Introduction

Quality of life is “the functional effect of a disease and its treatment, subjectively or objectively perceived by the patient.” Although this concept has accompanied humans since antiquity, it was first introduced in medicine in 1990 by Schipper, who distinguished four basic dimensions of the quality of life: physical, mental, social and economic conditions. The physical condition is mainly related to mobility, self-service ability, physical activity and life energy. The mental state concerns the emotional cognitive sphere. The social situation relates to the performed social roles and functions, interpersonal contacts and gaining the support of relatives [1]. Ebrahim, on the other hand, states that the quality of life is determined by the state of health and life expectancy, as well as modified by physical disability, functional limitations, the way they are perceived and the possibilities of social activity. It depends on the type of disease, the applied treatment and long-term monitoring of the therapeutic procedure [2]. Researching the quality of life in medical terms means identifying the problems resulting from the disease and the treatment used, regarding human activity in the physical, mental and social sense, and describing the patient’s views on health and their subjective well-being.

The term “successful aging” has been used in the gerontological literature for several decades. It was first used by Robert J. Havighurst and Ruth Albrecht [3,4]. They believed that it was closely related to earlier periods of life (childhood, youth and adulthood), and people who felt they had lived happily and were satisfied with their lives aged successfully. Positive aging is also defined as an attitude towards one’s own old age and its acceptance. Manifestations of this attitude include taking up and continuing social activity in old age, for example participation in activities at Universities of the Third Age (UTA) [5]. Ann Bowling attempted to organize the definition of successful aging and listed the categories that, in her opinion, should be included in the definition of successful aging, i.e. longevity, mental and physical health, cognitive performance and social functioning, coping, favorable life circumstances, life satisfaction [4,6].

The quality of aging of older people has become the subject of many studies in recent years [7-10]. The growing interest in the issues of old age is related to the progressive aging of societies and the increasing share of older people in the general structure of the population. At the end of 2020, the number of people aged 60 and over in Poland amounted to 9.8 million and increased by 1.0% compared to the previous year. According to the forecast of the Central Statistical Office, the number of seniors in Poland in 2030 is expected to increase to 10.8 million, and in 2050 even to 13.7 million, which will constitute about 40% of the entire population of Poland [11]. This means that in Polish society we are dealing with demographic old age. So, it is important that seniors age successfully and their quality of life is very good.

UTA, established in Poland since 1975, are the most widespread, institutional form of education for seniors to improve the quality of life of older people. UTA contribute to satisfying the psychosocial and health needs of their students [12]. In their youth, seniors often had to give up education for economic, life or other random reasons. As a result, unmet needs remain in their lives, such as the need for self-education, establishing new social contacts, being socially, physically and culturally active. Attending UTA allows them to meet the needs mentioned above, as well as improve the quality of their lives. Other equally important goals of UTA are, for example, activation and integration of elderly people and their inclusion in the public and civic life of local communities. The specific goals of UTA are: inspiring older people to various forms of physical activity, shaping a healthy lifestyle, raising knowledge about the importance of exercise in everyday life and stimulating rational planning, organizing and spending free time. Numerous UTA undertake and successfully implement national and international cooperation with other senior organizations, in which it is extremely valuable, for example, the exchange of experiences. It can be said that the activity of UTA aims at the broad inclusion of older people in the multidimensional process of education, activation and integration, giving life meaning in the context of civilization, social and cultural changes. Inspiring seniors to various forms of mental and physical activity, including social, cultural and pro-health, is aimed at counteracting social exclusion and manifestations of discrimination [13].

The results of research conducted by the Central Statistical Office on households of older people in Poland showed that people with secondary and higher education and still gaining knowledge (including UTA students) are distinguished by better health, and greater physical and intellectual fitness compared to with their peers who do not conduct this type of activity [12].

Aim of the work

The aim of the study was to assess the quality of aging of seniors living in the cities of the Silesian conurbation (Poland).

Material and methods

436 seniors living in cities located in the Silesian conurbation were surveyed, including 340 (77.98%) attending the UTA classes and 96 (22.02%) not attending the above-mentioned classes. Among them there were 362 (83%) women and 74 (17%) men. The research tool was the original questionnaire supplemented with the standardized Successful Aging Index (SAI) questionnaire.

The author’s questionnaire consisted of a part containing socio-demographic questions, as well as a part regarding the examined problem. It included questions about: participation in the UTA activities, subjective assessment of changes occurring in life after retirement, ways of spending free time, reasons for taking up physical activity, everyday activities, meetings with family and friends, regular visits to the doctor, and the use of stimulants such as cigarettes and alcohol.

SAI is used to assess successful aging. It consists of 12 questions, with answers scored 1 to 5 respectively. The domains of the questionnaire in which the assessment is made, as well as the individual questions included in the result of a given domain, are as follows: health/well-being (questions no.: 1, 2, 10, 11, 12), sense of security (questions no.: 7, 8, 9), retrospective factors (questions no.: 3, 4, 5, 6). The proposed answers are scored from 1 to 5. The average of the question points assigned to a given domain (health/well-being, sense of security, retrospective factors) constitutes its result, and the sum of the domains is the indicator of successful aging – SAI [14].

The inclusion criteria for the study were: voluntary consent and the ability to complete the questionnaire independently, age 60 and over, and living in the cities of the Silesian conurbation.

Completing the survey and the SAI questionnaire was completely anonymous. After they were completed by the respondents, they were placed in white, unmarked envelopes, and the envelopes were collected in one secured place. Opening envelopes with completed questionnaires only when entering the results into the database made it impossible to identify the people participating in the study.

In order to test the significance of differences between the analyzed subgroups, the Chi2 test was used for qualitative data and the U Mann-Whitney test for quantitative variables, due to lack of normal distribution in the data. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All analyses were performed in Statistica 13.1 software.

Results

The characteristics of the seniors of the study group, including the subjective assessment of their health, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the seniors in the study group, including the subjective assessment of their health

Seniors participating in the UTA classes most often assessed their health condition as good (175; 51.47%), and those who did not participate – as average (44; 45.83%). Observed differences were statistically significant (p=0.02).

The characteristics of the seniors in the study group, including the subjective assessment of changes in their lives after retirement, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Characteristics of the seniors in the study group, including the subjective assessment changes in their lives after retirement

The greatest number of seniors assessed retirement as a change for the better in their lives, both in the group of seniors participating in the UTA classes (177; 52.06%) and in the group not participating in the classes mentioned above (35; 36.46%) Observed differences were statistically significant (p=0.03).

The characteristics of the seniors in the study group, taking into account the way they spend their free time, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Characteristics of the seniors in the study group, taking into account the way they spend their free time

| Way to spend free time | Seniors participating in the UTA classes | Seniors not participating in the UTA classes | Chi2 test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | df | p | |

| Active | 249 | 73.24 | 39 | 40.62 | 32.65 | 1 | <0.001* |

| Passive | 91 | 27.76 | 57 | 59.38 | |||

| Sum | 340 | 100 | 96 | 100 | - | ||

About two-thirds of the surveyed seniors participating in the UTA classes (249; 73.24%) declared an active way of spending their free time, while in the group of seniors not participating in these activities, more of them declared a passive way of spending their free time (57; 59.38%). Observed differences were statistically significant (p<0.001).

The characteristics of the seniors in the study group, taking into account the most common reasons for undertaking physical activity in their free time, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4

Characteristics of the seniors in the study group, taking into account the most common reasons for taking up physical activity

All surveyed seniors most often undertook physical activity to improve overall health (in turn: participating in the UTA classes – 122; 35.89%; not participating in the UTA classes – 26; 27.08%).

The characteristics of the study group’s seniors, taking into account their daily activities, are presented in Table 5.

Table 5

Characteristics of the seniors in the study group, taking into account their everyday life activities

The vast majority of the surveyed seniors, also those participating in the UTA classes, were independent in performing everyday activities (successively: 292; 85.88% and 60; 62.5%), regularly met their family and friends (successively: 330; 97.06% and 80; 83.33%) and were systematically examined (successively: 305; 89.7% and 84; 87.5%). The Chi2 test showed a statistically significant difference between seniors participating and not attending the UTA classes (p<0.001) in terms of independently performing everyday activities.

The characteristics of the seniors in the study group, with regard to attending the cinema/theater or museum, are presented in Table 6.

Table 6

Characteristics of the seniors in the study group, with regard to attending the cinema/theater or museum

Most of the surveyed seniors attended the cinema/theater or museum several times a year, regardless of their participation in the UTA classes (consecutively: participating in the UTA classes – 204; 60%; not participating in the UTA classes – 38; 39.54%). Observed differences were statistically significant (p<0.001).

The characteristics of the seniors in the study group, taking into account the use of stimulants, are presented in Table 7.

Table 7

Characteristics of the seniors in the study group, taking into account the use of stimulants

Over half of the seniors, also those participating in the UTA classes, consumed alcohol (successively: 193; 56.76% and 50; 52.08%), and over one third used tobacco in the past (successively: 127; 37.35% and 33; 34.37%).

Table 8 presents the results of the individual homes and successful aging rate of the studied group of seniors according to the SAI scale.

Table 8

SAI scale – the individual home scores and successful aging rate of the studied group of seniors

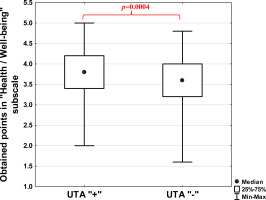

The successful aging rate in the group of seniors participating in the UTA classes was slightly higher 11.75 (Q1:10.73; Q3: 12.52) than in the group of seniors not participating in the classes 11.43 (Q1:10.37; Q3: 12.78). The highest score was obtained in both groups in the “sense of security” domain, but a statistically significant difference (U Mann-Whitney: Z=3.54; p=0.0004) between the points obtained by the study groups was shown only in the “health/well-being” subscale, as shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

The classes conducted at UTA are a very popular form of activation of the elderly. One of the main goals of these classes is to improve the quality of life of seniors [12]. Therefore, it was assumed that the quality of life of seniors belonging to the group of UTA students would be greater than that of seniors who were not students. Our own research showed that the SAI, which describes the quality of successful aging, was only slightly higher in the group of UTA students (11.75) compared to the group of seniors not attending the above-mentioned classes (11.43). However, the highest score was obtained in both groups in the “sense of security” domain, but a statistically significant difference (p=0.0004) between the points obtained by the study groups was shown only in the “Health/Well-being” subscale. Seniors who participated in the UTA classes, assessed their health better compared to seniors who did not participate in them and the observed differences were statistically significant (p=0.02).

As Burshtein et al. [15] pointed out, the retirement process is an individualized endeavor influenced by personal values and the surrounding environment. It is divided into three main stages: preparing for retirement, transitioning to retirement, and adjusting to retirement. The ability to successfully implement retirement plans is directly related to retirement satisfaction [15]. Honarvar et al. [16] in their research showed that satisfaction with retirement is related to the assessment of the quality of life and life satisfaction. In their own research, the moment of retirement was assessed by seniors as a change for the better in their lives, both in the group of seniors participating in the UTA classes and in the group of seniors not participating in them. This was probably related to the fact that the study group included people living only in cities that statistically have a better quality of life than people living in the countryside [17]. However, Seń et al. examined the quality of life of the elderly, both in the city and in the countryside, and used the scales and the World Health Organization Quality of Life – BREFF (WHOQOL-BREFF). In their research, rural residents obtained higher results in most domains constituting the assessment of the quality of life [18]. In the study by Grabaccio et al. [19], older people living in rural areas had good quality of life and health. Similar results were obtained by Wu et al. [20], who described a better quality of life among people living in newly established urban districts in China, but retaining rural habits and lifestyle. In light of the above reports, it is planned to extend the conducted research to the group of seniors living in rural areas in the Silesian conurbation and to compare the results in both groups.

In their analysis of the problems of an aging society, Lejzerowicz-Zajączkowska et al. [21] stated that physical activity had a significant impact on increasing independence, and thus improved the quality of life of the elderly. In this research, almost two-thirds of the surveyed seniors participating in the UTA classes declared an active way of spending their free time, while in the group of seniors not participating in these activities, more seniors declared a passive way of spending their free time, and it was statistically significant (p<0.001). The UTA students were more often physically active, probably because they had the opportunity to take advantage of the physical activities organized by UTA to which they belonged, and because they managed their free time more efficiently thanks to the knowledge acquired during the above-mentioned classes [12]. In this research, seniors most often undertook physical activity to improve their health in general. Baj-Korpak et al. [22] stated that the most common motivation for taking up physical activity by the seniors they examined was the desire to improve physical fitness (20%). In their work on physical activity and mental health of older people, Hemmeter et al. [23] noted that physical activity can prevent depression and dementia. Other authors also obtained similar results [24-26].

According to the data from the Central Statistical Office, every second person aged 65 and over has limitations in performing domestic activities due to health problems [27]. In our own research, most seniors were independent in carrying out everyday activities and regularly met with family and friends. There was shown a statistically significant difference between seniors participating and not attending the UTA classes (p<0.001) in above-mentioned everyday activities. Baj-Korpak et al. [22], in turn, observed that regular meetings with family and friends among seniors were in third place among the most common forms of spending free time they surveyed (20%). Attending the UTA classes can prevent seniors from being socially excluded and provide an opportunity to meet frequently with people of a similar age to them [12]. Wróblewska et al. [28] in their research showed that for more than half of the respondents, the most common reason for participating in the UTA activities was maintaining relationships with people from the same age group.

Most of the surveyed seniors attended the cinema/theater or museum several times a year, also regardless of their participation in the UTA classes. Obtaining such a result was probably also related to the fact that all the surveyed seniors lived in cities where the number and variety of cultural centers is large, and access to them is easy. There is a positive trend worldwide regarding the employment of older people in museums or other cultural centers as guides or service staff to prevent social exclusion of such people.

In this research, seniors were asked about the use of stimulants. More than half of them, also those participating in the UTA classes, consumed alcohol and over one third used tobacco in the past. Both alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking are risk factors for many diseases, including cardiovascular diseases and cancer [29-31]. Bartoszek et al. [32] observed that almost 30% of the seniors surveyed by them had contact with tobacco. They also showed that as many as 83.6% of the seniors drank alcohol, although it was noted that only occasionally.

Mihailovic et al. [33] showed that the prevalence of alcohol consumption among people over 55 years of age in Serbia and Hungary was 41.5% and 62.5%, respectively. In both countries, alcohol was consumed more often by men than women. However, in Poland, according to the analyses of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), men consumed 18.4 liters of pure alcohol per year, and women - 5.6 liters [34]. In turn, when it comes to smoking, there are many reports in the literature regarding the prevalence of smoking among young or middle-aged people, but not seniors [35-37]. This may be due to the fact that older people usually do not smoke or smoked in the past and quit, which was also shown by our own research.

As indicated by the results of the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS) elderly people often underwent basic preventive examinations [27]. In this research, the vast majority of seniors also systematically went to medical appointments and were examined regularly, regardless of attending the UTA classes. Such a result was probably obtained because all the surveyed seniors lived in cities where the number of medical facilities and actively working medics is large, therefore access to medical services is facilitated.

Conclusions

The quality of aging of the surveyed seniors living in the cities of the Silesian conurbation was good, while the self-assessment of their own health was better in the group of the UTA students compared to the non-participants.

Attending the UTA classes mobilized the surveyed seniors to spend their free time actively, but the most common motives for undertaking physical activity in both groups were similar.

The surveyed seniors of the Silesian conurbation, regardless of their participation in the UTA classes, actively participated in social and cultural life, were regularly examined, but unfortunately also used stimulants.