A 74-year-old man was presented to our department with obstructive jaundice due to obstruction of an uncovered, self-expandable metal stent. Previously, he underwent an emergency cholecystectomy due to cholecystitis. He was readmitted to our unit 7 days after the procedure due to obstructive jaundice, fever, and severe upper abdominal pain. His white blood count (WBC) was 22.3 × 109/l, and his C-reactive protein (CRP) was 283.4 mg/l. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. The patient was deemed unfit for major surgery due to his comorbidities: hypertension, ischaemic heart disease with heart failure, and type II diabetes. So, an initial endoscopic approach was chosen. During endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) we discovered a stricture of the common hepatic duct opposite a pair of metallic surgical clips. Many attempts of balloon dilation and plastic stent insertion failed. As a last resort, we successfully inserted an uncovered self-expandable metallic stent (10 × 80 mm); we did not opt for a covered stent due to a high risk of migration. The patient was discharged 5 days after this procedure. After 12 months, the patient was readmitted due obstructive, painless jaundice. A contrast enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination showed a narrowing of the present SEMS lumen. As before, the patient was deemed unfit for surgery, so an endoscopic procedure was preferred.

Several initial ERCPs proved unsuccessful in restoring the patency of the stent. Multiple biopsies and cytology brush sweeps were taken to rule out the presence of a neoplastic lesion. Also, an initial diagnostic cholangioscopy (DPOC) showed only scar tissue obstructing the stent’s lumen.

The patient was qualified for a direct peroral cholangioscopy (DPOC) combined with argon plasma (APC) and radio-frequency (RF) ablation to restore the patency of the biliary stent.

We used an ultra slim gastroscope with a diameter of 5.7 mm (PENTAX Medical, EG17-i10) and a working channel of 2.0 mm. During the procedure we used CO2 insufflation. After performing a re-papillotomy and papilla balloon dilation, we accessed the common bile duct using the “J” manoeuvre. After ascending to the common hepatic duct, the obstructed stent and the scarring of surrounding tissue were visualised (Figure 1). Using an APC probe (Figure 2) in a sweep motion (cranial to caudal), we made about 10 passes, creating a 3 mm wide passage though the stent’s lumen. Next, we used an RFA catheter to further ablate the stent lumen – we used an 18 mm RFA catheter (ELRA, StarMed) and the stent lumen was ablated for 2 min per pass (3 passes made in total to cover the full length of the stricture) with 10 Watts and 80°C (Figure 3). After that, a plastic biliary stent was passed through the metallic stent to prevent restenosis (Figure 4).

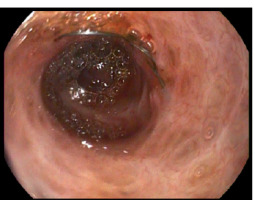

Figure 1

Cholangioscopic view of an uncovered, self-expanding metal stent obstructed by scar tissue. Nitinol weave of the overgrown stent can be seen. During previous procedures multiple biopsies and cytologic brush sweeps ruled out the presence of neoplastic lesions

Figure 2

A 5 fr APC probe (ERBE, FiAPC 1500A) used to ablate the scar tissue obstructing the self-expandable metal stent. APC settings: Forced APC 70 Watt, 1 l/min

Figure 4

A plastic biliary 10 fr 90 mm Amsterdam- type stent passed through the stenosis after its ablation to prevent further narrowing

The plastic stent was removed 3 months after the initial procedure and an occlusion cholangiography confirmed full patency of the self-expandable stent (Figure 5). The patient is still in follow-up (3 years in total) and has remained jaundice and symptom free.

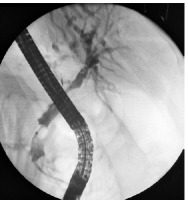

Figure 5

Cholangiography 3 months after the initial procedure. Full patency of the metal stent is visible

To our knowledge, our case is one of a sparce number of cases incorporating cholangioscopy (especially DPOC) with APC or similar ablation techniques [1, 2]. The typical indications for cholangioscopy (both DPOC and single-operator cholangioscopy) are targeted lithotripsy for difficult gallstones, selective bile duct canulation, diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures, and migrated biliary stent removal [3]. Other uses are scarce and often situational. A good example of this is a case of biliary SEMS trimming with APC under cholangioscopic visualisation [4] or a novel approach of restoring the continuity of a bile duct after surgical transection [5].