Introduction

COVID-19 is a new type of virus that first appeared in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, and has spread worldwide [1]. This virus attacks the respiratory tract caused by infection with the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) to be a global pandemic [3]. The impact of COVID-19 is not only on the physical aspect but also the mental aspect of health (such as stress, depression, and anxiety). During the COVID-19 pandemic, people have been more prone to stress, depression, and anxiety.

A large proportion of people in various countries reported that their mental health was adversely affected during the first wave of the pandemic [4]. The prevalence of distress was reported to have increased during the second wave in autumn and winter 2020, which coincided with the re-tightening of restrictions to contain the pandemic. The third pandemic wave in early 2021 (February to May) was less severe than the first and second waves in terms of hospitalizations and deaths [5].

The prevalence of stress, depression, and anxiety as a result of COVID-19 is 29.6%, 31.9%, and 31.9%, respectively [6]. In studies carried out in China in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, the prevalence of severe psychological disorders was 53.8%, moderate-severe anxiety symptoms were reported by 28.8% of the population, moderate-severe depression symptoms were 16.5%, and moderate-severe stress was 8.1% [7]. In Arab studies, 23.6% of the general public reported psychological effects, 28.3% reported depressive symptoms, 24% reported anxiety, and 22.3% reported stress [8]. In studies conducted in Indonesia, as many as 63% of the people experienced anxiety, and as many as 66% reported depression [9]. Early on in the pandemic, research from China, the US, and Europe demonstrated that mental health deteriorated. For example, the UK had a more significant increase in psychological discomfort than was experienced in prior upward trends, with the prevalence rising from 18.9% in 2018-2019 to 27.3% in April 2020, one month into lockdown [5].

There is still little research to identify the determinants of mental health disorders due to COVID-19 in Indonesia. Research conducted by Ilpaj et al. [10] indicated that the mental health impacts of COVID-19 included fear and anxiety, changes in sleeping and eating patterns, feelings of depression and difficulty concentrating, boredom and stress, drug and alcohol abuse, and the emergence of psychotic disorders. Other research shows that COVID-19 causes moderate to severe stress, anxiety, and depression [11].

The impact caused during the COVID-19 pandemic has led to various problems such as economic instability and unemployment. This can bring about an increase in the incidence of stress and anxiety. Identifying the determinants of mental health disorders during the pandemic is very important. These determining factors include age, gender, level of education, experience related to the SARS virus, and fear of infection [12]. Individuals can maintain mental health by identifying the determinants of mental health disorders. Efforts can be made by overcoming anxiety, stress, and depression, always thinking positively, sorting and choosing information related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and fostering good relationships with family and others.

Aim of the work

This study aimed to identify the determinant factors that have been causing mental health disorders in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Search strategy

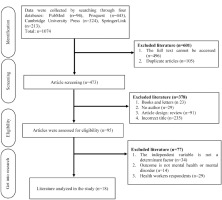

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guide was used in this study. The research was conducted for the articles by utilizing the PubMed, Proquest, Cambridge University Press, and SpringerLink by using the keywords “Determinant Factors”, “Mental Disorder”, “Mental Health”, “COVID-19” and “Corona Virus Diseases 2019” (Table 1).

Study selection

Selections were chosen from research articles published since 2020. The articles focused on people affected by COVID-19 and by mental health problems, including people that remain at risk of mental health problems and people that have suffered from them. Excluded were articles that discuss the physical aspects of the impact of COVID-19 and articles written in languages other than English (Figure 1).

Literature review results

Study characteristics

The determinant factors that have affected people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic can be divided into two aspects, namely, sociodemographic and non-sociodemographic factors. There are 14 studies that state that sociodemographic determinants consist of age, gender, place of residence, education level, and income/economics: Bonsaksen et al. [13], Guo et al. [14], Kantor et al. [15], Makhashvili et al. [16], Mani et al. [17], Mazza et al. [18], Newby et al. [19], Smith et al. [20], Stanton et al. [21], Venugopal et al. [22], Verma et al. [23], Cuiyan et al. [24], Wong et al. [25], and Zoghby et al. [26]. Ten studies describe non-sociodemographic determinants, namely: fear of infection, history of chronic diseases, working from home, family conflict, and lack of family support (Guo et al. [14], Mazza et al. [18], Newby et al. [19], Stanton et al. [21], Venugopal et al. [22], Wong et al. [25], Zoghby et al. [26], Choi et al. [27], Liu et al. [28], and Winkler et al. [29]) (Table 2).

Table 2

Characteristics of the study based on the determinants

| Determinants | Studies |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors: Age Gender Place of residence Education level Income/economics | Bonsaksen et al. [13] |

| Guo et al. [14] | |

| Kantor et al. [15] | |

| Makhashvili et al. [16] | |

| Mani et al. [17] | |

| Mazza et al. [18] | |

| Newby et al. [19] | |

| Smith et al. [20] | |

| Stanton et al. [21] | |

| Venugopal et al. [22] | |

| Verma et al. [23] | |

| Cuiyan et al. [24] | |

| Wong et al. [25] | |

| Zoghby et al. [26] | |

| Non-sociodemographic factors: Fear of infection History of chronic diseases Work from home Family conflict Lack of family support | Guo et al. [14] |

| Mazza et al. [18] | |

| Newby et al. [19] | |

| Stanton et al. [21] | |

| Venugopal et al. [22] | |

| Wong et al. [25] | |

| Zoghby et al. [26] | |

| Choi et al. [27] | |

| Liu et al. [28] | |

| Winkler et al. [29] |

Sociodemographic factors that influence mental health

Age, gender, place of residence, education level, and income / economic factors have affected people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is argued that age is a determining factor in experiencing mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic (OR=-0.03-2.85) as younger people are three times more likely to experience mental disorders than older people [13,14,17,18,23,25] the prevalence of symptom-defined post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Gender is another determinant of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic (OR=0.60-1.70), with women being twice as likely to experience mental disorders as men [13,17,18,23,25]. A place of residence is also one of the determinants of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, on the grounds that people who live in urban areas are more likely to experience mental health problems than people who live in rural areas [15]. Another determining factor is an education level. The studies show that people with higher education are more likely to suffer mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to people with lower education level (OR=0.50-1.26) [15,17,18,23,25] potentially with modifiable risk factors. We performed an internet-based cross-sectional survey of an age-, sex-, and race- stratified representative sample from the US general population. Degrees of anxiety, depression, and loneliness were assessed using the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7). Finally, people earning higher income are three times more likely to experience mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic than people with lower income (OR=0.70-2.95) [13-15,17,18,23] (Table 3).

Table 3

Determinant factors that affect mental health

| Author, year | Design, sample, country | Main findings | Study quality* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonsaksen et al. 2020 [13] | Cross-sectional study 4,527 respondents Norway | Age (OR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.80-0.90), gender (OR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.32-2.16), social support (OR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.43-0.52), economic concern (OR: 2.95, 95% CI: 2.51-3.57) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Choi et al. 2020 [27] | Cross-sectional study 500 respondents Hong Kong | Fear of infection (OR: 2.20, 95% CI: 1.63-2.97), not having a mask (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.50- 2.56), unable to work from home (OR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.13-1.77) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Guo et al. 2020 [14] | Cross-sectional study 2,331 respondents China | Age (OR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.778-1.197), income change (OR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.23-1.84), chronic disease (OR: 1.84, 95% CI: 1.35-2.50), family conflict (OR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.66-2.37) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Kantor et al. 2020 [15] | Cross-sectional study 1,000 respondents United States | Gender (OR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.51-0.89), place of residence (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 0.98-1.79), religion (OR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.63-1.14), occupation (OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.05-2.45), education (OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.24-3.17), | 6/8 (75%) |

| Liu et al. 2020 [28] | Cross-sectional study 898 respondents United States | Fear of infection (OR: 2.87, 95% CI: 1.67-4.94), family support (OR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.32-0.66) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Makhashvili et al. 2020 [16] | Cross-sectional study 2,088 respondents Georgia | Age (p<0.001), economics (p<0.001), occupation (p<0.001) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Mani et al. 2020 [17] | Cross-sectional study 922 respondents Iran | Age (OR: 2.88, 95% CI: 1.81-4.59), gender (OR: 1.74 95% CI: 1.31-2.31), marital status (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 0.55-3.31), education (OR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.75-2.12), economics (OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.61-1.28) | 6/8 (75%) |

| Mazza et al. 2020 [18] | Cross-sectional study 2,812 respondents Italy | Age (OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.02-0.005), education (OR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.355-0.123), gender (OR: 0.63, 95% CI: 1.893-0.445), occupation (OR: 0.719, 95% CI: 0.648-0.011), marital status (OR: 1.087, 95% CI: 0.837-1.003), family support (OR: 0.908, 95% CI: 0.405-0.210), work from home (OR: 1.050, 95% CI: 0.214- 0.313), chronic disease (OR: 1.473, 95% CI: 0.198 0.576) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Newby et al. 2020 [19] | Cross-sectional study 2,812 respondents UK | Age (p=0.00), gender (p=0.00), education (p=0.08), occupation (p=0.030), chronic dis- ease (p=0.08), fear of infection (p=0.03) | 6/8 (75%) |

| Smith et al. 2020 [20] | Cross-sectional study 932 respondents UK | Age (OR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.46-1.49), gender (OR: 2.21, 95% CI: 1.54-3.21), marital status (OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 0.76-1.60), family support (OR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.51-1.15), economics (OR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.40-1.18) | 6/8 (75%) |

| Stanton et al. 2020 [21] | Cross-sectional study 1,491 respondents Australia | Age (p≤0.0010, Gender (p=0.189) marital status (p≤0.001), education (p=0.002), income (p=0.047), chronic disease (p=0.001) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Venugopal et al. 2020 [22] | Cross-sectional study 453 respondents India | Age (p=001), gender (p=0.055), place of residence (p=0.000), marital status (p=0.000), education (p=0.000), occupation (p=0.000), family support (p=0.000), work from home (p=0.039) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Verma et al. 2020 [23] | Cross-sectional study 354 respondents India | Age (OR: 0.746, 95% CI: 0.317-1.757), gender (OR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.767-2.076), marital status (OR: 1.002, 95% CI: 0.452-2.224), income (OR: 1.1, 95% CI: 0.556-2.161), occupation (OR: 1.914, 95%CI: 0.072-3.418), education (OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 0.472-2.840) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Cuiyan et al. 2020 [24] | Cross-sectional study 1,210 respondents China | Age (p=0.006), gender (p=0.004), marital status (p=0.003), family support (p≤0.00), occupation (p=0.004), education (p=0.004) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Winkler et al. 2020 [29] | Cross-sectional study 3,021 respondents Czech Republic | Fear of infection (OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.38-1.99), economics (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.21-1.71) | 6/8 (75%) |

| Wong et al. 2020 [25] | Cohort study 263 respondents Hong Kong | Age (OR: –0.03, 95% CI: –0.08-0.02), gender (OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.30-1.68), education (OR: 0.50, 95% CI: –0.11-1.12), marital status (OR: 0.26, 95% CI: –0.38-0.90), family support (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: –0.16-1.56), chronic disease (OR: 0.38, 95% CI: –0.27-1.03) | 9/11 (82%) |

| Zoghby et al. 2020 [26] | Cross-sectional study 510 respondents (age >18 years) Egypt | Age (p=0.036), gender (p=0.003), place of residence (p=0.001), maritime status (p=0.740), education (p=0.699), working in the medical field (p=0.052), and chronic disease (p=0.011) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

Non-sociodemographic factors that influence mental health

The studies show that people who are afraid of being infected are three times more likely to experience mental health problems than people who are not afraid of being infected (OR=1.66-2.87) [27-29]. People with chronic diseases tend to experience health problems twice as often as people who do not have chronic diseases (OR=1.3-1.84) [14,18,25]. Also someone who works from home is more prone to experience mental health problems compared to someone who works outside of home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, family conflicts are determinant to mental health problems in society during the COVID-19 pandemic. People with less family support tend to experience mental health problems more often during the COVID-19 pandemic (OR=0.04- 0.90) [13,18,20,28,29]the prevalence of symptom-defined post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Discussion of the review results

Sociodemographic factors that influence mental health

The research results show that young people were more likely to experience mental health disorders than older people. This is evidenced by previous research that shows that young adults (18-30 years old) are very vulnerable to experiencing stress because, at that age, they tend to get a lot of information from social media related to COVID-19 [30]. It has been proved that because of the fear that arises, any news or information related to COVID-19, whether verified or not, that is relayed through social media and television will increase panic and fear in the community [27].

The studies also demonstrate that women are more likely to experience mental health disorders than men. Women tend to be more prone to stress, anxiety, and depression, which can also increase post-traumatic symptoms [31]. Also mothers who suffer miscarriages or experience partner violence are at high risk for developing mental health problems. Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, infected pregnant women were giving birth without their husbands/partners accompanying them, and the babies were immediately separated from the mothers to avoid the COVID-19 infection. This has also brought about profound mental health disorders in mothers both in short-term and long-term [31].

The results of the research indicate that people living in urban areas are more likely to experience mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic than people from rural areas. Life in an urban area with a dense population affords less opportunity for social interaction between individuals and can cause an individual to experience loneliness, anxiety, and depression [32]. A crowded environment, noise, and lack of greenery in urban areas can also increase mental health disorders.

The studies [15,17-19,21-26] show that people with higher education experience mental health disorders more than people with lower education. Those with a higher education tended to experience more stress during the COVID-19 pandemic because they had higher self-awareness of their health condition. Not only that, a higher level of education can also be linked to the greater curiosity about health information during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has negatively affected some people’s mental health.

The results of this study [13,14,16,17,20,21] reveal that people who earn higher income are more likely to experience mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to people with lower income. A good economic situation makes it easy to have access to information and to healthcare services. This in turn may lead to mental health problems caused by being exposed to frightening information such as death incidents that occur every day.

Non-sociodemographic factors that influence mental health

The results of the studies show that people who are afraid of being infected tend to experience mental health problems more than people who are not afraid. Feeling afraid and worried was to be expected during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research indicate that people’s mental health has begun to deteriorate since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic which was caused by the fear of being infected with COVID-19 [27] and worrying about infecting their close ones [5,12]. A person who is more worried and afraid of contracting COVID-19 is more likely to have poor mental health [27], as worrying about COVID-19 and feeling depressed can deteriorate a person’s mental health [28]. During the pandemic, people were afraid that they or their family members would fall ill but they did not know yet fully the dangerous effects of the pandemic. In addition, discrimination and stigma related to infectious diseases can make people afraid of being infected, which in turn affects their mental health. Makhashvili et al. stated that people’s lack of trust in the media regarding COVID-19 information could also cause their mental health to deteriorate [16].

The studies [18,19,21,25,26] show that someone who was suffering from a chronic illness during the COVID-19 pandemic was more likely to experience mental health problems in comparison to someone who was healthy. Chronic diseases such as cardiovascular, neurological, and respiratory diseases were usually found in people who experienced mental health disorders during the pandemic. People who suffer from chronic illnesses and think of themselves as having poor health are more susceptible to other diseases, especially COVID-19, resulting in stress on their mental health.

The research results also indicate that people who work from home experience mental health problems more than people who do not work from home. People who stay at home continuously and feel lonely can experience increased anxiety and depression [15]. People experience stress, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) because of being lonely [28]. There has been an increase in poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic among respondents living alone [14]. There is an increase in PTSD symptoms due to several factors, including the lack of social support [13].

Family conflict is a determining factor in mental health [33]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many family conflicts occurred due to termination of employment relationships [34,35]. Families whose members lost their jobs, suffered a loss of income and found it difficult to meet their family’s needs. This is what makes families experience financial distress and become vulnerable to conflict within the family [36]. Positive coping, having good social strengths, and family support can offer protection from stress or mental disorders during COVID-19 [37].

Conclusions

The determinants of mental health disorders found in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic include age, gender, place of residence, income/economics, chronic diseases, family conflict, and family support. It is hoped that the results of this literature review can help nurses determine and control factors that affect mental health in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to achieve good outcomes and to prevent more serious conditions due to COVID-19. In addition, the results of this study can also be a source of literature and information for academic and clinical nursing, as mental health is important for facing not only COVID-19 but also future health threats. Of course, the results of this research depend on the database analyzed, so expanding the database will provide a more comprehensive view. The benefit of this research after the COVID-19 pandemic is the importance of preparing community resilience to face disasters in the future. Community resilience under challenging situations is greatly influenced by factors such as skills in dealing with conflict, the importance of support, and togetherness. The implications of this research can be aimed at regional governments by providing health promotion budgets that focus on community resilience in facing disasters. Meanwhile, nurses and other healthcare professionals (such as midwives, physiotherapists, pharmacists and doctors) are making health promotion plans to improve the community’s mental health. Further research can be developed using experimental methods on how conflict management or social support affects mental health.