INTRODUCTION

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a type of urticaria that persists for more than 6 weeks and occurs in the absence of an identifiable provoking factor [1]. It is also an endogenous disease with a strong association with autoimmunity and shares the same immunologic mechanisms as some autoimmune diseases [2, 3].

Autoimmune thyroiditis occupies an important place among the comorbidities of CSU. Studies have shown that there is a strong association between CSU and high levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-thyroid autoantibodies, and therefore the incidence of autoimmune thyroiditis is significantly elevated in CSU patients [4]. Similarly, studies have shown a strong association between CSU and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [5].

In the treatment of CSU, second-generation H1-antihistamines are used as first-line treatment, and this dose can be increased up to 4-fold [6]. CSU cases that do not improve despite increasing antihistamine treatment up to 4-fold are considered resistant to antihistamine treatment [7]. Guidelines for the treatment of CSU recommend the use of the IgE-targeted biologic omalizumab in people with antihistamine-resistant disease [7, 8].

Here, a patient with the autoimmune diseases Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with CSU resistant to antihistamines is presented. The case is of interest since the disease could be controlled with omalizumab and hydroxychloroquine, which are not commonly used together.

CASE REPORT

A 13-year-old girl was referred to an external center 1 month ago with symptoms of widespread pruritus, rash and blistering all over the body, and swelling of the eyes and lips lasting for about 20 min starting at night for the last 3 months. The patient was started on desloratadine 1 × 5 mg/day, but she was referred to our center because there was no improvement in her symptoms despite using desloratadine for 1 month.

When the patient’s medical history was interrogated, it was learned that she had been diagnosed with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in the pediatric endocrinology department 4 years ago because of fainting lasting approximately 3 min and swelling in the neck. She had been using levothyroxine 50 µg tablets since then, and her disease was under control and being followed up. Her family history was unremarkable.

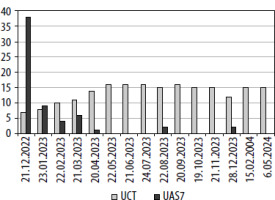

When the patient came to the outpatient clinic, her general condition was good. The physical examination was normal. The patient was found to have no comorbidities other than Hashimoto’s disease. Investigations for CSU were ordered and the dose of antihistamine treatment was increased. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) chromosome granular pattern: 1/132 positive and anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO): 109.4 (N: 0–60 IU/ml) positive. The patient was referred to the pediatric rheumatology department because of Raynaud’s phenomenon and ANA positivity on physical examination. Since her urticaria was not under control in terms of CSU, her antihistamine preparation was changed and later the dose was increased and montelukast was added to the treatment. When the patient came to the follow-up visit 1 month later, it was learned that the diagnosis of SLE had been made by a pediatric rheumatologist, and hydroxychloroquine (200 mg tablet) treatment had been started. After 2 weeks of hydroxychloroquine use and an increased dose of antihistamines, the patient’s symptoms of urticaria and angioedema did not decrease. The patient was then started on omalizumab 300 mg once a month. Before the first omalizumab dose, the patient’s Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) was 38, the Urticaria Control Test (UCT) was 7, and her urticaria was not under control. In the 6th month of omalizumab treatment, UAS7 (0) and UCT (16) were under complete control (Figure 1). The dose of omalizumab was reduced from 300 mg/month to 150 mg/month in the 9th month due to case reports in the literature showing the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine for urticaria by suppressing inflammation. After completing omalizumab treatment for 12 months, omalizumab treatment was terminated by administration of 150 mg 3 times at 4-week intervals, then 3 times at 6-week intervals, then 3 times at 8-week intervals. The patient, who is in the 4th month without omalizumab treatment, is receiving hydroxychloroquine and levothyroxine treatment and no urticarial plaques occur. The patient continues to be followed up and remains under control in terms of CSU. (Consent was obtained from our patient for this presentation.)

DISCUSSION

CSU is a common disorder characterized by the occurrence of widespread erythema, rash, and sometimes angioedema almost daily for more than 6 weeks [1, 9]. Studies suggest that more than half of CSU cases are thought to be due to an autoimmune mechanism, specifically the production of autoantibodies against the high-affinity immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor [2, 3, 9]. These patients often also suffer from autoimmune diseases, e.g. thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, celiac disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, and this greatly reduces the quality of life of the patients due to the occurrence of comorbidities associated with these diseases [9]. Infectious diseases such as COVID-19 and vaccines developed against them may also play a role in the development of CSU, and it is also known that infectious diseases sometimes trigger attacks of CSU [10].

Urticaria, including CSU, is found to be more common in cases with thyroid autoimmunity than in controls. CSU symptoms might improve in response to therapy with thyroid medications. Pathophysiologic mechanisms in CSU cases with thyroid autoimmunity may include IgE, immune complexes, and complement against autoantigens [11]. In most studies, comorbidity rates are ≥ 1% for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and celiac disease, ≥ 2% for Graves’ disease, ≥ 3% for vitiligo and ≥ 5% for pernicious anemia and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Anti-thyroid and antinuclear antibodies are the most common autoantibodies associated with autoimmunity in CSU [12]. Furthermore, the availability of markers (antinuclear and/or anti-thyroid antibodies) for autoimmune diseases has been linked with non-response to omalizumab in CSU cases [13, 14].

While autoimmunity is thought to be a common cause of CSU, often associated with autoimmune thyroiditis [15], its link to other autoimmune disorders such as SLE has not been sufficiently investigated. IgG- and IgE-mediated autoreactivity suggests similarities in the pathogenesis of CSU and SLE, linking inflammation and autoimmunity with the activation of complement and the coagulation system [16]. In a study of 852 cases of childhood-onset SLE, this particular cutaneous manifestation was found to occur predominantly at disease onset and was related to moderate/high disease activity of SLE without major organ involvement [17].

In one study, omalizumab add-on therapy was significantly more likely to be associated with a complete response compared to hydroxychloroquine. In patients who did not respond fully to add-on interventions, 65% and 62% subsequently achieved a complete response to omalizumab and hydroxychloroquine, respectively. As a favorable safety profile is known, hydroxychloroquine is being considered as an adjunctive therapy for refractory CSU [14, 18]. In the association of CSU and autoimmunity, especially when associated with autoimmune thyroiditis, where urticaria is refractory to antihistamine therapy [13, 14], and the addition of an immunosuppressive agent such as hydroxychloroquine fails to control the symptoms of CSU in these patients due to their autoimmune disease, concomitant use of omalizumab, as in our case, may be beneficial [19, 20].

CONCLUSIONS

When the addition of hydroxychloroquine fails to control the symptoms of CSU in patients with CSU and autoimmunity coexisting and resistant to antihistamines, it may be beneficial to use omalizumab simultaneously as in our case. In particular, in addition to breaking the resistance of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease to treatment in this way, this case also demonstrated that omalizumab and chloroquine can be used safely together. Patients with CSU, especially adult women, with a positive family history and genetic predisposition for autoimmunity, are at risk for autoimmune disease and should be screened for signs and symptoms [12].