INTRODUCTION

In recent years, health-related information has become increasingly accessible through the internet. Online searches offer rapid, cost-free access to a vast array of medical information, making the internet a primary resource for individuals seeking answers to health-related questions globally [1]. By 2023, approximately 67% of the global population (equivalent to 5.4 billion people) were active internet users. This represents a 45% increase since 2018, with an estimated 1.7 billion new users gaining internet access during this period [2]. According to the 2023 results of the Turkish Statistical Institute’s “Household Information Technologies Usage Survey”, 95.5% of households in Türkiye have internet access, highlighting the widespread use of the internet across the country. Furthermore, 87.1% of individuals aged 16 to 74 regularly use the internet, with internet usage increasing annually, demonstrating its integral role in daily life [3]. A multi-center survey revealed that nearly 60% of respondents turn to the internet for information and advice regarding health status, medications, or medical concerns [4]. This easy access to health-related information has significantly improved health literacy and contributed to more informed health decisions. Many individuals report feeling more confident about their health after obtaining information online. However, despite these benefits, internet users are at risk of encountering conflicting, confusing, unreliable, inaccurate, or outdated information [4, 5]. Additionally, one of the most significant disadvantages is its potential to increase health anxiety [6]. This can lead to losing trust in doctors and negatively impact daily functioning [7].

The term “cyberchondria”, a combination of “cyber” and “hypochondria”, has recently been introduced to describe the negative consequences of searching for health information online [1]. Cyberchondria is associated with an increase in health-related anxiety. Moreover, it has been suggested that cyberchondria not only exacerbates anxiety but may also lead to excessive utilization of healthcare services [8]. Individuals often resort to online searches for minor health concerns instead of consulting a physician; however, this behavior can expose them to conflicting information, ultimately prompting them to seek professional medical advice for diagnosis and treatment [9].

Cyberchondria has been investigated in the context of various chronic conditions, including metabolic syndrome, fibromyalgia, COVID-19, and urological diseases [10–13]. However, no studies have explored its impact on allergic diseases, which are among the health conditions most frequently searched online [14]. Moreover, the anxiety induced by researching rarer but potentially life-threatening conditions, such as hereditary angioedema (HAE) or primary immunodeficiencies (PID), on the internet remains unknown.

AIM

This study evaluated cyberchondria levels and their relationship with health anxiety in allergy and immunology patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND POPULATION

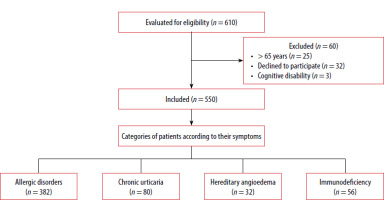

Between January 2024 and June 2024, patients presenting to our allergy and immunology outpatient clinics were prospectively evaluated. The patients were divided into four groups: allergic disorders (allergic asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, allergic conjunctivitis), chronic urticaria, hereditary angioedema (HAE), and primary immunodeficiency (PID) (Figure 1).

INCLUSION CRITERIA

Participants aged 18–65 who use the internet for health purposes and can understand and complete the survey were included.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Participants over the age of 65, those who refused to participate or filled out incomplete surveys, and individuals with cognitive impairments were excluded.

DATA COLLECTION AND INSTRUMENTS

This study used two scales: the Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS-12) and the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI). Additionally, data on demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, chronic illnesses) and diagnosed psychiatric conditions were collected from all patients.

CYBERCHONDRIA SEVERITY SCALE (CSS-12)

McElroy and Shevlin initially developed the 33-item CSS for assessing cyberchondria [15]. Barke et al. developed a short form of this scale [16]. Uzun et al. conducted the Turkish validity and reliability study [17]. This self-reported scale consists of 12 items, each rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The scale does not have a cutoff point; thus, higher scores indicate a higher level of cyberchondria

THE SHORT HEALTH ANXIETY INVENTORY (SHAI)

The SHAI is an 18-item self-report scale used to measure health anxiety [18]. A high score on the scale indicates a high level of health anxiety. Aydemir et al. conducted a reliability and validity study for the Turkish version of the scale [19].

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Since the data followed a normal distribution, the independent t-test was applied for comparisons between two groups, and ANOVA (F test) was used for comparisons among three or more groups. The relationship between participants’ cyberchondria levels and health anxiety was examined using Pearson’s correlation analysis. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

This study included a total of 550 patients, with 390 (71%) being female. The average age of the overall study population was 35.5 ±12.8 years, with an age range of 18–65 years. A total of 382 (69.5%) patients were assigned to the allergic disorders group, 80 (14.5%) patients to the chronic urticaria group, 32 (5.8%) patients to the HAE group, and 56 (10.2%) patients to the PID group.

The mean CSS-12 score was 28.2 ±8.6 in the overall study population, 27.7 ±8.5 in the allergic disorders group, 28.6 ±8.1 in the chronic urticaria group, 33.5 ±8.8 in the HAE group, 28.4 ±8.6 in the PID group (ANOVA, p = 0.003) (Tables 1 and 2). The HAE group recorded the highest CSS-12 score, whereas the allergic disorders group had the lowest CSS-12 score (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1

Comparison of CSS-12 and SHAI scores based on participants’ sociodemographic characteristics

TABLE 2

Post hoc analysis of groups

The mean SHAI score was 17.3 ±7.8 in the overall study population, 16.3 ±7.3 in the allergic disorders group, 18.1 ±7.4 in the chronic urticaria group, 20.6 ±7.4 in the HAE group, 20.9 ±9.8 in the PID group (ANOVA, p < 0.001). The PID group had the highest SHAI score, while the allergic disorders group had the lowest (Tables 1 and 2).

There was no statistically significant difference in CSS-12 and SHAI scores between males and females. However, statistically significant differences in SHAI scores were observed based on education level, chronic illness status, and psychiatric conditions (p = 0.002, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). While SHAI scores were found to be higher in patients with chronic diseases and psychiatric diagnoses, they were observed to be lower in individuals with a high education. No such significance was found in CSS-12 scores (Table 1).

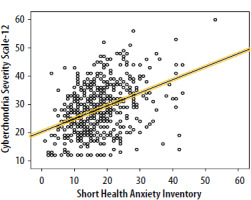

The relationship between the SHAI score (17.3 ±7.8) and the CSS-12 score (28.2 ±8.6) was measured using Pearson correlation. A moderate positive and statistically significant relationship was found between these variables (r(548) = 0.416, p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to assess the severity of cyberchondria among patients attending an allergy and immunology clinic. Our findings revealed that patients with HAE had the highest CSS-12 scores, followed by those with PID. Patients in the allergic disorders group exhibited the lowest scores. Moreover, a positive correlation was identified between health anxiety and the severity of cyberchondria.

Technology is becoming increasingly pervasive in our daily lives, with the internet now serving as a vital resource for seeking health information. While searching for health information online offers convenience, it also poses several risks. Accessing inaccurate or misleading information can lead to heightened anxiety, worry, and fear among patients [1]. Many individuals searching for health information tend to focus on rare and serious medical conditions, rather than more common and benign issues [20]. In one study, 70% of people who initially searched for general, harmless symptoms ended up concentrating on rare and severe conditions [21].

In our study, we observed that the level of cyberchondria is associated with health anxiety. This relationship was particularly pronounced in patient groups with HAE and PID. Patients with HAE typically experience non-pruritic, non-marking episodes of edema affecting the extremities, abdomen, face, or oropharynx, with over half having experienced at least one laryngeal attack [22, 23]. Due to the severity of these complications, patients with HAE may be more inclined to frequently search the internet compared to other groups. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in increased time spent at home, has led to a rise in internet usage [24]. This heightened focus on immune system-related information during the pandemic may have exacerbated the severity of cyberchondria among patients with immunodeficiency. Additionally, the internet features a greater volume of content related to severe illnesses compared to benign conditions. This disparity may contribute to the higher severity of cyberchondria observed among individuals with HAE and PID. This study identified allergic disorders as having the lowest severity of cyberchondria. The heterogeneity within this group could account for its lower CSS-12 scores compared to other groups. Another possible reason is that although allergic diseases affect quality of life, they are less fatal than other disease groups.

A previous study found that health anxiety was elevated in patients with chronic diseases, while cyberchondria severity was more pronounced in those without chronic conditions [25]. In the current study, we observed higher levels of health anxiety in the group with chronic diseases. However, there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of cyberchondria severity.

According to a previous study, cyberchondria was more common among highly educated and affluent individuals than among the general population [26]. Another study reported that individuals with higher socioeconomic status were more likely to seek health information frequently [27]. In contrast, our study found that health anxiety severity was higher among individuals with lower educational levels, while no significant difference in the severity of cyberchondria was observed across educational levels.

Another study conducted in a psychiatric clinic showed that psychiatric problems were associated with cyberchondria and contributed to increased disease burden [28]. It has also been reported that cyberchondria affects depression and quality of life of patients [29]. However, in our study, health anxiety was found to be higher in patients with a psychiatric diagnosis compared to those without a psychiatric diagnosis, whereas no difference was found in the severity of cyberchondria.

Our study had some limitations. First, all data were collected from a single center. Second, the allergic disorders group was heterogeneous, whereas the other patient groups were more homogeneous. This may have influenced our findings.

Although the internet has negative aspects, it is essential in raising patient awareness. For example, a 28-year-old female patient had experienced abdominal pain and angioedema attacks for nearly 20 years without receiving a diagnosis. However, after her mother conducted online research and suspected HAE, the necessary tests were performed, leading to the correct diagnosis [30]. Access to information and education helps patients understand their conditions better and receive higher quality healthcare [31].

CONCLUSIONS

Online access to accurate and reliable health information can enhance patient awareness, but it is essential to recognize the risk of encountering inaccurate or exaggerated information. The increasing severity of cyberchondria highlights a rise in health anxiety and disease burden in affected patients. Addressing these challenges requires a balanced approach, promoting responsible internet use while ensuring that patients receive proper guidance in interpreting health information. Further studies should explore strategies to reduce the negative impacts of cyberchondria and improve patient outcomes.