Hydatid cyst is a zoonotic larval infection caused by Echinococcus granulosus, which demonstrates a global distribution with a higher prevalence in livestock farming regions in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, India, and Oceania [1]. Humans are incidental intermediate hosts, while animals such as dogs, wolves, and foxes serve as definitive hosts [2]. Hydatid cysts arise most commonly in the liver (60%) and the lungs (30%), while other sites include the spleen, kidneys, bones, muscles, and brain. Primary muscular hydatidosis is an uncommon clinical entity, with incidence ranging from 1% to 5%, and the most frequently affected locations are the roots of the limbs and the trunk [3–5].

Herein, we report a case of an 82-year-old female living in a rural setting, exhibiting a painless mass on her left thigh persisting for 3 years. Additionally, she reported experiencing a mild fever, which commenced 5 days prior to her hospital admission. She had a medical history notable for atrial fibrillation, arterial hypertension, and appendicectomy. Her physical examination yielded no significant findings, except for the palpable mass. An ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imagibg (MRI) scan, initially conducted at a different institution, prompted concerns regarding the existence of a hydatid cyst. Subsequently, this was confirmed following fine-needle aspiration and a positive serology test for Echinococcus granulosus. The patient underwent a PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration) procedure twice, coupled with a 6-month course of albendazole. However, she was subsequently referred to our hospital due to multiple recurrences. Upon re-evaluation, laboratory tests indicated an elevated white blood cell count and increased C-reactive protein levels, with no other abnormal findings. A follow-up MRI scan revealed multiloculated cystic lesions in the medial compartment of her left thigh with high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Figure 1). No other organs were affected. The diagnosis of a secondary thigh infection, along with signs of septicaemia, in the context of recurrent primary muscular hydatid cyst, was established, and the patient was treated with antibiotics. Subsequently, she underwent another PAIR session, which yielded suboptimal results, without adequate drainage of the cyst (Figure 2). The multidisciplinary team advised surgical removal of the hydatid cyst located in her left thigh, a procedure that was executed alongside partial excision of the affected muscles (Figure 3). Subsequent histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis. Following surgery, the patient received Albendazole treatment for 6 months. At the 6-month follow-up, there was no evidence of recurrence.

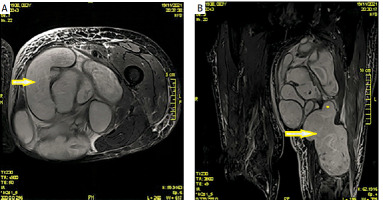

Figure 1

T2-weighted axial (A) and coronal (B) images depicting high-signal-intensity, multiloculated cystic lesions involving the medial compartment of the left thigh

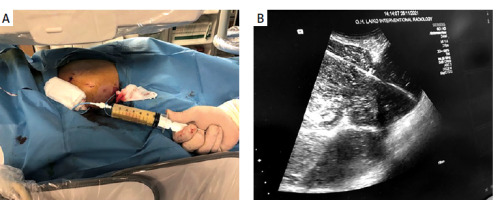

Figure 2

A – PAIR procedure. B – Ultrasound image during PAIR showing drainage catheter in the cystic lesion

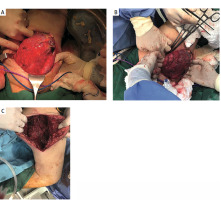

Figure 3

A – Intraoperative picture of echinococcal cyst upon incision. B – Intraoperative picture during initial dissection. C – Surgical field after complete excision

Primary muscular hydatidosis is an infrequent parasitic infection caused by the cestode of the Taeniidae family, with subcutaneous colonisation following the haematogenous circulation of the consumed eggs being the dominant possible theory of development. A second theory suggests direct contamination of injured skin as a potential mechanism [5]. Clinical presentation depends mostly on the localisation and size of the cyst, with the most prevalent manifestation being the painless progressively enlarging mass [2, 6]. Various imaging modalities such as ultrasound (U/S), computed tomography (CT), and MRI are employed in the diagnosis of primary muscular hydatid cysts. Ultrasonography (U/S) is often favoured as the initial diagnostic tool due to its widespread availability and absence of radiation exposure. U/S can effectively discern the distinctive features of echinococcal cysts, including daughter cysts and the detachment of germinal membranes from the cyst wall [6]. A CT scan has the capability to accurately determine the specific location, quantity, dimensions, and presence of wall calcifications within the cyst, while MRI is the imaging test of choice because of the improved soft tissue contrast that allows more accurate identification of soft tissues masses [3, 7]. Although there are only a few cases in the literature where fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has been employed preoperatively, it is regarded as an effective alternative diagnostic test [5, 8]. Considering the risk of anaphylactic reactions intraoperatively, the preoperative diagnosis of primary hydatid cysts of the limbs is fundamental, and serology for echinococcus granulosus can facilitate the differential diagnosis from abscess, hernia, lipoma, sarcoma, sebaceous cyst, and haematoma [5]. Treatment approaches should be customised based on the patient’s clinical symptoms, the site of the cyst, and any associated complications. Radical surgical excision remains the treatment of choice for primary muscular hydatid cysts. Although PAIR treatment has been used in echinococcal cysts of the extremities, it has poorer success rates compared to hepatic cysts, because subcutaneous cysts are usually multiloculated [5, 9]. Anthelminthic medication preoperatively and postoperatively is widely employed in most treatment protocols to eliminate the possibility of anaphylactic reaction and recurrence, respectively [10]. In the aforementioned case, our patient presented with a concurrent infection along with recurrent primary hydatid cyst of the left thigh. The diagnosis was established and confirmed preoperatively, and the definitive treatment was radical surgical resection, which was achieved with an uneventful postoperative course.

This case highlights the significance of including primary hydatid cysts of the extremities in the differential diagnosis when patients from endemic regions present with painless soft tissue masses.