Introduction

Cholestasis is a clinical complication that could occur in response to different insults [1, 2]. Several diseases or xenobiotics could induce cholestasis in humans [1, 2]. Irrespective of the etiology of cholestasis, the accumulation of bile constituents primarily affects liver function [1, 2]. Prolonged cholestasis can lead to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatic failure [1-3]. Other organs, apart from the liver, could also be influenced by cholestasis. Renal injury is a prevalent complication in cholestatic/cirrhotic patients and is known as cholemic nephropathy (CN) [4-6]. CN can lead to acute renal failure. On the other hand, the differential diagnosis of CN and accurate differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI) in cholestasis/cirrhosis is a clinical challenge, and standard diagnostic criteria are still missing [7]. Thus, there is an urgent need for more specific clinical tests or biomarkers to diagnose impaired renal function in cholestasis/cirrhosis [7]. Most CN patients might have been diagnosed too late due to inappropriate accuracy of renal injury biomarkers such as creatinine. In addition, CN patients might already exhibit subclinical structural kidney injury that is subsequently prone to AKI and limits therapeutic strategies in these patients. Hence, finding therapeutic options to protect kidneys during cholestasis could have tremendous clinical value.

Hydrophobic bile acids are the most suspicious compounds in the pathogenesis of cholestasis-induced renal injury [4, 5, 8, 9]. It has been well documented that hydrophobic bile acids can disrupt the function of different cellular targets, including biomembrane lipids, various proteins, as well as vital organelles such as mitochondria [8, 10, 11]. Furthermore, previous studies mentioned oxidative stress as a key mechanism in cholestasis-induced renal injury [12-15]. Enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation or decreased antioxidant capacity of renal tissue has been repeatedly mentioned in CN models [12-18]. Interestingly, some studies also reported oxidative stress in the renal tissue of cholestatic patients [19]. Therefore, administering drugs with antioxidative stress capacity in the kidney tissue could protect this organ during cholestasis.

Pentoxifylline (PTX) is clinically administered against peripheral vascular diseases [20]. The improvement of blood cells’ flexibility and deformability is a prominent feature of PTX, which finally leads to improved blood flow in different organs [20]. On the other hand, it has been found that PTX could effectively regulate glomerular filtration and blood flow [20]. Hence, this drug has been repeatedly administered as a renoprotective agent in various experimental models and human clinical trials. Furthermore, the effect of PTX on oxidative stress markers in the renal tissue is an interesting feature of this drug [21-25]. It has been found that PTX significantly blunted oxidative stress and preserved cellular antioxidant capacity in different models of renal disease [21-25].

In this study, we aimed to develop an animal model of cholestasis-related injury to investigate the potential protective effects of PTX administration. Different markers, including inflammatory response and cytokines, oxidative stress biomarkers, renal histopathological alterations, renal tissue fibrotic changes, and finally serum and urine biomarkers of renal injury, were monitored.

Material and methods

Reagents and kits

Sodium acetate, 2,4,6-tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine, p-dimethyl amino benzaldehyde, n-chloro tosylamide (chloramine-T), ethanol HPLC grade, citric acid, perchloric acid, trichloroacetic acid, 5,5’-dithiothreitol, n-propanol, meta-phosphoric acid, sucrose, dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, thiobarbituric acid, ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA), sodium citrate, and 2amino2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol-hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Pentoxifylline, acetonitrile HPLC grade, oxidized glutathione (GSSG), ethyl acetate, methanol HPLC grade, and reduced glutathione (GSH) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Kits for assessing biomarkers of organ injury were purchased from Pars-Azmoon (Tehran, Iran). Urine cytokines were analyzed using LEGENDplex kits (BioLegend).

Animals

We used male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (250-300 g) that are usually used for investigating the adverse effects of cholestasis on the kidney [26, 27]. Animals were purchased from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Animals were kept in plastic cages in a typical environment (a 12L : 12D photoschedule, temperature of 23 ±1°C, and ~40% relative humidity). Rats had access to tap water and a commercial rodents’ diet (RoyanFeed, Esfahan, Iran). All experiments were performed in conformity with the guidelines approved by the ethical committee for using laboratory animals in Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (Code: IR.SUMS.REC.1397.550).

Bile duct ligation operation and the experimental setup

Animals were anesthetized (a mixture of 10 mg/kg of xylazine and 70 mg/kg of ketamine, i.p.), and a midline laparotomy was made through the linea alba. The bile duct was identified, doubly ligated, and cut [15, 28-30]. The sham operation involved laparotomy and bile duct localization without ligation. Animals (n = 40) were equally allotted to five groups containing 12 rats in each. Rats were treated as follows: 1) Control (sham-operated, vehicle-treated), 2) Bile duct ligated (BDL), 3) BDL + PTX (10 mg/kg/day, oral, for 14 consecutive days), 4) BDL + PTX (50 mg/kg/day, oral, for 14 consecutive days), 5) BDL + PTX (100 mg/kg/day, oral, for 14 consecutive days) [26, 31]. Cholestasisinduced renal injury was evaluated 14 days after the BDL operation.

Urinalysis and serum biochemistry

Urine samples were collected (200 µl) during animal handling and diluted with ice-cold normal saline (200 µl, 4°C) [32, 33]. Afterward, samples were centrifuged (1000 g, 5 min, 4°C), and the clear supernatant was collected. Enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT) are usually released from damaged renal tubular cells and indicate the loss of microvilli during kidney injury [34]. These enzymes are usually used in the urine sample to enhance our understanding of renal damage, monitor the extent of renal injury, and evaluate the response to therapeutic options [34]. Then, animals were deeply anesthetized (thiopental 80 mg/kg, i.p.). Next, blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta, centrifuged (3000 g, 15 min, 4°C), and the serum was collected. Serum markers of renal injury, including blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, were assessed in the investigated animals.

Renal histopathological assessments and organ weight index

Kidney samples were fixed in a buffered 10% v : v formalin solution (formaldehyde in phosphate buffer, pH = 7.4). Then, tissue sections (5 µm) were prepared and stained (hematoxylin and eosin – H&E). Kidney fibrosis was monitored by Masson’s trichrome staining [35, 36]. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain was used to monitor renal casts [37]. The organ weight indices were measured as organ weight index = [wet organ weight (g)/whole body weight (g)] × 100.

Reactive oxygen species formation

2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) was used to estimate reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation in the kidney tissue [15, 38-40]. Briefly, 200 mg of kidney tissue was homogenized in 5 ml of ice-cooled 40 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 7.4). Then, 100 µl of the resulted homogenate was mixed with 1 ml of Tris-HCl buffer (40 mM) and DCF-DA (10 µl, final concentration 10 µM). The mixture was incubated at 37°C (15 min, in the dark). Finally, the fluorescence intensity was measured using a FLUOstar Omega fluorimeter (λ = 485 nm excitation and λ = 525 nm emission wavelengths) [15, 41-45].

Lipid peroxidation in the renal tissue

The lipid peroxidation in cholestatic rats’ renal tissue was assessed using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) test [15, 46, 47]. Briefly, 500 µl of 10% w : v tissue homogenate (in 1.15% w : v KCl) was mixed with thiobarbituric acid (1 ml of 0.375%, w : v solution), trichloroacetic acid (50% w : v), and 1 ml of 6N HCl (pH = 2). Samples were mixed well and heated at 100°C (45 min in a water bath) [15, 46, 48-50]. Afterward, the mixture was cooled, and then 2 ml of n-butanol was added. Samples were mixed well and centrifuged (10,000 g, 10 min, 4°C). Finally, the absorbance of developed color in the upper phase was measured at λ = 532 nm using the EPOCH Plate reader (BioTek, USA) [15, 33, 51].

Renal oxidized and reduced glutathione content

Renal glutathione (GSH and GSSG) content was measured using HPLC [32, 52, 53]. Briefly, tissue homogenate (1 ml) was treated with 100 µl of ice-cooled perchloric acid (10%), mixed well, incubated on ice (15 min), and then centrifuged (17,000 g, 30 min, 4°C) [52, 54]. The supernatant was collected in 5 ml tubes and treated with 300 µl of NaOH : NaHCO3 (2 M : 2 M) and 100 µl of iodoacetic acid (1.5% w : v in HPLC grade water) respectively. Then, samples were incubated at 4°C (one hour, in the dark). Afterward, 0.5 ml of 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB; 1.5% v : v in absolute ethanol; HPLC grade) was added and incubated in the dark (25ºC, 24 h). The HPLC system was composed of an amine column (NH2; 25 cm, Bischoff chromatography, Germany) as the stationary phase. The mobile phase consisted of buffer A (acetate buffer : water; 1 : 4 v : v) and buffer B (buffer A : methanol; 1 : 4 v : v). A gradient method with a continual increase of buffer B to 95% in 30 minutes was used. The flow rate was 1 ml/min, and the UV detector was set up at λ = 254 nm [52, 55, 56].

Kidney tissue ferric reducing antioxidant power

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) test was applied to measure renal total antioxidant capacity in cholestatic rats [15, 57]. Briefly, the FRAP working reagent was freshly prepared by mixing 25 ml of 300 mM acetate buffer (pH = 3.6) with 2.5 ml of 10 mM TPTZ (dissolved in HCl 1N) and 2.5 ml of ferric chloride (FeCl3.6H2O, 20 mM). Then, 200 mg of the kidney tissue was homogenized in an ice-cooled 250 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 7.4) [15, 38, 58]. Then, 100 µl of tissue homogenate was added to 900 µl of the working FRAP reagent [15, 58]. The mixture was incubated in the dark (5 min, 37°C). Finally, the absorbance was measured at λ = 595 nm using an EPOCH Plate reader (BioTek, USA) [15, 59].

Kidney hydroxyproline level

Renal hydroxyproline content was measured using Ehrlich’s reagent (p-dimethyl amino benzaldehyde, 15 g in n-propanol/perchloric acid; 2 : 1 v : v) [60]. Briefly, kidney homogenate (1 ml of 10% w : v in KCl) was digested in 1 ml of 6 N HCl (at 120°C for 24 h). Then, an aliquot (25 µl) of digested tissue was added to a Petri dish and treated with citrate-acetate buffer (25 µl, pH = 6) and dried at room temperature (25°C). Then, 0.5 ml of chloramines-t-solution (56 mM) was added and incubated at 25°C for 20 minutes. Afterward, 0.5 ml of Ehrlich’s reagent was added, and the mixture was incubated in a 65°C water bath for 15 minutes. The absorbance was assessed at λ = 550 nm (EPOCH plate reader, USA) [60, 61].

Statistical methods

Data are given as mean ±SD. The data sets were compared by the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons as the post hoc test. Histopathological scores are represented as median and quartiles for five random pictures per group. Renal tissue histopathological changes analysis was performed by the Kruskal-Wallis followed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

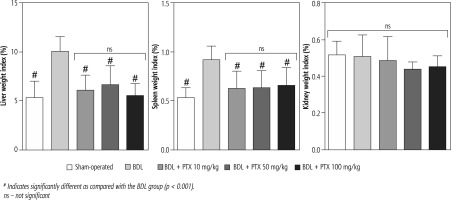

Signs of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were evident in cholestatic rats as assessed 14 days after the BDL surgery. No significant changes in the renal weight index were detected in BDL animals. It was found that the PTX (10, 50, and 100 mg/kg, 14 consecutive days) significantly mitigated signs of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly in BDL rats. The effect of PTX on spleen and liver weight indices was not dose-dependent in the current model (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Organ weight index in bile duct ligated (BDL) rats. Data are given as mean ±SD (n = 8)

# Indicates significantly different as compared with the BDL group (p < 0.001).

ns – not significant

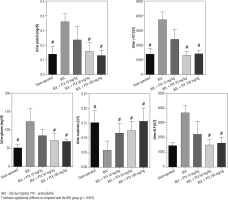

Serum biochemical analysis revealed a significant increase in markers of cholestatic liver injury (high serum ALP and γ-GT) and increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and bilirubin levels in BDL rats (Fig. 2). Moreover, serum creatinine was significantly higher than the control levels, as assessed 14 days after the BDL operation (Fig. 2). No significant changes in serum BUN levels were detected in the current study (Fig. 3). It was found that the PTX significantly ameliorated serum markers of organ injury in cholestatic rats (Fig. 2). The effect of PTX on serum biomarkers of organ injury was not dose-dependent in the current study (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Serum biochemical measurements in bile duct ligated (BDL) rats treated with pentoxifylline (PTX). Data are given as mean ±SD (n = 8)

# Indicates significantly different as compared with the BDL group (p < 0.001)

Fig. 3

Urine biochemistry of cholestatic rats. Data are given as mean ±SD (n = 8)

BDL – bile duct ligated, PTX – pentoxifylline

# Indicates significantly different as compared with the BDL group (p < 0.001)

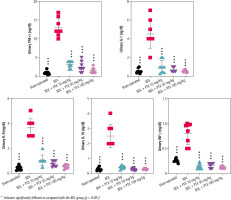

Urinalysis revealed significant urine ALP, glucose, creatinine, protein, and γ-GT changes as markers of renal injury in BDL rats (Fig. 3). On the other hand, it was found that PTX significantly ameliorated urine biomarkers of renal damage in BDL rats (Fig. 3). Urinary cytokine levels, including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-9, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and interferon γ (INF-γ), were significantly higher in the BDL group (Fig. 4). On the other hand, PTX dose-dependently significantly decreased urinary cytokines in the cholestatic animals (Fig. 4). The effect of PTX on urine biomarkers was not dosedependent in the current model (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 4

Urinary level of pro-inflammatory cytokines in cholestatic animals. Data are given as mean ±SD (n = 8)

*** Indicates significantly different as compared with the BDL group (p < 0.001)

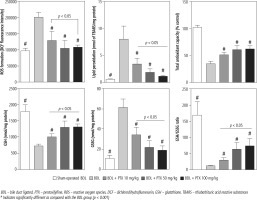

Markers of oxidative stress were evaluated in BDL animals treated with PTX (Fig. 5). The ROS level, GSSG, and lipid peroxidation were significantly increased in BDL rats (Fig. 5). Moreover, renal GSH levels, GSH/GSSG ratio, and total tissue antioxidant capacity were significantly decreased in the BDL group (Fig. 5). It was found that PTX significantly blunted markers of oxidative stress in cholestatic animals (Fig. 5). The effects of PTX on renal biomarkers of oxidative stress were not dose-dependent in the current investigation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Kidney oxidative stress markers in bile duct ligated rats. Data are given as mean ±SD (n = 8)

BDL – bile duct ligated, PTX – pentoxifylline, ROS – reactive oxygen species, DCF – dichlorodihydrofluorescein, GSH – glutathione, TBARS – thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

# Indicates significantly different as compared with the BDL group (p < 0.001)

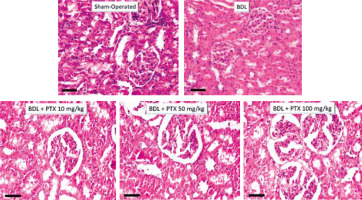

Kidney histopathological changes in BDL rats included tubular atrophy and interstitial inflammation, as assessed 14 days after BDL induction (Fig. 6; H&E stain and Table 1). In addition, it was found that PTX ameliorated renal histopathological alterations in BDL animals (Fig. 6; H&E stain and Table 1).

Fig. 6

Effect of pentoxifylline (PTX) treatment on kidney histopathological alterations in cholestatic rats. H&E stain, scale bar = 100 μm. Tubular atrophy and interstitial inflammation were detected in the kidney of cholestatic rats

Table 1

Scores of renal tissue histopathological alterations in cholestatic rats

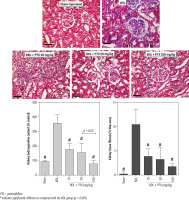

A significant amount of hydroxyproline level was detected in the kidney tissue 14 days after the BDL operation (Fig. 7, Trichrome stain). On the other hand, tissue histopathological evaluation by Trichrome-Masson stain revealed a significant amount of collagen deposition in the renal tissue of BDL animals (Fig. 7; Trichrome stain). It was found that PTX dosedependently decreased markers of kidney fibrosis in cholestatic rats (Fig. 7). The effect of PTX on renal hydroxyproline levels and collagen deposition was not dose-dependent (Fig. 7; Trichrome stain).

Fig. 7

Kidney tissue histopathological changes, fibrosis, and hydroxyproline content in bile duct ligated (BDL) rats. Trichrome stain, scale bar = 100 μm. Data for hydroxyproline content and tissue collagen deposition are represented as mean ±SD (n = 8)

PTX – pentoxifylline

# Indicates significantly different as compared with the BDL group (p < 0.001)

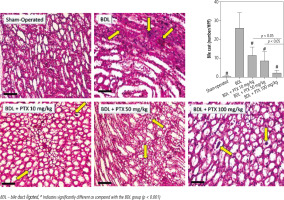

A significant increase in renal cast formation was evident in the BDL group (Fig. 8; PAS stain and Table 1). In addition, it was found that PTX treatment dose-dependently decreased bile cast formation in the kidney of cholestatic animals (Fig. 8; PAS stain and Table 1).

Fig. 8

Effect of pentoxifylline (PTX) administration on cast formation (yellow arrow) in the kidney of cholestatic animals (periodic acid-Schiff; PAS, stain, scale bar = 200 μm). Data are given as mean ±SD (n = 10)

BDL – bile duct ligated, # Indicates significantly different as compared with the BDL group (p < 0.001)

It should be noted that the serum level of several biomarkers such as ALP, bilirubin, and γ-GT was persistently high in cholestatic animals and showed no response to PTX treatment. This could be due to the persistent obstruction of the bile duct in the current model.

Discussion

Cholestasis could occur in response to different xenobiotics or diseases [62]. The liver is the main organ influenced by cholestasis [62]. On the other hand, renal injury is a prevalent complication during cholestasis [63]. No specific therapeutic intervention has been identified for the management of cholestasis-associated renal injury. The current study found that PTX (10, 50, and 100 mg/kg) significantly protected renal tissue in cholestatic animals. The effects of PTX on oxidative stress biomarkers seem to play a central role in its renoprotective properties in the current model.

Effect of PTX on oxidative stress markers

The precise renal injury mechanisms of CN are far from clear. However, oxidative stress and its associated complications seem to play a fundamental role in CN [12-15, 64, 65]. Interestingly, some studies also mentioned the occurrence of oxidative stress in human CN cases [19]. In the current study, a significant amount of ROS was detected in the kidney of cholestatic animals. Other indices, such as decreased tissue antioxidant capacity and GSH levels, indicated oxidative stress in the kidney tissue (Fig. 4). Our data are in agreement with investigations that identified the occurrence of oxidative stress in the kidney of cholestatic animals [12-15]. On the other hand, we found that PTX dose-dependently diminished oxidative stress in cholestatic animals’ renal tissue. The effects of PTX on cellular antioxidant systems or its direct interaction with reactive species have been proposed as the underlying mechanisms for this drug’s antioxidative effects [66, 67]. Based on these data, the role of PTX in mitigating oxidative stress could play a basic role in its nephroprotective properties in cholestatic rats.

PTX mitigates the inflammatory response in CN

The anti-inflammatory properties of PTX are another potential mechanism that might be involved in its nephroprotective properties during CN. Previous studies mentioned that PTX could significantly suppress renal inflammation [68]. It has been found that PTX robustly suppressed cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α) in diabetes-associated nephropathy [68]. It has also been reported that PTX modulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and INF-γ in different experimental models [69, 70]. On the other hand, interstitial inflammation is a common histopathologic finding in CN (Fig. 6; H&E stain). The current study found that PTX treatment significantly decreased urinary cytokines in BDL rats (Fig. 4). Therefore, an essential part of the nephroprotective role of PTX in cholestatic animals could be mediated through the effects of this drug on the inflammatory response. On the other hand, the inflammatory response and oxidative stress are mechanistically interrelated [71]. The infiltration of inflammatory cells could enhance ROS formation in tissues such as the kidney [71]. Hence, the anti-inflammatory effect of PTX could mitigate oxidative stress in the kidney of cholestatic animals. More investigations on the anti-inflammatory properties of PTX in CN might help clarify the mechanism of its renoprotective effects.

Effect of PTX on renal fibrosis

The effect of PTX in mitigating renal tissue fibrosis was another interesting finding in the current study. It was found that PTX significantly decreased collagen deposition in cholestatic animals (Fig. 7). Previous studies also mentioned the anti-fibrotic effects of this drug in different experimental models [72, 73]. Tissue fibrosis is a complex process that finally leads to organ failure [74]. On the other hand, it has been well documented that oxidative stress and the inflammatory response play a pivotal role in tissue fibrosis [75-78]. As mentioned, PTX significantly decreased oxidative stress biomarkers and the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the current study (Fig. 5). Moreover, the anti-inflammatory effects of this drug have also been mentioned in previous studies [69]. Based on these data, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of PTX could be involved in its anti-fibrotic effects. Furthermore, the effects of PTX on specific signaling molecules involved in tissue fibrosis (e.g., transforming growth factor β – TGF-β) could give a better insight into its anti-fibrotic mechanisms in CN.

Role of PTX in renal blood flow and its potential renoprotective effects

Renal blood circulation disturbance is another critical factor that could affect kidney damage during CN. As mentioned, PTX acts as a modulator of blood rheology [20, 68]. On the other hand, several investigations indicated the effects of PTX on renal hemodynamic factors as an essential mechanism for its nephroprotective properties [68]. Therefore, the effects of PTX on homodynamic changes in the kidney during cholestasis could be an exciting field of investigation.

Effects of PTX on renal casts in cholestasis

Bile cast formation is a common feature of CN [7].It has been reported that bile casts in the kidney significantly correlated with the degree of cholestasis. Bile casts in cholestasis can consist of exfoliated epithelial cells, bile acids, and bilirubin, levels of which dramatically increase during cholestasis. Casts can be easily confirmed by histochemical Hall (or Fouchet) staining or periodic-acid Schiff (PAS) stains of kidney sections [7]. Cast formation could induce tubular cellular injury through different mechanisms [7]. First, it has been reported that casts contribute to kidney injury by direct toxicity of their bilirubin and bile acid constituents [7]. Second, cast formation could physically damage tubular cells and lead to a leaky tubule. Thus, the accumulation of toxic urine components could damage the kidney. The dose-dependent effect of PTX in decreasing renal casts was an exciting finding in the current study. Interestingly, previous studies indicated that renal hypoperfusion could enhance cast formation and acute kidney injury [79]. As previously mentioned, PTX could act as a modulator of blood rheology, increase renal blood flow, and enhance glomerular filtration rate [20, 68, 80]. Based on these data, a potential mechanism for the effects of PTX on renal casts during cholestasis could be mediated through its impact on renal hemodynamic parameters. However, further studies in this field could shed more light on this subject.

Conclusions

Several clinical trials mentioned the positive effects of PTX on nephropathy with different etiologies. Therefore, PTX administration in CN might also find a clinical application in the future. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and anti-fibrotic properties of PTX, along with its effects on hemodynamic changes, make this drug an excellent renoprotective candidate. Indeed, further investigations are warranted to identify other mechanisms for the nephroprotective effects of PTX and finally establish the current data’s clinical relevance.