Introduction

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), associated with a shorter stay in the intensive care unit, shorter hospital stay, a better outcome, and lower costs, can be achieved through the introduction of multiple evidence-based perioperative measures that aim to diminish postoperative organ dysfunction. During recent years, overall compliance with ERAS protocols is associated with better outcomes in some surgical specialties, especially colorectal surgery.

Recently, the ERAS protocol for patients undergoing thoracic surgery has been published [1], but recommendations concerning patients undergoing cardiac surgery are still lacking. Key recommendations for the ERAS protocol for patients undergoing thoracic surgery include, among others, minimally invasive surgery, opioid-sparing anesthesia, ultrashort-acting anesthetics to facilitate early emergence and regional anesthesia to reduce postoperative opioid use. For patients undergoing thoracic surgery, regional anesthesia should be supplemented with a combination of acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) administered at regular time intervals, and dexamethasone may be administered to reduce pain and prevent post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

For cardiac surgery, this anesthetic protocol requires some modifications. Opioids play an important role in cardiac surgery, reducing myocardial cell injury caused by ischemia-reperfusion [2], and NSAID use is not recommended due to the risk of thromboembolic complications.

Thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA) and paravertebral block (PVB) are well-established methods for postoperative pain treatment, and both have previously been described as an analgesic option after thoracotomy [3]. The potential drawbacks of TEA include hypotension, epidural hematoma (1 : 5493, 95% CI: 1/970–1/31 [4]), and a significant risk of catheter misplacement (up to 12% of cases [5, 6]). The PVB is associated with a lower incidence of hemodynamic instability, nausea, and vomiting than TEA [7]. Pneumothorax is a typical complication of the procedure; however, the pleural puncture is less common when PVB is performed under ultrasound guidance [8].

Erector spinae-plane (ESP) block is a new loco-regional technique first described in 2016 [9] (Photo 1). A recent anatomical study by Adhikary et al. revealed that the distribution of the local anesthetic during ESP block is wider than that obtained with other regional blocks [10]. The feasibility and safety of the ESP block were shown in a variety of surgical procedures, including thoracic and cardiac surgery [11–13]. A potential advantage of the ESP block over PVB is the localization of the needle tip over the transverse process of the vertebra during deposition of a local anesthetic. For this reason, the risk of pneumothorax during ESP block is minimized.

Photo 1

The figure presents the needle position before (A) and after (B) injection of local anesthetic

NS – needle shaft, TM – trapezius muscle, RM – rhomboid major muscle, ES – erector spinae muscle, T4 – transverse process of the fourth thoracic vertebra. Small arrows indicate deposition of local anesthetic.

Aim

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the ESP block in patients subjected to mitral and/or tricuspid valve repair performed via right mini-thoracotomy.

Material and methods

Study design

This is an observational cohort study conducted in a tertiary cardiac surgery department. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee.

Participants

Informed, written consent was obtained from every patient. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who required mitral and/or tricuspid valve repair; (2) surgery performed using a right mini-thoracotomy approach; (3) participants older than 18 years; and (4) younger than 80 years.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) coagulopathy, defined as a known bleeding disorder; (2) allergy to local anesthetics; (3) depression, which could significantly influence pain perception; (4) epilepsy; (5) anti-depressant or epileptic drug treatment; (6) chronic usage of painkillers; (7) addiction to alcohol or recreational drugs.

Data from the patients who required endotracheal intubation and respiratory support for more than 2 h from the end of surgery were also excluded from the analysis.

Intervention

The ultrasound-guided single shot ESP block was performed before induction of general anesthesia. 0.2 ml/kg of 0.375% ropivacaine (Ropimol, Molteni, Italy) was administered at the level of the right transverse process of the fourth thoracic vertebra (T4), posterior to the erector spinae fascia (Photo 1).

General anaesthesia was induced using 0.2–0.4 mg/kg of etomidate (Hypnomidate, Janssen-Cilag International NV, Belgium), 0.4–0.6 μg/kg of remifentanil (Ultiva, GlaxoSmithKline, UK) and 0.6 mg/kg of rocuronium (Esmeron, N.V. Organon, The Netherlands) and maintained with sevoflurane 0.5 MAC (age-adjusted, Sevorane, Abbvie, USA) remifentanil infusion and incremental doses of rocuronium. Target-controlled infusion of remifentanil was started immediately after the bolus dose, and adjusted according to patient vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate) to a target plasma concentration of 4–8 ng/ml. The patient’s trachea was intubated with a double-lumen endotracheal tube. The right lung was deflated, the left lung was ventilated with air/O2, and normocapnia was maintained. When the surgery was completed, the residual neuromuscular block was reversed with sugammadex (Bridion N.V. Organon The Netherlands).

Approximately 30 min before the end of the surgery, patients received an intravenous bolus of oxycodone (0.1 mg/kg). Remifentanil infusion was decreased to the target plasma concentration of 0.5–2 ng/ml and continued for 60–120 min after the patient’s transfer to the intensive care unit. During this period, respiratory support was continued, and patients were observed for excessive postoperative bleeding and hemodynamic instability. Sixty to 120 min from the end of the surgery, remifentanil infusion was discontinued, and the patient’s trachea was extubated. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was started with a pump supplying incremental bolus doses of oxycodone (1 mg per bolus dose, lock-out time at 7-minute intervals, no basal infusion) during the first postoperative day. Standard postoperative pain management also included i.v. paracetamol, 1 g every 6 h.

Postoperative pain was evaluated by the nurses using a visual analog scale (VAS) at regular intervals. If a patient reported pain intensity exceeding 40 mm on the VAS scale, one or two supplementary doses of oxycodone (5 mg each i.v.) were administered by the nurse as rescue analgesia.

Patients were ambulated within the first 24 h post-operatively and transferred to the surgery ward by the end of the first postoperative day.

Control group – non-ERAS approach

Patients in the control group were managed differently. First, no regional analgesia was performed prior to the surgery. Second, the opioid used during the operation was fentanyl. Third, each patient was mechanically ventilated and sedated until the next day. Finally, postoperative pain was treated mainly with morphine, which was administered according to nurses’ discretion (a PCA pump was not used). Moreover, nurses evaluated pain intensity four times a day on the numerical rating scale (NRS) from 0 to 10, in which 0 means no pain at all, and 10 means the worst pain imaginable.

Outcomes

The main outcome measure was the total consumption of oxycodone during the first postoperative day. The secondary outcome was pain intensity assessed on the VAS at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after surgery by nurses. Another measured variable was patient satisfaction with pain management, assessed at the discharge from the hospital. Patients could describe their satisfaction with pain management as perfect (5), good (4), moderate (3), poor (2), or very poor (1).

Statistical analysis

Results obtained using the VAS are presented as means with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Student’s t-test was used for comparison of demographics between the ESP and control group. Nonparametric data were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test and presented as medians with interquartile range. Linear regression analysis was used to establish a relationship between continuous variables and the total use of oxycodone or pain intensity. All analyses were performed in Statistica 12.5 software (Stat Soft. Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

The study was conducted from February 7th to April 18th, 2018. Overall, we recruited 19 patients (10 women and 9 men) in the ESP group. Twenty-five individuals (11 women and 14 men) were analyzed in the control group. Patient demographics are presented in Table I.

Table I

Patient demographics

| Parameter | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 50.0 (43.0–57.0)* | 63.2 (58.0–68.4) |

| Weight [kg] | 73.8 (67.1–80.4) | 75.0 (69.3–80.7) |

| Height [m] | 1.70 (1.65–1.75) | 1.72 (1.67–1.76) |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 25.5 (23.4–27.7) | 25.4 (23.9–26.9) |

| Number of women (%) | 10 (52.6) | 11 (44.0) |

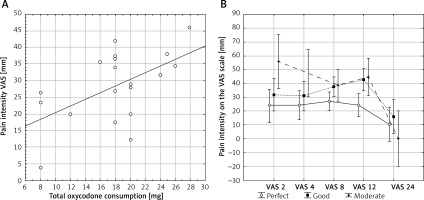

Pain intensity is presented in Figure 1.

The mean consumption of oxycodone in the ESP group during the first postoperative day was 18.26 (95% CI: 15.55–20.98) mg. A small difference in total oxycodone use was found between women (15.50 (1.17–19.83) mg) and men (20.89 (17.71–24.07) mg) (t = 2.24; p = 0.039), but after adjusting oxycodone use to patients’ weight, no statistically significant difference was found, although a slight tendency towards a lower consumption of opioid among women remained. Of 19 patients, only four required rescue doses of oxycodone.

Patient satisfaction

Of the 19 patients, 8 described pain treatment as perfect, 8 as good, and only 3 patients as moderate. None rated pain management as poor or very poor.

As expected, a positive correlation was observed between pain intensity and oxycodone consumption (r 2 = 0.30; p = 0.015, Figure 2 A). Patients who used more oxycodone reported more intense pain. Conversely, but as expected, patient satisfaction was negatively correlated with pain intensity measured on the VAS (F = 2.92, p = 0.008, Figure 2 B). More satisfied patients reported less pain.

Comparison of ESP group with standard care approach

Twenty-five in the control group were analyzed. A significant difference was found between the ESP and the control groups concerning patients’ age (Table I). Other demographic parameters were similar in both groups. No difference was presented in surgery time between ESP and control groups. The mean consumption of morphine in the control group was 12.64 (11.92–13.36) mg in the postoperative period. Pain intensity presented on the NRS was 3.72 (3.14–4.30), 3.56 (3.15–3.97), 3.12 (2.70–3.54), and 2.56 (2.22–2.90) for four subsequent measurements. Because pain severity was evaluated with different tools (VAS and NRS) and different time intervals, direct comparison of the two groups concerning pain intensity was not possible.

However, the main clinical finding was the mechanical ventilation time, which was significantly shorter in the ESP group (0.6 (0.4–1.1) h) than in the control one (10 (8–17) h, p = 0.00001). Moreover, patients in the ESP group spent fewer days in the intensive care unit (ICU) (1 (1–1)) than individuals in the control group (2 (2–2), p = 0.0001).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the ESP block was effective for pain management in patients undergoing mitral or tricuspid valve repair via right mini-thoracotomy. Our results on oxycodone consumption do not support previous reports regarding sex-related differences in oxycodone consumption [14, 15].

We attempted to perform the current study as a randomized controlled trial (RCT). However, as presented in Table II, severe respiratory complications occurred in the group without the ESP block. Given the data concerning difficulties with the postoperative pain control in patients who had remifentanil instead of fentanyl during the surgery, no regional analgesia, and oxycodone/paracetamol for postoperative pain relief, it seemed unethical to perform this study as an RCT, with no regional analgesia in the control group; therefore we decided to perform an observational trial.

Table II

Complications observed in a small patient group receiving standard care without the ESP block

We presented two different approaches to cardiac surgery, ERAS and standard care. In comparison to the ESP group, patients in the control group were ventilated for hours and spent several days in the ICU. We believe that early extubation of patients was possible due to the successful ESP block.

A significant and abrupt decrease in pain intensity 24 h postoperatively was associated with the removal of the chest drains. Prophylactic drainage of the thoracic cavity after cardiac surgery is a routine approach, as it provides the opportunity to observe postoperative bleeding, but it significantly increases pain intensity. None of our patients had clinically relevant bleeding, but all perceived more severe pain because of the presence of the drains, especially during coughing. Since anterior thoracic nerves (medial and lateral) innervate the upper region of the anterior chest wall, additional blockage of the areas covered by these branches of the brachial plexus may improve postoperative pain management [16–18]. Thus, we may speculate that the serratus anterior block or pectoral nerves II block may improve pain control in patients following mini-thoracotomy [18, 19].

A single-shot ESP block has a limited period of action as compared to continuous infusion of a local anesthetic. However, this type of cardiac surgery requires use of extracorporeal circulation with systemic heparinization, and leaving a catheter in such patients is controversial. Despite the aforementioned fact, some authors reported the possibility of continuous ESP analgesia in patients undergoing mitral valve repair via mini-thoracotomy [13].

Recently, new clinical trials have been published comparing the efficacy of ESP block and well-established analgesic techniques [20, 21]. According to results presented by Krishna et al., bilateral ESP block is more effective than conventional treatment with tramadol and paracetamol for postoperative pain relief in cardiac surgical patients [21].

Nagaraja et al. compared ESP with continuous TEA for postoperative pain management in cardiac surgical patients undergoing median sternotomy [20]. VAS score and pulmonary function were comparable in both study groups, but at some time points, pain severity was even lower after bilateral ESP than after TEA. Moreover, patients after ESP block could be extubated earlier than their counterparts in the conventional treatment group.

Evaluating the potential risk of the ESP block, we extrapolated the results from the continuous epidural or PVB analgesia, because of the limited information regarding ESP block itself. According to data presented by Landoni et al., the risk of epidural hematoma following continuous epidural analgesia in cardiac surgery is very low (1 per 3,552 operations) [22]. Moreover, epidural analgesia has been associated with a reduction in patient mortality, but the beneficial effect was rather low (number needed to treat (NNT) = 70). Other authors did not observe a higher risk of epidural hematoma in cardiac surgery patients than in general surgery patients [23, 24]. The risk of hematoma after PVB in cardiothoracic surgery seems to be even lower [25, 26]. According to these data, the potential risk of catheter placement seems to be extremely low.

Our study had some limitations, the most important of which is the lack of randomization. Moreover, the control group was treated differently. Thus, many aspects of perioperative care could not be compared between the groups. As shown by our previous experience, it may be very difficult or impossible to ensure patients’ comfort after mini-thoracotomy and open heart surgery without the use of regional analgesia, if fentanyl, which is routinely used for anesthesia, was replaced by ultrashort-acting remifentanil. Another limitation was the fact that our patients were observed for 1 day only. The small sample size is the next limitation of our study.

Conclusions

Nevertheless, our data suggest that the ESP block provides safe and efficient pain control in cardiothoracic surgery patients with the mini-thoracotomy approach, who have a high prevalence of severe postoperative pain, and may, therefore, have a role in the fast-track approach for these patients. This blockade seems to be simple and safe if performed under ultrasound guidance. The usefulness of ESP in other types of procedures needs to be studied more extensively.