Introduction

Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) is an established treatment modality for early gastric cancer (EGC). Many studies, including prospective randomized clinical trials (RCTs), have proven the benefits of LDG for EGC, including low blood loss, low postoperative pain, early recovery and return to work, and earlier discharge from hospital [1–5]. Several retrospective studies have reported that laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) is a feasible and safe procedure for gastric cancer with the following benefits: less blood loss, earlier postoperative recovery, reduced postoperative complications, and similar lymph node harvesting capacity, compared with open total gastrectomy (OTG) [6–11]. As new techniques for intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy (EJ) have been introduced, totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) has become a widely accepted treatment for cancer of the upper stomach [12–19]. However, laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) has not been supported by randomized control trials, and OTG is still the standard for advanced gastric cancer (AGC) of the upper stomach.

Aim

This study aimed to confirm the safety and feasibility of TLTG using the modified overlap method for the treatment of AGC by comparing it with TLTG for EGC.

Material and methods

We retrospectively collected and analyzed medical records’ data for 149 patients who underwent curative TLTG with the modified overlap method for gastric cancer treatment between March 2012 and December 2018. All procedures were TLTGs with overlap EJ. We evaluated TNM stages using the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines. Pain was measured using a visual analog score (VAS). We evaluated early complications (≤ 30 days after surgery) and late complications (> 30 days after surgery). We also evaluated the methods for managing complications, reoperations, and readmissions. Complications were evaluated according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Numerous clinicopathologic variables were evaluated. We also evaluated these variables in terms of their associations with EGC and AGC. Numerical data are described as means with standard deviations and were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Cross-tabulation analysis was performed using the χ2 test. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. All statistical data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The protocols of this study were approved by the relevant institutional review board (2019-0702).

Surgical anastomosis technique

After TLTG, we performed intracorporeal EJ with the modified overlap method using a 45-mm linear stapler (Photo 1). During EJ, an angle of approximately 45° from the esophagus was ensured (Photo 1 A). After EJ formation, we closed the common opening transversely to prevent narrowing of the anastomosis using a 60-mm linear stapler with three stitches (Photo 1 B). Photo 1 C shows the final view after the completion of the modified overlap EJ. We then performed intracorporeal side-to-side jejunojejunostomy (JJ) using two 60-mm linear staplers approximately 40–45 cm from the EJ.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics of all patients

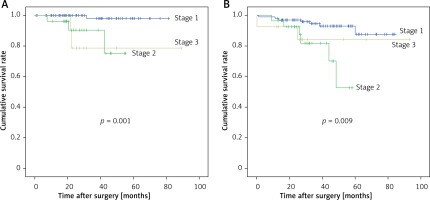

The characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table I. A total of 149 patients who underwent TLTG with the modified overlap method were included, 92 (61.7%) of whom were male, and 57 (38.3%) of whom were female. The mean age of the patients was 60.7 ±11.5 years. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.5 ±3.2 kg/m2. Seventy-four (49.7%) patients had comorbidities, and 31 (20.8%) patients had a history of abdominal surgery (24 had minor surgery, and 7 had major surgery). Thirty (20.1%) patients had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 1, 112 (75.2%) had a score of 2, and 7 (4.7%) had a score of 3. Surgical outcomes and pathologic outcomes are summarized in Table II. The mean operation (procedure) time was 147.7 ±29.8 min. The mean time to first postoperative flatus was 3.7 days. Six (4.0%) patients received perioperative transfusion. The mean peak pain score (VAS) after surgery was 5.0 ±1.8. Patients received a mean of 9.7 postoperative analgesic doses before discharge, with a mean of 2.9 (mean) opioid doses. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 9.9 days. We harvested a mean of 39.6 lymph nodes intraoperatively. Regarding tumor stage, 107 (71.8%) cases were diagnosed as AJCC stage I, 28 (18.8%) as stage II, and 14 (9.4%) as stage III. One (0.7%) patient died of postoperative bleeding. Six (4.0%) cases of tumor recurrence, and 15 (10.1%) late postoperative deaths occurred. Figures 1 and 2 show the recurrence-free survival and overall survival rates.

Table I

Clinical characteristics of all patients (n = 149)

Table II

Surgical outcomes and pathologic results for all patients (n = 151)

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications are shown in Table III. We evaluated early and late complications. A total of 32 (21.5%) patients had early surgical complications, among whom 13 (8.7%) had Clavien-Dindo ≥ III complications. The most common complication was ileus (early 8.1%, late 4.0%). Three (2.0%) patients had EJ site complications, 2 (1.3%) of which were EJ site leakages, with the other (0.7%) being EJ site bleeding. However, EJ stenosis was not noted in any patient. Eight (6.0%) patients had late surgical complications, among whom 6 (4.0%) had Clavien-Dindo ≥ III complications. Among the complications, 24 (16.1%) cases received conservative treatment, 7 cases received interventional treatment, and 8 (5.4%) underwent reoperations. Eight (5.4%) patients were readmitted after leaving the hospital.

Table III

Postoperative complications

| Variable | Early complications, n (%) | Late complications, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound complications | 3 (2.0) | 0 | 3 (2.7) |

| Fluid collection | 7 (7.4) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (5.4) |

| Bleeding | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (2.0) |

| EJ site leak/bleeding | 2 (1.3)/1 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (1.3)/1 (0.7) |

| Duodenal stump leak | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.7) |

| Ileus | 12 (8.1) | 6 (4.0) | 18 (12.1) |

| Pulmonary complications | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 2 (1.3) |

| Cholecystitis | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Total | 32 (21.5) | 8 (5.4) | 37* (24.8) |

| Clavien-Dindo classification: | |||

| I | 6 (4.0) | 0 | 6 (4.0) |

| II | 14 (9.4) | 3 (2.0) | 17 (11.4) |

| IIIa/IIIb | 6 (4.0)/4 (2.7) | 1 (0.7)/4 (2.7) | 7 (4.7)/8 (5.4) |

| IVa/b | 0/1(0.7) | 0/0 | 0/1(0.7) |

| V | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Management for complications: | |||

| Conservative | 21 (14.1) | 3 (2.0) | 24 (16.1) |

| Intervention | 6 (4.0) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (4.7) |

| Reoperation | 5 (3.4) | 4 (2.7) | 8** (5.4) |

| Readmission | 0 | 8 (5.4) | 8 (5.4) |

| Surgical mortality | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

Clinical and surgical outcomes between EGC and AGC

We evaluated outcomes according to their associations with EGC and AGC. The clinical characteristics of matched patients are summarized in Table IV. Between patients with EGC and AGC, there were no statistically significant differences in age, sex BMI, ASA score, comorbidity, or history of abdominal surgery (p > 0.05). The surgical outcomes are shown in Table V. Except for recurrence rate, there were no statistically significant differences in any of the investigated surgical outcomes between patients with EGC and those with AGC (p > 0.05). Table VI shows the surgical complications experienced by patients with EGC and AGC. There were no statistically significant differences in any of the surgical complications, including Clavien-Dindo classification, between patients with EGC and those with AGC (p > 0.05). Additionally, there was no significant difference in terms of the management of complications between patients with EGC and those with AGC (p > 0.05). Finally, the rates of reoperation, readmission, and surgical mortality were similar between the EGC and AGC groups (p > 0.05).

Table IV

Clinical characteristics between early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer

Table V

Surgical outcomes of patients with early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer

Table VI

Postoperative complications of patients with early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer

Discussion

Recently, the incidence of gastric cancer of the upper stomach has increased around the world [20]. Unlike Korea and Japan, more than 80% of gastric cancer patients in most countries worldwide are diagnosed with AGC [21]. Therefore, LTG for AGC is a very important issue. Though LTG is less invasive, a highly complex technique is required for lymph node dissection because of the high risk of bleeding, technical difficulty of anastomosis, and narrow view [8, 22]. While TLTG is widely accepted worldwide, three main issues should be overcome: safety, feasibility, and oncologic outcomes.

The safety and feasibility of LDG for early and advanced gastric cancer were confirmed by two large-scale RCTs in Korea and China [23, 24], and an RCT comparing TLTG with OTG is ongoing. Min et al. reported their 15-year experience of 1483 laparoscopic gastrectomies (including 432 LTGs) for advanced gastric cancer [25]. Grade ≥ III Clavien-Dindo complications accounted for 4.9% of complications occurring within 30 postoperative days. Chen et al. reported a case-matched study dealing with TLTG versus OTG for 122 EGC patients and 126 AGC patients [26]. They showed that postoperative complications were experienced by 18 out of 124 patients who underwent TLTG and 22 out of 124 patients who underwent OTG; this difference was not statistically significant (14.5% vs. 17.7%). The anastomosis-related complications included three cases of anastomotic leakage at the EJ site and 2 cases of stricture in both groups, respectively. Recently, two RCTs investigating only TLTG (and not OTG) were reported [27, 28]. The Chinese Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (CLASS) Group reported the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic spleen-preserving No. 10 lymph node dissection for locally advanced upper-third gastric cancer (CLASS 04) [28]. The investigators reported that 13.6% (33/242) of patients experienced complications within 30 postoperative days, including 0.6% (1/242) who died and 3.3% (8/242) of patients who exhibited grade III or higher complications, according to the Clavien-Dindo classification; 2.9% (7/242) of patients experienced anastomosis leakage. The Korean Laparoendoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) group conducted a prospective multi-center trial of LTG for clinical stage I gastric cancer to determine the safety and feasibility of LTG [27]. The short-term results of the safety and feasibility of LTG (KLASS-03 trial, 179 patients) were reported [27]. The investigators reported that 33 (20.6%) patients experienced complications within 30 postoperative days, including 1 (0.6%) postoperative death, and 15 (9.4%) patients exhibited grade III or higher complications, according to the Clavien-Dindo classification; 5 (3.2%) patients experienced EJ complications. In our present study, among 107 patients with stage I cancer, 21 (21.5%) experienced complications within 30 days without mortality, 9 (8.4%) patients exhibited grade III or higher complications, according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, and only 1 (0.9%) patient experienced EJ complications. Nakauchi et al. reported the results of 92 TLTGs for advanced gastric cancer (54 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy) [29]. They found that the incidence rates for early and late morbidities (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III) were 26.1 and 6.5%, respectively, and that 18 (19.8%) patients experienced EJ leakage. In the present study, we performed 48 TLTGs with the modified overlap method for advanced gastric cancer. Among 48 patients, 10 (20.8%) experienced complications within 30 days, with 1 (2.1%) death; 6 (5.9%) patients exhibited grade III or higher complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification; and 2 (4.2%) patients experienced EJ complications.

Oncologic outcome is another important issue. Unfortunately, no RCTs have investigated oncologic outcomes of TLTG for AGC. Long-term outcomes of total gastrectomy were reported in 2015 [30]. The 5-year overall survival rate was 97% for stage IA, 74.4% for stage IB, 63% for stage IIA, 53.2% for stage IIB, 56.5% for stage IIIA, 32.5% for stage IIIB, and 15.6% for stage IIIC. The 5-year overall survival was 88.3% for T1a, 92% for T1b, 63.3% for T2, 80% for T3, and 32.5% for T4a. Min et al. reported their 15-year experience of laparoscopic gastrectomy for AGC [25]. They reported 5-year overall survival rates, stratified by stage, as follows: stage IB 88.9%, stage IIA 88.7%, stage IIB 84.2%, stage IIIA 71.7%, stage IIIB 56.8%, stage IIIC 45.4%, and stage IV 25%. The overall recurrence rate was 14.4%, which included local recurrence (1.1%) and distant metastases (13.3%). A 2016 report [29] summarized short- and long-term outcomes of TLTG for AGC [29]. The authors reported that the 3-year overall survival rates for pI, pII, and pIII were 100.0%, 93.8%, 72.7%, and 58.7%, respectively (Figure 2), and the 3-year recurrence-free survival rates were 100.0%, 100.0%, 66.7%, and 39.0%, respectively. The Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) annual report includes 208 participating hospitals and 53 retrospectively documented items, including the surgical procedures, pathological diagnosis, and survival outcomes of 13,626 patients with primary gastric cancer. In 2002, the 5-year overall survival rates of the patients, stratified by the JGCA staging system, were 92.2% for stage IA, 85.3% for stage IB, 72.1% for stage II, 52.8% for stage IIIA, 31.0% for stage IIIB, and 14.9% for stage IV. Additionally, the 3-year survival rates were 94.9% for pT1, 87.2% for pT2, 67.9% for pT3, and 40.3% for pT4a. In our study, the 3-year survival rates were 93.5% for pT1, 100% for pT2, 93.3% for pT3, and 63.9% for pT4a. Also, the 3-year and 5-year overall survival rates were 96.1% and 93.0% for stage I, 82.1% and 52.8% for stage II, and 84.4% and 84.4% for stage III, respectively.

This study had some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study performed at a single institution. Second, the number of enrolled patients was relatively small. Third, we did not assess the long-term oncologic outcomes.