Introduction

Bloating is a prevalent condition and is common in daily clinical practice with a worldwide prevalence that ranges between 16% and 30% [1]. Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are classified according to Rome criteria and are the most common presentations in gastroenterology clinics around the globe, with dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) being more clinically relevant [2]. The prevalence of both vary globally with prevalence rates varying from 20% [3] to 40% [4], and both are frequently associated with bloating.

In clinical practice, patients with bloating as the predominant presentation are seen daily, and despite medications the sense of bloating persists in many instances and is described by patients as troublesome. IBS, functional dyspepsia, and chronic idiopathic constipation are recognised as the causes of bloating [5]. Previous reports showed improvement of bloating, dyspepsia, and abdominal pain after courses of different antibiotics as well as probiotics [3, 6], both focusing the bowel bacterial species that are altered among the patients (dysbiosis) and generally described as excessive growth of bacteria in the small intestine (SIBO) [7].

However, in daily clinical practice, particularly in resource-deficient communities, performing the breath tests and endoscope-dependent small bowel aspirate is challenging due to matters of availability, cost, sensitivity, false results, and the special preparations required [8, 9]. In addition, testing for functional abdominal bloating is not a necessity [10], and hence it may be justified to prescribe this category of patients a course of antibiotics/probiotics aiming at eliminating any infectious process and bring patients back to the eubiosis state, which will probably relieve their bloating sensation [3, 6]. This was the rationale behind this study.

Aim

We aimed to investigate the impact of cefixime antibiotic and probiotics on the bloating sensation among patients with functional abdominal bloating (FAB).

Material and methods

This was a prospective non-randomised open-label multicentre study, focusing on patients with bloating with or without abdominal distension as the leading manifestation. The patients were chosen from the outpatient clinics (OPD) of the participating centres. After an explanation of the concept, steps, benefits, and risks of the study, the patients were asked to sign an informed written consent form before being considered as potential candidates for the study.

Definitions

Bloating is defined in the current study as a sensation of trapped gas, abdominal pressure, and fullness [11], with application of the Rome IV diagnostic algorithm [12, 13]. We used a simple questionnaire with questions focusing on the presence or absence of bloating, severity of bloating, impact of bloating on the quality of life, and association with other manifestations (Supplementary File 1).

Distension is defined as a noticeable increase in abdominal girth [11].

Functional abdominal bloating is defined as a dominant feeling of abdominal fullness or bloating without sufficient criteria for diagnosis of another FGID [13, 14].

Dyspepsia is a complaint related to the upper bowel and is a combination of postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning that are severe enough to interfere with the usual activities and occur at least 3 days per week over the preceding 3 months with an onset of at least 6 months in advance [12, 13].

Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional bowel disorder related to the large bowel with recurrent abdominal pain, and it is defined in the current study following the Rome IV diagnostic algorithm [12, 13].

Resolution of bloating. In the current study, bloating was considered resolved if the sense of gases and any associated impairment in the quality of life ceased.

Severity of bloating. In the current study, bloating was graded subjectively as mild, moderate, or severe [15].

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients of any gender in whom bloating was the presenting manifestation were eligible to be included in the current study if they agreed upon participation and gave their signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

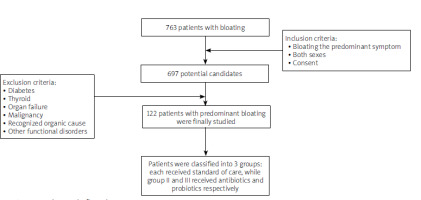

Patients with recognised causes of bloating other than FAB, either functional or organic, were excluded, including patients with IBS, functional dyspepsia, H. pylori infection, bowel infection, etc. Patients who had received antibiotics or any probiotic preparation in the preceding 2 weeks were ruled out. Patient with diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, chronic parenchymatous diseases, e.g. cirrhosis, and patients with malignancy were also excluded from the current study (Figure 1).

Management

All patients were subjected to the following:

Full history taking.

Thorough clinical examination with special attention to any obvious abdominal distension.

Laboratory assessment including the following: routine stool analysis, H. pylori stool antigen, faecal occult blood, CRP, ESR, CBC, FBS, glycated haemoglobin, and TSH.

Imaging – all patients were examined by abdominal ultrasonography. Further examinations were individualised, e.g. patients with suspected small bowel diverticulosis were examined by CT scan.

The aim of the diagnostic work up was to fulfil the diagnostic criteria of functional bloating according to the Rome IV algorithm and rule out possible organic causes as well as other functional bowel disorders.

Treatment: Patients with recognised causes of bloating detected by clinical assessment and reasonable investigation were treated according to the current practice guidelines. Patients of primary bloating were assigned into 3 groups: group I, treated by a combination of non-activated herbal charcoal (Eucarbon®) and silicone dioxide with dimethylpolysiloxane (Disflatyl) each 2 tablets 3 times a day [6, 16], described as the conventional treatment group; group II, treated by the same lines as in group I with the addition of cefixime 400 mg once daily for 6 days; and group III, treated by the same lines given to group I with the addition of a probiotic formulation harbouring the probiotic strain Lactobacillus helveticus candisis THE 401 concentrated at 5 or 10 billion per capsule (Lactibiane CND) for 2 weeks.

Patients were assessed after completing the treatment course by means of a symptom questionnaire (Supplementary File 1).

Sample size

The sample size was calculated for the pilot nature of the study assuming the prevalence of bloating to be 26.9% [17]. Aiming to detect an expected difference of 30% between the groups based on a 0.80 power to detect significant difference (p = 0.05, two-sided), 40 patients in each arm was seen as suitable for the the study.

Secondary endpoint

The safety of the used medications was viewed as the secondary end point of the current study.

Statistical analysis

Data collected throughout history, basic clinical examination, laboratory investigations, and outcome measures were coded, entered, and analysed using Microsoft Excel software. Data were then imported into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 20.0) software for analysis. Qualitative data are represented as number and percentage, and quantitative data are represented as mean ± SD. The chi-square test (χ2) was used to study comparisons and associations between 2 qualitative variables. The ANOVA (f) test is a test of significance used for comparison between the 3 groups’ quantitative variables, while the t-test was used for comparison between any 2 groups having quantitative variables with normal distribution. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study participants

During the study period 763 patients with bloating were reviewed in the OPDs of the participating centres. Among them 66 were unwilling to participate, and finally 697 were potential candidates for inclusion. After application of the exclusion criteria, 575 patients were finally excluded; out of them 177 patients had non-functional bloating or bloating associated with other functional disorders (n = 398) and were individually managed case by case according to the current practice guidelines, and 122 patients with predominant bloating were finally studied (Figure 1).

When the patients with predominant bloating were compared with patients with recognised probable causes of bloating, as shown in Table I, it is obvious that patients with non-FAB had significantly indigested food in their stool, bowel infections (Salmonella and H. pylori), and anatomical abnormalities (gall stones and small bowel diverticulosis) in comparison to patients with FAB. Three patients of the functional bloating group had silent gall stones and fulfilled the criteria of FAB. Notably, the patients recruited in the study are multi-ethnic including Arabs, Asians, Indians, and Africans.

Table I

Comparison between the functional bloating patients and the other bloating patients

Bloating group characteristics

The prevalence of FAB among the population of the current study was 15.98% (122/763). Patients of the FAB were divided into 3 groups and were managed as per the study protocol. Table II shows a baseline comparison between the 3 groups. Patients were comparable in their baseline characteristics. Most of the patients (58.1%) who presented with bloating were females. Among the functional bloating group, moderate intensity bloating was the most commonly reported sensation (43.4%), followed by severe bloating (38.6%), and mild bloating was reported among 18% of patients.

Table II

Comparison between the 3 groups before initiation of treatment

Bloating in the current study was associated with abdominal pain (mostly of moderate intensity and reported among 22.9% of patients across the 3 groups), and more than two-thirds of the patients (n = 83, 68%) had associated visible abdominal distension. Furthermore, bloating in the current study was associated with belching, changes in bowel habits, and nausea/vomiting, as shown in Table II, but without statistically significant differences among the 3 groups.

Response to treatment

All patients were followed for a period of 2 weeks. During the follow-up, assessment relied on the symptom questionnaire (Supplementary File 1). The sensation of bloating and its impact on the quality of life and the associated manifestations were compared among the 3 groups. All patients in the 3 groups reported subjective symptom improvement regarding bloating and the associated manifestations (Table III).

Table III

Post-treatment parameters among the 3 groups

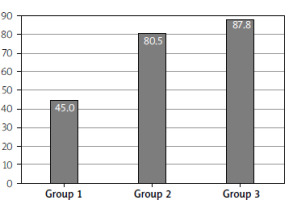

The frequency of improvement, as shown in Figure 2 and Table III, was significantly higher among patients who received cefixime and probiotics when compared to patients in whom the conventional therapy alone was prescribed (p = 0.005 and < 0.001, respectively). Furthermore, when groups II and III were compared, improvement in bloating and the associated manifestations were non-significantly higher in the probiotic group than in the cefixime group (p = 0.144). For the manifestations of nausea, vomiting, and bowel habit changes, all patients in the 3 groups reported improvement, and consequently all patients reported improvement in their quality of life. The conventional treatment seems to work sufficiently either alone or in combination with cefixime/probiotics for mild cases of bloating (p = 0.326), contrary to moderate and severe bloating in which the addition of cefixime/probiotics seems essential to achieve significant improvement (Table III). The manifestations related to the sense of gases (belching) and abdominal pain showed marked improvement after treatment, although the improvement was not statistically significant between the 3 groups, as shown in Table III. The objective feeling of abdominal distention was significantly different among the 3 groups, with higher improvement in the probiotic-treated group (p < 0.001).

Discussion

An important question arises here: why was bloating specifically focused on in the current study? The answer can be inferred not only from the clinical studies that link bloating with poor quality of life [17], and its association with severe abdominal pain particularly among younger patients [15], but also from the practice viewpoint; in our daily clinical practice bloating is the leading presenting complaint in a reasonable number of patients, and this was emphasised by the results of the current study (Figure 1). Furthermore, bloating rather than distension was focused in the current study (although they usually co-exist, and also may occur independently [11]) because the sensation is usually the drive that forces the patient to the clinic and impacts his/her quality of life more [18]. This is obvious from the results of the current study; the primary end point of this study was bloating as the leading manifestation. Furthermore, the sense of gas trapped in the bowel (bloating) is sometimes associated with belching and passing flatus, which further bother the patient [5], although it is not necessarily associated [19], and this was noticed through the associated manifestations reported in the current study (Table II).

We believe that the current study delivers some important messages. First, it is one of the few studies focusing on patients with bloating, although bloating is a prevalent condition [17], and it had an impact on the quality of life [20] with an additional cost on the health care systems among adults [21], children [2, 22], and even infants [23]. There are few studies focusing on FAB in the literature because bloating in many instances is associated other conditions, e.g. IBS, dyspepsia, constipation, etc. The frequency of functional bloating among patients presented with bloating in the current study is 15.98% (122/763), a figure higher than the 6.2% frequency reported by Ryu et al. [17], and similar to the 16% rate reported by Sandler et al. [24], and the difference may be related to the subjective nature of the condition and the multicentre, multi-ethnic nature of the populations recruited in the current study.

In the current study bloating was common among females, and most of the encountered cases were of moderate intensity (58.1% and 43.4%, respectively). This is in agreement with Gardiner et al. [21], who reported bloating among a cohort of 612 cases with FIGDs, and they reported females as 78% of cases; however, mild bloating was the commonest severity (37.8%).

Cefixime is a cephalosporin with broad spectrum activity [25]. It was used to treat GIT disorders as early as in the 1980s [26], and its choice in the current study relied on many aspects: it is readily available, at an affordable price, requires only single daily use, and has short duration of intake, i.e. for 6 days. These fulfil the ideal characteristics proposed for an antibiotic in the treatment of bowel infection, which would ideally entail a broad-spectrum activity against gram-positive and -negative organisms with a minimal side-effect profile and low resistance [3]. Although cefixime per se was not tried before for treatment of FAB or SIBO, the idea to use broad spectrum antibiotics in this issue was focused on in a recent publication by Richard et al., who used quinolones and azoles either alone or sequentially one after the other, and both regimens were found to be effective in the management of SIBO [27]. The cumulative evidence in the literature favours the use of rifaximin [28] and neomycin [29], mainly due to its broad-spectrum local activity in the bowel and minimal systemic side effects [3]. However, rifaximin is not readily available and is costly in comparison to cefixime. Also, it is used for 2 weeks. Furthermore, rifaximin is not indicated for treatment of FAB or SIBO in some countries [27]. On the other hand, neomycin had the potential of oto-renal toxicity with potential development of bacterial resistance [30]. The current study showed for the first time a role for cefixime in a single daily dose of 400 mg in the treatment of FAB, and this may point to an underlying dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of bloating. However, the absence of 100% improvement with both cefixime and the probiotics rule out dysbiosis as the sole underlying pathophysiological mechanism for the occurrence of FAB. The use of systemically active antibiotics like cefixime is theoretically associated with possible systemic side effects that have not been reported in the current study.

Probiotics have been tried in the treatment of bloating by modifying the composition of gut flora, and consequently gas production [31]. Many strains have been tried with overall promising results [30–32]. The superiority of probiotics over the antibiotics is related to colonisation of the bowel with beneficial bacteria, in comparison to modulation of the bacterial species; this is evident in the current study where the improvements in the probiotic-treated group were non-significantly higher than the antibiotic (cefixime) group, although both had a good safety profile. The degree of improvement in severe bloating, distension, belching, and abdominal pain was greater in the probiotic group when compared with the other 2 groups. Similar observations were reported earlier by many authors [30–33], although there were no agreements on the strains, doses, and duration of probiotic supplementations used.

The current study had its limitations. First is the small number of patients recruited, and this may be related to the pilot nature of the study. Second is the lack of stool culture to define faecal microbiota changes over the duration of therapy. Third is the lack of long-term follow-up after discontinuation of therapy to determine the durability of the effects reported. Forth is the inability to explain the improvement in the symptoms among the groups solely on the background of eubiosis. Fifth, abdominal bloating is a subjective sensation, and this variable might affect the prevalence rates reported in the literature, especially when the cohort of patients are multi-ethnic with different cultural and educational backgrounds, as described in the current study. Future studies with larger numbers of participants followed up for longer duration will overcome the limitations of the current study.

Conclusions

The frequency of functional abdominal bloating in the current study is 15.98%. Patients with functional abdominal bloating, focused on in the current study, showed improvements with the conventional therapy, cefixime antibiotic, and probiotics with good safety profile. However, the probiotic-treated group showed non-significantly greater improvement than did the cefixime-treated group, and both showed significantly greater improvement than conventional therapy.