Thoracic endometriosis syndrome (TES) is a complex phenomenon of symptoms related to the occurrence of functional ectopic endometrial tissue in the thoracic cavity, most commonly found in lung parenchyma, pleural surfaces and the diaphragm. There are various presentations of TES, such as haemoptysis, pneumomediastinum, lung nodules, haemothorax, isolated chest pain and more. The common clinical presentation is catamenial pneumothorax (CP) – a type of recurring pneumothorax that occurs 24 hours prior or 72 hours after the onset of menses in women, mostly in child-bearing age. Catamenial pneumothorax reoccurring in usually infertile women with thoracic endometriosis rarely co-exists with pregnancy. The burdensome and unpredictable character of catamenial pneumothorax should be taken into consideration while taking care of the pregnant woman.

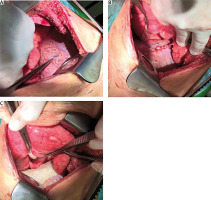

We report a case of a 35-year-old never-smoking woman who experienced a right-sided pneumothorax during the delivery. The patient had a medical history of 2 previous events of pneumothorax. The first episode of right-sided pneumothorax was associated with physical activity. The symptoms of pneumothorax were: slight pain and discomfort in the chest. The patient was treated with a chest tube successfully. After a year, the pneumothorax relapsed during a menstrual period with characteristic and previously recognizable symptoms. On computed tomography, there were no apparent abnormalities in the pulmonary parenchyma, apart from pneumothorax (Figure 1). Due to the recurrent symptomatic character of the disease, the patient was accepted for videothoracoscopic operative treatment. Intraoperatively, numerous diaphragmatic perforations were diagnosed. The apex of the lung was excised, and a pleurectomy was performed. The third episode of pneumothorax was diagnosed 3 weeks after a vaginal delivery. The symptoms were repeatedly recognized by the patient from the early moment of delivery. The woman complained of a squeezing sensation and undefined mild pain in the chest, predominantly on the right side. She was not dyspnoeic and was otherwise asymptomatic. As she recognized the symptoms as recurrent pneumothorax, she did not complain about this condition in order to continue with the delivery. The reason for that was her understanding of the well-being of the child. The delivery was otherwise uneventful, with no signs of hypoxia to the child. After discharge from the hospital the symptoms of pneumothorax did not diminish. Three weeks afterwards, she was admitted to the thoracic surgery department. Chest computed tomography did not show any abnormalities other than pneumothorax. The patient was referred for open surgery. During the lateral, muscle-sparing thoracotomy, many adhesions were seen on the apex of the lung. Numerous fenestrations were present in the central tendon of the diaphragm (Figure 2 A). The pleura was rinsed with povidone-iodine and checked for air leaks. The diaphragm was sutured with Ticron 5 (Figure 2 B) and then covered with TachoSil (Takeda) (Figure 2 C). The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient remained free of recurrence during the follow-up period. Three years after the procedure, the patient became pregnant. After an uneventful pregnancy, she gave birth by caesarean section. This delivery was uncomplicated. Expansion of lungs was confirmed on an X-ray at discharge from the maternity ward.

Figure 2

A – Intraoperative finding of diaphragmatic perforations. Repair of the diaphragm with Ticron 5 suture (B) and reinforced with TachoSil (Takeda) (C)

The most common theory of the mechanism of catamenial pneumothorax is associated with rupture of the focus of endometriosis located in the pulmonary parenchyma. This occurs in the period related to menses. Another mechanism is related to the passage of air from the uterus and fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity and through the pathological foramina in the diaphragm. This occurs in the patient with endometrial foci located in the tendinous part of the diaphragm. Menses cause repeated erosion of the diaphragm, resulting in its multifocal destruction. In our patient, the association of pushing during vaginal delivery in a patient with coexisting perforations in the diaphragm is the most likely reason for the accumulation of air in the pleural cavity. On the other hand, this may also occur during a caesarean section if the peritoneal cavity is open. Based on the reported case, we would like to emphasize that recurrent pneumothorax in pregnant women may be associated with an increased risk of pneumothorax occurring during delivery. The symptoms do not have to be related to the dyspnoea and respiratory compromise. Most commonly, right-side dull, mild or intense pain related to breathing is the most common symptom. Previous surgical treatment of pneumothorax does not have to prevent the recurrence during delivery. Therefore, a patient with a history of recurrent catamenial pneumothorax should deliver in centres with personnel trained to treat pneumothorax adequately. Since this is a rare medical situation, there are no guidelines concerning the mode of delivery in women with recurrent pneumothorax. A recent literature review on spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy recommended shortening the second stage of labour. Vaginal delivery is not contraindicated after definitive treatment of pneumothorax, but hyperventilation and the Valsalva manoeuvre during labour may increase the risk of recurrence. Elective-assisted delivery (forceps or ventouse extraction) and regional anaesthesia at or near term to decrease maternal expulsive efforts during the second stage of labour are suggested [1, 2]. Yoshioka et al. reported efficient treatment of catamenial pneumothorax related to pregnancy by thoracoscopic resection and pleurodesis [3]. To our knowledge, catamenial pneumothorax related to delivery has never been reported in the literature. On surgery we decided to use a sealant (TachoSil, Takeda Austria GmbH), which may contribute to an improved operation effect and could be recommended due to the recently observed feature of creating dense local pleural adhesions. In the case of full-thickness diaphragmatic defects, the question whether to excise the defect or directly repair it remains open. Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is the gold standard approach to catamenial pneumothorax and may also be recommended in patients requiring diaphragmatic reconstruction, including for redo cases. Magnetic resonance imaging may be an appropriate diagnostic method to diagnose diaphragmatic endometrial implants but may be insufficient to adequately map the distribution and size of diaphragmatic defects. Any history of endometriosis and occurrence of right-sided pneumothorax in the period of menses should raise suspicion of catamenial pneumothorax. After the surgery, hormonal therapy should be considered as combined treatment lowers the rate of pneumothorax recurrence [4–7]. Garner et al. analysed 7 papers regarding GnRH analogues and surgical treatment. Six of them reported a reduction of recurrences of CP, and the pooled recurrence rate of surgical intervention followed by GnRH analogue treatment was 3.4% [4]. However, Subotic et al., mentioned in Garner’s paper, described a series of 4 cases in which none of the patients received hormonal treatment and there was no recurrence within the follow-up of 6–43 months [8]. Elsayed et al. in 2022 performed a meta-analysis aiming to determine whether hormonal manipulation reduces the recurrences of CP. The risk of recurrence in the group with hormonal treatment was 17.3%, whereas without this intervention it was 54.2% [5]; most of those patients received GnRH agonists. Another treatment option is administration of dienogest. It has been found that dienogest may have similar effectiveness as GnRH analogues, but reduces long-term side effects, such as lower bone density [7].

A history of catamenial pneumothorax may increase the risk of delivery-related pneumothorax. These patients require a multispecialty team approach. Patients with pneumothorax related to diaphragmatic perforations should undergo efficient reconstruction to avoid pneumothorax during delivery.