GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATM ENT OF ASTHMA IN CHILDREN UNDER 6 YEARS OF AGE

DEFINITION

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory bronchial disease characterized by symptoms of bronchial obstruction including expiratory wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and labored breathing. These symptoms can vary in severity and may resolve with medication or, in some cases, spontaneously. Inflammation, along with associated changes in airway structure and function, is considered a key factor in the development of asthma.

RISK FACTORS FOR ASTHMA

Bronchial obstruction episodes affect up to 50% of children under 6 years of age.

The risk of asthma diagnosis in this group of children increases when:

episodes of obstruction occur more than 3 times a year,

symptoms (cough, wheezing, difficulty breathing) associated with infection typically last longer than 10 days,

symptoms such as coughing, wheezing, and difficulty breathing may occasionally occur between infections, during play, or while laughing,

there is a personal history of allergies (sensitization, atopic dermatitis, or food allergies) or a family history of asthma.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of asthma is based on recognizing typical symptoms in the patient’s clinical history and physical examination, combined with confirmed reversibility of bronchial obstruction.

Considering the unique clinical presentation of asthma in preschoolers and the challenges in confirming obstruction reversibility, additional diagnostic criteria are often necessary:

history of at least 3 episodes of bronchial obstruction (expiratory wheezing, cough, shortness of breath, and laboredbreathing), with documented improvement after short-acting β2 agonists (SABA) administration; or even a single episode of obstruction with a severe course (requiring oral corticosteroids (OCS), hospitalization), with subsequent improvement after anti-asthmatic treatment,

physician-documented resolution of wheezing and other asthma symptoms following controller therapy or SABA, or alternatively, parental observation of improvement after 3 months of treatment with low-dose inhaled CS and as-needed SABA, or clear improvement after using SABA,

exclusion of causes of bronchial obstruction other than asthma.

Exacerbations occurring only during infections do not rule out an asthma diagnosis, but the risk is higher when bronchial obstruction also occurs regardless of infections.

A positive personal or family (in parents, siblings) history of atopy increases the likelihood of an asthma diagnosis, but is not required for the diagnosis (Figure 1).

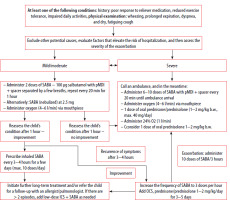

Figure 1

Algorithm for asthma treatment in children under 5 years of age (GINA 2024, KOMPAS POZ 2016)

ICS – inhaled corticosteroids, OCS – oral corticosteroids

Asthma in children can be diagnosed and treated by a primary care physician. In most cases, a detailed history and physical examination help rule out other diseases with a similar clinical presentation. If a diagnosis other than asthma is suspected, conducting a preliminary differential diagnosis at the primary care level is advisable. The scope of additional examinations depends on the clinical situation and may include: chest X-ray, and CBC with differential.

Consultation with a specialist is essential if there is any uncertainty about the diagnosis or if asthma is uncontrolled.

DIFFERENTIATION

Symptoms indicating an alternative diagnosis to asthma:

nutritional disorders,

symptoms occurring in the neonatal period or early infancy, particularly when accompanied by nutritional disorders,

vomiting along with respiratory symptoms,

chronic wheezing,

lack of response to anti-asthmatic treatment,

lack of association with factors that commonly exacerbate asthma, such as viral infections,

focal lung changes, heart disease, and clubbed fingers,

hypoxemia unrelated to viral infection.

TREATMENT

Long-term asthma treatment is generally initiated under two circumstances:

The history and symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of asthma. The initiated treatment should align with the second step in the stepwise approach to asthma management. Long-term treatment may also be considered for children with less frequent symptoms but a more severe disease course. Evaluating the response to therapy is always essential.

The diagnosis of asthma is uncertain, but the child frequently (more than every 6–8 weeks) requires treatment with SABA or antibiotics. In such cases, treatment takes the form of a therapeutic trial, with an evaluation of therapeutic response after 2–3 months to confirm or exclude an asthma diagnosis. In these situations, consulting an allergist or pulmonologist is highly recommended.

Based on the assessment of asthma control, adjustments to treatment – whether escalation or de-escalation – should follow the scheme outlined in Figure 1.

The first-line drugs for long-term management are inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) administered daily at the lowest effective dose. Table 1 presents low doses of ICS for children under 6 years of age, based on the GINA 2024 guidelines (with own modifications).

Table 1

Low doses of inhaled corticosteroids for children under 6 years of age (based on GINA 2024 guidelines, with own modifications)

The choice of treatment depends on the patient’s age and the treatment options available for that age group. Individual patient preferences must also be taken into account.

Table 2 outlines the available methods of inhaled therapy for children under 6 years of age, according to GINA guidelines.

Table 2

Selection of inhaled therapy in children under 6 years of age according to GINA

Evaluation of treatment response and adjustment should occur at each medical visit, every 3–6 months. After any change in therapy, a follow-up visit should be scheduled within 3–6 weeks. Asthma control can be evaluated based on the criteria outlined in Table 3.

Table 3

Criteria for asthma control in children

Since SABAs are the only bronchodilator treatment option available for this age group, it is crucial to monitor their use closely to prevent overuse. To reduce the risk of SABA monotherapy, it is recommended to add ICS whenever SABA use is required. Using SABA more than twice a week indicates the need to escalate anti-inflammatory treatment and seek specialist consultation.

ICS IN COMBINATION WITH LABA IN CHILDREN UP TO 6 YEARS OF AGE

Access to treatment with ICS and LABA combination for children is limited. The lack of sufficiently reliable studies demonstrating the safety and efficacy of the therapy in younger children restricts its use to those aged 4 and older, available as a combination of fluticasone and salmeterol.

MONTELUKAST

Montelukast can be used either as monotherapy, which is a less effective option than ICS, or as an add-on to ICS, where it is less effective than LABA. Prescribing montelukast should always be preceded by an assessment of the benefit-risk ratio. In patients with neuropsychiatric disorders (particularly anxiety and/or sleep disorders) occurring before or during montelukast treatment, the benefit-risk ratio does not support the use of this medication. Discontinuation of montelukast sodium may be associated with partial loss of symptom control, which should be considered when making adjustments to the treatment regimen.

GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF ASTHMA IN CHILDREN UNDER AGED 6–11

DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

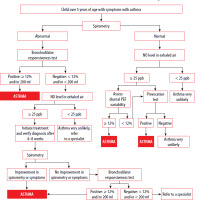

The definition of asthma in children aged 6−11 years is the same as in adolescents and adults. The diagnosis of asthma should be considered if a child presents with recurrent episodes of dry, fatiguing cough, expiratory wheezing, shortness of breath, or attacks of dyspnea, with symptoms resolving either spontaneously or with appropriate treatment. The diagnosis is made based on the presence of symptoms consistent with asthma and the results of additional tests (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Algorithm for the diagnostic management of children over 5 years of age with symptoms consistent with asthma (according to ERJ, 2021). Abnormal result − bronchial obstruction

Diagnosis of asthma can be confirmed based on:

positive bronchodilator responsiveness to inhaled salbutamol,

elevated exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) level and:

Option 2 applies to children with normal spirometry results or a negative bronchodilator responsiveness test.

The differential diagnosis should include chronic upper airway cough syndrome, foreign body aspiration, bronchiectasis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, congenital heart disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis, and other less common conditions.

SPIROMETRY AND PEF MEASUREMENT

Spirometry is the most important test in the diagnostic process of asthma in children over 5 years of age (Figure 2). Spirometry must be performed using certified equipment by trained medical personnel. At a minimum, forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC are assessed. Spirometry should be performed at the start of treatment, after 3–6 months of asthma controller therapy (to assess the patient’s personal best FEV1) and thereafter at least every 6–12 months, depending on the clinical course of asthma.

In children diagnosed with asthma, PEF measurements are important for assessing treatment response (asthma control), identifying exacerbating factors, and monitoring exacerbations in various settings (at home, in the emergency department, on the hospital ward). PEF monitoring is particularly recommended for patients with severe asthma.

OTHER ADDITIONAL TESTS

The key tests for asthma diagnosis include spirometry with bronchodilator responsiveness test, FeNO measurement, and evaluation of PEF variability (Figure 2). Allergy tests (skin prick testing, measurement of sIgE and total IgE levels) have no diagnostic value; they merely confirm the presence of atopy.

Chest X-ray is not essential for the diagnosis of asthma and should not be performed on a routine basis. However, it may be recommended for patients with diagnostic uncertainties or in some cases of severe disease exacerbation.

ASTHMA COMORBIDITIES

The most common asthma comorbidities include allergic rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, atopic dermatitis, obesity, dysfunctional breathing, vocal cord dysfunction syndrome, depressive disorders, gastroesophageal reflux, and less commonly other diseases. Comorbid conditions can pose significant challenges in diagnosing and treating asthma in children.

ASTHMA CONTROL

The concept of asthma control is similar to that in adults (see above). In everyday practice, the simple and quick Asthma Control Test (ACT) can also be used (available at https://www.nfz.gov.pl/download/gfx/nfz/pl/defaultaktualnosci/229/4636/1/test_kontroli_astmy_dla__dzieci_w__wieku_od_4_do_11_lat.pdf.) (Table 4).

Table 4

Criteria of asthma control for children aged 6–11 years (GINA)

ASTHMA PHARMACOTHERAPY − LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT

The foundation of asthma treatment in children is disease-controlling medications including ICS, montelukast, LABA, and as-needed medications: SABA and OCS (exacerbations). In addition to pharmacotherapy, educating the child and their caregivers, eliminating exacerbating factors, and allergen-specific immunotherapy are key components of treatment.

The preferred method for administering asthma medications is aerosol therapy. The recommended method of inhaled therapy for children over 5 years of age is through a dry powder inhaler (DPI) or a pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) with a spacer. Nebulization is an alternative method in most cases, except during severe asthma exacerbations (when there is no improvement after using pMDI medications), pMDI intolerance, or when the medication is only available in nebulized form.

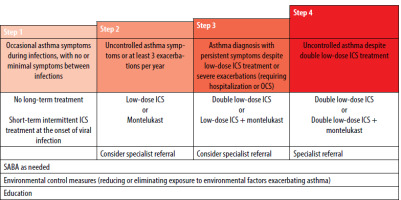

The algorithm for stepwise asthma treatment in children aged 6−11 years is presented in Table 5.

Table 5

Stepwise asthma treatment for children aged 6–11 years (GINA)

As-needed management at each stage of therapy is SABA, with MART also included in steps 3 and 4. Children requiring step 4 or 5 therapy should not be managed in primary care.

The initial treatment regimen depends on the severity of baseline asthma symptoms (Table 6).

Table 6

Preferred initial treatment of asthma in children aged 6−11

The child should be referred to a pulmonologist or allergist in cases of diagnostic difficulties (Figure 2) and when asthma is not controlled and treatment at step 4 or 5 is necessary.

MANAGEMENT OF ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

The selection of appropriate asthma exacerbation management in an outpatient setting, emergency room, or hospital ward is based on assessing its severity through physical examination and SpO2 measurement (or alternatively, PEF measurement or spirometry).

The most crucial part of this management is the initial treatment (during the first hour), which involves repeated clinical assessments and verification of the indications for hospitalization. The primary medications are SABAs delivered via pMDI with a spacer (first-line treatment) and OCS (second-line treatment). Nebulized SABA, or SABA with an anticholinergic, is not recommended as first-line therapy (Figure 3).

Indications for hospitalization of a child with an asthma exacerbation include moderate exacerbation despite appropriate outpatient treatment (no response after 1 hour of initial therapy), any severe exacerbation, SpO2 ≤ 91%, persistent tachycardia with cyanosis, intolerance to fluids or oral medications, lack of compliance from parents/guardians, social factors, and the presence of serious comorbidities.

STANDARDS FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF ASTHMA IN ADULTS

DEFINITION

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease entity defined by the presence of persistent airway inflammation and typical clinical symptoms. Chronic inflammation leads to bronchial hyperresponsiveness, causing shortness of breath, chest tightness, coughing, and wheezing. Features of obstruction on respiratory function tests and clinical symptoms are typically variable over time, with fluctuating severity.

WHEN SHOULD ASTHMA BE SUSPECTED?

Asthma most commonly develops in children and adolescents with other coexisting allergic conditions (history of allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis). Asthma should be suspected in patients presenting with symptoms including shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, or chest tightness. Symptoms typically worsen following exposure to allergens, during viral infections, after physical exertion, following exposure to cigarette smoke, air pollution, cold air, or other irritants. Symptoms occur usually at night or in the early morning. Asthma can also develop in adults (late-onset form) and is often associated with conditions such as obesity, chronic sinusitis, and hypersensitivity to aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In both adults and children, attention should be given to frequent, recurrent, and persistent viral respiratory tract infections with bronchial obstruction that do not resolve with symptomatic treatment, as they may indicate viral exacerbations of undiagnosed and untreated asthma.

A specific subgroup of patients suspected of having asthma includes those with a predominant cough, including those with a ‘suffocating’ cough. In these patients, a detailed history should be taken, focusing on symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), particularly the symptom of post-nasal drip or its equivalent (‘throat-clearing’). If asthma is suspected in these patients, treatment should begin with intranasal corticosteroids. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) should not be introduced automatically due to the risk of hindering further asthma diagnostics. A SABA can be prescribed on an as-needed basis, as it does not interfere with asthma diagnosis, until consultation at a specialized center for bronchial asthma diagnosis and treatment, ideally one with access to bronchial hyperresponsiveness tests, such as methacholine challenge test.

WHO CAN INITIATE ASTHMA TREATMENT?

Asthma treatment should be initiated by a physician experienced in the diagnosis and management of asthma, as accurate diagnosis can be challenging. This can primarily be performed by specialists in pulmonary diseases or allergology, as well as by healthcare professionals from other specialties who have experience in diagnosing and treating asthma, such as those in family medicine, internal medicine, or emergency medicine. If asthma is diagnosed by a medical professional, the patient should receive a prescription for reimbursable medications [ICD-10 code: J45].

WHAT DETERMINES ASTHMA DIAGNOSIS?

The foundation for an accurate asthma diagnosis is a detailed medical history, which includes evaluating the occurrence of typical symptoms, their variability over time, and the presence of coexisting allergic conditions. It is recommended to confirm airway obstruction through physical examination (auscultatory wheezing and rhonchi) and assess the variability of obstruction with respiratory function tests (bronchodilator responsiveness test, PEF measurement over time). Additional tests confirming the allergic etiology of the symptoms, such as skin prick tests and serum sIgE testing, are helpful.

WHEN IS IT LIKELY THAT THE PATIENT DOES NOT HAVE ASTHMA?

Isolated respiratory symptoms such as chronic cough, productive cough with purulent sputum, dry cough in a patient on ACE inhibitors, dyspnea with signs of heart failure, chest pain, inspiratory stridor, lack of symptom variability and absence of typical disease exacerbating factors, as well as the onset of symptoms in elderly individuals, are not characteristic of asthma. The absence of clinical improvement despite anti-inflammatory treatment should raise doubts as well, provided the patient’s adherence to treatment guidelines and correct inhalation technique have been confirmed. In such cases, the diagnostic process should be broadened in line with the principles of differential diagnosis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Asthma should be differentiated from other causes of paroxysmal dyspnea and wheezing. The most common causes to consider include COPD, asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, circulatory failure, bronchiectasis, pulmonary embolism, upper airway cough syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, foreign body aspiration, inducible laryngeal obstruction, cystic fibrosis, hyperthyroidism, cancers (lung cancer and others, including Hodgkin’s lymphoma), and interstitial lung diseases. Dysfunctional breathing, hyperventilation, and drug-induced coughing should also be considered. Furthermore, it is important to be mindful of psychosomatic disorders that may present as abnormal dyspnea.

WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON ASTHMA COMORBIDITIES?

Allergic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, non-allergic rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, COPD, obesity, and hypersensitivity to aspirin and other NSAIDs.

WHEN SHOULD SPIROMETRY BE PERFORMED?

An indication for spirometry is the presence of respiratory symptoms, particularly wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, chest tightness.

In patients with a typical history of asthma symptoms, when spirometry is not immediately available, bronchial asthma can often be diagnosed without spirometric confirmation. However, without this examination, it is difficult to be certain that the clinical diagnosis is accurate.

Bronchodilator responsiveness testing should be performed regardless of the baseline FEV1 (even if it exceeds 100% of predicted value). It is recommended to perform resting spirometry and a bronchodilator responsiveness test 20 min after inhaled administration of 400 µg of salbutamol. An improvement in FEV1 of ≥ 12% from baseline or ≥ 200 ml indicates a positive bronchodilator responsiveness test, which, along with consistent clinical symptoms, supports the diagnosis of bronchial asthma. A single spirometry test is not sufficient for diagnosing asthma. A negative bronchodilator responsiveness test does not rule out the diagnosis of asthma.

HOW OFTEN SHOULD SPIROMETRY BE PERFORMED?

In patients with asthma, spirometry should be performed at least once a year and at each medical follow-up if there are concerns about disease control.

HOW AND WHY SHOULD PEF BE MONITORED?

PEF measurement is a reliable indicator of poor asthma control. PEF should be measured in the following circumstances: uncertainty about the diagnosis, and uncertainty about disease control.

PEF measurements should be performed in the morning and evening, prior to taking anti-asthmatic medications. The patient should record the results in a diary.

Diurnal PEF variability > 10% on 2 consecutive days may indicate poor asthma control.

WHEN SHOULD A CHEST X-RAY BE ORDERED?

Chest X-ray should be routinely ordered for adult patients with suspected asthma. Chest X-ray plays a role in comprehensive differential diagnosis and should always be conducted when there is uncertainty about the final diagnosis. For patients diagnosed with asthma, routine chest X-ray examinations are not recommended at each follow-up visit.

WHAT OTHER TESTS ARE IMPORTANT FOR DIAGNOSING ASTHMA?

Bronchial provocation tests (with methacholine, mannitol, histamine, or exercise) may be helpful in the differential diagnosis. In cases of diagnostic uncertainty, the most effective test for confirming or ruling out asthma is bronchial provocation test with methacholine. The primary issue is the limited availability of this test.

An important diagnostic tool for asthma and the assessment of disease control is measuring peak expiratory flow (PEF). A 20% improvement in this parameter after SABA administration supports the diagnosis of asthma. Diurnal PEF variability exceeding 10% is an indicator of poor asthma control. It can also serve as a basis for diagnosing asthma when spirometry is not available, although it has lower sensitivity.

Measuring the fractional concentration of exhaled nitric oxide in adults has limited value for diagnosing asthma. It may be useful for determining asthma phenotype. Patients with FeNO > 50 ppb typically respond well to treatment with ICS.

Skin prick testing is not used to diagnose asthma; however, it is useful in identifying asthma phenotype. Evaluating serum levels of specific IgE has comparable significance. The evaluation of total IgE levels is not considered clinically significant.

ASTHMA CONTROL − WHAT IS IT?

Asthma control is assessed in two domains:

asthma symptom control − basic level, involving evaluation of the severity of asthma symptoms and the presence of sleep disturbance and limitation of physical activity caused by asthma,

risk factors for adverse asthma treatment outcomes − additional level, involving evaluation of the risk of exacerbations, irreversible airflow limitation, and adverse drug reactions.

Assessment of the risk of exacerbations must incorporate an evaluation of comorbid conditions associated with asthma.

IS MY PATIENT’S ASTHMA WELL-CONTROLLED?

The patient should be asked the questions listed below. The questions refer to the 4 weeks leading up to the medical assessment.

Another option is to use the Asthma Control Test (ACT).

Furthermore, the patient did not experience frequent severe exacerbations (at least two requiring the initiation of OCS) or a severe exacerbation treated in a hospital setting in the past year.

HOW TO INITIATE ASTHMA TREATMENT?

Asthma treatment should start with low-dose ICS and as-needed SABA reliever. An alternative strategy, which more effectively reduces the risk of exacerbations, involves using a combination of low-dose ICS/formoterol twice daily, along with as-needed ICS-formoterol.

WHY NOT INITIATE ASTHMA TREATMENT WITH SABAS?

The treatment shouldn’t be initiated with SABAs, because the patient views this as the foundation of asthma treatment, which leads to not using ICS. Regular use of SABA without appropriate anti-inflammatory treatment increases bronchial hyperresponsiveness and the risk of hospitalization and death.

HOW TO ESCALATE/DE-ESCALATE ASTHMA TREATMENT?

Asthma control should be evaluated at every patient visit (refer to section 14 above). If asthma is poorly controlled despite correct use of anti-asthmatic medications, an escalation to the next level of treatment should be considered. If the patient has maintained good asthma control for 3 months, a de-escalation to a lower therapeutic level should be considered.

The therapeutic levels in asthma are as follows:

as-needed low-dose ICS in combination with formoterol or as-needed SABA in combination with as-needed ICS (neither of these treatment modalities is approved in Poland),

low-dose ICS on a regular basis and as-needed SABA,

low-dose ICS in combination with LABA twice daily and as-needed SABA or low-dose ICS/formoterol twice daily and as-needed ICS/formoterol,

A) medium- or high-dose ICS/LABA,

B) LAMA/LABA/ICS combination inhaler,

LAMA/LABA/ICS combination inhaler plus add-on treatment (LTRA, OCS or biologic medications).

Patient education, particularly regarding the correct administration of inhaled medications, is a critical component of comprehensive asthma management. A written asthma action plan, which includes adjustments for treatment escalation or de-escalation, procedures for managing exacerbations, and conscious adherence − especially in documenting symptoms and (potentially) measuring PEF − greatly improves the effectiveness and safety of therapy. It is also necessary to schedule follow-up visits. Repeat prescriptions for asthma medications by a nurse are not recommended.

WHEN SHOULD AN ASTHMA EXACERBATION BE CONSIDERED?

Asthma exacerbation is defined as a progressive increase in asthma symptoms including shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, and chest tightness, along with a deterioration of ventilation parameters (PEF, FEV1), necessitating a change in treatment.

Severe asthma exacerbation is defined by the patient’s clinical condition, characterized by severe asthma symptoms from the onset or no improvement despite exacerbation treatment for more than 48 hours.

Exacerbations typically result from exposure to environmental factors (such as viral respiratory infections, allergens, or inhaled irritants) and/or non-adherence to the doctor’s prescribed medication regimen. However, asthma exacerbations can sometimes occur without an apparent cause. Exacerbations, including severe ones, can also arise in patients with mild to moderate asthma.

HOW TO MANAGE ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS?

If an asthma exacerbation is suspected or confirmed, it is important to assess the severity of the exacerbation, the potential risk of death, the duration and nature of the symptoms, and the treatment administered to date. The physical examination should also evaluate the patient’s vital signs, the nature, severity, and degree of control of any comorbidities, and, as indicated, assess oxygen saturation and PEF parameters. The therapeutic approach involves increasing the frequency of as-needed medications and temporarily intensifying primary asthma treatment, chiefly by increasing the doses of ICS.

Severe asthma exacerbations are treated with OCS (methylprednisolone at 32 mg for 5 days). If improvement is observed, OCS at this dose can be discontinued immediately without the need for gradual tapering. Some patients experiencing severe asthma exacerbations may require treatment in the emergency department or hospital.

WHEN SHOULD DIFFICULT-TO-TREAT ASTHMA BE CONSIDERED?

Difficult-to-treat asthma is characterized by poor control despite treatment with moderate to high doses of ICS/LABA or the need for regular treatment with OCS. Difficult-to-treat asthma should also be suspected if ongoing high-dose ICS or maintenance treatment with OCS is necessary to achieve good symptom control and reduce the risk of exacerbations. In such patients, it is essential to verify the diagnosis of bronchial asthma and exclude other potential causes of poor disease control. Typically, it is the presence or poor control of comorbidities (usually chronic sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, depression, and anxiety), as well as repeated exposure to allergens and/or irritants, including smoking. It is also essential to rule out poor inhalation technique or failure to adhere to the prescribed treatment, as well as the impact of adverse reactions and overuse of inhaled medications, particularly SABAs.

WHEN SHOULD SEVERE ASTHMA BE CONSIDERED?

Severe asthma is a subset of difficult-to-treat asthma where, despite improvements in treatment adherence, inhalation techniques, and the modification of other factors that worsen asthma control (as detailed in section “When should an asthma exacerbation be considered?”), the condition remains uncontrolled. Severe asthma is defined by inadequate symptom control despite optimizing treatment with high doses of ICS/LABA and ruling out other factors that could impair disease control (as listed above), or by the need to maintain high doses of medications to achieve good symptom control and reduce the risk of exacerbations.

Patients suspected of having severe asthma should be referred to experienced, highly specialized centers with expertise in this field. Diagnosing severe asthma requires a comprehensive differential diagnosis, including the exclusion of other potential causes of peripheral eosinophilia. It is essential to assess the clinical phenotype of the disease to determine patient eligibility for biologic treatment, including factors such as allergic etiology, peripheral or sputum eosinophilia, and exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels. Severe asthma affects 3–10% of the asthma population.

WHEN SHOULD PATIENTS BE REFERRED TO A SPECIALIST, AND WHICH SPECIALIST SHOULD BE CONSULTED (PULMONOLOGIST, ALLERGIST, OTOLARYNGOLOGIST, GASTROENTEROLOGIST, DERMATOLOGIST)?

The differential diagnosis of bronchial asthma, as well as insufficient disease control during treatment − particularly in cases of difficult-to-treat or severe asthma − require critical verification of the diagnosis and a thorough assessment of the presence and degree of control of comorbidities. Patients with suspected chronic sinusitis and cough as the dominant symptom present a particular challenge and should be evaluated by experienced specialists before the initiation of ICS treatment.

It is important to consider the indications for specialist consultation in the following areas:

pulmonology: primarily the above-mentioned patients with predominant symptoms of cough or ‘suffocating’ cough, and also to exclude other respiratory pathologies, particularly COPD, bronchiectasis, interstitial lung diseases, thoracic cancers, pulmonary embolism, bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, and severe α1 antitrypsin deficiency; each of these conditions may present with symptoms similar to asthma, including paroxysmal dyspnea, chronic or paroxysmal cough (dry or productive), and wheezing,

allergology: for the comprehensive diagnosis of the allergic etiology of symptoms, including triggers of rhinitis and chronic sinusitis, as well as hypersensitivity to NSAIDs,

laryngology: for the evaluation of chronic sinusitis, seasonal or chronic rhinitis, laryngeal obstruction, and vocal cord dysfunction,

gastroenterology: due to the frequent coexistence and challenges in managing symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, as well as parasitic infections of the gastrointestinal tract.

ROLE OF ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION IN ASTHMA

Environmental pollution, particularly PM2.5 particles, but also particles from diesel engines, suspended dust, and NO and SO2 in the atmospheric air, worsens asthma control and increases the risk of exacerbations.

Air purifiers may have a modest beneficial effect on asthma control; however, due to the low quality of clinical trials, their use as an adjunctive treatment for asthma cannot be definitively recommended.

ALLERGEN-SPECIFIC IMMUNOTHERAPY IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ASTHMA

Allergen-specific immunotherapy, supervised by an allergist, is recommended for patients with allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. It can be used in individuals with well-controlled asthma. Allergen-specific immunotherapy serves an add-on therapy to the ongoing pharmacological treatment for asthma. It is particularly recommended for patients with allergies to grass pollens and house dust mite. It helps reduce the frequency of exacerbations, improves asthma control, and decreases the need for emergency medication. In addition, it allows for a reduction in the doses of controller medication. Allergen-specific immunotherapy used in patients with allergic rhinitis but without asthma can significantly reduce the risk of developing asthma.

Subcutaneous immunotherapy seems to be the most effective modality, while data on sublingual immunotherapy are less conclusive. Immunotherapy should only be initiated if FEV1 > 70% of predicted value.

VACCINATIONS AND ASTHMA

All asthma patients should receive an annual influenza vaccine and a one-time dose of the advanced pneumococcal vaccine. Annual COVID-19 vaccination and RSV vaccination are also recommended for patients over 50 years of age.

COVID-19 AND ASTHMA

Most asthma patients who follow their medication regimen regularly tend to experience a milder course of COVID-19 compared to individuals without asthma. However, patients with severe asthma seem to be at higher risk of severe COVID-19 and mortality.

Individuals with asthma, regardless of the severity of the condition or associated allergies, including food allergies, should receive the full course of COVID-19 vaccination. Patients with a history of anaphylaxis should be vaccinated under heightened medical supervision.