incision and considerable damage to the abdominal wall structure. Intraoperative movement of the spleen during OPS may exacerbate spleen damage and significantly disturb other organs within the abdominal cavity. Conversely, LPS involves a smaller abdominal wall incision, and laparoscopy allows for an expanded surgical field of view, facilitating precise operations [28]. The reduced surgical trauma associated with LPS results in a lower induction of inflammation. However, there was no statistically significant difference in PLR between the LPS and OPS groups on the first, third, and fifth days after surgery for both diseases. One possible explanation is that partial splenectomy may lead to a more significant increase in platelet count compared to other non-splenic surgeries. This increase in platelet count is not primarily linked to postoperative inflammation but is mainly attributed to a decrease in platelet exchange pools within the spleen [29].

Of course, there are also certain shortcomings in this study. Firstly, as a retrospective study, this study did not use methods such as randomisation and blinding; Secondly, due to the high surgical difficulty and narrow indication range of partial splenectomy for benign splenic tumours and splenic rupture, the number of cases is relatively small; Due to data limitations in the retrospective study, other immune indicators and first time out of bed activity time were not analysed. Further exploration is needed in the future, striving to achieve large sample and multi-centre research.

Conclusions

LPS demonstrates significant advantages over OPS in terms of minimal surgical trauma, reduced early postoperative inflammatory response, milder wound pain, and faster recovery of gastrointestinal function. These findings underscore the potential benefits of LPS in patients with benign splenic tumours and traumatic splenic rupture. Future research could explore additional clinical outcomes and long-term follow-up data to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of LPS compared to OPS.