Introduction

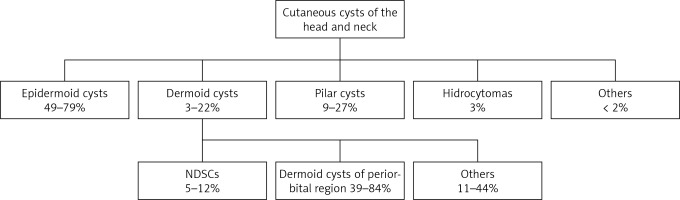

Nasal dermoid sinus cysts (NDSCs) are the most common lesions associated with midline craniofacial anomalies and are composed of two embryonic layers, the ectoderm and mesoderm. NDSCs penetrate the space between the nasal dorsum structures with the additional possibility of anterior cranial fossa involvement [1–3]. NDSCs, also known as nasofrontal dermoid sinus cysts or tracts, are benign lesions that belong to a larger group of dermoid cysts capable of developing anywhere in the human body [4, 5]. Dermoid cysts together with epidermoid cysts, pilar cysts, hidrocystoma, and others form a larger group of cysts termed cutaneous cysts (Figure 1) [4, 6, 7]. NDSCs combined with other midline nasal masses (e.g., nasal gliomas, and encephalocele) occur in 1 : 20 000 to 40 000 live births [2, 4, 8–12]. Moreover, NDSCs represent up to 3% of changes that occur among dermoid cysts in general and up to 12% among head and neck dermoid cysts (Figures 2, 3) [1, 3]. NDSCs may contain dermal appendages (e.g., hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands) without endodermal structures (e.g., respiratory epithelium, thyroid tissue or gastrointestinal cells), which distinguish an NDSC from a teratoma [13, 14]. Although epigenetic changes are the primary cause of NDSC formation, some single familial cases have been reported [1, 8].

Intracranial extension of NDSCs is estimated to represent 4% to 57% of all diagnosed cases [10, 13]. The connection of NDSC with the anterior cranial fossa can lead through the foramen caecum, crista galli, and cribriform plate, or can spread directly from the base of the frontal lobe through the lamina terminalis or optic chiasma [1]. Most NDSCs have an extra-axial extension only to the attaching dura or cerebral falx; however, in extremely rare cases, there is an intra-axial extension with a direct parenchyma connection [1, 15].

The majority of NDSC cases are diagnosed during childhood between 2 and 3 years of life [11, 16–18]. This is primarily due to the presence of characteristic signs and symptoms (e.g., external nose deformation or pathognomonic hair concentration protruding from the sinus canal on the skin above the lesion, often accompanied by periodic ‘cheesy’-like sebaceous and keratin discharge) [10, 11, 13, 18]. NDSCs diagnosed in adulthood are rare, with only two published cases involving the frontal sinus [4, 19–22].

Approximately 39% to 84% of head and neck dermoid cysts are located in the periorbital region [5, 6, 22, 23], most of which are localized in the superior temporal zygomatico-frontal suture, and about 10% are localized in the superior nasal frontal suture [24]. NDSCs with an orbital extension are also described in the literature [22, 25] and their symptoms include swelling in the periorbital region with deteriorating vision and eye displacement (i.e., proptosis, ptosis or diplopia) [19, 20, 22]. Additionally, since limited forehead or upper eyelid swelling may occur, complications of frontal sinusitis should be taken into consideration during the differential diagnosis, especially when patients do not respond to standard treatment [4, 19–22, 26].

A diagnosis of NDSC is based on a clinical examination accompanied by imaging studies and is finally confirmed with histopathological analysis [2, 12, 24, 27]. The preoperative assessment of the NDSC anatomy and central nervous system involvement using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is crucial for preoperative preparation [2, 4, 10–13, 16, 27]. There are specific features in the imaging results which may suggest an intracranial extension, e.g., enlargement of the foramen caecum or bifid crista galli. However, interpretation in paediatric patients compared to adults can be difficult due to the presence of non-ossified structures [11, 27, 28]. Therefore, the surgeon should always be prepared for situations involving an intracranial extension of the dermoid cyst that may be revealed only intraoperatively, despite the extracranial limitation of the lesion in preoperative imaging studies [12].

Dermoid cysts in the nasofrontal region should be differentiated from other pathologies that can present as a mass, fistula, or sinus with similar manifestations. Figure 3 shows the differential diagnosis of NDSCs, such as encephaloceles, teratomas, sebaceous cysts, and hematomas, from fibrosis, lipomas, and fibromas [2, 3, 10, 20, 28]. Treatment of NDSCs is based on the possibility of surgical excision, which depends on the location, size, and intracranial extension of the lesion [2, 16]. Complications of untreated NDSCs include spontaneous local infection with frontal bone osteomyelitis, and abscess formation, which can be incorrectly interpreted as a lacrimal sac abscess when medial canthus swelling is present [10, 18, 22, 29]. Moreover, long-lasting inflammation can lead to deformations of the nasal bones and cartilage, or even atrophy [8, 13]. Recurrent local inflammation associated with NDSC that communicate with the central nervous system can be life-threatening and may lead to meningitis or brain abscess [1, 13].

Here, we present a case of an adult patient with a NDSC affecting one side of the frontal sinus, who was successfully surgically treated with a combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach. Additionally, we reviewed the literature on cases of NDSCs extending to the frontal sinus in adults and the associated methods of treatment. Furthermore, we propose a new classification for dermoid cysts affecting the frontal sinus.

Aim

The main aim of this paper is to demonstrate the clinical, radiological and diagnostic pitfalls of NDSCs affecting the frontal sinus and the comparison with the literature.

Material and methods

Retrospectively collected data was analysed from patient admitted to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Medical University of Warsaw in Poland.

A literature review was performed by a search of the PubMed and Medline database for all relevant English and Polish language studies published from January 1999 to March 2019, using the search terms: “nasal dermoid sinus cyst”, “nasal dermoid sinus cyst in adult”, “surgical management of nasal dermoid sinus cyst”, “dermoid cyst affecting frontal sinus”, “dermoid cyst affecting frontal sinus in adult”, “nasofrontal dermoid cyst”.

Results

Case presentation

A 58-year-old man was admitted to the Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Medical University of Warsaw in Poland, with a periodically recurrent subcutaneous nodule lesion of the nasal dorsum associated with co-discharge from the skin fissures on the nasal dorsum (below the rhinion and in the supratip area) since childhood, without specifying the exact age (Photo 1).

Photo 1

Preoperative pictures of the patient with NDSC involving the external nose. Frontal (A) and lateral (B) view of the external nose demonstrating NDSC located cephalically to the rhinion (arrow)

His medical history revealed that he had been in a car accident in 2012, during which he suffered a multi-organ injury with cervical vertebrae C1-C5 fractures, contusion of the spinal cord at the C4 level and left frontal lobe, complicated by quadriplegia. In 2016, he was successfully treated for Lyme disease and viral meningitis. The patient also underwent several ESS procedures and remained on steroid treatment due to aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP). At the beginning of 2018, he underwent an endonasal rhinoplasty due to the nasal dorsum deformity, which reoccurred about a month later.

During hospitalization, CT revealed massive inflammatory changes in the paranasal sinuses (24 points on the Lund-Mackay score) with partial absence of the nasal and frontal bone on the right side (Photo 2). MRI revealed a 27-mm lesion in the nasal dorsum. The density of the lesion was comparable to adipose tissue. The lesion was communicating with the nasal cavity and frontal sinus without intracranial extension (Photo 3). An endoscopic nasal cavity examination revealed local oedema with polyps and mucous secretion (12 points on the Lund-Kennedy score of endoscopic assessment) [30].

Photo 2

Computed tomography images of the paranasal sinuses: (A) sagittal plane, (B) axial plane, and (C) coronal plane, demonstrating opacification in the paranasal sinuses with partial lack of the nasal and frontal bone on the right side (arrow)

Photo 3

Head magnetic resonance imaging: nasal dorsum lesion communicating with the nasal cavity and frontal sinus without intracranial extension (arrow). (A) Sagittal plane, (B) axial plane, and (C) coronal plane. Note the complete opacification of the paranasal sinuses visible on the axial plane due to the AERD

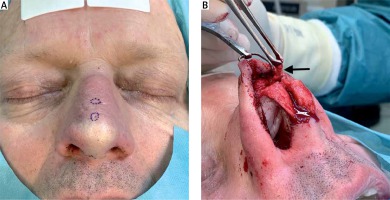

The patient was scheduled for a combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach. During the first stage of the operation, bilateral sphenofrontoethmoidectomy was performed to remove the polyps and reopen all the inflamed sinuses. During the second stage of the operation, a V-incision for the endoscopic-assisted external rhinoplasty approach was performed. Two additional elliptical incisions were made around the NDSC fistulas. The tract of the fistula was dissected (Photo 4). The main sac of the lesion was filled with a ‘cheesy’-like sebaceous and keratin substance lined with dermis, including appendages (i.e., hair) (Photos 5, 6).

Photo 4

Intraoperative images demonstrating preliminary phase of the combined technique of endoscopic- assisted open rhinoplasty with endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach for removal of NDSC. A – Marked elliptical incisions around two fistulas of the NDSC, B – demonstration of the fistula tract of the NDSC (arrow)

Photo 5

Intraoperative image of the combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach for removal of NDSC. The arrow indicates purulent discharge within the fistula sac

Photo 6

Intraoperative image of the combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach for removal of NDSC. The sac of the lesion filled with a sebaceous and keratin ‘cheesy’-like substance lined with dermis, including appendages (hair)

The lesion extended to the lumen of the frontal sinus (Photo 7). The NDSC was dissected and removed completely. The bony surface of the tract was further cleaned using a diamond drill and Draf type 2B frontal recess surgery was performed to extend its ostium. Subsequently, the space after NDSC removal was filled with nasal muscle, adipose tissue of the nasal dorsum, and crushed fragments of nasal septum cartilage. Histopathological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a dermoid cyst with contained dermoid elements. The patient was symptom free at the 12-month follow-up (Photos 8, 9).

Photo 7

Intraoperative image of the combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach for removal of NDSC. A probe inserted through the rhinoplasty cut shows connection to the frontal sinus recess area

Photo 8

Postoperative image at the 12-month follow-up after excision of the NDSC. The lateral view of the external nose demonstrates no signs of external nose deformation or NDSC recurrence

Photo 9

Postoperative endoscopic image demonstrating patent frontal sinus recess with neither pathological discharge nor polyps after combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach for removal of NDSC at the 12-month follow-up

Literature review

PubMed and Medline database searching articles from the last 20 years revealed 5 cases of dermoid cysts involving the frontal sinus (Table I).

Table I

Five previous reports of dermoid cysts involving the frontal sinus in adult patients

| Reference/study | Age | Gender | Dermoid cyst location | Intracranial extension | Surgical method | Follow-up | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post 2005 [4] | 35 | Male | NDSC affecting frontal sinus | No | Local skin incision with excision along fistula canal. External approach to frontal sinus (osteoplastic flap) | 3 years | None |

| Pham 2010 [19] | 28 | Male | Dermoid cyst of the orbit affecting frontal sinus | No | External approach (medial upper-eyelid incision) | No data | No data |

| Patnaik 2012 [21] | 50 | Female | Dermoid cyst of the orbit affecting frontal sinus | No | External approach (unspecified) | No data | No data |

| Gupta 2012 [22] | 28 | Male | NDSC affecting orbit and frontal sinus | No signs of involvement in MRI, but with defect of frontal sinus posterior wall in CT | Local skin incision with excision along fistula canal. Transnasal endoscopic skull base approach to frontal sinus | 8 months | None |

| Splendiani 2016 [20] | 84 | Female | Dermoid cyst of the orbit affecting frontal sinus | Yes | External approach (unspecified) | No data | No data |

Discussion

Here we present: 1) a rare and complex case of NDSC in an adult patient that affected the frontal sinus combined with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps during the course of AERD; 2) an effective method of surgical treatment with a combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with ESS – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach; 3) a literature review on dermoid cysts affecting the frontal sinus and the available dermoid cyst classifications; and 4) proposal of a new classification for a dermoid cyst affecting the frontal sinus.

NDSCs are typically diagnosed and treated during childhood due to characteristic signs and symptoms. The rarity of this disease in adults has been confirmed in several studies [4, 16, 19–22]. During the past 20 years, only 5 cases of dermoid cysts spreading to the frontal sinus have been published, of which only one was a case of an NDSC affecting the frontal sinus [4], 3 cases were dermoid cysts of the orbit affecting the frontal sinus, and one was an NDSC affecting both the frontal sinus and orbit [22] (Table I). According to the embryological theory of NDSC formation, the cyst can spread to the frontal sinus when the dural diverticulum does not regress during frontal and nasal bone fusion [1, 2, 4, 8, 10, 22].

Furthermore, the lack of childhood cases of NDSC affecting a frontal sinus may be associated with the time of frontal sinus development. The appearance of the frontal sinus begins during the second year of life, although the sinus may not be radiologically observed until the sixth year, and growth continues until the second decade of life [31]. This explains the reported case of a bilateral NDSC causing erosion of the frontal bones imitating a Pott’s puffy tumour in a 7-month-old male patient [32]. Since the frontal sinuses had not yet been pneumatized at the time of the diagnosis, frontal sinus involvement may be not possible until adolescence in cases of slower NDSC development [32]. Our presented case affirms this assumption. Additionally, there are cases of NDSCs spreading to other sinuses (i.e., ethmoid cells, maxillary sinus, or sphenoid sinus); however, these cases are extremely rare, with limited data in the literature [3, 23, 33].

Diagnosis of NDSC can be delayed for many years due to the lack of signs of exacerbation [25]. Our patient had all the typical symptoms of an NDSC since childhood; however, a moderate external nose deformity with dorsal exudate was dominated by typical symptoms of CRSwNP during the course of AERD and created conditions for which the correct diagnosis was postponed. To obtain an accurate diagnosis, we performed CT and MRI scans as recommended in the literature. Furthermore, it is extremely important to emphasize that dermoid cysts located in the frontal sinus may mimic CRS complications, which has also been confirmed in previous studies (e.g., Post et al.) [4, 19, 22].

We present a minimally invasive method for the surgical treatment of an NDSC extending to the frontal sinus. A combined technique of endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with ESS – Draf type 2B frontal sinus approach – was found to be an effective method for NDSC excision. This approach ensured the complete removal of the lesion with perfect vision of the operating field while maintaining the aesthetic effect, and without requiring an external approach to the paranasal sinuses.

The appropriate choice of surgical techniques used to remove NDSCs depends on the size, localization, and intracranial extension of the lesion [2, 4, 12, 18]. The rate of recurrence varies from 30% to 100% among NDSCs and a complete excision should be always performed, regardless of the chosen technique [11, 17, 27]. Pollock presented the history of methods used for NDSC excision during the early eighties, beginning with the incomplete removal by drainage or a simple incision with minimal aesthetic complications [34]. Although almost 40 years have passed since this publication, the basic assumptions of NDSC treatment rely on a radical excision using minimally invasive methods. Table II presents a summary of the surgical methods used for NDSC treatment over the past 20 years, depending on the lesion extension.

Table II

Surgical methods used to remove NDSCs depending on the lesion extension

Minimally invasive technique such as open rhinoplasty alone or combined with additional local skin excision of the cyst is an optimal approach for removing NDSC used by many authors with achievement of favourable results, both aesthetically and functionally [10–12, 22, 35]. According to the information presented in Table II, this technique has been widely used for removing NDSCs with both an extracranial [2] and intracranial extradural extension [36, 37]. To maximize the vision of the operation field, some authors have also used endoscopes [2, 9, 12]. For NDSCs with an extracranial and additional intraosseous extension, Miller et al. and Livingstone et al. used an endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty technique to promote better visualization of the entire NDSC sinus tract, similar to the method used in our case [2, 9].

An additional elliptical skin incision is necessary for complete NDSC removal in cases involving opening of the skin of the NDSC sinus tract, which is in accordance with the method used to treat our patient [2, 16, 17, 27, 29]. For smaller lesions, resection using only this method is possible [11, 32]. Moreover, transnasal endoscopic approaches without any skin interference are reserved only for select cases of NDSC without skin involvement, limited to the intranasal space, with or without intracranial involvement [13]. A bicoronal flap and frontal craniotomy is an invasive surgical technique typically used by head and neck surgeons in cooperation with neurosurgeons [13, 24, 29].

Minimally invasive techniques imply a decreased risk of: cerebral damage with neurological deficits; CSF leakage; and olfactory nerve destruction with anosmia [38]. On the other hand, invasive techniques (e.g., craniotomy) are currently indicated less frequently, but continue to be used for very specific cases of NDSC treatment (i.e., extensive intracranial extensions of NDSC) [2]. However, the surgeon’s experience is one of the main factors in determining the choice of technique [24, 39].

Although there are some proposals of dermoid cyst classifications available in the literature, none refer to dermoid cysts with a frontal sinus extension. In Tables III–V we have compiled all of the dermoid cyst classifications presented and published in the literature over the past 80 years. Table III presents the NDSC classifications, Table IV details the classifications of dermoid cysts of the head and neck region, and Table V lists the dermoid cysts of orbit classifications [3, 23, 24, 29, 39–45].

Table III

Previous NDSC classifications

| Study | Year | Study design | Study group | Clinical endpoints | Proposed division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musebeck, Niedzielski [8] | 1968 2004 | Retrospective case series | 5 paediatric patients | ||

| Bradley [42] | 1983 | Retrospective case series | 74 paediatric patients | ||

| Ortlip [29] | 2015 | Retrospective case series | 4 paediatric patients |

| |

| Hartley [3] | 2015 | Retrospective case series | 103 paediatric patients | ||

| Miller [2] | 2019 | Literature review | No information |

|

Table IV

Previous classifications of dermoid cysts affecting the head and neck region

| Study | Year | Study design | Study group | Clinical endpoints | Proposed division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New [43] | 1937 | Retrospective case series | No data | ||

| Pryor [23] | 2005 | Retrospective case series | 49 paediatric patients |

| |

| Al-Khateeb [6] | 2009 | Retrospective case series | 109 adult and paediatric patients | ||

| Prior [39] | 2018 | Retrospective case series | 234 adult and paediatric patients | ||

| Choi [5] | 2018 | Retrospective case series | 32 adult and paediatric patients |

Table V

Previous classifications of dermoid cysts affecting the orbit

| Study | Year | Study design | Study group | Clinical endpoint | Proposed division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavazza [24] | 2011 | Retrospective case series | 30 paediatric patients | ||

| Elbakary and Eldesouky [44] | 2016 | Retrospective case series | 153 adult and paediatric patients |

In Figure 4, we present a new classification for dermoid cysts that affect the frontal sinus, depending on involvement of both the external nose and orbit with or without intracranial extension.

Conclusions

Dermoid cysts affecting the frontal sinus are rare lesions that may mimic complications of sinusitis. Due to their development in the frontal sinus, these lesions are more common in either older children or adults. Therefore, diagnostic CT and MRI are mandatory. The recommended treatment involves a minimally invasive combined double approach using endoscopic-assisted open rhinoplasty with simultaneous ESS as the method of choice for treating NDSCs that affect the frontal sinus. This approach allows for a complete resection of the lesion while simultaneously maintaining aesthetic value for the patient. Furthermore, we present a review of the dermoid cyst classifications, surgical techniques for nasal dermoid cyst removal, and a new classification for dermoid cysts that affect the frontal sinus.