Introduction

Fatty liver disease has steadily emerged as a significant public health concern in the 21st century, mirroring the global rise in obesity and metabolic syndrome [1]. However, significant changes in the disease nomenclature, definitions and diagnostics were made through the years, leading to some confusion on the subject.

Probably the most commonly used term, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) encapsulates a spectrum of disease stages, from simple hepatic steatosis to the more severe nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, and even cirrhosis [2]. Notably, this disease is no longer confined to the realm of hepatology, extending its impact to cardiovascular health.

Increasingly, research suggests that NAFLD is intricately linked to cardiovascular diseases (CVD), which are currently the leading cause of mortality worldwide [3]. In this context, NAFLD has been identified as a potential independent risk factor for CVD, adding further complexity to managing cardiovascular health [4]. This connection potentially stems from the shared risk factors between NAFLD and CVD, such as insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity [5].

However, NAFLD’s precise role and mechanisms as a cardiovascular risk factor remain areas of ongoing exploration and debate, underscoring the need for a comprehensive review. This article aims to synthesize existing literature on the subject, delineating the current understanding of the pathophysiological links between NAFLD and CVD and illuminating the potential implications for clinical practice. It also seeks to identify gaps in current knowledge and to provide direction for future research.

Changes in the disease names and definitions

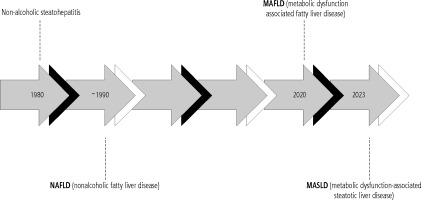

Harmonized strategies worldwide for disease naming and definition are of utmost importance for enhancing disease understanding, promoting policy reforms, pinpointing those at risk, easing the diagnostic process, and ensuring access to medical care. Overweight and obesity-related hepatic steatosis, hepatocyte injury, liver inflammation and fibrosis were first formally recognized by the term “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis” in 1980 [6].

Following this, the term “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease” came into use to represent the histological range from steatosis to steatohepatitis, including its subtypes nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and NASH. The histological categorization was further detailed through various scoring systems, classifying levels of steatosis, disease activity, and fibrosis [7, 8]. The abbreviation NAFLD has been widely accepted for many years. However, it has long been understood that the term “nonalcoholic” does not precisely depict the disease’s etiology, and recently the term “fatty” started to be perceived as stigmatizing by certain individuals. It was also noted that alcohol consumption in some patients with NAFLD-specific phenotype exceeded the relatively strict thresholds to define the diseases’ nonalcoholic nature [9].

In 2020, a consensus was proposed with a new nomenclature [10]. The term “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver diseases” (MAFLD) was introduced. However, a wave of criticism has emerged, not only about the acronym and definition itself but also about the choice of panelists responsible for the consensus [11].

In 2023, the name was again changed in a multisociety Delphi consensus statement [12]. This time, a consensus was made under the auspices of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) in collaboration with the Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado (ALEH) with the engagement of academic professionals from around the world. The name chosen to replace NAFLD was metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) (Fig. 1). For the first time, the disease is now defined not as a lack of other steatosis causes but by other criteria. Currently, MASLD should be diagnosed in adults with steatosis and any one of the following cardiometabolic criteria:

body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 or waist circumference > 94 cm (male) and 80 cm (female) or ethnicity adjusted,

fasting serum glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/l (100 mg/dl) or 2-hour post-load glucose levels ≥ 7.8 mmol/l (≥ 140 mg/dl) or HbA1c ≥ 5.7% (39 mmol/l) or type 2 diabetes or treatment for type 2 diabetes,

blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or specific antihypertensive drug treatment,

plasma triglycerides ≥ 1.70 mmol/l (150 mg/dl) or lipid-lowering treatment,

plasma HDL-cholesterol ≤ 1.0 mmol/l (40 mg/dl) (male) and ≤ 1.3 mmol/l (50 mg/dl) (female) or lipidlowering treatment [7].

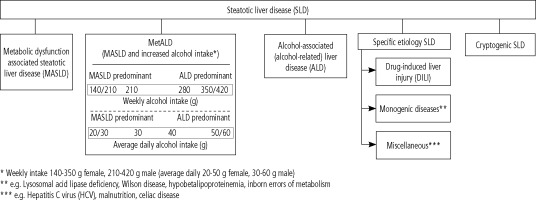

Additionally, the term MetALD was selected for MASLD in those who consume greater amounts of alcohol. The current steatotic liver disease sub-classification according to the multi-society Delphi consensus statement is shown in Figure 2 [12].

Fig. 2

Steatotic liver disease sub-classification according to multi-society Delphi consensus statement. Modified from ref. [12]

In the current review, the novel term MASLD will be encouraged; however, when referring to older studies, especially epidemiological ones, the terms NAFLD and MAFLD will be used, as they were in the cited manuscript, due to certain differences in diagnostic criteria, which could lead to potential bias.

Epidemiology of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD in cardiovascular patients

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is increasingly recognized as a significant global health concern. It is the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting nearly 25% of the global population [13]. The prevalence of NAFLD varies substantially among different geographic regions, primarily driven by diverse lifestyle habits and genetic factors.

In Western countries, the prevalence of NAFLD is estimated to be between 20% and 30% in the general population and up to 70-90% in certain high-risk populations, such as individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes [14]. The disease prevalence in Asian countries is also rising, partly due to the rapid economic growth, urbanization, and adoption of a Westernized lifestyle, with estimated rates ranging from 15% to 30% [15, 16].

Diverse demographic factors are associated with the risk of developing NAFLD. Among these, age and gender play a significant role. NAFLD is more prevalent among middle-aged and elderly individuals than younger age groups, likely due to the cumulative effect of metabolic risk factors over time [17]. Gender also influences NAFLD risk, with men showing a higher prevalence than women until the postmenopausal period, when the gender difference appears to equalize [18].

As cardiometabolic factors are the main contributors to MASLD, many studies focus on the prevalence of the disease in various groups of patients. Obesity is one of the most critical risk factors for NAFLD, with the majority of affected individuals being overweight or obese [19]. Similarly, individuals with metabolic syndrome, characterized by a cluster of conditions including abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and impaired glucose metabolism, exhibit a markedly increased risk of NAFLD [20]. The prevalence of NAFLD is also higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes, with up to 70% showing signs of the disease [21]. Moreover, insulin resistance, a key factor in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, has been recognized as an essential driver of NAFLD [22].

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is notably prevalent among individuals with CVD. Studies indicate an NAFLD prevalence of up to 70% in CVD patients [23]. These patients also face an elevated risk of adverse cardiovascular events, underscoring the relevance of NAFLD as a potential risk factor for CVD [24]. The prevalence of NAFLD in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) is exceptionally high, reaching up to 70%, indicating a potential interactive role between these conditions [25]. Similarly, NAFLD is observed in approximately 50% of patients with heart failure (HF), with HF severity correlating positively with the degree of hepatic steatosis [26]. In hypertensive individuals, NAFLD prevalence is estimated to be about 60%, suggesting a possible influence of hypertension on hepatic lipid accumulation [27]. Lastly, NAFLD’s prevalence in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) is noteworthy, potentially exacerbating AF’s rhythm abnormalities and thromboembolic risk [28].

NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD as a cardiovascular risk factor

Beyond its hepatic manifestations, MASLD is increasingly recognized for its extra-hepatic implications, particularly as a cardiovascular risk factor [29]. The exact mechanisms linking MASLD to increased cardiovascular risk are complex and multifaceted, involving an interplay of metabolic, inflammatory, and vascular pathways. MASLD is strongly associated with insulin resistance, a key driver of systemic metabolic dysfunction and atherogenesis [30]. Hepatic steatosis exacerbates insulin resistance, thereby promoting dyslipidemia, characterized by elevated triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, and a shift towards small, dense LDL particles – a lipid phenotype closely associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [31].

Inflammation is another pivotal link between MASLD and cardiovascular disease. MASLD, especially in an advanced form of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, is characterized by chronic hepatic inflammation. This can spill over into the systemic circulation, increasing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute-phase reactants, which is recognized as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events [32].

Additionally, MASLD may promote a prothrombotic state. Patients with NAFLD exhibit platelet hyperactivity and increased levels of coagulation factors and fibrinolysis inhibitors, which can contribute to atherothrombosis [33]. Endothelial dysfunction, characterized by an impaired vasodilatory response and increased expression of adhesion molecules, is also observed in NAFLD and is an early marker of atherogenesis [34].

Several observational and cohort studies have elucidated the role of MASLD as a cardiovascular risk factor. A meta-analysis by Targher et al. demonstrated that NAFLD patients had a higher prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis, as evidenced by increased carotid artery intima-media thickness and the presence of carotid plaques [35]. A study by Lonardo et al. highlighted that NAFLD patients had a greater likelihood of coronary artery disease, independent of classical risk factors [36]. The Rotterdam study, a prospective cohort study, demonstrated that NAFLD, as diagnosed by ultrasound, was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, further establishing MASLD as a significant cardiovascular risk factor [37]. A recent study by Alexander et al. provided additional evidence, demonstrating that NAFLD is not only associated with prevalent but also incident cardiovascular disease [23].

However, the relationship between MASLD and cardiovascular disease is not merely associative but also appears to be severity-dependent. Patients with more advanced forms of NAFLD, such as NASH and fibrosis, exhibit a higher cardiovascular risk compared to those with simple steatosis [38]. Furthermore, NAFLD’s association with cardiovascular disease holds even in the absence of traditional risk factors, pointing towards a direct contributory role [39].

Mounting evidence supports the role of MASLD as a significant independent cardiovascular risk factor. Through a complex interplay of metabolic, inflammatory, and vascular mechanisms, MASLD exacerbates systemic atherogenesis, promoting the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Hence, cardiovascular risk assessment and management should be an integral part of the clinical approach to patients with MASLD.

Recognition of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD in current cardiology practice guidelines and its clinical implications

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is mentioned in the guidelines of both the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American Heart Association (AHA). NAFLD is recognized as a significant health concern that is often associated with other metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. For instance, in the 2016 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice, NAFLD is recognized as a factor in the multifaceted etiology of cardiovascular diseases, mainly due to its strong association with metabolic syndrome [40]. Also, the updated 2021 ESC guideline recognizes that NAFLD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events due to the high prevalence of overweight or obesity, abnormal blood pressure and glucose, and lipid levels. It also suggests that patients with NAFLD should have their CVD risk calculated and be recommended a healthy lifestyle [41].

In 2022 the AHA released a scientific statement solely dedicated to the association of NAFLD with cardiovascular risk [42]. The paper is a comprehensive review of the current knowledge; it highlights the association mentioned above between NAFLD and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. It also states a need for improved diagnostic strategies for identifying NAFLD and a significant gap in the treatment. AHA states that lifestyle modification that includes 5% to 10% weight loss, increased physical activity, and dietary modification is a key intervention, but further studies are needed to define optimal treatment strategies for preventing both hepatic and cardiovascular complications from NAFLD.

Notably, the AHA scientific statement lists NAFLD risk factors, many of which also contribute to CVD risk [42] (Table 1).

Table 1

Risk factors common for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Modified from ref. [42]

Gaps in current research and future directions

Although our understanding of MASLD as a cardiovascular risk factor has significantly improved, several research gaps still exist. One of the most pertinent gaps is the under-explored molecular and cellular mechanisms connecting MASLD to cardiovascular events. While inflammation, oxidative stress, and lipotoxicity are proposed as linkages, further mechanistic studies are required to establish these relationships [43].

Moreover, epidemiological studies on MASLD predominantly have focused on Western populations, necessitating more diverse studies to extrapolate results globally [44]. Longitudinal studies with larger cohorts are also needed to track the evolution of MASLD and associated cardiovascular events over time. The impact of gender and age on these associations remains under-researched [45].

Screening strategies for cardiovascular risk in MASLD patients also need to be optimized. MASLD is often diagnosed in advanced stages, and patients are already at significant cardiovascular risk [46]. There is a need for broad MASLD screening in both patients at high cardiovascular risk and the general population. Thus, developing early and accurate detection methods is a vital research area, along with exploring novel pharmacological interventions.

Summary

In conclusion, there is a strong relationship between NAFLD and CVD, which are both significant global health concerns. Through the years, NAFLD, now reclassified as MASLD, has evolved as a term and is starting to be better recognized as a risk factor for CVD. There is still a need for further studies, improvement in diagnostics and management, as well as propagation of knowledge on the MASLD-CVD link among patients and health care workers.