Surgical fixation was first reported in 1943 by McKim [1, 2] when he inserted Kirschner wires into the inferior and superior fragments of the sternum and brought them out through the skin. Several surgical techniques for sternal fixation have been described, such as wire cerclage, metal osteosynthesis, nylon bands, Mersilene tape, and locking plates. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal, multidisciplinary approach to healthcare delivery that includes preoperative preparation, intraoperative care and postoperative recovery.

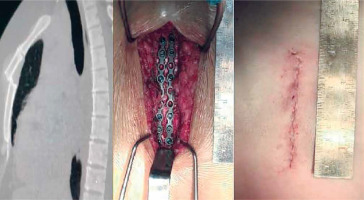

In case 1 a young female, 27 years old, fell from the height of the 4th floor with a friend on her back and the friend landed with his knee on her sternum. In case 2 a man, 35 years old, during jumping on the trampoline, landed on his flexed head. A chest computed tomography (CT) was done in both cases on admission and revealed transverse fracture of the sternum in its middle third in case 1, manubrial-sternal dislocation in case 2. Due to severe pain a surgical reduction was implemented. The patients were treated operatively on the second day in case 1 and on the seventh day in case 2 (Figure 1).

To perform the rigid sternal fixation, we utilized a SANATMETAL LCP plating system with 2.7 mm screw. The plate is made of titanium (Hungary). In both cases, the anesthetic protocol was performed using intravenous anesthesia with spontaneous breathing. The patient was placed in the supine position with both arms tucked along the sides. Standard monitoring included electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, non-invasive blood pressure measurement, measurement of respiratory rate, capnography measured with a detector attached to the oxygen mask and the bispectral index (BIS) to monitor the depth of anesthesia. During the surgery, oxygen supply was maintained through a non-rebreathing mask (oxygen flow 7–10 l/min, FiO2 0.4–0.5). For anesthetic management in these patients, we used a combination of dexmedetomidine, propofol and fentanyl. After insertion of intravenous catheters, dexmedetomidine infusion at a dose of 1 µg/kg for 20 minutes was started. Further, infusion of this drug was continued at a dose 0.7 µg/kg/h and ending before closing the wound. Before surgical incisions, propofol 2 mg/kg and fentanyl 2 µg/kg induction was performed. Surgical incision sites were anesthetized with 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine hydrochloride. Further intraoperative propofol infusion in the first and second case was 4.2 and 3.75 mg/kg/h, respectively. The infusion of fentanyl was 2.6 µg/kg/h in both patients. The target bispectral index value was 40–50. The sternum was exposed through a midline incision. In the first case, the entire length of the incision was around 10 cm and in the second case 9 cm. The incision was then deepened with electrocautery to the sternum. Once the bone was exposed, we reduced the fracture and brought the sternal edges together appropriately. The thickness of the sternum was measured with a depth-measuring device. We used a power screw driver which locks the screws into the plate. We used almost the entire length of the plate (9–10 cm), secured in multiple places (requiring 6 and 8 screws for each plate). Our goal was to support the sternum in its correct anatomical position. Two plates were used, one on each side of the fracture. The transverse fractures were reduced with the plate being fixed proximally and applying gentle manual adjustments without the need for any special equipment (in 1 case, we used a bone reduction clamp). Once the plates had been fully secured, we tightened all the screws with a manual screwdriver. After confirming the stability of the repair by manual palpation, a routine multilayer soft tissue closure was used to complete the procedure. No drains were required. During both operations, there were no problems in the form of unstable hemodynamics or respiratory disorders. Mean arterial pressure and systolic pressure were at the levels 65–93 and 95–120 mm Hg, respectively, and controlled only by infusion of crystalloids 6–10 ml/kg/h. Sat O2 was 95–100%; capnography parameters were also normal, which eliminated the need for assisted lung ventilation. After surgery, the patients were fully awake and returned to the initial department without oxygen supplementation and did not need special care in the ICU. Patients were able to walk and do their activity 2 hours after the operation. On the next day a control CT was done and after that the patients could go home.

The surgical indications for sternal fracture fixation are severe, unrelenting, or intractable pain; respiratory insufficiency or ventilator dependence; displacement, overlapping, or impaction of the fracture; sternal deformity or instability; nonunion; hunched posture; limited range of motion; and presumed eventual pseudoarthrosis of the sternum with chronic-associated pain [3]. The optimal timing of fixation of acutely displaced sternal fractures is not defined in the literature [4]. In our point of view, surgical correction is potentially easier and faster in the acute period of chest trauma, because of the absence of local inflammatory processes and overlap bone deformities.

Non-intubated anaesthesia has been extensively and safely applied to various surgical procedures. In these examples we have shown, with well-controlled, well-monitored anesthetic management, that non-intubated anesthesia may be applicable for surgical fixation of sternal fractures. Non-intubated anesthesia has such advantages as early mobilization, opening of early oral administration, early discharge, and patient satisfaction, and therefore can be considered as part of the ERAS protocol.