Introduction

Cachexia and malnourishment are common events during treatment of cancer patients. Overall one third of patients with malignancy suffer from cancer cachexia, this proportion being notably higher among patients affected by solid cancers, with a prevalence of 60–80% in advanced cancers [1–4].

Cancer cachexia severely jeopardizes patients’ quality of life and performance, and substantially contributes to morbidity and mortality of treatable cancers. It is an independent predictor of shorter survival and it increases the risk of treatment failure, and toxicity. It was estimated that cancer cachexia may directly contribute to 30% of cancer deaths [3–6].

However, in spite of its frequency and its severe negative impact on patients’ performance and clinical outcomes, cancer cachexia screening, assessment and treatment are frequently less than satisfactory in daily oncology practice [2, 7, 8]. Medical oncologists and other healthcare oncology professionals treating patients with cancer seem indeed to neglect patients’ nutritional issues, any setting considered [8–10]. This was one of the main factors that led the European Cancer Patient Coalition to publish a Cancer Patient’s Nutritional Bill of Rights, which was presented in the European Parliament in Brussels in November 2017 [11].

A crucial question to answer is why this low level of priority in cancer cachexia management exists in daily clinical practice.

Considering that clinical practice guidelines are important for translating evidence into medical decision making and clinical practice applications, reducing undesirable practices and encouraging services of proven efficacy [12], we hypothesized that one of the possible causes of current medical mismanagement of cachectic patients might stem from a low level of cancer-cachexia guideline recommendations among oncology educational and policymaker societies/institutions at a global level [13]. Indeed, medical recommendations’ delivery in websites has been documented to be of extreme importance, since it improves patient safety, reduces complications and shortens length of stay among Medicare beneficiaries [14].

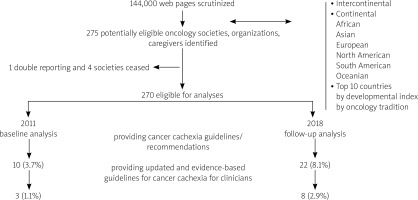

In 2011 we launched a Web-based study with the aim of examining the global intercontinental coverage and consistency of Web guidelines for cancer cachexia produced by oncology related professional societies and their changes over time [13]. In our first analyses (June 2011) data from 275 oncology societies/health providers were scrutinized. The magnitude of “updated” and “evidence-based” cancer cachexia guideline recommendations on the Web among oncology societies was found to be extremely low at a global level irrespectively of continent, nation, developmental index, and type of oncology providers scrutinized [13]. We therefore concluded that the low level of global Web recommendations could be one cause of the observed low rank of priority given to the management of cancer cachexia in daily oncology practice.

Overall the number of guideline recommendations on the net from medical societies (any setting considered), and the use of internet and medical websites from physicians had an exponential growth in the last decade, giving a comprehensive picture of flourishing medical activities and scientific progress. But what happened with cancer cachexia?

We here report the June 2018 update of our study. Both magnitude of global Web recommendations for cancer cachexia for physicians among oncology related societies and their trend to change overtime (2011 vs. 2018) are analyzed.

Material and methods

Identification of pertinent societies and caregivers

In 2011, 144,000 Web pages were scrutinized during internet searches in order to identify oncology societies/organizations that might have provided Web guidelines regarding cancer cachexia [13] (Appendix 1). We considered societies and organizations that were intercontinental (with a global outlook), continental (including two or more countries in the same continent: African, Asian, European, Oceanian, North American, South American), or national belonging to one of the top 10 countries with the highest development index (Norway, Australia, New Zealand, USA, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Netherlands, Canada, Sweden, Germany) [15]. Countries with a long lasting tradition in medical oncology but not included in the top 10 highly developed countries (Austria, Belgium, China, Denmark, France, Japan, Italy, UK, Spain, Switzerland) were further included in the internet searches (Table 1). Due to notable economic and development differences between South and North American countries, the continental entities were separately analyzed for North and South America.

Table 1

Demographics of the scrutinized societies and caregiver organizations

| Demographics | All n = 275 | Eligible n = 270 | 2011 any recomm. cachexia n = 10 | 2018 any recomm. cachexia n = 22 | 2011 EBU guidelines cachexia n = 3 | 2018 EBU guidelines cachexia n = 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continent | ||||||

| Intercontinental | 26 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| North America | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| South America | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Europe | 24 | 24 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Africa | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asia | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oceania | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Top 10 developed countries* | ||||||

| Norway | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Australia | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Zealand | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| USA | 46 | 45 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Ireland | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liechtenstein | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada | 16 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sweden | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Germany | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other countries | ||||||

| Japan | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 13 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Italy | 9 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Switzerland | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spain | 10 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Belgium | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Denmark | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| France | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| China | 12 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Austria | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nations by economic-geographic area | ||||||

| Australia – New Zealand | 18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Benelux | 14 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Germanophone | 27 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| North America | 62 | 61 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 4 |

| Scandinavian | 10 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South European | 28 | 28 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| UK-Ireland | 22 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| East Asian | 23 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Society type | ||||||

| Cancer research | 52 | 52 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Radiation oncology | 34 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medical oncology | 25 | 25 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Surgical oncology | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Supportive care | 10 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Comp. cancer manag. | 71 | 71 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| Other | 63 | 63 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

* Countries were selected from the top 10 countries according to the human development index available in 2011

Comp. cancer manag. – comprehensive cancer management; economo-geographic area: Australia-New Zealand vs. Benelux (Belgium and Netherland) vs. German speaking countries (Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, Switzerland) vs. North American (US and Canada) vs. Scandinavian (Denmark, Norway and Sweden) vs. South European (France, Italy and Spain) vs. United Kingdom vs. East Asian (Japan and China)

Since guideline release may be influenced by each nation’s economics and traditions, the national guidelines retrieved were further shared in groups by economic-geographic area: Australia-New Zealand vs. Benelux (Belgium and Netherland) vs. German speaking countries (Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, Switzerland) vs. North American (US and Canada) vs. Scandinavian (Denmark, Norway and Sweden) vs. South European (France, Italy and Spain) vs. United Kingdom vs. East Asian (Japan and China).

We further constructed a database of 275 oncology related educational and policymaker societies, caregivers, and organizations that might provide guidelines for cachexia in cancer patients [13]. Of these, 4 ceased and one was the Spanish duplicate of NCI, leaving 270 oncology societies/policymakers eligible for comparative analyses between 2011 and 2018 (Appendix 2). Relative websites were thereafter scrutinized for cancer cachexia/malnutrition guideline recommendations both in June 2011 and in June 2018 (Fig. 1).

Analyses were performed in ITT fashion; thereafter all the 270 eligible societies were scrutinized independently of the Web page accessibility (having no functional Web page, having Web page under construction, having no webpage, having no e-link active) at the time of analyses (June 2011 and June 2018).

Primary outcome

To scrutinize the global magnitude of “updated” and “evidence-based” guideline recommendations for cancer cachexia for physicians on the Web and its changes over time. We considered as “updated” all the Web guidelines that have been produced or revised or lastly adjourned within the last five years. Evidence-based guidelines were considered to be all those including randomized controlled trials and/or meta-analyses in references to support sentences.

Secondary outcome

To depict the global attitude towards cancer cachexia Web recommendations/guidelines (any level of evidence, any target).

Since all medical societies may not have the possibility to produce “internal” guidelines (“own” guidelines), we considered of value both “own” produced guidelines and/or those provided as a “link” to a specific website of another society with recommendations for cancer cachexia.

Results

Eligible societies and organizations

Overall 275 oncology-related educational and policymaker societies were registered in 2011 [13], and 270 of these were eligible for comparative analyses and were scrutinized for cancer cachexia guideline recommendations both in June 2011 and in June 2018 (Appendix 2).

Among these, 67 were international (23 intercontinental and 44 continental: African, American, Asian, European, Oceania), 109 belonged to the top 10 countries with the highest development index available in 2011 [15] and 94 pertained to countries with a long lasting tradition in medical oncology but not included in the top 10 highly developed countries. Searches for North America did not lead to comprehensive (US + Canada) North American societies/organizations and only societies for each separate country were retrieved and scrutinized. The retrieved and analyzed oncology societies and organizations covered a large array of oncology settings (educational/clinical/research/policymaker): most societies were devoted to comprehensive cancer management (n = 71), cancer research (n = 52), radiation oncology (n = 34) and medical oncology (n = 25), while only a minority pertained to surgical oncology (n = 15) and supportive oncology (n = 10) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Coverage of Web global recommendations on cancer cachexia

Despite the extensive search and the notable number of societies organization eligible for analyses (n = 270), we found only 10 societies/organizations giving cachexia recommendations in 2011 [16–25] and only 22 societies in 2018 [26–47]. Thus, since the paucity of events may have led to unreliability of statistical comparison within categories, descriptive statistics were adopted when χ2 and Yates’ χ2 tests were not applicable.

Overall Web recommendations provision

We found a statistically significant increase (χ2 p = 0.0287) in the proportion of oncology societies/organizations providing recommendations for cachexia between 2011 and 2018 (3.7% vs. 8.1%) [16–47].

Primary outcome

When only updated and evidence-based guidelines were analyzed (guidelines updated within five years and with references including randomized controlled trials and/or meta-analyses to support sentences), we found that the proportion of oncology societies implementing cancer cachexia guidelines for physicians was almost nil both in 2011 and 2018 (1.1% vs. 2.96%) (Table 1). Indeed, only three [17, 20, 21] and eight [28, 32, 33, 35, 38, 39, 45, 47] societies provided level one evidence-based and updated cancer-cachexia guideline for physicians in 2011 and 2018 respectively (χ2 p = 0.1277, Yates’ χ2 p = 0.2229). Nonetheless, consistency of these recommendations notably varies among scrutinized providers: from some paragraphs in the framework of supportive care guidelines [33], to extended and detailed guidelines [35, 38, 39, 45].

Evidence-based and updated guidelines for both cancer cachexia assessment and management were provided by two societies in 2011 [20, 21] and by seven societies in 2018 [28, 32, 35, 38, 39, 45, 47] while one organization produced recommendations mainly for cancer cachexia management [17, 33].

Almost all societies produced their own guidelines/recommendations either in 2011 and in 2018 [17, 20, 28, 32, 33, 35, 45, 47], while one organization in 2011 [21] and two societies in 2018 were presenting cancer cachexia guideline/recommendations by link to guidelines produced by other societies [38] or a consensus panel [39].

Web guideline provision by geographic areas

International societies

No recommendations were found among the scrutinized Asian, African Oceanian, and South American societies. Most cancer cachexia Web recommendations/guidelines were provided by European oncology societies [20, 21, 27–31]. However, even the overall European guideline provision was notably low (Table 1). Thus, the comprehensive international guideline release was inconsistent and not influenced by the continent analyzed (intercontinental vs. African vs. Asian vs. European vs. Oceanian vs. South American) both for primary and secondary outcome, both in 2011 and 2018 (Table 1).

National societies

The level of cancer cachexia recommendations and guidelines was almost zero across the different national oncology societies scrutinized either in 2011 and 2018. Paucity of evidence-based guidelines and/or overall cachexia recommendations was independent of the high developmental index of the nation and the oncology tradition. Most of the national guidelines were produced by Chinese [46, 47], Italian [25, 44, 45], Spanish [39, 40], and US societies [16–18, 32–37]. Societies from most nations analyzed do not provide any evidence-based and updated guideline either in 2011 or 2018 (Table 1).

When national guidelines were analyzed by economic-geographic area, we found that guideline production was higher among countries from North American and Southern European economic-geographic areas, but the observed differences were not statistically significant (Table 1).

Web guidelines provision by society type

Analyses for society type did not translate into any recommendation difference at any time point (2011 vs. 2018) either for overall recommendations for cancer cachexia (2011 Yates’ χ2 p = 0.54 ; 2018 Yates’ χ2 p = 0.29) or for evidence-based and updated cachexia guidelines for physicians (2018 Yates’ χ2 p = 0.065, 2011 almost null recommendation and statistics not applicable) (Table 1).

However, a major change should be underscored both for major societies for comprehensive cancer management and for major medical oncology societies. In 2011 no guidelines at any level were retrieved from medical oncology, radiation oncology or surgical oncology societies/organizations. In 2015 ASCO (the American Society of Clinical Oncology) included a chapter for the management and assessment of cancer cachexia in its educational book [32]. ESMO (the European Society of Medical Oncology), at the time of data extraction in 2018, was producing its official guidelines, and in its website has a ppt module for cachexia e-learning (last adjourned in 2017) [27]. All major societies involved in comprehensive cancer management, NCI, NCCN, ESO provided their own evidence-based and updated guideline in 2018 [28, 33, 35]. Surprisingly, still in 2018, surgical oncology and radiation oncology societies do not provide any guideline for cancer cachexia (Table 1).

Discussion

An impressive number of cancer societies, cancer organizations and oncology policymakers have been developed over time, offering a general picture of flourishing professional and scientific activity.

We scrutinized 270 cancer societies/organizations that operate at the international or national level either in 2011 and 2018. Among these, we found that the provision of Web guideline recommendations for cancer cachexia for physicians was extremely poor at any time point analyzed. Paucity of Web guideline recommendation was found to be a global phenomenon and it was independent of the continent analyzed (Africa, America, Asia, Europe, Oceania), nation analyzed, high developmental index of the nation analyzed, oncological tradition of the country, and national grouping by economic-geographic area (Australia-New Zealand vs. Benelux vs. German speaking countries vs. North American vs. Scandinavian vs. Southern European vs. United Kingdom vs. East Asian).

Overall, ten (3.7%) of the scrutinized societies were providing some form of recommendations in 2011 and twenty-two (8.1%) in 2018. Nonetheless, consistency of provided guidelines was disappointingly scant. Only three societies (1.1%) in 2011 and 8 societies (2.96%) in 2018 were providing updated and evidence-based guideline for physicians for the assessment and management of cancer cachexia. Guideline consistency by both evidence provision and continual updating is not a redundant issue. Evidence-based recommendations reduce undesirable practices and encourage services of proven efficacy [12, 14]. In turn, timelines of guideline updates is crucial, since the implementation of outdated guidelines in clinical practice may lead to a lack of updated clinical decisions and practices.

Thus we found that the global provision of Web guidelines for cancer cachexia was extremely inadequate both for coverage and consistency.

A crucial question to answer is why this low level of priority in provision of guideline recommendation for cancer cachexia exists.

Cancer cachexia is a common event during treatment of cancer patients. It may reach prevalence of 60–80% in advanced cancers [1–4], with severe implications for quality of life, occupational possibilities and treatment outcomes, directly contributing to 30% of cancer deaths [3–6, 48].

Nonetheless, medical oncologists and other healthcare professionals treating patients with cancer seem to neglect patients’ nutritional issues [8–10, 48]. This should not surprise and underscores an astonishing European report for cancer pain management where half of the patients believed that their quality of life was not considered a priority in their overall care by their health care professionals [49].

Does the reported paucity of guidelines explain the level of awareness of cancer cachexia in daily clinical practice? Probably yes, it may constitute a cause, since medical recommendations’ delivery in websites has been documented to be of extreme importance in enhancing the implementation of practices of proved evidence in daily clinical activities [14].

Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? In 2011 no guidelines at any level were retrieved from strict medical oncology, radiation oncology or surgical oncology societies/organizations. In 2018 still no investigated surgical oncology societies (including ESSO, SSO) and radiation oncology societies (including ESTRO, ASTRO) provided any guideline for cancer cachexia. However, in the face of the general discouraging global scarcity in guideline provision, we found that both major societies for comprehensive cancer management and major medical oncology societies (ASCO, ESMO, NCCN, NCI, ESO) were providing or were going to provide evidence-based recommendations on their websites. This last finding may be of extraordinary importance and may constitute a cornerstone for better management of cachexia and nutritional derangements in the near future. Indeed, all of these organizations have very extensive membership, organize large meetings and have a substantial influence upon their members, subscribers, and visitors to the websites. Nonetheless, the overall global provision of guidelines continues to be very scant.

We have to discuss some limitations of our study. Firstly, since there are no established validated searches for unearthing professional societies and organizations, some of them may have been missed by our searches. However, given the multiple layers of our search, and the large number or oncology societies retrieved, it is unlikely that prominent oncologic entities were missed and that missed societies may change the global patterns of Web guideline provision for cancer cachexia [13, 50–52]. Secondly, our searches were oncology oriented, and thus some nutritional (non-oncology) societies with nutritional guidelines such as ESPEN (European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) have been lost by our searches. However, it is unlikely that medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and surgical oncologists (the physician gatekeeper for the oncology patients) will routinely visit nutritional societies’ websites in their daily practice to take care of their patients. Thus, for nutritional societies, we consider as a “guideline-presence event” only a Web link to these guidelines from the scrutinized 270 societies. Finally, the human development index (HDI) changes over time. Thus, in June 2018 (at the time of data extraction) [53], countries’ position variations as compared to the top 10 available in June 2011 were reviewed [15, 53]. Among the 188 nations analyzed by the HDI, seven countries included in the top 10 for HDI at time of our analyses in 2011 (Norway, Australia, USA, Ireland, Netherland, Canada, Germany) [15] continued to be in the top 10 at the time of our data extraction in June 2018 [53]. The remaining three countries continue to rank at the top of the list, all included in the top 15 positions (New Zealand 13/188, Sweden 14/188, and Liechtenstein 15/188) [53]. Therefore, no significant biases may be attributed to the country with the highest developmental national index migration at the two time-points of analyses.

Conclusions

Cancer cachexia global awareness among oncology societies seems to be extremely low since related level guidelines implementation was found to be inconsistent both for coverage and consistency at any level and time-point analyzed (nation vs. continent vs. international vs. economic-geographic area vs. oncology society type vs. 2011 and 2018). Some lights of hope seem to appear at the end of the tunnel since some major oncology societies have provided or are still developing some guidelines or educational material for the management of cancer cachexia on their websites. A lot of work has to be done in guidelines provision for cancer cachexia, in order to improve clinical management of cachectic patients in daily oncology practice.