Introduction

Benign biliary stricture (BBS) is defined as any narrowing along the extrahepatic bile duct with less than 75% diameter of unaffected region [1]. Most cases result from the 2 leading pathogeneses: iatrogenic biliary injury and inflammation damage [2–4]. The condition of iatrogenic biliary injury includes open/laparoscopic cholecystectomy, duct-duct anastomosis after liver transplantation (LT), etc. [4–7]. Inflammation damage is mainly from chronic pancreatitis (CP) and primary sclerosing cholangitis [3, 4]. The incidence of BBS is about 1% for open cholecystectomy, 0.23–0.42% for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, 3–46% for CP, 5–15% for deceased LT, and 28–32% for living-donor transplantation [8–12]. BBS may lead to elevation of serum bilirubin, impairment of liver function, and bacterial growth in the biliary tree. If BBS is not recognized in time and managed properly, these patients can suffer from even worse prognosis because of life-threatening complications such as secondary biliary cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and cholangitis [4, 13]. Therefore, every patient with BBS should receive aggressive treatment to release biliary obstruction effectively.

Currently, endoscopic intervention with stent implantation has been widely adopted for the treatment of BBS (Photo 1) [4]. With accelerated development of biomedical materials, endoscopic stents are continuously evolving, which includes multiple plastic stents (MPSs), fully covered self-expanded metal stents (FCSEMSs), and biodegradable biliary stents (BDBSs), et al. [4]. Among them, MPSs are the most used because of their cheap price, low technical requirements, and acceptable long-term results. However, this kind of stent requires repeated interventions to maintain its therapeutic effect, increasing the incidence of operation-related complications, such as pancreatitis, haemobilia, and abdominal pain [14]. FCSEMSs are another kind of stent with extensive applications. Previous studies have reported that a single FCSEMS is able to provide a radial dilation similar to that of three 10F plastic stents, and thus free from the trouble of frequent interventions [1]. The main drawback of FCSEMSs is frequent occurrence of stent migration (4–41%), often resulting in treatment failure [6]. BDBSs are a relatively new kind of stent, and they are reported to have a similar radial expansion force with FCSEMSs. This kind of stent is biodegradable, and so does not need to be removed specially [15, 16]. The main drawback of BDBSs is that they may degrade prematurely, failing to provide adequate support for expanding the narrowed biliary tract [16].

Aim

Up to now, several meta-analyses have been reported about different stents in the application of malignant biliary stricture. However, a systematic study comparing the efficacy of these stents in endoscopic treatment of BBS is still unavailable. Given the above descriptions, every stent has its pros and cons, and the selection is still controversial. Here, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify the roles of 3 common stents (MPSs, FCSEMSs, and BDBSs) in BBS management.

Material and methods

Search strategy and study selection

Two authors systematically searched the PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Wiley Library databases for studies published from 1 January 2010 to 12 August 2020, by using the following search terms: BBS, benign biliary stenosis, stents. A manual search through the reference of included studies was also carried out to identify the potentially relevant studies.

The studies enrolled in this meta-analysis were required to be randomized controlled trials (RCTs), case-controlled trials (CCTs), cohort studies, or case series studies, which met the following criteria: (1) studies including patients with BBS and treated with one of the types of stents (MPSs, FCSEMSs, or BDBSs) using endoscopic or percutaneous insertion; (2) studies carried out on humans; and (3) studies written in English. The exclusion criteria were: (1) case reports; (2) studies including minors; (3) studies including populations suffering from other complications, such as cystic duck leak or biliary leakage; and (4) unpublished data or data published in abstract form only.

Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted all relevant data from included studies, including publication year, study design, participant characteristics, stent types, implant methods, and follow-up duration. The primary outcome was the clinical success rate, defined as no record of unscheduled interventions, stricture relapse, or change in treatment strategy during the follow-up time. The secondary outcomes included technical success rate, treatment success rate, time to recurrence, adverse events, and intervention frequency. Technical success referred to stents that were successfully implanted at the final cholangiography and then removed successfully. Treatment success referred to BBS that was resolved at stent removal demonstrated by cholangiography or hepatic functional test.

Quality assessment

The criteria used to assess the quality of RCTs are described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Intervention [17]. The risk of bias from CCTs, cohort studies, and case series studies was assessed based on the Newcastle Ottwan Scale (NOS) [18]. Two reviewers independently performed the quality assessment, and all disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

The pooled estimate and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated by using a random effects model. The proportion was calculated for dichotomous variables, as well as the mean value for continuous outcomes. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed with the I 2 statistic and χ2 test. The result of the I 2 statistic ranged from 0% to 100%, and we considered I 2 over 50% as a high degree of heterogeneity. Analysis was done by using Stata 16, in which p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Literature search

According to the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified a total of 1148 potentially relevant articles in the present meta-analysis. After removal of duplicates, 880 studies remained. After screening the titles and abstracts, 832 irrelevant studies were excluded. After evaluating the full text of the remaining studies, 28 studies were eligible for this meta-analysis. We added 1 relevant study after review of the reference list, and a total of 29 studies (1 RCT, 1 CCT, and 27 case series studies) were included. We divided the RCT and CCT (each containing 2 kinds of stents) into 2 separate studies individually, and the final number of included studies was 31. The selection process was recorded to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

The 31 included studies, with 1604 patients, were published from 1 January 2010 to 12 August 2020. These participants were divided into 3 groups according to the stent type: 7 studies with 363 patients used BDBSs, 19 studies with 965 patients used FCSEMSs, and 5 studies with 276 patients used MPSs. The main characteristics of included studies are shown in Table I [19–36]. Of these studies, 20 were prospective studies, and the others were retrospective studies. The stents were implanted by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in 25 studies and by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) in the others.

Table I

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Design | Patient (n) | Mean age [years] | Gender (F/M) | Pathogenesis (n) | Stent | Technique | Follow-up [month] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | Prospective | 159 | 61.5 | 54/96 | Post cholecystectomy (38) Post hepaticojejunostomy (26) Cholecystitis (23) | BDBSs | PTC | 45.4* |

| Battistel 2020 [20] | Retrospective | 18 | 58.3 | 5/13 | Liver transplantation (18) | BDBSs | PTC | 27.2* |

| Siiki 2018 [15] | Prospective | 6 | 62.5 | 4/2 | Chronic pancreatitis (2) Open aetiology (4) | BDBSs | ERCP | 21* |

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | Retrospective | 10 | 60 | 1/9 | Liver transplantation (10) | BDBSs | PTC | 23* |

| Mauri 2016 [21] | Retrospective | 107 | 59 | 46/61 | Cholelithiasis (59) Duodenocephalopancreatectomy (17) Bile duct reconstruction (12) | BDBSs | PTC | 23# |

| Mauri 2015 [22] | Retrospective | 59 | 56.8 | 24/35 | Bile duct reconstruction (3) Post cholecystectomy (2) Duodenocephalopancreatectomy (2) | BDBSs | PTC | 23.2# |

| Giménez 2016 [23] | Prospective | 13 | 38.7 | 9/4 | Hepaticojejunostomy stricture (13) | BDBSs | PTC | 20# |

| Sato 2020 [24] | Prospective | 30 | 63 | 11/19 | Living-donor liver transplantation (13) Hepaticojejunostomy stricture (12) Post cholecystectomy (2) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 15.6* |

| Poley 2020 [25] | Prospective | 41 | 56.7 | 7/34 | Liver transplantation (41) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 57.3* |

| Tringali 2019 [26] | Prospective | 18 | 53.9 | 12/6 | Post cholecystectomy (18) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 60* |

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | Prospective | 118 | 52.1 | 20/98 | Chronic pancreatitis (118) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 58* |

| Wu 2017 [6] | Retrospective | 32 | 52 | 7/25 | Post cholecystectomy (8) Liver transplantation (24) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 43* |

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | Prospective | 43 | 58.3 | 10/33 | Chronic pancreatitis (24) Anastomotic stricture (7) Surgical bile duct injury (4) | FCSEMSs | PTC/ERCP | 15* |

| Aepli 2017 [10]0 | Retrospective | 31 | 56 | 12/19 | Liver transplantation (31) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | NM |

| Cote 2016 [1] | Prospective | 57 | 54.5 | 19/38 | Liver transplantation (37) Chronic pancreatitis (18) Other postoperative injury (2) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 12* |

| Chaput 2016 [28] | Prospective | 92 | 54.4 | 24/68 | Chronic pancreatitis (43) Liver transplantation (36) Post biliary surgical procedural (14) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 12* |

| Walter 2015 [29] | Prospective | 38 | 53 | 14/24 | Chronic pancreatitis (24) Postsurgical stricture formation (7) Papillary stenosis (4) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 9* |

| Saxena 2015 [3] | Retrospective | 123 | 62 | 53/70 | Biliary calculi (37) Chronic pancreatitis (30) Liver transplantation (16) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 18.5# |

| Hu 2014 [30] | Prospective | 45 | 52.3 | 9/36 | Liver transplantation (30) Postoperative stricture (13) Chronic pancreatitis (2) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 18.9# |

| Wagh 2013 [11] | Prospective | 23 | 60.6 | 13/10 | Chronic pancreatitis (14) Liver transplantation (4) Idiopathic (4) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 18.8* |

| Ryu 2013 [31] | Retrospective | 41 | 55 | 14/24 | Chronic pancreatitis (15) Gall stone-related disease (19) Surgical procedures (4) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 10.2# |

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | Retrospective | 133 | 59.2 | 55/78 | Chronic pancreatitis (44) Liver transplantation (35) Gallstone-related disease (28) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | NM |

| Poley 2012 [32] | Prospective | 23 | 57 | 11/12 | Chronic pancreatitis (13) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (6) Open cholecystectomy (3) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 15* |

| Moon 2012 [33] | Prospective | 21 | 61.7 | 8/13 | Chronic pancreatitis (6) Postoperative (8) Others (7) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 13.8* |

| Park 2011 [34] | Prospective | 43 | 60 | 20/23 | Chronic pancreatitis (11) Biliary stone (26) Liver transplantation (2) | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 4* |

| Hu 2011 [12] | Prospective | 13 | 51.2 | 3/10 | NM | FCSEMSs | ERCP | 12.1# |

| Costamagna 2020 [8] | Retrospective | 154 | 53 | 87/67 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (101) Open cholecystectomy (53) | MPSs | ERCP | 11.1# |

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | Prospective | 10 | 56.9 | 0/10 | Chronic calcifying pancreatitis (10) | MPSs | ERCP | 20.6# |

| Canena 2014 [36] | Prospective | 20 | 47.7 | 14/6 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (18) Open cholecystectomy (2) | MPSs | ERCP | 44* |

| Wu 2017 [6] | Retrospective | 37 | 51 | 10/27 | Post cholecystectomy (9) Liver transplantation (28) | MPSs | ERCP | 43* |

| Cote 2016 [1] | Prospective | 55 | 56.7 | 17/38 | Liver transplantation (36) Chronic pancreatitis (17) Other postoperative injury (2) | MPSs | ERCP | 12* |

Quality assessment

We assessed the qualities of included studies using the NOS. The items derived from this scale included 5 questions, representativeness of samples, accuracy of diagnosis, duration of follow-up, integrity of reported date, and ascertainment of outcome. The study was awarded 1 point for meeting each question, and scores of < 3, 4, and 5 corresponded to low, moderate, and high quality [37, 38]. The quality assessment results of 31 included studies are shown in Table II. Sixteen studies were high, 13 studies were moderate, and 2 were low quality.

Table II

Results of quality assessment

| Study | Question 1 | Question 2 | Question 3 | Question 4 | Question 5 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battistel 2020 [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Siiki 2018 [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Mauri 2016 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Mauri 2015 [22] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Giménez 2016 [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Sato 2020 [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Poley 2020 [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Tringali 2019 [26] | Yes | yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Wu 2017 [6] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Aepli 2107 [10] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Low |

| Cote 2016 [1] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Chaput 2016 [28] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Walter 2015 [29] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Saxena 2015 [3] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Hu 2014 [30] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Wagh 2013 [11] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Ryu 2013 [31] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Low |

| Poley 2012 [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Moon 2012 [33] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Park 2011 [34] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Hu 2011 [12] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Costamagna 2020 [8] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Wu 2017 [6] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Cote 2016 [1] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Canena 2014 [36] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

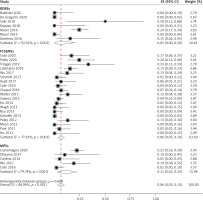

Clinical success

Thirty included studies reported the clinical success rate. From the result of this meta-analysis, as shown in Figure 2, the clinical success was most likely to be achieved when using BDBSs (0.76, 95% CI: 0.71–0.80). The pooled clinical success rate of MPSs was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.63–0.74), which was higher than that of FCSEMSs (0.66, 95% CI: 0.60–0.72). The heterogeneity was evaluated as low for BDBSs (I2 = 0.00% and p = 0.74), high for FCSEMSs (I2 = 65.82% and p < 0.001), and low for MPSs (I2 = 0.00% and p = 0.62). The high heterogeneity of the FCSEMS group might relate to the inclusion of 3 studies (Poley 2020, Moon 2012, and Lakhtakia 2019). In Poley 2020, the stents were scheduled to be removed at 4–6 months (median: 153 days) after implantation, obviously shorter than other studies. In Lakhtakia 2019, 62 patients were lost to follow-up, accounting for a large proportion of included samples (52.6%). In Moon 2012, the used stents had a convex margin at both ends, somewhat different from common FCSEMSs. After exclusion of these 3 studies, the lever of heterogeneity became low (I2 = 22.24% and p = 0.21), but the pooled clinical success rate of FCSEMSs was little changed (0.67, 95% CI: 0.63–0.71) (Figure 3).

Adverse events

All 31 included studies reported the adverse events caused by the inserted stents, and the detailed information is summarized in Tables III and IV. From the result of this meta-analysis, shown in Figure 4, the BDBS group showed the lowest overall incidence of adverse events (0.31, 95% CI: 0.12–0.54), followed by the FCSEMS group (0.40, 95% CI: 0.31–0.50), and MPS group (0.46, 95% CI: 0.31–0.61). Due to the wide variation of categories of reported adverse events among included studies, the heterogeneities in all 3 groups were high, as expected (I2 = 92.71% and p < 0.001 for BDBSs, I2 = 88.28% and p < 0.001 for FCSEMSs, I2 = 76.54% and p < 0.001 for MPSs). Therefore, we further performed a subgroup analysis according to 4 common adverse events, including abdominal pain, cholangitis, pancreatitis, and stent migration.

Table III

Summary of common adverse events

| Stent | Adverse event | Study | Patient (n) | Event (n) | Incidence | Pooled date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDBSs | Abdominal pain | Battistel 2020 [20] | 18 | 0 | 0.00% | 3.03% |

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | 150 | 7 | 4.67% | |||

| Siiki 2018 [15] | 6 | 2 | 33.33% | |||

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | 10 | 1 | 10.00% | |||

| Mauri 2016 [21] | 107 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Mauri 2015 [22] | 59 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Giménez 2016 [23] | 13 | 1 | 7.69% | |||

| Cholangitis | Battistel 2020 [20] | 18 | 0 | 0.00% | 8.54% | |

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | 150 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Siiki 2018 [15] | 6 | 3 | 50.00% | |||

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | 10 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Mauri 2016 [21] | 107 | 26 | 24.30% | |||

| Mauri 2015 [22] | 59 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Giménez 2016 [23] | 13 | 2 | 15.38% | |||

| Pancreatitis | Battistel 2020 [20] | 18 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.83% | |

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | 150 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Siiki 2018 [15] | 6 | 1 | 16.67% | |||

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | 10 | 1 | 10.00% | |||

| Mauri 2016 [21] | 107 | 1 | 0.93% | |||

| Mauri 2015 [22] | 59 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Giménez 2016 [23] | 13 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Stent migration | Battistel 2020 [20] | 18 | 0 | 0.00% | 2.20% | |

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | 150 | 5 | 3.33% | |||

| Siiki 2018 [15] | 6 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | 10 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Mauri 2016 [21] | 107 | 2 | 1.87% | |||

| Mauri 2015 [22] | 59 | 1 | 1.69% | |||

| Giménez 2016 [23] | 13 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| FCSEMSs | Abdominal pain | Sato 2020 [24] | 30 | 0 | 0.00% | 5.28% |

| Poley 2020 [25] | 41 | 4 | 9.76% | |||

| Tringali 2019 [26] | 18 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | 118 | 9 | 7.63% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 32 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | 43 | 1 | 2.33% | |||

| Aepli 2017 [10] | 31 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 57 | 8 | 14.04% | |||

| Chaput 2016 [28] | 92 | 4 | 4.35% | |||

| Walter 2015 [29] | 38 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Saxena 2015 [3] | 123 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Hu 2014 [30] | 45 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Wagh 2013 [11] | 23 | 1 | 4.35% | |||

| FCSEMSs | Abdominal pain | Ryu 2013 [31] | 41 | 3 | 7.32% | 5.28% |

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | 133 | 8 | 6.02% | |||

| Poley 2012 [32] | 23 | 13 | 56.52% | |||

| Moon 2012 [33] | 21 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Park 2011 [34] | 43 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Hu 2011 [12] | 13 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Cholangitis | Sato 2020 [24] | 30 | 5 | 16.67% | 7.25% | |

| Poley 2020 [25] | 41 | 10 | 24.39% | |||

| Tringali 2019 [2] | 18 | 6 | 33.33% | |||

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | 118 | 18 | 15.25% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 32 | 4 | 12.50% | |||

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | 43 | 1 | 2.33% | |||

| Aepli 2017 [10] | 31 | 2 | 6.45% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 57 | 2 | 3.51% | |||

| Chaput 2016 [28] | 92 | 6 | 6.52% | |||

| Walter 2015 [29] | 38 | 5 | 13.16% | |||

| Saxena 2015 [3] | 123 | 5 | 4.07% | |||

| Hu 2014 [30] | 45 | 1 | 2.22% | |||

| Wagh 2013 [11] | 23 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Ryu 2013 [31] | 41 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | 133 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Poley 2012 [32] | 23 | 3 | 13.04% | |||

| Moon 2012 [33] | 21 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Park 2011 [34] | 43 | 2 | 4.65% | |||

| Hu 2011 [12] | 13 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Pancreatitis | Sato 2020 [24] | 30 | 1 | 3.33% | 4.04% | |

| Poley 2020 [25] | 41 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Tringali 2019 [26] | 18 | 1 | 5.56% | |||

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | 118 | 6 | 5.08% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 32 | 2 | 6.25% | |||

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | 43 | 1 | 2.33% | |||

| Aepli 2017 [10] | 31 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 57 | 3 | 5.26% | |||

| Chaput 2016 [28] | 92 | 5 | 5.43% | |||

| Walter 2015 [29] | 38 | 1 | 2.63% | |||

| Saxena 2015 [3] | 123 | 4 | 3.25% | |||

| Hu 2014 [30] | 45 | 1 | 2.22% | |||

| Wagh 2013 [11] | 23 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Ryu 2013 [31] | 41 | 4 | 9.76% | |||

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | 133 | 3 | 2.26% | |||

| Poley 2012 [32] | 23 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Moon 2012 [33] | 21 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| FCSEMSs | Pancreatitis | Park 2011 [34] | 43 | 6 | 13.95% | 4.04% |

| Hu 2011 [12] | 13 | 1 | 7.69% | |||

| Stent migration | Sato 2020 [24] | 30 | 1 | 3.33% | 14.51% | |

| Poley 2020 [25] | 41 | 24 | 58.54% | |||

| Tringali 2019 [26] | 18 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | 118 | 5 | 4.24% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 32 | 1 | 3.13% | |||

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | 43 | 2 | 4.65% | |||

| Aepli 2017 [10] | 31 | 1 | 3.23% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 57 | 16 | 28.07% | |||

| Chaput 2016 [28] | 92 | 23 | 25.00% | |||

| Walter 2015 [29] | 38 | 11 | 28.95% | |||

| Saxena 2015 [3] | 123 | 12 | 9.76% | |||

| Hu 2014 [30] | 45 | 3 | 6.67% | |||

| Wagh 2013 [11] | 23 | 9 | 39.13% | |||

| Ryu 2013 [31] | 41 | 6 | 14.63% | |||

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | 133 | 14 | 10.53% | |||

| Poley 2012 [32] | 23 | 1 | 4.35% | |||

| Moon 2012 [33] | 21 | 4 | 19.05% | |||

| Park 2011 [34] | 43 | 7 | 16.28% | |||

| Hu 2011 [12] | 13 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| MPSs | Abdominal pain | Costamagna 2020 [8] | 154 | 2 | 1.30% | 4.71% |

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | 10 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Canena 2014 [36] | 20 | 2 | 10.00% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 37 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 55 | 9 | 16.36% | |||

| Cholangitis | Costamagna 2020 [8] | 154 | 34 | 22.08% | 15.94% | |

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | 10 | 1 | 10.00% | |||

| Canena 2014 [36] | 20 | 1 | 5.00% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 37 | 7 | 18.92% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 55 | 1 | 1.82% | |||

| Pancreatitis | Costamagna 2020 [8] | 154 | 1 | 0.65% | 2.54% | |

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | 10 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Canena 2014 [36] | 20 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 37 | 3 | 8.11% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 55 | 3 | 5.45% | |||

| Stent migration | Costamagna 2020 [8] | 154 | 1 | 0.65% | 6.52% | |

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | 10 | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Canena 2014 [36] | 20 | 4 | 20.00% | |||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 37 | 3 | 8.11% | |||

| Cote 2016 [1] | 55 | 10 | 18.18% |

Table IV

Summary of rare adverse events

| Stent | Author | Patient (n) | Adverse event (n) | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDBSs | Basttistel 2020 [20] | 18 | Haemobilia (1) | 5.56 6.67 1.33 0.67 0.67 |

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | 150 | Haemobilia (10) | ||

| Abdominal wall haematoma (2) | ||||

| Intestinal loop laceration (1) | ||||

| Pleural effusion (1) | ||||

| Siiki 2018 [15] | 6 | Null | 0 | |

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | 10 | Liver abscess (1) | 10.00 3.74 15.89 6.54 | |

| Mauri 2016 [21] | 107 | Haemobilia (4) | ||

| Increased GGT/ALT (17) | ||||

| Biliary stone (7) | ||||

| Mauri 2015 [22] | 59 | Haemobilia (3) | 5.08 7.69 15.38 | |

| Giménez 2016 [23] | 13 | Haemobilia (1) | ||

| Elevated ALP (2) | ||||

| FCSEMSs | Sato 2020 [24] | 30 | Perforation (1) | 3.33 |

| Poley 2020 [25] | 41 | Cholestasis (1) | 2.44 2.44 2.44 | |

| Bleeding in bile duct (1) | ||||

| Elevated serum bilirubin (1) | ||||

| Tringali 2019 [26] | 18 | Null | 0 | |

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | 118 | Cholecystitis (3) | 2.54 4.24 2.54 9.32 | |

| Cholestasis (5) | ||||

| Cholelithiasis (3) | ||||

| Others (11) | ||||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 32 | Bleeding (1) | 3.13 6.25 | |

| Sludge obstruction (2) | ||||

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | 43 | Acute cholecystitis (1) | 2.33 11.63 2.33 | |

| Stent occlusion (5) | ||||

| Sludge obstruction (1) | ||||

| Aepli 2017 [10] | 31 | Null | 0 | |

| Cote 2016 [1] | 57 | Bile duct obstruction (1) | 1.75 1.75 3.51 15.79 | |

| Jaundice (1) | ||||

| Secondary bile duct changes (2) | ||||

| Others (9) | ||||

| Chaput 2016 [28] | 92 | Haemorrhage (1) | 1.09 1.09 1.09 4.35 | |

| Cholecystitis (1) | ||||

| Liver abscess (1) | ||||

| Biological abnormalities (4) | ||||

| FCSEMSs | Walter 2015 [29] | 38 | Flare up of chronic pancreatitis (1) | 2.63 2.63 2.63 2.63 5.26 2.63 |

| Cholecystitis (1) | ||||

| Portal vein thrombosis (1) | ||||

| Fever (1) | ||||

| Stent occlusion (2) | ||||

| Bleeding of duodenal varices (1) | ||||

| Saxena 2015 [3] | 123 | Stent occlusion (6) | 4.88 0.81 0.81 0.81 0.81 | |

| Tissue ingrowth (1) | ||||

| Stent fracture (1) | ||||

| Embedded stent (1) | ||||

| Stent-related death (1) | ||||

| Hu 2014 [30] | 45 | Null | 0 | |

| Wagh 2013 [11] | 23 | Bile duct stone (7) | 30.43 | |

| Ryu 2013 [31] | 41 | Stent occlusion (2) | 4.88 | |

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | 133 | Post-procedure pain (8) | 6.02 | |

| Stent occlusion (4) Bleeding (1) Unravelling of the stent (2) Hyperplastic reaction (1) | 3.01 0.75 1.50 0.75 | |||

| Poley 2012 [32] | 23 | Cholecystitis (1) | 4.35 8.70 4.76 9.30 7.69 7.69 7.69 | |

| Stent clogging (2) | ||||

| Moon 2012 [33] | 21 | Jaundice (1) | ||

| Park 2011 [34] | 43 | Sludge (4) | ||

| Hu 2011 [12] | 13 | Continuing pyrexia (1) | ||

| Abnormal liver function (1) | ||||

| Liver abscess (1) | ||||

| MPSs | Costamagna 2020 [8] | 154 | Post-endoscopic bleeding (5) | 3.25 0.65 5.84 3.25 |

| Ileal perforation (1) | ||||

| Bile duct stone (9) | ||||

| Jaundice (5) | ||||

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | 10 | Null | 0 | |

| Canena 2014 [36] | 20 | Stent clogging (2) | 10.00 | |

| Cote 2016 [1] | 55 | Bile duct obstruction (1) | 1.82 1.82 9.09 12.73 5.41 8.11 | |

| Jaundice (1) | ||||

| Secondary bile duct change (5) | ||||

| Others (7) | ||||

| Wu 2017 [6] | 37 | Post-sphincterotomy bleeding (2) | ||

| Sludge impaction (3) |

Abdominal pain

For abdominal pain, all 31 included studies reported this complication. After the meta-analysis in Figure 5, the lowest rate was found in the BDBS group (0.01, 95% CI: 0.00–0.07), although the differences among the groups were not significant. The pooled rate in the FCSEMS group was 0.03 (95% CI: 0.01–0.06), similar to that in the MPS group (0.03, 95% CI: 0.00–0.12). The heterogeneity result was high for all 3 groups (I2 = 69.39% and p < 0.001 for BDBSs, I2 = 78.47% and p < 0.001 for FCSEMSs, I2 = 78.44% and p < 0.001 for MPSs).

Cholangitis

For cholangitis, all 31 included studies reported this complication. After the meta-analysis in Figure 6, the lowest rate was found in the BDBS group (0.05, 95% CI: 0.00–0.20). The pooled rate in the FCSEMS group was 0.06 (95% CI: 0.03–0.10), lower than that in the MPS group (0.11, 95% CI: 0.02–0.23). The heterogeneity was high for all 3 groups (I2 = 92.01% and p < 0.001 for BDBSs, I2 =77.63% and p < 0.001 for FCSEMSs, and I2 = 79.74% and p < 0.001 for MPSs).

Stent migration

All 31 studies reported stent migration. After the meta-analysis in Figure 7, the lowest rate was found in the BDBS group (0.01, 95% CI: 0.00–0.02), although the differences among the groups were not significant. The pooled rate in the MPS group was 0.07 (95% CI: 0.00–0.20), which was lower than that in the FCSEMS group (0.12, 95% CI: 0.07–0.19). The heterogeneity was low for the BDBS group (I2 = 0.0% and p = 0.99) and high for the other 2 groups (I2 = 83.86% and p < 0.001 for FCSEMSs, I2 = 85.57% and p < 0.001 for MPSs)

Pancreatitis

All 31 included studies reported pancreatitis. After the meta-analysis in Figure 8, the lowest rate was found in the BDBS group (0.00, 95% CI: 0.00–0.01). The pooled rate in the MPS group was 0.02 (95% CI: 0.00–0.06), lower than that in the FCSEMS group (0.03, 95% CI: 0.02–0.05). The heterogeneity was low for all 3 groups (I2 = 35.57% and p = 0.16 for BDBSs, I2 = 13.57% and p = 0.29 for FCSEMSs, I2 = 48.72% and p = 0.10 for MPSs).

Technical success

All 31 included studies reported technical success. From the result of this meta-analysis, technical success was most likely to achieve when using BDBS (1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00). The pooled technical success rate of MPS was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.88–0.99), which was higher than that of FCSEMS (0.90, 95% CI: 0.85–0.94). The level of heterogeneity was low for the BDBS group (I2 = 0.00% and p = 0.62), and high for the other 2 groups (I2 = 76.72 % and p < 0.001 for FCSEMSs, I2 = 59.05% and p = 0.04 for MPSs) (Figure 9).

Treatment success

All 31 included studies reported treatment success. From the result of this meta-analysis, treatment success was most likely to be achieved when using BDBS (1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00). The pooled treatment success rate of MPSs was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.72–0.98), which was higher than that of FCSEMSs (0.82, 95% CI: 0.76–0.87). The level of heterogeneity was low for the BDBS group (I2 = 0.00% and p = 0.69) and high for the other 2 groups (I2 = 77.62% and p < 0.001 for FCSEMSs, I2 = 87.32% and p < 0.001 for MPSs) (Figure 10).

Stricture recurrent

All 31 included studies reported recurrent stricture. From the result of this meta-analysis, stricture recurrence was least likely to occur in the MPS group (0.07, 95% CI: 0.03–0.13). The pooled stricture recurrent rate of FCSEMSs was 0.11 (95% CI: 0.08–0.15), lower than that of BDBSs group (0.21, 95% CI: 0.16–0.26). The heterogeneity was evaluated as low for all 3 groups (I2 = 11.59% and p = 0.34 for BDBSs, I2 = 38.85% and p =0.05 for FCSEMSs, I2 = 39.30% and p = 0.16 for MPSs) (Figure 11).

Intervention frequency and recurrent time

In this meta-analysis, the cumulative need for intervention was reported in all 31 studies (Table V). For BDBSs, only 1 intervention of implantation was required to achieve clinical success, without the need for removal. For FCSEMSs, 1 implantation followed by 1 removal was required, as planned. However, for patients with persistent stricture during follow-up, ERCP was required 6 months after initial implantation, to replace FCSEMSs. Therefore, the cumulative need of intervention for FCSEMSs ranged from 2 to 3. Compared with the above 2 stents, the most obvious drawback of MPSs was the repeated needs of interventions. As reported in 5 of the included studies, its cumulate need of intervention ranged from 2 to 6. On the other hand, 21 of the included studies reported the duration from treatment success to stricture recurrent (Table V). BDBSs had the longest duration, at 16.1 months, and the duration for FCSEMSs was 7.0 months, longer than for MPSs (6.6 months).

Table V

Summary of intervention number and recurrence time

| Stent | Study | Intervention number (mean) n | Recurrent time (mean) [months] |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDBSs | Battistel 2020 [20] | 1 | NM |

| De Gregorio 2020 [19] | 1 | 27.8 | |

| Siiki 2018 [15] | 1 | 17.0 | |

| Dopazo 2018 [5] | 1 | 9.0 | |

| Mauri 2016 [21] | 1 | 15.4 | |

| Mauri 2015 [22] | 1 | 16.2 | |

| Giménez 2016 [23] | 1 | 11.0 | |

| FCSEMSs | Sato 2020 [24] | 2 | 19.5 |

| Poley 2020 [25] | 2 | 3.4 | |

| Tringali 2019 [26] | 2 | 7.9 | |

| Lakhtakia 2019 [9] | 2 | NM | |

| Wu 2017 [6] | 2 | 12.7# | |

| Schmidt 2017 [27] | 2 | NM | |

| Aepli 2017 [10] | 2 | 12.8 | |

| Cote 2016 [1] | 2.14 | NM | |

| Chaput 2016 [28] | 2 | 4.2 | |

| Walter 2015 [29] | 2 | 4.5# | |

| Saxena 2015 [3] | 2.2 | 4.0 | |

| Hu 2014 [30] | 2 | 3.0 | |

| Wagh 2013 [11] | 2.4 | NM | |

| Ryu 2013 [31] | 2 | NM | |

| Kahaleh 2013 [7] | 2 | NM | |

| Poley 2012 [32] | 2 | NM | |

| Moon 2012 [33] | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Park 2011 [34] | 2 | NM | |

| Hu 2011 [12] | 2 | 3.0 | |

| MPSs | Costamagna 2020 [8] | 4.2 | 1.5 |

| Ohyama 2017 [35] | 5.1 | – | |

| Canena 2014 [36] | 5.5# | 11.5 | |

| Wu 2017 [6] | 2# | 13.5# | |

| Cote 2016 [1] | 3.24 | NM |

Discussion

This meta-analysis was conducted to compare the therapeutic efficacy of 3 common stents (BDBSs, FCSEMSs, and MPSs) in endoscopic treatment of BBS, and the main goal was to draw a conclusion about which kind of stents should be recommended. According to the results of our study, BDBSs had the highest clinical success rate, which was associated with the easiest achievement of technical success. On the one hand, BDBSs were implanted in the biliary tract through a single intervention, without needing to consider the risk during stent removal [16, 21]. On the other hand, owing to the property of self-expansion, BDBSs could be initially loaded in a thin delivery catheter (6–15 F) and thus were able to pass through the tight stricture without any difficulties [16, 21]. The highest clinical success rate of BDBSs was also attributed to the relatively low migration rate. With the development of biodegradable materials (such as polydioxanone) for fabricating BDBSs, this kind of stent does not require a silicone covering on its surface, which was the main reason for the high migration rate of FCSEMSs. However, the stricture recurrence rate of BDBSs was the highest because of the uncontrolled degradation rate. BDBSs were mainly composed of amorphous regions of the matrix and crystalline area of the polymer, and the latter determined the mechanical and physical properties of these stents [16, 23]. The degradation of the crystalline area in vivo was influenced by many factors, so it was difficult to control the effective duration of these stents. As reported by Siiki et al., the stents in 1 patient were invisible at 3 months, but in another they were still in place at 6 months [15].

Comparisons between MPSs and FCSEMSs have been conducted in several previous studies. In a meta-analysis performed by Qin et al., they found that FCSEMSs had a lower clinical success rate than MPSs (OR = 0.48) [14]. However, the finding was opposite in another meta-analysis performed by Siiki et al. [39]. They showed that the clinical success rate of FCSMESs was higher than for MPSs (0.77 vs. 0.33). In our meta-analysis, the results demonstrated that MPSs had better clinical outcome than FCSEMSs (0.69 vs. 0.67). The reason for these contradicted results might be that each study aimed at a different range of patients with various causes of biliary stricture. Generally, MPSs tended to be applied in BBS caused by cholecystectomy, which had a good prognosis after endoscopic treatment. However, FCSEMSs were more often applied in BBS with poor prognosis, such as CP and LT [39, 40].

The total adverse event rates for these 3 stents were similar (0.31 for BDBSs, 0.40 for FCSEMSs, and 0.46 for MPSs), but the most common event related to each stent differed. For BDBSs, the most common adverse event was cholangitis. The reason is still unknown, but the reject reaction in the common bile duct caused by stent fragments after hydrolysis might be one of the factors [41]. Abdominal pain was the secondary common adverse event of BDBSs, owing to the forceful radial expansion of these stents. For FCSEMSs, stent migration was the most common adverse event. These metal stents were deliberately covered with silicone to make removal easy, but this also caused the stents to easily slip from the biliary tract [1, 30]. Like with BDBSs, cholangitis was another common adverse event of FCSMESs. FCSEMSs are usually designed with a larger diameter to a have longer patency period. However, this design also results in a reflux of duodenal contents, leading to cholangitis and sludge occlusion [42]. For MPSs, cholangitis resulting from frequent interventions was the most common adverse event.

To overcome the above limitations of these three stents, some newly designed stents and improved versions of current stents have emerged. For example, to prevent the reverse flow from duodenal lumen when using FCSMESs, an anti-reflux valve has been added at the duodenal end of these stents. As reported, this anti-reflux metal stent not only reduces the risk of ascending cholangitis during follow-up, but also prolongs the stent patency period [42]. To prevent the formation of biofilm on the inner surface of FCSEMSs, silver particles have been integrated in the silicone membrane. Because of the broad and effective antimicrobial activity of silver particles, the biofilm thicknesses on the surface of this stent was only 99.8 µm, which was dramatically reduced when compared with control group (122.9 µm). In addition, the inhibiting effect of silver particles also reduced the sludge impaction in this stent, leading to a longer patency period than conventional silicone-covered stents (179 vs. 116.5 days) [43]. Recently, a new kind of biodegradable stent, which behaves similarly to standard plastic stents, was designed with a helicoidal shape to deal with biliary stricture. The bile could flow through the double-spiral channel existing in the outer shell and centre core of this stent, which might reduce the possibility of stent obstruction. In addition, because this kind of biodegradable stent can be effectively implanted using common devices, there is no concern about readjustment of the position of the stent with special equipment [41].

To date, there have been many articles discussing which stent is more appropriate for malignant biliary stricture; however, few articles have been written about BBS. It is worth noting that the conclusions drawn about malignant biliary stricture were not applicable to BBS because of the significant differences in aetiology, prognosis, and survival time between these 2 conditions. Although a recent meta-analysis on BBS was published in 2020 by Almeida et al. [44], the authors only compared MPSs and BDBSs, not including FCSEMSs and the related articles from the last 2 years. On the other hand, they did not make necessary corrections in the statistical analysis of included data. For example, during the analysis of long-term stricture remission rates, the direct application of uncorrected data resulted in a 95% CI of more than 100% in 2 included papers, which was unreasonable. In the current meta-analysis, we used the statistical method of Freeman-Tukey transformation to correct the data because some of the incidences were close or equal to 100%. In addition, compared with previously published meta-analyses, the outcome measures in our study were more comprehensive, thus providing a reference to select an appropriate stent.

This single-arm meta-analysis had several limitations worthy of mention. First, because most included studies were case series reports, the experience of operator, endoscopic insertion device, stent implantation method, and definitions of outcome measures differed widely, which led to the pooled results lacking credibility. Second, because the meta-analysis included a large number of retrospective studies, some of the authors might be biased in reporting effective cases, which may have inflated the probability of technical success, treatment success, and clinical success. Third, the small number of included studies for the BDBS group and the MPS group rendered the pooled data unconvincing. Fourth, although some causes of BBS, such as CP and LT, were reported to have poor prognosis, we did not subgroup these aetiologies in the current meta-analysis, leading to the limited reference value of this study.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our meta-analysis provides a better understanding of the application of 3 common stents in BBS. Although prospective and controlled trials in this regard were unavailable and considerable heterogeneity was identified, this study demonstrated that the pooled clinical success rate of BDBSs was superior to those of FCSMESs and MPSs. The technical success, treatment success, and adverse event rate were also better in BDBSs than the other 2 stents, although their stricture recurrence tended to be more common. The conclusions drawn from this meta-analysis should be further confirmed by well-designed RCTs with large samples and long-term follow-up.