Introduction

Mediastinal infection is a persistent and difficult widespread infectious disease caused by secondary complications such as inflammation, damage, or perforation of adjacent organs in the mediastinal space. This disease spreads easily and is often misdiagnosed because of the lack of typical manifestations Current diagnosis, paraclinical investigation and treatment are not easily supported by evidence-based medical research [1, 2].

Mediastinal infection is insidious in the early stage, without typical symptoms; the role of computed tomography (CT) is important. The primary approaches to treatment are to control the origin of infection, control of antibiotic agents, and nutritional help [1–6]. Minimally invasive drainage or surgical interventions are the basic treatment but without consensual standards on the timing of each therapeutic option.

Aim

We report our experience of surgery of descending necrotizing mediastinitis (DNM) through a bicentric retrospective study of patients.

Material and methods

The aim was to highlight the clinical features of mediastinitis, to attempt to define each clinical scenario, responsible pathogens and the medical and surgical treatments through a retrospective study of documented cases of descending necrotizing mediastinitis that were managed at our department of thoracic surgery and otorhinolaryngology of Military Teaching Hospital Mohammed V, from January 2010 to December 2020. Patients included in our study had bacteriological confirmation of DNM after surgery.

Clinical signs and initial infectious site are summarized in Table I. All our patients benefited from a preoperative chest and neck CT allowing us to specify the site and the extent of the infection (Figures 1–4). We adopt diagnostic criteria of DNM defined by Estrera and colleagues including: clinical manifestation of severe oropharyngeal infection (odontogenic, peritonsillar, or retropharyngeal abscesses, Ludwig’s angina, or infection secondary to traumatic pharyngeal perforations), demonstration of characteristic roentgenographic features of DNM, documentation of mediastinitis during the operation or postmortem examination, or both; and establishment of the relation between oropharyngeal infection and development of DNM.

Table I

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with DNM

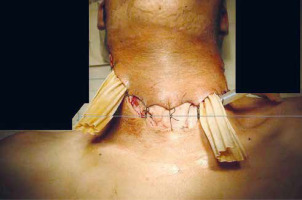

Figure 1

A–C – Transversal views of a rhino cervical scan with multiple beginning infectious collections

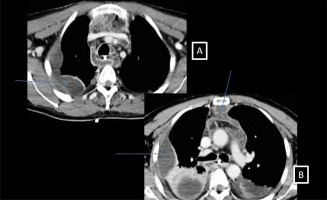

Figure 2

Chest CT view. A – Transversal views of chest CT scan with mediastinal, right pleural extension of mediastinal infection. B – Transversal views of chest CT scan with mediastinal, and bilateral pleural extension of mediastinal infection (arrows)

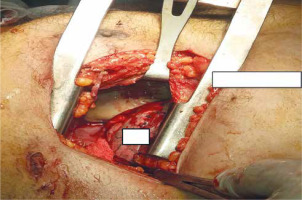

Figure 4

Perioperative view of a right anterior thoracotomy showing a huge collection in the anterior mediastinum

The emergency medical management of these patients included intensive antibiotherapy, and a without delay a surgical procedure to control the polymicrobial infection, through pre-sternocleidomastoid cervicotomy with or without thoracotomy to give access to the different collections of pus in the neck and mediastinum. We technically ensure complete removal of necrotic tissue and we avoid making dissection of non-infected tissue to prevent dissemination of the infection and we particularly emphasize the step of local abundant washing with oxygenated water diluted in saline serum at 0.9%. Complete closure of the surgical cervical wound was forbidden and a washing drainage system was used to allow frequent deep washing by diluted povidone iodine. Secondary wound closure is performed after infection control. For some patients (n = 8) a utility incision in the submandibular area was mandatory to drain the odentogenic abscess. In the case of thoracotomy (n = 5) a double drainage of the mediastinal and pleural space using large size drains (CH 32) and an intrapleural washing system were used.

Results

During a 10-year period at our hospital, 25 documented cases of DNM were treated surgically, 10 from the ORL department and 15 from our department. Patients were aged from 20 to 84 years, with a median age of 41 years, and male predominance, 19 men and 6 women, sex ratio of 3.6. Biological data are in Table II. Surgical approaches are listed in Table III.

Table II

Biological infectious data and isolated germ and used antibiotics

Table III

Surgical approaches performed in emergency treatment of DNM

| Variable | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cervicotomy | 10 (40) |

| Cervicotomy and VATS | 1 (4) |

| Double cervicotomy | 8 (32) |

| Thoracotomy | 5 (20) |

| Re-thoracotomy | 1 (4) |

In the postoperative period, an irrigation-suction system was used on the drains in 15 patients. In one case a rethoracotomy was necessary to remove a residual right pyothorax, and one patient required a tracheostomy.

Because an aggressive approach to post-operative imaging is a key component of this clinical approach a follow-up chest CT performed systematically in the first and second postoperative week was satisfactory without residual collection. Finally, 22 (88%) patients recovered from their mediastinitis. But we regret the death of 3 cases. The cause of death was a non-controlled septic multiorgan failure. Postoperative follow-up during 1 year was uneventful without recurrence.

Discussion

Descending necrotizing mediastinitis (DNM) is an acute polymicrobial infection, stigmatized by delayed diagnosis and usually high morbidity and mortality. It begins in the odontoid or cervical soft tissues and then spreads along the fascial planes to the thorax [6–9]. Inadequate initial control of the source of infection leads to clinical deterioration over the next several hours or days, until respiratory failure or septic shock prompts further investigation. These infectious processes spread rapidly through three cervical fascial planes that serve as a conduit to the mediastinum, or via the retrovisceral space, which connects the retropharyngeal space to the posterior mediastinum accelerated by gravity as well as by the negative intrathoracic pressure generated by normal respiratory excursion. The other two entry points are the viscera vascular space, which descends along the carotid sheath, and the pretracheal space, which is most often involved in postoperative tracheal or thyro-cervical infections. Until 10 years ago, mortality rates in DNM remained high despite the advent of new imaging tactics and the introduction of modern intensive care principles. Mortality rates in retrospective DNM studies have ranged from zero to 83% [1, 2]. Freeman et al. were the first to describe the use of an algorithmic approach to manage DNM [1]. They advocated a broad, multidisciplinary approach with aggressive drainage, including cervical and thoracic debridement, followed by serial cross-sectional imaging to guide future debridement. Over an 18-year period, Freeman et al. treated 10 patients with DNM without any mortality, although they reported marked morbidities [1]. The optimal management of patients with DNM remains controversial [2, 10]. This modified approach involves greater multidisciplinary involvement and aggressively implements 24–72 hourly imaging follow-up with serial debridements based on imaging findings.

The importance of anatomic understanding in the management of the disease and surgical approach is illustrated by our experience and that of others [11–17]. Glucocorticoids prior to admission, anaerobiosis on the initial CT scan, and a pharyngeal focus of fasciitis have recently been defined as independent risk factors for DNM [18]. Late or inadequate treatment is likely to result in a fatal outcome.

DNM was first classified by Endo et al. [5] in 1999 according to the degree of mediastinal extension; infections limited to the area superior to the carina were defined as type I, whereas those extending to the inferior mediastinum (LM) were defined as type II with subdivisions of type IIA for involvement of the anterior LM and type IIB for involvement of the anterior and posterior LM. Sugio et al. [4] proposed a new classification system with an additional type IIC category for infections limited to the posterior SCI. The study found that types I and IIC were more frequently subjected to cervical drainage, whereas types IIA and B were more often treated by thoracotomy. Type II infections had a higher probability of 90-day mortality, with a trend toward better short-term survival for type IIC infections.

The value of early and aggressive imaging for DNM has recently been recognized in the literature, but it is not sufficient to improve outcomes without other measures. In our protocol, routine serial imaging allows us to closely follow the extent of the disease, providing adequate information to achieve rapid and comprehensive source control. Thus, our approach relies on aggressive operative debridements guided by the imaging strategy. The extent of operative debridement in DNM has been the subject of controversy. Some authors have advocated that all mediastinal infections above the carina can be managed primarily by a cervical approach, whereas descent of infection below the carina would require transthoracic drainage [6, 13]. The failure rate of management with isolated transcervical drainage can be as high as 70% [9]. Given the aggressive spread of the disease, other authors have advocated an early, multidisciplinary approach to debridement, regardless of the presence or absence of lower mediastinal involvement [19]. The only previous study to achieve zero mortality reported the use of an initial debridement based on a combined cervical/thoracic approach [1]. In this study, imaging revealed that 59% of patients had an unsuspected site of infection, which led to a more aggressive initial surgical procedure [1, 19]. We strongly recommend a multidisciplinary approach for patients with suspected DNM to rapidly optimize source control and limit disease progression. Key elements of the algorithm include early resuscitation and airway management, urgent surgical exploration and debridement, wide repetitive irrigation and drainage, serial imaging to monitor disease progression, and aggressive serial debridements to achieve optimal source control. Morbidity was minimal other than disease-related morbidity, and this is a crucial feature in the management of patients with DNM, as the application of modern principles of critical care medicine has led to substantial advances in the treatment of the disease.

Some alternative treatments such as immunoglobulins and polymyxin B hemoperfusion treatment can be conducted after surgery. The immunological treatment should be assessed in resistant cases, and intravenous immunoglobulins can be tried in treatment for instable patient [20].