Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection is one of the most common comorbidities affecting people living with HIV (PLWH). Although the exact percentage of PLWH who are infected with HCV varies depending on the geographic region and mode of transmission, global HIV/HCV coinfection prevalence is estimated to be 2-4% [1, 2]. Coinfection with HCV is associated with a median life expectancy decrease of 17.3 years and low probability of reaching the age of 65 years [3]. Moreover, HIV/HCV-coinfection accelerates the progression of liver fibrosis, particularly in patients with elevated alcohol consumption or severe immune suppression, which is the case of many HIV-positive individuals [4]. For that reason, PLWH constitute an important population of patients who should be promptly prescribed direct acting antiviral treatment (DAA) targeting HCV infection.

Currently, the pangenotypic DAAs glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (GLE/PIB), sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL) and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir (SOF/VEL/VOX) are approved in most countries for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C (CHC). However, the choice of DAAs in PLWH is often limited due to possible interactions with antiretroviral medications. One of the most commonly used highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) combinations is bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/FTC/TAF), an oral single-tablet regimen (STR) with the indication for the treatment of HIV [5]. It has been proven that coadministration of B/FTC/TAF and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL) is unlikely to induce clinically significant interactions; however, coadministration of B/FTC/TAF with GLE/PIB has not been studied [6, 7].

The aim of this study was to assess the real-life effectiveness and safety of GLE/PIB in HIV/HCV-positive patients treated with B/FTC/TAF.

Material and methods

Patients and treatment

This is an observational, retrospective study based on the EpiTer-2 database, which originally included patients with CHC treated in the years 2015-2023 in Poland with DAA therapies registered in the European Union. Since B/FTC/TAF is a relatively new antiretroviral regimen, the review of the database was focused on patients treated with DAA from 2019 to 2023. HIV/HCV-coinfected patients who received second generation DAA-based therapies during B/FTC/TAF treatment and were followed for at least 12 weeks after the end of treatment were included. The duration of the anti-HCV therapy ranged from 8 to 24 weeks and was dependent on the current guidelines, status of prior treatment, viral load and presence of liver cirrhosis.

Study parameters

The evaluated parameters included: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), HCV genotype, stage of hepatic fibrosis, history of prior anti-HCV treatment, type of DAA regimen and the course of DAA treatment. Hepatic fibrosis was evaluated based on transient elastography (TE) using the FibroScan (Echosens, Paris) device or real-time shear wave elastography (SWE) using the Aixplorer (Supersonic, Aix-en-Provence) device.

Patients were also evaluated in terms of their baseline biochemical characteristics, which included platelet count (PLT), serum creatinine and bilirubin levels, alanine transaminase (ALT) activity, INR and MELD score.

The effectiveness endpoint was the achievement of SVR12 defined as undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after the scheduled end of therapy.

Statistical analysis

All patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in the analysis. Due to the retrospective character of the study no target sample size was planned. The effectiveness analyses were performed on an intent-to-treat (ITT) basis (missing virologic measurements were imputed as treatment failures) and modified intent-to-treat (mITT) basis, which excludes patients with missing data of sustained virologic response (at least 12 weeks after treatment completion). Data were presented as absolute numbers (%) or median and upper and lower quartiles. To compare the differences between groups we used the Mann-Whitney U test for non-categorical parameters (age, HCV viral load, PLT, etc.). For categorical parameters, χ2 distribution, Yates’s correction for continuity and Fisher’s exact test for were used. Statistical analyses were performed with STATISTICA13.0 (StatSoft, USA). Ethical approval was not necessary for this retrospective, observational study conducted in a real-life setting with approved drugs. Patient data were collected and analyzed according to the applicable personal data protection principles.

Results

Comparison of patient characteristics in GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL treated groups

A total of 139 individuals met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 38 were treated with GLE/PIB and 101 were treated with SOF/VEL ± ribavirin (RBV). No significant differences in baseline patient characteristics between the two study groups were observed (Table 1). Patients treated with SOF/VEL were more often treatment-naïve, but the difference was not statistically significant (96.0% vs. 86.8% in GLE/PIB group, p = 0.0629). Prevalence of genotype 3 was higher in the group treated with GLE/PIB (36.9% vs. 21.8% in SOF/VEL group, p = 0.183382), while genotype 1 was more frequent in patients treated with SOF/VEL (55.4% vs. 44.7% in GLE/PIB group, p = 0.348202), but again it did not prove to be statistically significant. The distribution of fibrosis stages was comparable between the two groups, as were gender and median age of the patients. Similarly, no statistically significant differences in baseline laboratory characteristics between study groups were observed.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Comparison of treatment effectiveness in GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL treated groups

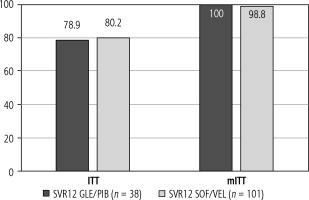

One hundred thirty-nine HIV-HCV-coinfected patients completed the DAA therapy (achieved SVR12, failed to achieve SVR12 or were lost to follow-up) and were included in the analysis. Rates of SVR12 in subjects treated with GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL in ITT analysis were 78.9% (30/38 patients) vs. 80.2% (81/101 patients), respectively. The difference between groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2

Treatment effectiveness in GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL treated groups (ITT analysis)

In a modified intent-to-treat (mITT) analysis, which included only individuals with known SVR12 status (30 patients in GLE/PIB group and 82 patients in SOF/VEL group), rates of SVR12 were 100% (30/30 patients) versus 98.8% (81/82 patients), respectively. The difference between groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Comparison of treatment safety in GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL treated groups

Overall, adverse events occurred in 6.5% of patients (9/139 patients), accounting for 3/38 (7.9%) in patients treated with GLE/PIB and 6/101 (5.0%) in patients treated with SOF/VEL (p = 0.467) (Table 3). The risk of death during treatment and follow-up (2.6% vs. 0.0%, p = 0.273) or liver decompensation (0.0% vs. 0.99%, p = 0.727) was comparable between groups (GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL, respectively). Treatment with-drawal was noted in one individual treated with GLE/PIB (decease during treatment) and in two individuals treated with SOF/VEL (liver decompensation in one case and non-compliance in the second case).

Table 3

Treatment safety in GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL treated groups

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that the real-life effectiveness and safety of GLE/PIB in HIV/HCV-positive patients treated with B/FTC/TAF is similar compared to the SOF/VEL regimen. SVR12 rates reached 78.9% and 80.2% for GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL, respectively, in ITT analysis, and 100% and 98.8%, respectively, in mITT analysis. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to assess the real-life effectiveness and safety of GLE/PIB in HIV/HCV-positive patients treated with bictegravir, a potent integrase inhibitor with antiretroviral activity, that was registered in Poland in 2020.

Most analyses of DAA effectiveness in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection did not investigate the association between type of anti-HIV therapy and SVR. For example, in a study by Rockstroh et al. evaluating GLE/PIB in HCV/HIV-1-coinfected adults with and without compensated cirrhosis, a total of 153 patients were enrolled and the SVR12 rate was 98% [8]. However, although the authors provided detailed information about antiretroviral treatment, they did not analyze its influence on SVR. Other investigators have also reported very satisfactory results of GLE/PIB therapy for treatment of HCV infection in HIV-positive patients, but, similarly, with no precise discussion on the impact of coadministered antiretrovirals [9, 10].

As a consequence, data regarding real life evaluation of treatment effectiveness in HIV-HCV-coinfected patients receiving bictegravir and treated with GLE/PIB are very scarce. In a recently published paper by Gonzalez-Serna et al. the authors made an attempt to compare SVR rates according to the antiretroviral therapy; however, only one case of bictegravir use was noted – the most commonly used regimens included abacavir/lamivudine/dolutegravir (ABC/3TC/DTG), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine/rilpivirine (TDF/FTC/RPV) and alafenamide/emtricitabine/elvitegravir-cobicistat (TAF/FTC/EVG-c) [11]. Of the 132 patients who were HIV/HCV coinfected and started GLE/PIB with evaluable SVR, the overall SVR rate was 126/132 (95.5%) and no differences in relation to ART were observed.

The lack of evidence regarding effectiveness of GLE/PIB in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients treated with bictegravir may be, at least partly, due to controversies related to coadministration of both therapies. According to Liverpool HEP Interactions, since bictegravir is a substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), its concentrations when coadministered with GLE/PIB may increase, but to a modest extent, as glecaprevir/pibrentasvir inhibits P-gp [12]. The product label for Biktarvy (B/FTC/TAF) also indicated that coadministration of glecaprevir may increase bictegravir plasma concentrations and recommended caution [7]. However, in the recent update bictegravir is no longer enlisted among antiretrovirals having important interactions with GLE/PIB [13]. This is in line with present AASLD recommendations related to HCV medication interactions with antiretroviral agents, according to which GLE/PIB should be used with antiretroviral drugs with which it does not have clinically significant interactions, and bictegravir is listed as an example [14]. Also according to updated EASL guidelines no clinically significant interaction can be expected with coadministration of GLE/PIB and bictegravir [15].

Our results seem to confirm these recent recommendation updates, as the safety profile of both anti- HCV regimens when coadministered with B/FTC/TAF was highly satisfactory. Out of all patients treated with GLE/PIB, 97.4% completed the applied DAA treatment regimen compared to 98.0% of patients treated with SOF/VEL (p = 0.619). Patients treated with GLE/PIB did not require treatment modifications and the discontinuation rate was comparable to that observed in the group of subjects treated with SOF/VEL (2.6% vs. 2.0%, respectively, p = 0.620). Similarly, adverse events occurred with the same frequency in patients treated with GLE/PIB and SOF/VEL (7.9% vs. 5.0%, p = 0.467). Finally, also in a recently published update of clinically relevant drug interactions in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy, which included novel drug interactions published from 2017 to 2022, the use of GLE/PIB is not recommended only with efavirenz and boosted protease inhibitors (PIs), and contraindicated with atazanavir (ATV) or atazanavir/rito- navir (ATV/r) regimens [16].

Finally, efficacy of GLE/PIB in treatment-experienced patients, particularly after DAA failure, remains a highly important issue. It is worth noting that in our study GLE/PIB was successfully used in 5 treatment-experienced HIV-HCV coinfected patients. Two of them were previously treated with IFN-based therapies and three were treated with DAAs (one patient received 12 weeks of SOF/VEL, one patient received grazoprevir/elbasvir (GZR/EBR) and one patient received sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV) followed by 12 weeks of SOF/VEL + RBV). HCV genotype distribution was as follows: two patients were infected with HCV G3, one patient was infected with G4, one with G1a and one with G1b. Reasons for not achieving SVR12 included HCV recurrence (n = 2), no response to the treatment (n = 2) and therapy discontinuation due to safety reasons (n = 1). After receiving GLE/PIB two patients were lost to follow-up, while the remaining 3 individuals achieved a total cure and the SVR12 rate in this subgroup reached 100%. Other real-life analyses on the use of GLE/PIB in real-world chronic hepatitis C patients also prove that a history of treatment failure does not negatively affect the GLE/PIB efficacy [17, 18].

The main limitation of our study is the small sample size, which might have influenced the ability to detect statistical significance in the analyses. However, since the combination of GLE/PIB and bictegravir has only recently been officially approved, future research might bring further insight into this issue. In summary, our study shows that real-life results of DAA therapy with GLE/PIB or SOF/VEL did not differ significantly in HIV-HCV-coinfected patients treated with B/FTC/TAF. Both regimens were associated with encouraging SVR12 rates and treatment safety, as well as tolerability, which was also comparable between the study groups.