INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a major problem of our time, defined as a worldwide disease that affects men and women of all ages. The prevalence of asthma has been steadily increasing worldwide since the second half of the 20th century [1, 2]. It is characterized by lifelong chronic airway inflammation, cough, wheezing, wheezing, or chest tightness [3–6]. Due to exacerbations and severity of physiological manifestations, the patient’s life is largely affected.

Considering the severity and recurrence of symptoms, asthma can be classified as: mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent asthma. Severe persistent asthma is a condition in which symptoms occur almost every day, nocturnal symptoms are more frequent, and pulmonary function tests show an forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) lower than 60.00%, with a peak expiratory flow (PEF) change of more than 30.00% from morning to afternoon [7].

Of the entire population worldwide, severe asthma affects approximately 10.00%. The exacerbation of this type of asthma is acute, severe and may not respond to usual medical treatment. It is characterised by increased breathing and shortness of breath, in which it is difficult to hold a conversation [8, 9]. Factors of genetic and environmental origin play an important role in the onset of severe asthma, but severe asthma can develop during or immediately at the onset of respiratory disease. Two age-based phenotypes of severe asthma are best known – early-onset and late-onset. Early severe asthma is related to associated allergic diseases, while late-onset asthma is more symptomatic with marked eosinophilia and is characterized by a greater number of fatal cases [10].

According to current GINA guidelines, severe asthma does not achieve adequate control when treated with control medications via high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)-long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) (reliever medications) and antileukotrienes as additional control medications with limited indication [7, 11, 12]. Repeated cycles of oral corticosteroids (OCS) prescribed to patients increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVDs) such as osteoporosis, cardiovascular problems or metabolic disorders [13]. Many doctors recommend patients with asthma an active lifestyle, including the inclusion of sports activities in the patient’s daily routine that reduce cardiovascular risk. Studies have shown a reduction in asthma inflammation with moderate-intensity aerobic exercise [14, 15]. However, there are currently biological therapy options for patients with severe asthma such as injectable asthma medications (omalizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab, and dupilumab) which target different molecules and help patients who still have problems even though they are using other inhalers [16]. The financial cost of treating patients with severe asthma exceeds the cost of treating tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Health insurers in developed countries may spend approximately 1.00–2.00% of their budget on asthma management [17]. However, the cost of biological treatment per patient is around 650–1200 € per month in Slovakia [18].

Asthma is influenced by many factors – patient age, gender, residence, use of tobacco products, occupation, lifestyle, and others. It also interferes with the patient’s family and cultural and social life, where it largely affects the patient’s functioning [19]. Poorer asthma control is also associated with poorer sleep and earlier awakening of patients, as well as overall sleep problems. A relatively large number of patients report sleep problems that they do not attribute to comorbidities or poor asthma control [20]. Most patients are unable to perform normal or somewhat strenuous activities because of shortness of breath, chest pressure or coughing. Patients often have unpredictable exacerbations (asthma attacks or severe flare-ups). Through OCS control, patients are often exposed to the side effects of medications – obesity, diabetes, osteoporosis, fragility fractures, cataracts, hypertension, adrenal suppression, and last but not least, depression and anxiety, which are often difficult for the patient to manage [7].

Many studies have pointed to high levels of anxiety associated with emotional distress, which correlate closely with diagnosed asthma [21]. It has also been confirmed that patients with severe asthma cope less well with emotional situations, are more sensitive to pain, have difficulty fitting in and feel inferior [22]. The symptoms have a significant impact on levels of work performance, cultural enjoyment, social interaction or time spent with family. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to subjective experiences of people who understand the connection between medical history and social and psychological factors in their lives.

AIM

The aim of this study is to highlight the severity of severe asthma, which has a demonstrable impact on patients’ daily lives.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was conducted in a private immuno-allergology outpatient clinic in Eastern Slovakia in the time span between February 2023 and November 2023. The study sample consisted of 500 patients (250 females; 250 males) aged 18–81 years, who were diagnosed with asthma. It consisted of the measurement of anthropometric parameters selected by us (body height, body weight) from which body mass index (BMI) was then calculated using the formula BMI = (kg)/height2 (m2). Patients were examined by a physician and asked about the regularity of symptoms, exacerbations, worsening of health status, recurrence of seizures, etc. We then performed spirometric examination where we focused on FEV1 and classified patients into mild, moderate and severe asthma groups, focusing only on patients diagnosed with severe asthma (FEV1 ≤ 60.00%). At the same time, we conducted a qualitative study with a non-standardized questionnaire in which patients were asked individual questions regarding the impact of asthma on their social life.

RESULTS

In our research, we looked at the socio-cultural life of the patients and to what extent it is affected by severe asthma. In particular, we were interested in normal daily activities in which patients might experience exhaustion, lack of energy or psychological burden.

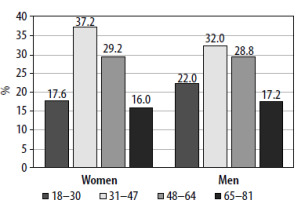

The most represented age group was that of 31–47 years, which is 37.20% in the female population and 32.00% in the male population (Figure 1). The least represented group was the 65–81 age group, which was expressed as 16.00% in the women’s population and 17.20% in the men’s population.

Considering the side effects of OCS as a standard control, we also investigated the BMI of patients at risk of possible obesity. The minimum and maximum body height in the female and male population for each age category is shown in Table 1. In the female population, the minimum body height ranged from 147.00 to 158.00 cm and the maximum from 172.00 to 180.00 cm. In the male population, the minimum body height was 158.00–168.00 cm and the maximum body height was 182.00–200.00 cm.

Table 1

Body height of patients

[i] Age cat. – age category, N – number of patients, Min. – minimum, Max. – maximum, SD – standard deviation, SEM – standard error of the mean, V – coefficient of variation, ns – statistically non-significant difference, **statistically significant difference, ***statistically highly significant difference.

Body weight was reported in kilograms and is recorded in Table 2, separately for the female and male population at each age. The minimum body weight for the female population ranged from 47.00 to 53.00 kg, and the maximum body weight ranged from 102.00 to 113.00 kg for each age category. The minimum body weight for the male population ranged from 57.00 to 64.00 kg, the maximum body weight ranged from 100.00 to 115.00 kg for each age category.

Table 2

Body weight of patients

[i] Age cat. – age category, N – number of patients, Min. – minimum, Max. – maximum, SD – standard deviation, SEM – standard error of the mean, V – coefficient of variation, ns – statistically non-significant difference, **statistically significant difference, ***statistically highly significant difference.

QUESTION 1. TO WHAT EXTENT DOES YOUR ILLNESS INTERFERE WITH YOUR FAMILY LIFE?

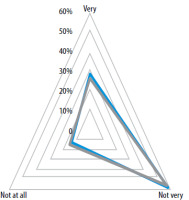

In our research, we found that for the vast majority of respondents in both male and female populations, the disease does not affect their family life very much. This was 58.80% for females and 58.00% for males. The second most frequent response was that bronchial asthma was very bothersome to their family life – females (28.80%), males (26.40%) (Figure 2).

QUESTION 2. DOES YOUR DISEASE LIMIT YOU IN STRENUOUS ACTIVITIES?

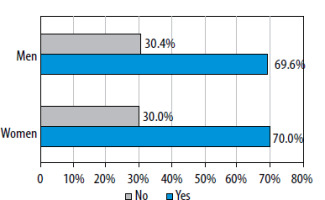

As can be seen in Figure 3, bronchial asthma limits patients in performing strenuous activities. This accounts for 70.00% of the female respondents and 69.60% of the male respondents.

QUESTION 3. DOES YOUR ILLNESS BOTHER YOU DURING SOCIAL ACTIVITIES, VISITS OR HOBBIES?

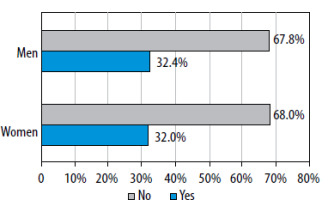

According to the results reported below (Figure 4), the disease does not bother most patients during social activities, visits or hobbies. In the female population, 32.00% of the respondents reported that the disease bothers them in social activities. Among male respondents, this accounted for 32.00%.

QUESTION 4. DOES THIS DISEASE INTERFERE WITH YOUR MENTAL HEALTH OR DO YOU EXPERIENCE A LACK OF ENERGY RELATED TO THE DISEASE?

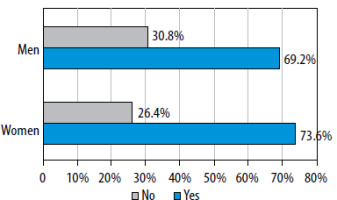

According to the collected data, we can see that in 73.60% of the female population and 69.20% of the male population, this disease interferes with the psychological health of the patients who may feel lack of energy related to this disease (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Various clinical and pathophysiological aspects of asthma have been extensively studied, but the important link between asthma and physical activity remains underappreciated and understudied. Severe asthma has an adverse effect on physical activity, but equally, physical inactivity may lead to worse asthma outcomes. For this reason, we decided to explore the area of socio-cultural perspectives of asthma patients.

The vast majority of patients (70.00% of females and 69.60% of males) expressed that this disease limits them in performing strenuous activities such as sports, heavy manual work or other strenuous physical activity. Our results are supported by the research of Panagiotou et al., in which they point out that a recent systematic review of all available studies using a control group identified 11 studies (asthma sample = 32,606) that reported less physical activity in asthma, and 6 studies (asthma sample = 7,824) that reported no difference, leading to the conclusion that people with asthma perform less activities compared to the control group [23]. Restriction of physical activity can also result in adverse effects on an individual’s mental health. Patients were asked if the disease interferes with their mental health or if they experience a lack of energy related to the disease. 73.60% of the female population and 69.20% of the male population agreed that asthma adversely affects their mental health and they feel lack of energy. The research conducted by Stanescu et al. highlights the fact that psychological and health factors significantly increase the burden of living with asthma, but also that the prevalence of psychological dysfunction and health risk factors appear to be common in people with asthma. In addition, the complex nature of patients with chronic diseases such as asthma, with interacting factors, contributes to the negative experience of living with asthma [24].

CONCLUSIONS

It should be noted that the problem of severe asthma is stagnating and despite advances in medical treatment, there is no significant improvement in patients’ quality of life. The impact of the disease does not only limit patients through symptoms, but also causes a significant emotional, financial and functional burden, leading to a deterioration in the quality of social life. As well as identifying the levels of burden of severe asthma, the patient’s perspective and quality of life with the condition must also be considered. An important point to increase public knowledge and awareness of severe asthma would be to outline strategies to help asthma patients experience greater comfort in daily life.