Introduction

Myocardium has limited proliferative capacity and adult hearts are considered incapable of regenerating after injury [1, 2]. A large loss in the viable myocardium eventually diminishes the heart’s ability to contract synchronously, leading to heart failure (HF). In Poland, HF affects about one million people, and an additional 250,000 cases are predicted over the next 25 years [3]. The prevalence of underlying causes for HF vary across the world; however, ischemic heart disease (IHD) is the most common one in Europe and North America [4]. Despite unquestionable progress in medical therapies and revascularization over the last 3 decades [5–7], the problem of ischemic heart failure is increasing, and is projected to further increase in the next decades [8].

Myocardial revascularization is known to effectively relieve angina and improve exercise capacity and quality of life [9]; however, some myocardial regions may be ineligible for direct revascularization due to the lack of a proper target vessel or lack of viability. Therefore, surgical techniques designed to restore myocardial contractility have their limits. Excluding infrequently performed procedures such as the Dor (pericardial-lined Dacron endoventricular circular plasty) and Batista (reduction ventriculoplasty) procedures, the only option beyond left ventricle assist device implantation is heart transplantation [10, 11].

Nevertheless, despite the undoubted development in conventional, both interventional and pharmacological, strategies, there is still a great number of patients who experience significant IHD and HF symptoms. For these individuals, treatments that stimulate myocardial regeneration can offer alleviation of dyspnea and angina, and improvement in quality of life. Therefore, this subgroup of patients has been the most investigated one in regard to regenerative approaches over the last decades. However, based on the recent European Society of Cardiology guidelines, larger randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and registries are still required to define the role of additional treatment modalities to decrease non-responder rates and ascertain benefit beyond potential placebo effects [12].

In general, the scientific interest in regenerative medicine arose from fundamental studies, which showed that some vertebrates can regenerate myocardium throughout life. Orchestrated waves of inflammation, matrix deposition and remodeling, cardiomyocyte proliferation and tissue architecture restoration are commonly seen in heart regeneration models, including neonatal mice [13].

Although various approaches for regenerative treatment delivery have been studied, cardiosurgical access in the only one that allows direct delivery to the desirable part of the myocardium. In general, cardiac surgery allows the heart to be accessed through median sternotomy (Figure 1 A), ministernotomy (Figure 1 B) or left minithoracotomy (Figure 1 C). However, as studies on regenerative therapies show, minimally invasive approaches seem to be preferred. This review summarizes these hybrid techniques for regenerative treatments. An electronic search of MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Library and ClinicalTrials.gov databases was performed on 15th July 2022 to identify relevant articles using the following key words: guided tissue regeneration, cardiac regeneration, cardiac surgery, surgical delivery, cardiac tissue engineering, bioprinting, stem cells, scaffold, biomaterial.

Stem cell-based therapies

Stem cells are known to promote neovascularization and endothelial repair. Various cell populations such as bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (BM-MSCs), mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), CD34+, CD133+, endothelial progenitor cells, and adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (ADSCs) have been investigated so far [14–17]. MSCs along with other pluripotent stem cells have been proven to effectively stimulate angiogenesis and cardiac regeneration. BM-MSCs have been commonly used in stem cell-based therapies because of their wide availability and multipotency. ADSCs have been acknowledged for the feasibility and safety of repeated harvest and proliferation capacity that does not decline with aging.

Intracoronary stem cell delivery

The first evaluations of the efficacy of intracoronary stem cell delivery were not promising. Intracoronary infusion of BM-MSCs did not improve left ventricle (LV) function after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) despite concomitant successful angioplasty of the infarct-related artery [18]. Similar conclusions were made after the results of intracoronary infusion of allogeneic cardiac stem cells (CDCs) were published (ALLSTAR trial) [19]. The technique was considered safe, but it did not confirm the hypothesized scar size reduction in patients with post-MI LV dysfunction. On the other hand, the CIRCULATE-AMI trial with MSCs showed significant improvement in myocardial contractility and LV remodeling inhibition but only at 3 years follow-up, contrary to nonsignificant changes found 12 months following the procedure [20, 21]. However, this observation may arise from the stem cell line used rather than the prolonged observation period, as consistent results were obtained in other studies with umbilical cord MSCs [22, 23].

Nevertheless, despite initial disappointments with intracoronary stem cell delivery, new trials have been designed to investigate the potential feasibility of intracoronary infusion during cardiac surgery. SCIPIO was a first-in-human, randomized placebo-controlled trial to assess the safety of autologous c-kit(+) CSC delivery in patients with IHD and HF undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (NCT00474461). CSCs were isolated from the right atrial appendage after being harvested and processed during surgery. Isolation of CSCs from cardiac tissue was proven to be feasible in the operating room and did not alter practices during CABG. Most importantly, cardiac magnetic resonance showed that patients treated with intracoronary CSC infusion experienced a striking improvement in both global and regional LV function, a reduction in infarct size, and an increase in viable tissue that was present at both 4- and 12-month follow-up [24].

Whether the controlled infusion on a non-beating heart or the cardiac origin of stem cells was responsible for the success of this approach remains an issue to be solved by future studies. Although still awaiting results, similar design with intra-CABG c-kit(+) CSC infusion has been proposed by Sakakibara Heart Institute recently (NCT03351400). Moreover, the potential feasibility of another delivery route, via trans-bypass graft, is to be examined in a subgroup of patients in an ongoing randomized placebo-controlled trial with the use of CardioCell (Regeneration of Ischemic Damages in Cardiovascular System Using Wharton’s Jelly as an Unlimited Source of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine; NCT03418233).

Direct myocardial stem cell implantation

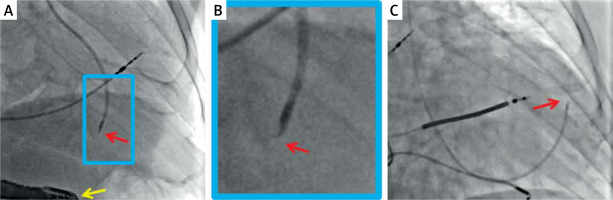

The idea to directly implant cardiomyocytes into the injured area was initially tested in animal models. Contrary to adult cardiomyocytes, which did not survive under any conditions, fetal and neonatal cells formed new and mature myocardium in inbred rats [25]. The procedure can be done either under direct vision, usually using minimally invasive surgical access (Figure 1 C) or percutaneously (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Typical radiographic images of percutaneous trans-endocardial delivery of stem cells using a dedicated, steerable catheter with a curved needle (red arrow) that has an adjustable length and possesses side holes. Effective anchoring of the needle in the target site is confirmed with a minimal contrast injection. The delivery is performed to pre-specified myocardial segments (based on their viability and thickness) under transesophageal echo control (A, yellow arrow) or using an LV-gram-based myocardial map integrating information from echocardiography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (C). Examples show standardized cell suspension (cocktail with pro-angiogenic factors) delivery to a pre-specified site in the inferior wall (A) and anterior wall (C). B is a close-up of A. The delivery occurs independently of the cardiac cycle (i.e., throughout systole and diastole). Images courtesy of Prof. Piotr Musialek and Dr. Adam Mazurek

Intramyocardial injections were first reported in clinical trials in 2007 with autologous BM-MSCs in patients with previous MI and severe LV dysfunction. Improved regional wall thickening and perfusion scores were observed at the 3-month follow-up [26]. The beneficial effect of BM-MSC implantation seems to remain present throughout longer observation periods, as other studies show [27–30].

The combination of ADSCs’ direct implantation and creation of small channels using a medical laser through a left sided mini-thoracotomy was described by Konstanty-Kalandyk et al. [31, 32]. Excellent safety and feasibility results of a simultaneous harvest and implantation were provided. The Athena trial was also designed to investigate the efficacy of direct ADSC implantation. Initial results were promising for quality of life improvement at the 1-year follow-up, but the trial was prematurely terminated due to non-ADSC-related adverse events and subsequent prolonged enrollment time [33]. Efficacy results from large randomized placebo-controlled trials are still lacking; however, improvement in overall LV contractility and regional wall thickening combined with alleviation of symptoms has been reported throughout most of the studies. Currently, we are awaiting results from two large multicenter RCTs using direct intramyocardial injections of ADSCs [34, 35].

To conclude, most of the stem cell-based therapies were summarized in the systematic review from the Cochrane Database [36]. Based on the results from a total of 1010 participants from 21 randomized studies (with intramyocardial or intracoronary autologous adult stem/progenitor cell delivery) that reported long-term follow-up (> 12 months), a mortality rate of 4.8% (28/587) was observed in participants who received cell therapy compared with 15.4% (65/423) in those who received no cells. A meta-analysis showed that cell therapy reduced the risk of long-term mortality (RR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.25 to 0.58; participants = 1010; studies = 21; I2 = 0%). However, further larger studies may be needed to draw robust conclusions as most of the included studies were very small, leading to a risk of small-study bias and spuriously inflated effect sizes. Nevertheless, the observed long-term survival benefit should be considered promising, especially as it was observed irrespectively of the underlying diagnosis (IHD, HF secondary to IHD, refractory angina) and co-interventions, and included only results up to 14th Dec 2015.

Matrix scaffolds and bioengineered myocardial patches

The creation of bioengineered biomaterials made it possible to design delivery systems that provided a scaffold for stem cells. This drew attention to the potential of replacing damaged tissue with fabricated and personalized novel tissue [37]. Recent technological development enabled the implementation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into a bioengineered 3-dimensional (3D) microtissue (referred to as ‘cardiospheres’, ‘cardiac spheroids’, or ‘cardiac organoids’). The direct implantation of such bioengineered patches has been investigated in rodent and swine models with excellent results [38–40]. This technique offers a single, but probably highly important advantage over the previously discussed stem cell-based therapies, as it supplies the stem cells with a microenvironment that influences tissue growth and cell behavior [10].

Early trials with human participants were performed within the last decade and the first case report of a cellular patch applied to a human heart was described in 2015 by Menasche et al. [41]. The cell-loaded fibrin patch was developed using human embryonic stem cells (ESC), retrieved from Master Cell Bank, which were amplified and cardiac-committed. The procedure was performed in a 68-year old man through a median sternotomy with concomitant CABG to the non-infarcted area. With 6 more implantations in the ESCORT trial, all concomitant to conventional cardiac surgery, the researchers demonstrated feasibility of the procedure and overall improvement in HF symptoms and myocardial contractility [42].

Also another approach to combine stem cells with the matrix patch directly placed on the injured area of myocardium is currently being investigated (NCT04011059). The study is designed to assess neomyogenesis after the injection of Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs into the extracellular matrix placed on the epicardium during CABG in patients with previous MI.

Nevertheless, the issues of scalable manufacturing, to personalize the size of the patch, and patient-compatible 3D bioprinting, to avoid the need of immunosuppression, have not been resolved by clinical trials so far. However, the successful use of bioinks to create microfibrous scaffolds that can be engineered into human cardiac organoids was described by Zhang et al. in 2016 [43]. Shortly after, Noor et al. presented promising results for iPSCs, generated from the patient’s own omental stromal cells, combined with personalized bioinks created from fatty tissue extracted from the patient [44]. In this study, the bioengineered patch was designed to match the exact region of myocardial injury and to fit the blood vessel geometry to optimize the blood supply to the patch. This was established based on the computed tomography scans of volunteer patients, and prints were made as proof of concept. Although in vivo animal implantation experiments are still to be performed, this technique may make it possible to supply the patient with a fully personalized and biocompatible myocardial patch that can be implanted through minimally invasive cardiosurgical access in the future.

Other approaches to aid the blood supply to bioengineered patches included built-in vasculature and implantation with direct surgical anastomosis to the vessels [38, 45]. However, such techniques have not yet reached clinical trials.

Acellular materials

Acellular materials have also demonstrated preclinical therapeutic potential to promote angiogenesis and release of growth factors to improve restoration of key components of the extracellular matrix [46]. As cardiac surgeons already have experience with synthetic materials for structural purposes, such as GORE-TEX and other textile grafts, a thin mesothelial patch can easily be sewn on the epicardium. A bioinductive extracellular matrix (CorMatrix Cardiovascular Inc., United State) has already been tested in a porcine model and significant myocardial recovery was observed after epicardial repair [47].

Future perspectives

Other sources for stem cells are currently being investigated. In the study by Wang et al., a portion of the thymus, that is usually removed and discarded during neonatal cardiac surgery, was evaluated for the possibility of MSCs’ isolation and cardiac regenerative potential. The primary rationale of the study was that newborns undergoing cardiac surgery are at risk of developing end-stage HF over time. Collected MSCs were implanted in rat models with promising results with no need for additional scaffolds [48].

Moreover, the potential of both bioengineered and decellularized 3D neoscaffolds to create a full bioartificial heart is still being investigated. Initial reports show promising results, but future clinical strategies and applicability seem to be years ahead [49–52].

Nevertheless, a possibility of a few much simpler regenerative approaches has arisen, since the endogenous potential of cardiomyocytes has been further understood in fish, amphibians and neonatal mammals. Several translational and transcriptomic markers have been identified as responsible for the capability to repair cardiac damage. Therefore, direct delivery of selected microRNAs, to endow pro-proliferative activity, and cyclins, to reactivate the cell cycle, hold great potential for cardiac regeneration [53].

Conclusions

Although all of those techniques present several challenges, at least some have the potential to develop into a clinically available approach in the coming years. If successful, regenerative technologies have the capacity to re-shape therapeutic goals and to promote cardiac regeneration as an additional part of cardiac surgery. The number of potential treatment options is increasing, but so far robust evidence to support their efficacy and wide use varies from non-existent to only promising.