Introduction

Have you ever felt a burning sensation in the centre of your chest? Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a very common chronic digestive disorder with a prevalence of approximately 18.1% to 27.8% in the United States [1]. GERD is primarily identified as a disorder of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES), which lies at the junction between the stomach and the oesophagus, which normally prevents the retrograde migration of gastric acid into the oesophagus [2]. The development of GERD has been mainly associated with impaired LES function due to impairment in the tone of the LES and transient relaxation of the sphincter [3]. The most common and classic symptom of GERD is heartburn. However, not all patients with GERD experience this symptom. Nonetheless, some patients also experience other symptoms like nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, difficulty or painful swallowing, and respiratory problems (like throat clearing and hoarseness of voice due to acid reflux into the larynx) [4, 5]. When left untreated, GERD can worsen and result in several serious complications, which include reflux oesophagitis, oesophageal strictures, Barrett’s oesophagus, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma [6]. GERD can also sometimes result in respiratory problems such as laryngitis and asthma [4].

Several risk factors have been identified and implicated in the pathogenesis of GERD; these include obesity, smoking, caffeine intake, anxiety, depression, pregnancy, hiatal hernia, and taking certain medications. Moreover, lifestyle and dietary changes have been advised for the management of GERD, these include smoking cessation, reduced intake of caffeine, spicy foods, citrus, and carbonated beverages, and avoiding heavy alcohol consumption, eating large meals in the evening, or high dietary fat intake [7]. Weight loss is highly recommended in overweight patients [8]. Elevation of the head end of the bed has also been shown to bring improvement in GERD symptoms [9].

We found the same research interest observed in Saudi Arabia and southern Indian medical schools. They proved that there is high probability of having symptoms of GERD among medical students because they are exposed to high levels of stress due to various factors such as having difficulty in coping with the curriculum and staying away from home and their families.

Also, they have some unhealthy eating habits like consuming the last meal right before bedtime, missing breakfast and eating fast. According to these studies, they found that students who have high body mass index (BMI) show GERD symptoms more frequent than others [10].

Aim

Basically, in this study, we show the extent of GERD in medical students in Jordan and how they deal with it, especially if there are modifiable lifestyle habits affecting the prognosis of the disorder.

Material and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among medical college students in Jordan during 2022 to assess the frequency of symptoms and to ascertain if there are specific risk factors for medical students.

Determination of sample size and sampling techniques

All students who attend the faculty of medicine and dentistry were included in the study. The study included 350 students, with a response rate of 75%. The students were selected from various universities and had different ages. The author distributed the questionnaire online to avoid face to face communication because of the COVID-19 pandemic and to ensure a wide spread among universities in different cities. This cross-sectional study did not give us cause-effects relationship; it concerns the prevalence of GERD and whether there were risk factors associated with it.

Inclusion criteria: Being between 18–24 years of age and an undergraduate medical student in Jordan.

Exclusion criteria: Students who have heart disease, malignant tumour, gastric surgery, hiatal hernia (> 3 cm) and gross oesophageal anatomic abnormalities

Date collection tools: A structured questionnaire was formulated by the authors after reviewing the literature, mainly consisted of the following parts:

Part (1): Socio-demographic variables: age, gender, academic year of study, college, university.

Part (2): Questions about GERD symptoms and how often they feel them. This included questions about heartburn (burning pain in the chest), nausea, vomiting, and regurgitation (feeling stomach contents moving upwards toward the throat or mouth).

Part (3): History of exposure to any risk factors and about their lifestyle, which included questions about smoking, alcohol consumption, caffeinated beverages, stressful life, eating large meals or certain foods that trigger the symptoms, and taking specific medications such as aspirin that can trigger the symptoms.

Part (4): Questions about what they do to relieve the symptoms, such as taking drugs, eating or drinking specific things, elevating the head, or changing postures, in addition to questions about things that exacerbate the symptoms from specific body posture to certain foods and drinks.

Part (5): Assessment of any other symptoms (complications), which included questions about dysphagia, hoarseness, coughing, sleep problems, and more.

Part (6): If they seek any professional medical help regarding the symptoms, with reasoning. An open-ended question.

Part (7): The effect of the symptoms on their life quality. An open-ended question.

Validity and reliability

The study tools were interpreted into Arabic, and the tools were presented to experts to assess their relevance and appropriateness.

Therefore, it was validated as the experts succeeded in retranslating the tools into English again without any changes in the meaning.

Reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) testing was done to examine the reliability, which was high and acceptable for scientific intentions.

Statistical analysis

The data were collected and statically analysed using the SPSS program (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Qualitative data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Counts and percentages were reported for all study parameters, as well as means and standard deviations.

Pearson’s χ2 test was used to represent the association of GERD with lifestyle changes in medical students; a bar chart was also used for a graphical summary of results. A post hoc analysis was performed to compare the scores across different levels, and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Trend charts also were reported to represent the behaviour of scores for different factors at different levels (Table I).

Table I

Descriptive statistics of the respondents

Results

A total of 350 participants were included in the study. 148 (42.3%) had experienced GERD symptoms in the past. Of these 148 students who had GERD, 99 (66.9%) were females and 49 (33.1%) were males. 202 (57.7%) had never experienced GERD symptoms, 67.7% of the results were from female students, while 32.3% were from male students. Most of the participants were aged between 18 and 24 years (94.3 %). Regarding the academic year of the respondents, it was distributed as follows: 17.4% were in their first year, 5.4% in their second year, 23.4% in their third year, and the fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-year students represented 19.7%, 21.4%, and 12.6% of the study sample, respectively (Table II).

Table II

GERD prevalence

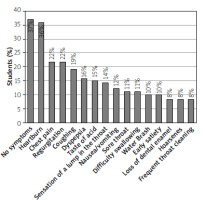

Figure 1 summarises GERD symptom prevalence. Most of participants were asymptomatic (37%), while in symptomatic participants the most common symptom was heartburn (36%) followed by chest pain and regurgitation (22% each). The next most commonly reported symptom was coughing (19%), followed by dyspepsia (16%), and taste of acid (15%). Some symptoms were also reported, including the sensation of a lump in the throat (14%), nausea and vomiting (12%), sore throat (11%), and water brash and early satiety (10%).

The study found that eating spicy food significantly increases the probability of having GERD symptoms in GERD patients and GERD-free participants (50.7% and 20.8%, respectively). Drinking milk was statistically proven to relieve the symptoms of GERD (38.5%), as illustrated in Table III.

Table III

Common symptom scores and association with GERD

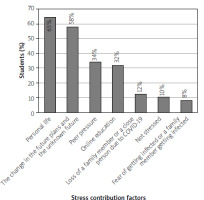

Stress was found to have a significant impact on GERD symptoms, as 60.1% of students who subjected to stress had GERD, as illustrated in Table IV. Personal life stress was found to be the main cause of stress (65%), and only 10% of the students were not stressed, while the change in future plans and an unknown future caused stress to 58% of the students. Peer pressure, online education, and the loss of a family member due to COVID-19 stressed 34%, 32%, and 12% of the students, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Table IV

Food item intake associated with GERD

Table V shows that none of the medical risk factors (i.e. previous endoscopy, hiatal hernia, decreased oesophageal motility, reflux esophagitis, and asthma) had any statistical association with GERD in the participants. However, 13% of the students took NSAIDS, but there was no statistical evidence of any association with GERD-diagnosed students.

Table V

Lifestyle conditions associated with GERD

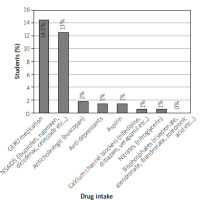

Table V shows that 42 (28.4%) participants who had been diagnosed with GERD took GERD medications.

Discussion

GERD is one of the chronic illnesses of the digestive system that is common in adult age group. A systematic review demonstrated that the prevalence of GERD ranged from 8.7% to 33.1% in the Middle East [11]. In our study we are concerned about the prevalence of GERD symptoms and the most presented symptoms of GERD among medical students in Jordan. In addition, many factors may contribute to the development of GERD, and some of these risk factors were studied as non-preventable factors, such as age, sex, or genetics and preventable factors, such as lifestyle and dietary habits, and excessive body weight [7], so in our study we were concerned about the risk factors that are known to increase GERD symptoms and study the correlations between them, in addition to the impact of GERD symptoms on quality of sleep and the lifestyle habits of medical students.

In line with this hypothesis, the study detected that the prevalence of GERD symptoms among medical students in Jordan is 42.3%. Students who complained mainly of heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain reported that these symptoms were increased with a correlation to psychological stress, which is the most common risk factor that causes GERD among medical students. 60.1% of GERD patients suffer from psychological stress, and they recorded an average of 7.05/10 on a stress scale, and this average is considered relatively high. This can be due to the fact that psychological stress is more common in medical students [12]. Students experience high stress levels in their final educational years [13].

Figure 3 shows that 65% of students were mainly stressed because of their personal life, pressure of studying and a lot of examinations, peer pressure, online education, and the loss of a family member due to COVID-19. 58% of students were concerned about future planning and the methods of learning. To a lesser degree they also feared about being infected or diseased.

The diagnosis of GERD in undergraduates was considered by the frequency and severity of GERD symptoms (such as heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, and upper stomach pain that radiates retrosternally) and their impact on students’ life quality. The study found that 37% of undergraduate did not have any GERD symptoms, and the rest (63%) had GERD symptoms, and the most presented symptoms were heartburn (36%), chest discomfort and regurgitation (22% for each). In addition to that, 19% had cough, 16% dyspepsia (indigestion), and 15% a taste of acid. The least recorded symptoms were a sensation of a lump in the throat, nausea and vomiting, water brash, early satiety, sore throat, hoarsens of voice, and dysphagia.

The data also suggest that there is a correlation between GERD symptoms and some risk factors; one of them is bad dietary habits such as sleeping immediately after meals, and eating chocolate, spicy, fatty, and fried food; these habits were clearly associated with making reflux symptoms worse and more frequent, especially spicy food, which increased GERD symptoms with by 33.8%. The data also reported that 28.1% of students drank milk and changed position (sitting upright) to relieve GERD symptoms. However, an exploratory analysis suggests that increasing the consumption of either low-fat or full-fat dairy foods to at least 3 servings per day does not affect common symptoms of GERD compared to a diet limited in dairy [14].

Additionally, the data suggest that modification of some lifestyle habits helped medical students to alleviate reflux symptoms; these modifications include avoiding heavy meals, especially at nighttime, and reducing intake of spicy food, chocolate, coffee, and tea. They started to be more careful about the quantity and quality of food, trying to avoid symptoms.

Some studies have shown that there was an improvement in GERD symptoms when drinking decaffeinated coffee [15], and this is in line with what some students believe, i.e. that reducing caffeine intake helps in mitigating symptoms of the disease.

Our study did not find a direct correlation between GERD symptom prevalence and smoking, alcohol intake, or high BMI. This may be because of the small numbers of students who smoke (14.2%) and 13.4% who have high BMI, and only 0.6% drank alcohol. Also, the study detected that there is no correlation of GERD and students’ gender or their academic year.

Table VI shows that other risk factors that we asked about were students’ past medical or surgical history, such as if they had undergone a previous gastrointestinal endoscopic procedure, or if they had been diagnosed with hiatal hernia or decreased oesophageal motility; these risk factors presented in 8.8% of medical students, but none of these risk factors (i.e. previous endoscopy, hiatal hernias, decreased oesophageal motility, reflux esophagitis, and asthma) showed any statistical association with GERD. Those who visited a gastroenterologist stated that the most common symptoms they had were heartburn, dyspepsia, chest discomfort, and for a short time nausea, vomiting and salivation.

Table VI

Medical history associated with GERD

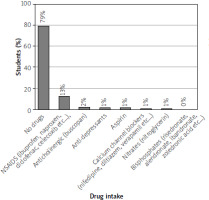

Figure 4 which illustrates drug intake frequency shows that 14.5% of medical students took medications for GERD, but not regularly (only when symptoms worsened or when they had exams or after heavy meals). Some of the medications they used were antacids, H2 antagonists, and PPIs, which were helpful in subsiding their symptoms.

The data suggest that most students were generally healthy and were not diagnosed with chronic illnesses, except for a small percentage (4.8%) who were diagnosed with asthma.

Reflux oesophagitis and oesophageal strictures are benign complications of GERD; however, it can be complicated to premalignant or malignant lesions such as barrettes oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Laryngitis is also one of the extra-gastrointestinal complications that can develop in GERD patients [16]. The analysis of our study found that 10.6% of GERD patients had one of these complications, and the most common was reflux oesophagitis with a percentage of 7.1%. These findings are in line with a study that was done to identify the complications of GERD [17]. Some students took NSAIDs, which are suggested to increase the symptoms of GERD [18], but our study did not find a direct correlation between GERD and NSAIDs.

The study provides new insight into the relationship between GERD symptoms and sleep problems; it was reported in a previous study that GERD is strongly associated with many sleep disturbances [19] and with impairment in objective sleep quality [20]. In our study, we found that 39.8% of students reported that they had changes in sleep patterns associated with GERD symptoms.

Conclusions

GERD symptoms are frequently encountered among the population, with an increased prevalence in medical students. The most common symptom in our study was heartburn. However, most of the students were asymptomatic. Multiple potential risk factors have been identified including psychological stress and bad dietary habits.