Introduction

Melanomas are widely recognized for their diverse morphological features, which can resemble various other types of tumours, posing a challenge for surgical pathologists in both primary cutaneous and metastatic sites [1, 2]. Uncommon variations of melanoma may exhibit distinct cytological characteristics such as balloon cells, signet-ring cells, rhabdoid cells, clear cells, giant cells, or small round cells. Additionally, they may display unique histomorphological traits including myxoid change, osteosarcomatous differentiation, and pseudoglandular or angiomatoid change. The occurrence of ganglioneuroblastic differentiation in melanocytic lesions is exceedingly rare, with only a few documented cases in the literature [1]. Histologically, this phenomenon is characterized by the presence of ganglion-like cells, exhibiting abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm with Nissl substance, well-defined cell boundaries, enlarged and eccentric nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and a neuropil background.

Melanoma of unknown primary (MUP) is a rare phenomenon with an incidence ranging from 1 to 8% and an elusive aetiology [3]. Typically, MUP emerges in lymph nodes, although it can also manifest in subcutaneous tissue and visceral organs. Depending on the location of initially diagnosed lesion, MUP is classified by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as stage III or IV [4]. Compared to melanoma with a known primary at the same stage, MUP has favourable survival rates and should be considered for aggressive radical therapy [3]. Melanoma of unknown primary presenting with unusual histopathological features may be easily misdiagnosed, leading to inadequate treatment.

This case study provides insights into the histopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of an occult melanoma displaying ganglioneuroblastic differentiation.

Case report

A 76-year-old male with hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, coronary artery disease, benign prostate hyperplasia, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation presented an axillary lymphadenopathy observed for 2 years. He had previously undergone an excision of haemangioma of the chest one month prior and removal of the nail due to subungual lesion. For the latter no histopathological specimen or report was available for consultation, but according to the patient the lesion was nonneoplastic. An excisional biopsy of the enlarged left axillary lymph node measuring up to 10 cm was performed.

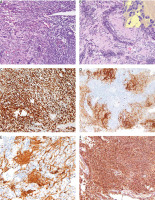

Microscopic examination revealed a biphasic neoplasm comprising a spindle cell component and ganglioneuroblastic elements, forming neuropil-like areas (Fig. 1). The ganglioneuroblast-like cells had plump cytoplasm and displayed eccentrically located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The microscopic presentation was equivocal, so extensive immunophenotyping was performed (Table 1). The spindle cells demonstrated positive immunostaining for SOX10 but were negative for classic melanoma markers HMB45 and melan-A. Moderate to strong expression of PRAME was observed in the majority of cells. The ganglioneuroblastic elements exhibited positive staining for synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and neurofilaments. The proliferation index Ki67 was estimated to be 55% globally and tended to be slightly higher in the spindle cell component. Neurofilament staining was particularly pronounced in areas of neuropil. The final histopathological diagnosis, based on morphology and immunophenotype, was determined to be melanoma with ganglioneuroblastic differentiation. Macrodissected tumour tissue from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue block was tested for mutations in BRAF exons 11 and 15 and NRAS exons 2, 3, 4 (BRAF/NRAS Mutation Test, version 04, Roche; Roche Light Cycler 480 SW v 2.0.0), that revealed a p.(Gln61Xaa) mutation in NRAS exon 3.

Fig. 1

The neoplasm exhibited a biphasic appearance with spindled and ganglioneuroblastoma-like cells (A), neuropil formation was observed within the tumour. The inset in panel B highlights the presence of ganglioneuroblastic differentiation at high magnification (B), immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of SOX10 (C), synaptophysin (D), neurofilaments in the neuropil areas (E), and diffuse PRAME (F)

Table 1

Immunophenotype of spindle cell and ganglioneuroblastic components of melanoma in the current case

| Marker | Spindle cell component | Ganglioneuroblastic component |

|---|---|---|

| SOX10 | + | – |

| SOX11 | – | – |

| Melan A | – | – |

| HMB45 | – | – |

| PRAME | +/– | – |

| NSE | – | + |

| NFP | – | + |

| S100 | – | + |

| CK AE1/AE3 | – | – |

| H3K27me3 | + | + |

| Desmin | – | – |

| MyoD1 | – | – |

| INI1 | + | + |

| Synaptophysin | –/+ | + |

| BRAF V600E | – | – |

A thorough dermatological examination did not reveal any primary lesion. Subsequent positron emission tomography scanning did not show any foci of enhanced glucose uptake. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry demonstrated a strong reaction in the majority of tumour cells. Thus, the immunotherapy with nivolumab was implemented. At the latest follow-up, 6 months post lymphadenectomy and 2.5 years since lymphadenopathy onset, the patient remained alive, asymptomatic, and disease-free.

Discussion

Ganglioneuroblastic differentiation in melanocytic neoplasms is an extremely rare phenomenon, with only 7 reported cases documented in the literature [5–11]. Among these cases, ganglioneuroblastic differentiation was observed in primary cutaneous lesions in 6 instances. Table 2 provides a summary of the literature cases.

Table 2

Summary of the cases of melanocytic neoplasms with ganglioneuroblastic differentiation reported in the literature

In our study, we report the first documented case of MUP exhibiting ganglioneuroblastic features, as well as the second case where ganglioneuroblastic elements were present in a lymph node metastasis. In a study by Banerjee et al. in 1999, ganglion cells and neuroblasts embedded in a fibrillar stroma were observed in lymph node metastases of melanoma, which was confirmed through immunohistochemistry and ultrastructural examination [5]. Notably, no evidence of divergent differentiation was detected in the primary tumour. Conversely, in a case described by Grayson et al., extensive ganglioneuroblastic features were only observed in the primary melanoma, while neither the local recurrence nor the affected lymph nodes displayed similar differentiation [8]. Interestingly, in another case, areas reminiscent of neuromatous stroma and focal positivity for neuron specific enolase and glial fibrillary acidic protein in ganglion-like cells were reported in a plexiform atypical Spitz tumour [11].

Our case presented an occult metastatic melanoma with a biphasic neoplasm composed of a spindle cell component and areas of ganglioneuroblastic differentiation. The spindle cell component exhibited positive staining for SOX10, a highly sensitive marker for melanoma, while classic melanoma markers HMB45 and melan-A were negative. Moreover, PRAME, a relatively novel marker for melanoma [12], which often displays strong expression at metastatic sites, showed positivity in our case. Molecular testing revealed an NRAS mutation, providing additional support for the diagnosis of melanoma. NRAS alterations are common in acral melanomas; however, the histopathological examination of resected subungual lesions was unavailable. Our case is the first to document a specific molecular abnormality in melanoma with ganglioneuroblastic differentiation.

When considering the differential diagnosis of melanoma with ganglioneuroblastic differentiation, possibilities such as a collision tumour with metastatic ganglioneuroblastoma, ectomesenchymoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, malignant rhabdoid tumour, malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumour, and rhabdomyosarcoma/triton tumour must be considered [1]. The first possibility was excluded based on clinical presentation, while the remaining entities were excluded through immunophenotyping, which revealed retained expression of H3K27me3 and INI1, as well as negative staining for desmin and MyoD1. Importantly, classic melanoma markers HMB45 and melan-A may be absent in melanocytic lesions with ganglioneuroblastic differentiation, underscoring the significance of this diagnostic pitfall. Notably, our study is the first to demonstrate SOX10 expression in this specific setting.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study presents a unique case of occult melanoma with ganglioneuroblastic differentiation, further contributing to the limited body of literature on this rare phenomenon. The identification of SOX10 positivity and NRAS mutation supported the diagnosis of melanoma in this case. It also highlights the crucial role of immunohistochemistry and molecular investigation in the diagnosis of melanomas with unusual histological features, and in identification of appropriate patients for immune checkpoint therapy. The infrequent phenomenon of ganglioneuroblastic differentiation in melanomas provides additional evidence supporting a shared histogenetic origin derived from the neural crest.