Introduction

Currently, anal sphincter-preserving surgery is one of the main goals in colorectal surgery. However, defunctioning ileostomy is widely recommended in varying clinical scenarios such as low rectal resection or restorative proctocolectomy [1, 2].

The stoma reversal procedure is associated with perioperative complications classified as grade I or grade II according to the classification of surgical complications proposed by Dindo et al. and may affect up to 40% of patients [3, 4]. Moreover, a recent systematic review showed an overall mortality rate of 0.4% due to stoma reversal procedures [5]. Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common and burdensome complication after stoma reversal (SR) surgery. The incidence rate of SSI after stoma reversal ranged from 2% to 41% [6]. However, introduction of pursestring closure technique to surgical practice resulted in a significant decrease of the surgical site infection rate after the SR procedure [7]. Hsieh et al. in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed that pursestring closure had significantly fewer surgical site infections in contrast to conventional primary closure. However, it was limited to the lack of double blinding and long-term follow-up in the included analyses.

Since negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) was introduced for commercial use in the early 1990s, the strategy of wound management has been revolutionized. The mechanism of action includes reduction of interstitial edema, stimulation of granulation tissue, mechanical wound cleansing, increased microcirculation and tissue oxygenation, decreased wound area and others, which accelerate wound healing [8]. Currently, NPWT is used in varying clinical scenarios, different medical indications and affected areas of the human body. Recently, closed incision NPWT (ciNPWT) was introduced to prevent surgical site infection (SSI). CiNPWT significantly reduced the incidence rate of SSI after sternotomy [9], hip and knee arthroplasties [10], in colorectal patients [11, 12] and Crohn’s disease patients [13], in a groin vascular procedure [14] and spinal surgery [15]. Recently, Poehnert et al. [16] and Uchino et al. independently investigated the impact of ciNPWT on the incidence of surgical site infection after the stoma reversal (SR) procedure [17]. However, the outcomes of those two studies are conflicting. Thus, there is a need for further clarification of the indication of using ciNPWT in the SR procedure.

The risk of transmission of endogenous bacteria into the incision line may result in surgical site infection. Although new strategies and devices were introduced to routine practice such as antibiotic-coated sutures, silver-impregnated dressings, cold-plasma scalpels, and iodine-impregnated skin drapes, the cumulative risk of SSI in stoma reversal procedures is still relatively high.

Aim

The aim of the present study was to investigate the efficiency of portable, no-canister containing incisional negative pressure wound therapy (PICO, Smith & Nephew Ltd, UK) on the incidence rate of SSI after SR surgery.

Material and methods

The study was approved by the institutional bioethics committee at Poznan University of Medical Sciences (trial number 533/14). The study was conducted between May 2015 and January 2017. A total of 30 patients who underwent stoma closure were treated either with NPWT (NPWT group) or standard sterile dressing (SSD group). The study was designed as a randomized, prospective, explorative, cohort observational superiority study.

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the difference in the incidence rate of SSI between ciNPWT and SSD wound care groups.

The secondary objective was to evaluate other surgical site complications (SSC) such as: 1) wound dehiscence rate, 2) seroma and hematoma formation and 3) self-reported pain level as well as to assess the re-admission rate in the analyzed group of patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients included in the study met the following criteria: 1) written consent for study participation; 2) age above 18 years; 3) defunctioning ileostomy created due to either: a) inflammatory bowel disease, b) colorectal surgery, c) familial adenomatous polyposis or d) iatrogenic complications of small/large bowel; 4) stoma closure procedure performed with stoma site approach (without any other incisions); 5) stoma created at least 3 months prior to inclusion in the study.

Patients who participated in another trial or underwent surgery urgently were not included in this study. Another exclusion criterion was the presence of signs of sepsis as well as coagulopathy diagnosed preoperatively.

Study design

After informed consent eligible patients were randomly allocated preoperatively either to the ciNPWT group or the standard sterile dressing (SSD) group by using a closed envelope randomization method. During hospital stay patients were evaluated according to the following schedule – dependent on the dressing changes: 1) ciNPWT: every 3 days or earlier in the case of an unsealed system or layer pad absorbed entirely with wound exudates (a total of three ciNPWT changes were done for every patient; two ciNPWT dressing changes during hospital stay and the third at the time of patient discharge) or 2) SSD: daily dressing changes. The clinical evaluation of SSI signs was performed every day. C-reactive protein (CRP) and the visual analogue scale (VAS) were assessed on the 1st, 3rd and 5th day.

Follow-up was standardized with visits on the 30th day postoperatively in the outpatient clinic or surveyed via phone call to assess any possible complications.

Data inclusion

Data were collected based on the available medical records and surgical charts for age, sex, underlying pathology, time interval from stoma creation to stoma reversal, use of steroids and comorbidities, operative time of stoma closure and length of incision line, time of postoperative hospital stay, readmission and mortality rate.

Diagnosis of SSI

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, superficial SSI was defined in case of skin and subcutaneous tissue infection presenting with pain, redness, heat or swelling at the site of the incision site and/or purulent discharge [18].

Methods of assessment

The surgical wound was evaluated daily in the control group and every third day in the ciNPWT group when the occlusive dressing was changed for signs of SSI (mentioned above). In the case of SSI, the wound was opened at the site of the highest aggravation of SSI and wound exudate was cultured. The incision line was evaluated clinically in regards to seroma or hematoma presence as well as dehiscence. If needed, ultrasound scan examination was made to assess the hematoma/seroma presence.

Postoperative pain was assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS). Briefly, patients specified the amount of pain they experienced on the 10-centimeter line. The pain was graded as follows: 0 – no pain, 10 – unbearable pain. Pain VAS rating was evaluated on the 1st, 3rd and 5th postoperative day.

Patients were tested for CRP level on 1st, 3rd and 5th day postoperatively. Analysis of CRP level was performed with a Cobas 6000 analyser (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) using immunoturbidimetry method. The reference range of CRP level was between 0.01 and 4 mg/l.

Surgical technique

As antibiotic treatment with cefazoline in a dosage of 2.0 g was routinely used 1 h before skin incision, treatment was prolonged over the 24 h following the surgery. All surgical procedures were performed with the stoma site approach. There were no additional incisions or other surgical approach made for the stoma reversal procedure. Following blunt and sharp dissection the ileal loop was completely separated from the abdominal wall. Then, the skin around the intestine was resected, and margins of the intestine were refreshed and sutured using Monosorb 3/0 (Yavo Medical Supplies Manufacturer, Belchatow Poland). In both groups a handsewn end-to-end anastomosis was performed. The peritoneum, as well as the rectus fascia, was closed in layers using PGLA LACTIC 2 (Yavo Medical Supplies Manufacturer, Belchatow Poland). The wound was irrigated with octenidine dihydrochloride (Octenisept, Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Germany) and afterwards rinsed with Ringer’s solution or NaCl and the skin was cleansed with povidone-iodine solution (Braunol, BBraun, Melsungen, Germany).

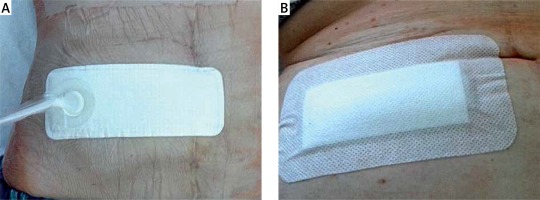

In both groups, the skin was closed primarily with interrupted Nylon 3/0 (Yavo Medical Supplies Manufacturer, Belchatow Poland) in the standard manner. After skin closure, the patient received either ciNPWT dressing or SSD. Standard sterile dressing (gauze and plaster) was applied in the SSD group, whereas in the ciNPWT group, the PICO 10 × 20 cm (Smith & Nephew Ltd, UK) was used (Photo 1). The standard sterile dressing was changed daily by a colorectal nurse and the wound was cleansed with octenidine dihydrochloride solution (Octenisept, Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Germany). CiNPWT dressing was changed every 3 days or earlier in the case of an unsealed system or insufficiency of the soaking pad. Usually, PICO dressing was changed twice postoperatively. At the time of discharge, a third change of NPWT was routinely done.

End-point

The primary end-point of the study was completed on the 30th postoperative day. Appropriate healing was defined macroscopically as proper scar tissue formation at the site of the stoma reversal without signs of inflammation and infection.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro test was used to verify normal distribution. We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction (Mann-Whitney U test) when we compared non-normally distributed variables. Wherever categorical variables were compared, we used Fisher’s exact test, to account for the low number of observations per group. Results with a p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The character of this study involving 30 participants, focused on obtaining first insight of the effects of ciNPWT on stoma-reversal wounds, was preliminary (underpowered due to low cohort size) to provide data for further clinical trials.

Results

Thirty consecutive patients with a median age of 34.5, IQR = 24.5 (range: 19–68) years were enrolled in the study. Patients were treated (n = 15 per group) either with ciNPWT or SSD. The study groups comprised 14 (46.7%) females and 16 (53.3%) males. The female-to-male ratio was 1.14 and 0.67, respectively for ciNPWT and SSD groups. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 22.7 ±4.7 and 25.9 ±4.4, respectively for ciNPWT and SSD wound care (t(28) = –1.98, p = 0.058, d = –0.72). All details of demographic and clinical aspects are summarized in Tables I and II, respectively. Progress in wound healing in both study groups on days 0, 3 and 6 are presented in Photo 2.

Table I

Patient characteristics

Table II

Specifications of perioperative factors

Photo 2

Wound healing on day 0, 3 and 6 after stoma reversal procedure in ciNPWT group (left column) and SSD group (right column). Note the higher wound edema and worse cosmetic effect in the SSD group compared to the ciNPWT group

Ulcerative colitis was the most common underlying pathology for stoma creation in the ciNPWT and SSD group of patients (80% and 53.3%, respectively). Other indications for stoma creation during index surgery were: familial adenomatous polyposis, colorectal cancer and iatrogenic perforation (during colonoscopy). The steroid regimen was discontinued Mdi = 16, IQR = 22 and Mdi = 16.5, IQR = 9.75 months before the stoma reversal procedure for the ciNPWT group and SSD group, respectively (W = 52.5, p = 0.65, 95% CI: –13.99996– 5.00006). There was no statistically significant difference in duration from stoma creation to stoma reversal between the ciNPWT group and the SSD group (MdiciNPWT = 11, IQRciNPWT = 3.5 months, MdiSSD = 6, IQRSSD = 4 months, W = 153, p = 0.09). Smoking was reported by 26% and 20% of patients, respectively, for ciNPWT and SSD groups (p = 1, 95% CI: 0.163–10.234). The mean length of hospital stay before surgery was 6 days (IQR = 2 and Mdi = 4 days, IQR = 3.5), respectively for ciNPWT and SSD (W = 174.5, p = 0.018). There was no significant difference in the mean surgery duration time for ciNPWT (Mdi = 70, IQR = 22.5) and SSD (Mdi = 70, IQR = 20) (W = 127.5, p = 0.55) or in the mean length of incision line (Mdi = 7, IQR = 1.5 and Mdi = 7, IQR = 2) for ciNPWT and SSD, respectively (W = 105.5, p = 0.78). We did not find any significant differences analyzing CRP level assessed on the 1st (W = 84.5, p = 0.41), 3rd (W = 64, p = 0.50) and 5th (W = 77, p = 0.52) postoperative days between study groups. However, VAS assessed on the 1st (MdnciNPWT = 4, MdnSSD = 5, p = 0.027, W = 51.5) and 3rd postoperative days (MdnciNPWT = 2, MdnSSD = 4, p = 0.014, W = 45.5) were significantly lower in the ciNPWT group than in the SSD group. The incidence rate of SSI was reported as 13% (2/15) in the ciNPWT group and 26% (4/15) in the SSD group (p = 0.651, OR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.03–3.73). All patients in the SSD group who developed SSI presented both local and generalized signs of infection. Culture samples were obtained from the wound bed in SSI patients and an empiric antibiotic regimen was administered, which was switched for another antibiotic regimen if necessary based on antibiotic susceptibility testing results. All 6 patients who developed hematoma or SSI required wound drainage and daily dressing changes, which influenced postponed patients’ discharge.

Discussion

In 1971 Turnbull and Weakly described the first loop ileostomy procedure [19]. Since then, defunctioning stomas have been widely used in many clinical scenarios in order to protect distal intestinal anastomosis. The optimal time for stoma reversal has remained debatable and no firm conclusions have been reached. Most authors recommended stoma closure between 8 and 12 weeks after previous surgery [20]. It is believed that such management allows for recovery after previous bowel resection, reduction of intraabdominal adhesions and appropriate scar remodeling. However, stoma reversal is associated with a high risk of intestinal obstruction, anastomotic leak, enterocutaneous fistulae, stoma site hernias and surgical site infection [21].

Bacterial contamination of the skin surrounding the stoma site or spillage of the intestine contents during stoma closure surgery is the key element resulting in surgical site infection [22]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the wound after the SR procedure is classified as contaminated [17]. Moreover, due to long-lasting stoma presence, a higher concentration of skin flora not only at the site of the stoma is observed in this group of patients [23]. Although many strategies and techniques of stoma closure have been proposed, the incidence rate of SSI after stoma reversal is still high and ranged from 2% to 40% [6, 21–28].

As mentioned above as well as our previous experience with the stoma reversal procedure complicated with surgical site infection, we introduced prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis over the 24 h following the surgery. Moreover, based on the recent consensus on wound antisepsis, one of the key indications for using antiseptics prophylactically is a wound at risk of becoming infected [29].

There is a high need to identify and specify risk factors for SSI after stoma reversal, which may influence quality improvement. Liang et al. based on a single institution cohort revealed four independent predictors for SSI after stoma reversal: a history of fascia dehiscence, thicker subcutaneous fat, presence of a colostomy, and African-American race [26]. However, there was no homogeneity of the analyzed group of patients and they differed in terms of type of stoma and surgical approach, simultaneous hernia repair procedure, type of wound closure and others. Thus, firm conclusions should not be drawn and could not be extrapolated to the ileostomy reversal procedure through the stoma site approach. Recently, Chu et al. investigated the predictors for SSI based on 528 stoma reversal patients, recognizing smoking to be a significant predictor of SSI [30]. Based on the latest evidence-based medicine literature review, the most common risk factors for SSI are: obesity, diabetes mellitus, tobacco smoking, ASA score ≥ 3, prolong surgical time, and corticosteroid use [31]. Thus, there is an essential need to assess preoperatively patient and procedure dependent risk for developing SSI and modify the pre- and perioperative strategy regarding the type of wound closure and wound dressing used.

The results of our pilot study are comparable to outcomes presented by Poehnert et al. regarding utility of ciNPWT after the stoma reversal procedure [16]. Although the authors revealed that the postoperative wound infection rate was lower in the ciNPWT group, the difference was not statistically significant, which is consistent with our outcomes. However, in our opinion there are some important differences in study design as well as the type of ciNPWT used by Poehnert et al. and ours which may influence the outcomes. Firstly, Poehnert et al. analyzing the risk factors for wound healing disorders found that a statistically significantly greater number of patients had undergone previous chemotherapy in the standard dressing group (p = 0.024). In our opinion this is a well-defined risk factor of impairment for wound healing and it might have influenced the better outcomes in the ciNPWT group. Secondly, the type of ciNPWT (Prevena incisional wound management system) used by Poehnert et al. is different from the PICO system used in our study. Prevena is composed of Granufoam dressing that may help reduce bacterial colonization. Thirdly, the incorporated canister in the dressing system facilitates greater exudate collection. Fourthly, Prevena delivers negative pressure wound therapy at –125 mm Hg, in contrast to the Pico system which generates –80 mm Hg. Fifthly, the authors did not present patients’ underlying pathologies, which in our opinion may also influence the outcomes.

Based on our experience, we found NPWT to be a useful therapy for abdominal wound management [32, 33] as well as colorectal anastomotic leak [34]. The NPWT mechanism of action is multifactorial and includes: drainage of exudate, decreased tissue edema, contraction of the wound edges, stimulation of neoangiogenesis and granulation tissue, increased blood flow in tissue surrounding the wound and others [30–32]. Thus the NPWT dressing creates the optimal conditions and accelerates wound healing. From a practical point of view in the stoma reversal procedure with ciNPWT we suggest application of interrupted sutures with at least 1.0–1.5 cm intervals. Such application allows for effective absorption of wound excaudate. It is consistent with the recommendations of other authors. Wada et al. recommended preserving the central part of the wound left open using purse string skin closure technique to facilitate wound drainage [35]. It minimizes the blood and serum collection, which may provide an ideal medium for bacterial growth. It was also confirmed that ciNPWT reduced scar thickness formation, and increased tensile strength and mechanical properties of the healed incision line mainly due to increased collagen deposition [36–41].

Introduction of NPWT for the prophylaxis of wound infection in a variety of clinical settings decreased the risk of surgical site infection, wound dehiscence and hematoma/seroma formation. Based on a recent systematic review, decreased incidence rates of SSI, wound dehiscence and hematoma/seroma formation were revealed in the majority of one hundred publications included in the analysis regarding the ciNPWT in various applications [31]. Moreover, a recent meta-analysis showed a 50% reduction in SSI rate when ciNPWT was used compared to the control group [42]. Application of ciNPWT after open colorectal surgery reduced SSI, as has been confirmed independently by many authors [11–13].

Recently, Wierdak et al. demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial that utility of ciNPWT after ileostomy closure in colorectal cancer patients reduces the incidence of wound healing complications and surgical site infection [43]. Such promising outcomes may have significant implications regarding early stoma reversal surgery, even before adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients as suggested by Kłęk et al. [44]. The results are consistent with the study presented by Okuya et al., who confirmed the usefulness of ciNPWT to prevent SSI [45]. None of fifty consecutive colorectal patients who underwent ileostomy closure developed SSI, seroma or hematoma. However, this is a prospective pilot study and a further comparative study is needed to confirm the outcomes. Comparable results were obtained by Cantero et al., who revealed the usefulness of ciNPWT in reducing SSI in the group of SR patients [46]. The results presented by Uchino et al. differed from the above-mentioned studies, as they did not confirm the efficacy of ciNPWT used after the stoma reversal procedure in ulcerative colitis patients [17]. In our opinion, one explanation may be the time of ciNPWT application. In the cited study, ciNPWT was applied on the first postoperative day and maintained up to 14 days. Potentially, the postponed first ciNPWT application with further maintenance for such a long period of time may lead to bacterial colonization and finally to SSI. Secondly, they used the purse-string suture technique for skin closure, which is associated with longer time of wound healing. Moreover, it is important to note that the type of ciNPWT used may also influence outcomes. Based on recent meta-analyses conducted by Singh et al., analysis of foam dressing versus the control showed statistically significant reduction in SSI rates, whereas no significance was revealed comparing multilayer absorbent dressing versus standard dressing [47]. However, the authors indicated some potential factors which may have influenced the outcomes including: differences in patient selection, type of surgery performed, patient and wound comorbidities, level of negative pressure delivered, dressing interface used, and duration of assessment. Thus, in our opinion, a further comparable study is needed to assess the real potential of different type of ciNPWT in the reduction of postoperative wound-healing complications. Based on our study, we did not confirm with statistical significance the superiority of ciNPWT over SSD in regard to SSI rate. One potential explanation may be the small number of patients included in this pilot study. However, this is only a pilot study. Further investigation based on a larger group of patients is needed to establish firmly the benefit for routine application of ciNPWT in stoma reversal patients. Second, the sample group was not homogeneous and the potential risk factors for SSI might vary between patients with different underlying pathologies. Third, no long-term results are presented in the manuscript, as the study is still in progress. Currently, the 30-day follow-up of the patients showed no significant difference between study groups. Based on our previous experience patients who presented with high risk factors for SSI or patients with a high risk procedure may benefit from using ciNPWT. Moreover, the rate of SSI might be underestimated due to varying definitions and considerations. Surgical site infection in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients may be triggered by patient characteristics and comorbidities. Based on a recent expert consensus panel, ciNPWT might be at least suggested or even recommended after the SR procedure due to incision related risk factors (e.g. contamination), operation related risk factors (e.g. open colorectal surgery) and patient related risk factors (e.g. previous corticosteroids usage) [31]. Factors governing colorectal surgical site infection (CSSI) are complicated and multifactorial. Proposed scales estimating the risk of SSI showed that their suitability for clinical practice is still not sufficient [48]. We did not assess the total cost effectiveness of ciNPWT. Although the statistically significant reduction in cost was confirmed in some previous studies, there has been no comprehensive economic analysis of ciNPWT in colorectal surgery. Bonds et al. proved significant total cost savings per patient after colorectal surgery [11]. Chopra et al. reported the economic impact of ciNPWT in high-risk patients after abdominal incisions [49].