Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD), also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, has an unknown aetiology and is generally believed to be caused by acute systemic nonspecific small- and medium-vessel vasculitis triggered by infectious factors [1]. According to statistics, the current global incidence of KD is approximately 49.4 per 100,000 people, with more than 50% of the cases being children under 2 years of age [2]. During the acute phase of KD, the increase of inflammatory factors leads to vascular endothelial cell proliferation and migration that induces progression into systemic vascular inflammatory damage, and vascular endothelial cell damage also causes frequent episodes of coronary artery lesions (CAL) in children [3]. Meanwhile, KD, as a vascular injury inflammation with a highly activated immune system, can cause irreversible changes in the vascular diameter after CAL, potentially increasing the risk of coronary complications even after treatment [4]. In recent years, with the increasingly advanced medical technology, the survival rate of all kinds of premature infants and newborns with congenital defects has become higher and higher, accompanied by an increasing incidence of KD [5]. Therefore, how to effectively evaluate the occurrence of CAL in KD is of great significance to protect the health of children.

Research has shown that KD is a clinical syndrome caused by acute abnormal activation of the autoimmune system induced by infectious factors on the basis of genetic predisposition, which is related to abnormal increases in chemokines and inflammatory factors triggered by immune disorders [6]. Therefore, research has been focused on changes in the inflammatory mediators in KD.

Cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinases (Caspase) are a group of proteases with a similar structure present in the cytoplasm, which have a close relationship with eukaryotic cell apoptosis, participate in cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis regulation, and are the key substance of inflammatory signal transduction [7]. Among them, caspase-1 is one of the most widely involved caspase family members in cardiovascular diseases, which has been confirmed to participate in multiple pathological processes such as angiogenesis, myocardial hypertrophy, unstable plaques of the artery wall, myocardial fibrosis, and other cardiovascular alterations [8, 9]. For CAL, caspase-1 also plays an important role [10–12]. More recently, a study by Jin et al. even found that the use of caspase-1 inhibitors is expected to be a new therapeutic option for atherosclerosis [13]. Qian et al. also showed that caspase-1 has the ability to regulate vascular inflammation in ischemic stroke [14]. All these studies suggest that we may have an important potential link between caspase-1 and KD.

Currently, the incidence of KD is increasing year by year, and its threat to children’s health has to be emphasized. As an excellent quantitative indicator, caspase-1 has great potential for clinical application in both KD and CAL in children with KD. However, in children with KD, the specific role of caspase-1 is not clear, and whether the relationship between caspase-1 and CAL will be affected by KD remains to be confirmed.

Aim

Accordingly, in this study, we will explore the clinical significance of caspase-1 in KD combined with CAL, and further explore its influence on vascular smooth muscle cells so as to provide new research ideas and basis for future diagnosis and treatment of KD.

Material and methods

Study subjects

A prospective analysis was conducted on 67 children with acute KD admitted to our hospital from August 2022 to April 2023 (research group) and 67 healthy outpatient children during the same period (control group). All the subjects provided written informed consent and follow the Declaration of Helsinki/the Declaration of Helsinki is followed in conducting the study, and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Criteria for patient enrolment and exclusion

Research group: all children aged 6 months to 6 years old who met the KD diagnostic guidelines [15], with confirmed diagnosis by our hospital and complete medical records. Routine examinations including liver and renal function, electrocardiogram, faecal/urine, blood, etc., were performed after admission to the hospital. Based on the results of the examinations, children with other underlying diseases such as rheumatic immune diseases and cardiovascular diseases that could cause coronary artery damage, serious infections, congenital heart disease and/or cardiomyopathy, severe arrhythmias, kidney disease, or mental illness were excluded. Control group: healthy outpatient children aged 6 months to 6 years without KD or previous medical history were included. The exclusion criteria were the same as those of the research group.

CAL diagnostic criteria

Ultrasound (GE Vivid E95 colour Doppler ultrasound, USA) performed on all children with KD. The diameters of the right coronary artery, left main coronary artery, left anterior descending branch, and circumflex coronary artery were measured, and the Z-value was calculated based on the coronary artery diameter measured by echocardiography and the child’s body surface area. Z-value < 2: CAL negative (-); a Z-value greater than or equal to 2.5 or within the range of 2.0~ < 2.5, accompanied by enhanced echogenicity around the coronary artery or coronary artery: CAL positive (+). In the research group, 30 children were CAL+ and 37 children were CAL-.

Sample collection and testing

First, we drew 2 ml of fasting peripheral blood from children in the research group at the time of admission, after treatment, and the control group at the time of admission for testing. These blood samples were centrifuged at room temperature for 10 min (3000×g), and the serum was collected and stored in a –80°C refrigerator. Caspase-1, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) strictly following the kit instructions, with the kits all ordered from Shanghai Xuanya Biotech (China). All children were treated with g globulin injections after admission to the hospital. Caspase-1 was measured at the time of admission (T0), after treatment with g globulin injections (T1), 10 days after discharge from the hospital (T2), 1 month after discharge from the hospital (T3), and 3 months after discharge from the hospital (T4) in the children in the research group.

Cell data

Human coronary artery smooth muscle cells (HCASMCs), purchased from BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing, China), were cultured in a supporting medium with 37°C, 5% CO2 + 95% air.

Cell transfection

Caspase-1 abnormal expression vectors, designed and constructed by Biorun Biotech Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, Hubei, China), were transfected into logarithmic-growth-phase HCASMCs according to Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the concentration of caspase-1 in the cell culture supernatant was detected to confirm the success rate of transfection. Among them, HCASMCs transfected with the caspase-1 empty vector, overexpression vector, and silencing vector were labelled as blank group, group A, and group B, respectively.

Cell viability assay

When the cell growth of each group reached 80%, the cells were washed with PBS 3 times, digested, and resuspended for inoculation into 96-well plates with 3–6 × 103 cells/well, with 4 duplicate wells set in each group. 10 μl of CCK-8 solution was added into one well at 24, 48, and 72 h (37°C, 5% CO2 + 95% air) of culture, respectively, and the optical density (OD) at 450 nm was detected 2 h after culture using a microplate reader (Varioskan LUX enzyme labeler, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Cell growth curves were drawn.

Apoptosis and cell cycle assays

Cells were washed with PBS and digested by adding ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free trypsin; 100 μl of cell suspension (5 × 105 cells/ml) was taken after resuspension in PBS and placed in a clean centrifuge tube, and 5 μl of Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodine (PI) reagent (Med Chem Express, USA) were added sequentially, mixed well, and then incubated for 15 min at room temperature with protection from light, the apoptosis rate was detected by flow cytometry and the cell cycle was analyzed.

Outcome measures

Differences in peripheral blood expression of caspase-1 and inflammatory factors between the research and control groups were compared, and the diagnostic value of caspase-1 for KD was analyzed. In addition, the difference in caspase-1 expression between CAL+ and CAL- children in the research group was further observed, and its diagnostic value for CAL was discussed. Furthermore, changes in HCASMC biological behaviours after interfering with caspase-1 expression were observed.

Statistical analysis

This study used SPSS 24.0 for statistical analysis, with p < 0.05 indicating the presence of statistical significance. Categorical variables, denoted by [n (%)], were comparatively analyzed between groups with the χ2 test. The means ± s was used to statistically describe continuous variables, whose between- and within-group comparisons employed independent sample t tests and paired t tests, respectively. The diagnostic value was assessed with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and the correlation was determined by Pearson correlation coefficients. Correlates were analyzed using logistic regression.

Results

Comparison of clinical data

Comparing children’s age, sex, weight, and other baseline data, we found no statistical inter-group significance (p > 0.05), suggesting that comparability (Table 1).

Table 1

Comparison of clinical baseline data

Clinical significance of caspase-1 in KD

Peripheral blood caspase-1 was 8.73 ±3.71 pg/ml in the acute phase of the research group, which was significantly higher (p < 0.001) compared to 12.25 ±3.98 pg/ml in the control group (p < 0.001). According to ROC analysis, when peripheral blood caspase-1 expression was greater than 12.62 pg/ml, the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing the occurrence of KD were 50.75% and 89.55%, respectively (p < 0.001). In addition, the changes in caspase-1 at each time point in the children in the research group were detected, and it was seen that the concentration of caspase-1 gradually decreased with the treatment and reached its lowest value (8.53 ±1.72 pg/ml) at T4 (p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Relationship between caspase-1 and inflammatory responses in KD

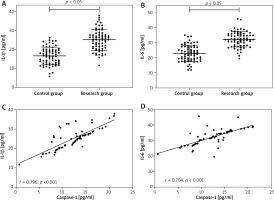

The results of inflammatory factors showed that IL-1β and IL-6 in the research group were 25.15 ±5.49 pg/ml and 32.09 ±5.07 pg/ml, respectively, which were higher than those in the control group (p < 0.001). Pearson correlation coefficient identified a positive association of caspase-1 with IL-1β (r = 0.796, p < 0.001) and IL-6 (r = 0.704, p < 0.001) in children in the research group during the acute phase (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Relationship between Caspase-1 and inflammatory responses in DK. A – IL-1β was higher in research group than in the control group. B – IL-6 was higher in research group than in the control group. C – Caspase-1 and IL-1β were positively correlated in research group. D – Caspase-1 and IL-6 were positively correlated in research group

Relationship between caspase-1 and CAL in KD children

In contrast, the caspase-1 level in the research group was 13.70 ±4.49 pg/ml in the acute phase in the CAL+ children, which was higher than in the CAL- children (p < 0.001). ROC curves showed that the sensitivity and specificity of CAL in the diagnosis of CAL in children with KD were 60.00% and 81.08% (p < 0.001), respectively, when caspase-1 was > 13.67 pg/ml in the acute phase (Figure 3).

Analysis of factors associated with the development of CAL in children with KD

Finally, we also carried out a preliminary analysis of the factors associated with the development of CAL in children with KD, and after comparing the age, weight, and sex data of the CAL+ children with those of the CAL- children, it was found that none of the differences were statistically significant (p > 0.05). Creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), albumin (ALB), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP) were further compared between the two groups, Platelet (PLT), etc., also did not show significant differences (p > 0.05, Table 2). Only caspase-1 was significantly different between CAL+ and CAL- children, so logistic regression analysis was performed with CAL as the independent variable (CAL- was assigned a value of 1 and CAL+ was assigned a value of 2) and caspase-1 as the covariate (analyzed using the raw data). The results showed that caspase-1 was an independent risk factor for the development of CAL in children with KD (p < 0.001, Table 3).

Table 2

Univariate analysis of factors affecting the occurrence of CAL in children with KD

Effect of caspase-1 on HCASMCs

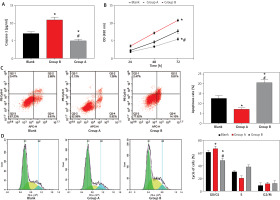

After transfection of caspase-1 aberrant expression vector, it was found that caspase-1 in group A was 11.03 ±0.70 pg/ml, which was higher than that in the blank group, while caspase-1 in group B was 5.07 ±0.35 pg/ml, which is lower than that in the blank group (p < 0.001), which confirmed that the transfection was successful. Subsequently, we found through the MTT assay that the cell proliferation was enhanced in group A compared with the blank group and group B, while group B had weaker cell proliferation than the blank group (p < 0.001). Flow cytometry showed that the apoptosis rate of group A was 7.30 ±0.46%, which was the lowest among the three groups, and the cells were significantly blocked in the G0/G1 phase (p < 0.001); whereas the apoptosis rate of group B was 20.78 ±1.27%, which was higher than that of the blank group, and the G0/G1 phase was shortened (p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Effect of Caspase-1 on HCASMCs. A – Detection of Caspase-1 expression to verify transfection success. B – Effect of Caspase-1 on the proliferative capacity of HCASMCs. C – Effect of Caspase-1 on the apoptosis rate of HCASMCs. D – Effect of Caspase-1 on the cycle of HCASMCs. *P < 0.05 compared to blank group and #p < 0.05 compared to Group A

Discussion

In the present study, we found that caspase-1 was significantly elevated in children with KD, and at the same time, caspase-1 was further elevated in children with CAL+, confirming the close association between caspase-1 and KD as well as CAL. We first observed the changes of caspase-1 in KD and found that the concentration of caspase-1 in the acute phase of the research group reached 8.73 ±3.71 pg/ml, which was higher than that of the control group (p < 0.001), suggesting that caspase-1 may be involved in the occurrence and development of KD. In addition, we also found that caspase-1 in children in the research group gradually decreased after treatment, which can also support the close correlation between caspase-1 and the progression of KD. In previous studies, caspase family members such as caspase-3 and caspase-9 were also found to be elevated in KD [16, 17], which can preliminarily support our results. Furthermore, through ROC analysis, we found that when peripheral blood caspase-1 expression was greater than 12.62 pg/ml, the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing the occurrence of KD were 50.75% and 89.55%, respectively (p < 0.001), which also suggested the potential of caspase-1 to be a diagnostic index of KD in the future. We speculate that the relationship between caspase-1 and KD may be related to the regulation of pyroptosis. As is well known, pyroptosis is a programmed death that occurs after being stimulated by infectious or endogenous injury-related signals, and its physiological processes are dependent on caspase-1, characterized by rapid rupture of the plasma membrane, DNA fragmentation, and the release of intracellular pro-inflammatory substances such as IL-1β and IL-6 [18]. For KD, peroxidation damage due to increased inflammation in the blood vessels is a key cause of CAL and other related complications [19]. Therefore, caspase-1, which marks an exacerbation of pyroptosis, is also related to the progression of KD. This can also be supported by higher IL-1β and IL-6 in the research group compared with the control group when comparing the levels of inflammatory factors, as well as the positive relationship between IL-1β (r = 0.796, p < 0.001) and IL-6 (r = 0.704, p < 0.001) and caspase-1. The study of Bai et al. mentioned that caspase-1 was significantly elevated during atherosclerosis [20], which could also support the results of the current study.

Subsequently, the further observation of caspase-1 in CAL+ and CAL- children in the research group showed that caspase-1 was further increased in children with CAL+ (p < 0.001). ROC curves showed that the sensitivity and specificity of CAL in the diagnosis of CAL in children with KD were 60.00% and 81.08% (p < 0.001), respectively, further demonstrating the potential application of caspase-1 in KD in the future. Research has shown that ischemic heart disease caused by intimal hyperplasia or thrombotic obstruction is the prime reason for the long-term death of KD complicated with CAL, and that the pyroptosis of vascular endothelial cells, which acts as a protective barrier between blood and vascular walls, predisposes to lipid deposition on the vascular intima and prompts a series of immune responses, leading to the deposition of leukocytes on the vessel wall and resulting in the formation of local thrombosis [21]. This is also hypothesized to be the reason for the increased risk of CAL in KD children following the increase of caspase-1. A study on vascular calcification by Ceccherini et al. found that the inflammatory response of vascular smooth muscle cells could be improved by anti-inflammatory treatment, which included a reduction in caspase-1 levels [22], which is in line with our view. Not only that, by logistic regression analysis, we also found that caspase-1 was an independent risk factor for the development of CAL in children with KD (p < 0.001), which further supports their relationship. Based on these results, we believe that in the future, dynamic monitoring of caspase-1 levels in KD patients may be effective in preventing the occurrence of CAL, which will greatly enhance the prognosis and health of the patients.

Through the above studies, we have preliminarily confirmed the diagnostic efficacy of caspase-1 in KD and CAL, but its specific mechanism of action remains to be clarified and requires further research and exploration. In modern pathological research, it has been confirmed that CAL is caused by the abnormal proliferation of HCASMCs and the formation of plaques and thrombi [23], so we intervene in caspase-1 expression in HCASMCs through abnormal expression vectors to determine its influencing mechanism on CAL. The results showed that after up-regulating caspase-1 expression, the activity of HCASMCs increased, the apoptosis decreased, and the cells were largely arrested in the G0/G1 phase (p < 0.001); silencing caspase-1 expression led to inverse changes in the activity of HCASMCs (p < 0.001). These results indicate that caspase-1 has a stimulating effect on the abnormal proliferation of HCASMCs, and combined with the elevated caspase-1 in KD mentioned earlier, we can preliminarily understand the main mechanism by which caspase-1 participates in CAL. In recent years, caspase-1 has been recognized as a novel biomarker and target for cardiovascular diseases [24], which is due to the discovery of aberrant expression of caspase-1 in chronic heart failure, viral myocarditis, and other diseases in several studies [25, 26], and our findings again argue for the results of these studies. Moreover, the pro-apoptotic effect of silencing caspase-1 on HCASMCs suggests that the molecular therapeutic pathway by silencing caspase-1 expression may become a new treatment option for KD combined with CAL in the future, with great research potential.

However, due to the limited conditions, there are still many limitations to be addressed in this study. For example, further experiments are needed to confirm whether the occurrence of KD causes the increase of caspase-1 or the primary increase of caspase-1 causes KD progression. Besides, the pathways through which caspase-1 participates in KD (such as signal transduction and action pathways) need to be further confirmed. It is also necessary to increase the number of cases in the future to improve the accuracy of caspase-1 in diagnosing KD and CAL. In the follow-up, we will conduct more comprehensive research and analysis to address the limitations mentioned above, providing more reliable references for clinical practice.

Conclusions

Caspase-1 is elevated in KD and shows an excellent diagnostic value for both KD and the occurrence of CAL in KD patients, possibly through promoting the abnormal proliferation of HCASMCs. Caspase-1 is expected to become the key to the diagnosis and treatment of KD in the future, providing a new clinical research direction.