Introduction

Pruritus is a common complaint among patients with dermatological disorders. Chronic pruritus is an unpleasant skin sensation that causes the urge to scratch the skin and can present with or without skin lesions for at least 6 weeks. It is also a common symptom in geriatric patients [1], and is increasingly becoming a reason for consultation in dermatology outpatient clinics and hospitalisation in dermatology departments. The prevalence of pruritus in elderly patients has been estimated to be between 11% and 46% [1–3].

Several pathophysiological mechanisms of itch in the geriatric population have been reported, with the most common being xerosis, neuropathy, and immunosenescence. Xerosis, or dry skin, is considered the most frequent cause of pruritus in the elderly population. There is a suggested association between xerosis and pruritus, which may be caused by an acquired abnormality of the keratinisation process leading to a reduced amount of water in the stratum corneum [4]. The use of emollients can help to reduce the incidence of pruritus in most patients. Additionally, chronic pruritus may be associated with age-acquired damage to the central and peripheral nervous systems [5–7]. Neuropathic pruritus is a common condition in elderly patients, observed in several conditions such as hemiplegia, diabetes, or neurodegenerative diseases of the central nervous system [8]. Immunosenescence, the changes in the immune system resulting from ageing, affects both acquired and innate immunity [9–11]. This process can induce increased autoreactivity of the immune system, leading to autoimmune disease. The pathogenesis of chronic pruritus may be multifactorial in many patients. Chronic pruritus can be caused by various factors, including dermatoses, systemic, neurological, or psychiatric conditions. Systemic conditions that can cause pruritus include chronic kidney or liver disease, endocrine and haematological diseases, which are statistically more common in older patients. Paraneoplastic pruritus is more likely to develop in older patients with cancer. Additionally, pruritus can be drug-induced due to polypharmacy in many elderly patients. Pruritus may be an early or sole symptom of various conditions.

It can significantly affect patients’ quality of life and sleep, particularly in the elderly population. Studies have shown that the detrimental effects of chronic pruritus are comparable to those of chronic pain [9, 12]. In fact, most patients would prefer to live a shorter life without symptoms than to live longer and struggle with chronic pruritus. This highlights the impact of pruritus on the quality of life in patients.

Aim

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of pruritus in a geriatric population using standardised pruritus assessment methods as well as to characterise pruritus and explore possible underlying causes.

Material and methods

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in the Care and Treatment Facility (CTF) and Geriatric Outpatient Clinic (GOC) affiliated with the City Medical Center between March 2022 and June 2022. One hundred and thirty-two participants aged 65 years or older were included in the study (102 women, 30 men, mean age: 81.85 ±7.77 years with a range of 65–97). The exclusion criteria were systemic immunosuppressive therapy or acute mental disorders.

All participants who were able to participate and provided written informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The local Ethics Committee of the Medical University approved the study. Patients were interviewed about their medical history, the presence of pruritus, and their use of emollients. Patients who reported pruritus were asked about its duration, whether it was acute (lasting less than 6 weeks) or chronic (lasting more than 6 weeks), and its location. They were asked to complete the 10-Item Pruritus Severity Scale (10-PSS), developed by Bożek and Reich in 2018 [13]. The questionnaire comprises 10 questions that evaluate pruritus intensity (two questions), extent (1 question), and duration (1 question) as well as the influence of pruritus on focus and patient psyche (4 questions) and scratching as a response to pruritus stimuli (two questions) in the last 24 h. Pruritus intensity was assessed among patients using the itch Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), evaluating the presence of the worst itch in the last 24 h. The interpretation criteria for VAS based on literature data are as follows: 0 indicates no itch, 1 – < 4 points indicates mild itch, ≥ 4 – < 7 points indicates moderate itch, ≥ 7 – < 9 points indicates severe itch, and ≥ 9 points indicates very severe itch [14]. The intensity of pruritus measured using NRS can be categorized as no (0 point), mild (1–3 points), moderate (4–6 points), severe (7–8 points), and very severe pruritus (≥ 9 points) [1]. The study analysed the medical records of all patients, with a focus on comorbidities, medications (including antihypertensives, diuretics, statins, antidiabetics, and opiate analgesics), and laboratory tests. A skin examination was conducted in all patients to identify symptoms such as xerosis, erosions, and excoriations. The overall skin dryness score (ODS), developed by the European Group on Efficacy Measurement of Cosmetics and other Topical Products (EEMCO), was used to assess xerosis. Scores ranged from 0 (indicating no xerosis) to 4 (indicating extensive scaling, significant roughness, presence of redness, eczematous lesions and cracking) [15].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13 software. Continuous variables were presented using mean and standard deviation, while numerical and non-continuous variables as number of cases (N) and percentage. Distribution of variables was evaluated using Shapiro-Wilk test. To compare differences between groups, Welch’s and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for continuous variables, while χ2 tests (Pearson’s test, and with Yates’ correction) were employed for categorical variables. The correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman correlation coefficient. A correlation coefficient ranging from 0.00 to 0.19 was considered as very weak, 0.20 to 0.39 as weak, 0.40 to 0.59 as moderate, 0.60 to 0.79 as strong and 0.80 to 1.0 as very strong. A p < 0.05 was deemed significant for all analyses.

Results

A total of 132 subjects aged 65 and over from GOC and CTF were included in the study. Among the study cohort, 105 (79.55%) patients with a mean age of 81.82 ±7.07 confirmed the presence of pruritus. Of these patients, 84 (80%) were female and 21 (20%) were male. Sixty-six out of 105 patients attended GOC, while the remaining patients resided in CTF. A group of 27 subjects (mean age: 81.96 ±10.24) denied pruritus, of which 2/3 were female. Table 1 shows that slightly over half of the patients attended GOC.

Table 1

Characteristics of studied population. Comparison between patients with and without pruritus

[i] M – male, F – female, CTF – Care and Treatment Facility, GOC – Geriatric Outpatient Clinic, WBC – white blood count, RBC – red blood count: MCV – mean corpuscular volume, MCH – mean corpuscular haemoglobin, MCHC – mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration, PLT – platelet, ALT – alanine transaminase, AST – aspartate transaminase, TSH – thyroid-stimulating hormone, LDL – low-density lipoprotein, HDL – high-density lipoprotein.

There were no statistically significant differences between patients with and without pruritus regarding comorbidities. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity observed in both groups, followed by cardiovascular diseases and hyperlipidaemia. The analysis of laboratory results revealed that glucose levels were significantly higher among those with pruritus. Although statistical significance was lacking, there was an observable trend towards an increased incidence of pruritus among diabetic patients. Other laboratory parameters were within normal limits and did not differ significantly between the two groups of patients. Detailed data are presented in Table 1.

It was found that patients with pruritus had a significantly higher (p = 0.0005) incidence of xerosis (observed in 82.86 % of patients) compared to patients without pruritus (48.15%). Among patients reporting pruritus, 5 used emollients. Erosions and excoriations were observed in 7.62% and 30.48% of patients who reported pruritus, respectively. However, even in patients who did not report pruritus, erosions and excoriations were observed on skin examination in 7.41% and 15.38%, respectively (refer to Table 1).

The ODS score indicated that most patients had mild xerosis. For detailed data, please see Table 2.

Table 2

Demographic and clinical characteristics of xerosis

In this study, 71.43% (75/105) of patients had chronic pruritus, which was predominantly generalised (65.71%). The intensity of itch was measured using the mean VAS score of 3.76 ±1.60 (range: 0–10) points and the mean NRS score of 4.17 ±1.63 (range: 0–10) points. Additionally, the mean result of 10-PSS was 6.22 ±2.35.

Almost all patients (104/105) showed the presence of at least one concomitant systemic pruritic disorder. Itchy skin conditions were observed in 12.38% (13) of patients. Of the 13 patients with pruritic skin disorders, we observed 4 cases of rosacea, 3 cases of psoriasis, 2 cases of seborrheic dermatitis, 2 cases of hand eczema, 1 case of chronic urticaria, and 1 case of pityriasis rubra pilaris. Among other concomitant disorders, psychiatric and neurological conditions were present in 32.38% (34) and 30.48% (32) of patients, respectively. Additionally, 12 patients had a history of stroke. Diabetes was observed in 46.67% (49) of the subjects, while thyroid disorders were observed in 23.81% (25) (refer to Table 3).

Table 3

Clinical characteristics of patients with pruritus

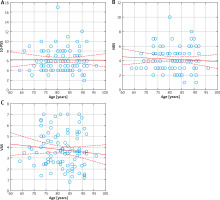

No significant correlation was found between age and pruritus severity in the individual scales (Figures 1 A–C).

The 10-PSS, NRS, and VAS scores did not differ significantly between genders. Patients from the geriatric outpatient clinic had similar scores on all scales to those from the care and treatment facility. Patients with anaemia had significantly higher 10-PSS scores than those without anaemia (p = 0.0263). None of the other comorbidities analysed had an impact on the results of the 10-PSS, VAS and NRS scales (Table 4).

Table 4

Impact of sex and concomitant diseases on pruritus severity

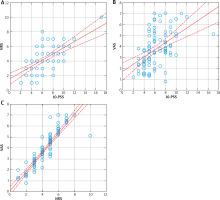

We found a strong correlation between all scales (p < 0.001), with the highest correlation observed between VAS and NRS (Figures 2 A–C).

We observed a significantly higher incidence of pruritus in patients who used antihypertensive drugs, antidiabetic drugs and/or statins, compared to patients who did not use these medications (p < 0.05). However, we did not observe similar results for xerosis.

Discussion

Our study found that pruritus is a common issue among the elderly population. We considered both chronic pruritus lasting more than 6 weeks and intermittent pruritus of shorter duration. Skin pruritus was reported by 79.55% (105/132) of the patients, with 71.43% of those patients diagnosed with chronic pruritus. These results are significantly higher than those reported in the literature. According to the literature, pruritus was observed in 11–46% of geriatric patients [16], and its prevalence increased with age. In the age group of 65–74 years, the prevalence of pruritus was around 10%, and after the age of 85 years, it was around 20% [2]. In a study conducted on another Polish group of geriatric patients, the prevalence of pruritus was 35.3% [17]. The higher prevalence of pruritus among our patients may be due to multiple comorbidities and a higher risk of pruritus.

There was no correlation found between the prevalence of pruritus and comorbidities. Although the trend was not statistically significant, there was a slight increase in the prevalence of pruritus among patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). The prevalence of pruritus in individuals with diabetes ranges from 18.4% to 35.8% [18]. However, the exact prevalence is still underestimated. Researchers currently suggest that there are two main factors associated with pruritus in DM, namely diabetic polyneuropathy and skin xerosis. Diabetic patients may develop neuropathic pruritus as a result of polyneuropathy [19]. Studies have shown that diabetes-induced peripheral nerve damage can cause pruritus of the trunk [19], while geriatric patients with diabetes have been found to have an association with pruritus of the scalp [1].

Our study revealed that patients with pruritus had a significantly higher prevalence of xerosis (p = 0.0005) compared to those without pruritus. Xerosis, also known as dry skin, is considered the most common cause of pruritus in the elderly population, with prevalence estimates ranging from 38% to 85% in various studies [20]. A study by Reszke et al. found that xerosis was present in 94.1% of patients, with a median intensity score of 2 points [17]. Xerosis is associated with several changes in the skin of the elderly, including an increase in skin pH, impaired epidermal barrier function, or reduced sweat and sebaceous gland activity [21]. It is agreed among researchers that patients with xerosis should regularly use emollients and moisturisers, up to twice a day. Emollients and moisturisers containing antipruritic active substances, such as urea, polidocanol, menthol, or palmitoylethanolamide, are highly recommended [22].

Studies investigating the association of pruritus with various comorbidities have also highlighted the presence of xerosis in patients complaining of pruritus. Clinically examined xerosis was found to be significantly more advanced in patients with pruritus associated with DM 2 compared to those without pruritus (p < 0.01) [18]. Xerosis and pruritus are particularly prevalent among patients with stage 5 CKD/chronic kidney disease undergoing haemodialysis [23, 24].

Studies on the impact of xerosis on patients’ quality of life have shown that those with cutaneous xerosis experience more psychosocial burden than those without [25].

Only 13 of the patients reporting pruritus had a previously diagnosed dermatosis, which could be the cause of the pruritic complaints. According to the literature, all dermatoses described in our patients can cause pruritus. In cases where hand eczema or rosacea were present, the pruritus was localized. Erosion and excoriation symptoms were observed in 8 and 32 patients, respectively, who experienced pruritus. As stated in the literature, pruritus can be the sole or accompanying symptom of various dermatoses and may precede the appearance of typical symptoms for many months. Therefore, it is crucial to examine this issue closely and give it the attention it deserves. There are growing reports of pruritus as an early or sole manifestation of various autoimmune conditions, such as bullous pemphigoid or systemic sclerosis [26]. In fact, in one out of every 5 patients with pemphigoid, typical blisters are not present. Non-bullous pemphigoid [27] is a condition that presents with severe pruritus and a wide range of clinical symptoms, which can resemble other pruritic skin diseases. This often leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment. A study conducted in 7 Dutch nursing homes confirms this. The study found that 6% of pemphigoid cases were of the non-bullous variant, with over half of the patients having no prior diagnosis and presenting without bullae [28]. This variant appears to be an unrecognized cause of pruritus [29], due to its atypical clinical presentation. Currently, pruritus in systemic sclerosis (SSc) has not been extensively researched. Research has demonstrated that pruritus was present on most days in 45% of patients, and those who complained of pruritus had more significant skin involvement, worse respiratory symptoms, and more gastrointestinal complaints [30]. Patients with pruritus during the course of SSc experience poorer mental and physical functioning and more disability than those without pruritus [31]. The origin of pruritus in systemic sclerosis remains unclear. However, it is important to understand the mechanisms leading to its origin to improve the quality of life of patients [32]. None of our patients had previously received a diagnosis of pemphigoid or scleroderma. Based on literature reports of atypical variants of pemphigoid and scleroderma, it would be advisable to perform diagnostics for these diseases, particularly in patients with pruritus-associated erosions and excoriations.

No significant correlations were found between age, gender, or presence of comorbidities and the severity of pruritus in VAS, NRS, and 10-PSS scales, except for patients with anaemia who achieved a significantly higher 10-PSS score than those without anaemia. The relationship between iron deficiency anaemia and pruritus is not well established. To date, only a limited number of studies have attempted to clarify the pathophysiology of this phenomenon, with initial attempts dating back to the 1960s [33]. A study investigating the association between iron deficiency and pruritus severity found that 70 (35%) patients experienced moderate pruritus, while 50 (25%) experienced very severe pruritus, as measured by the VAS scale [34]. A review of the medical records of our patients revealed no evidence of iron deficiency, with the exception of data regarding RBC. Other studies have also found no significant difference between age groups in chronic pruritus in older people [17].

In our study women rated the intensity of pruritus slightly higher than men on the 10-Point Pruritus Severity Scale (10-PSS) and Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), but the differences were not statistically significant. Similar observations can be found in the literature. Studies on the validation of different scales assessing pruritus intensity have shown that age and gender do not significantly influence the intensity of pruritus [14, 35]. Phan et al. observed that men tend to rate itch intensity slightly higher than women [35]. The VAS and NRS have demonstrated high accuracy and concordance in assessing pruritus intensity [35]. Positive correlations were observed between pruritus severity and prevalence with age in both men and women in a study conducted on Chinese patients [36]. This study analysed the severity and prevalence of pruritus in two age groups: under and over 50 years old. However, as previously mentioned, our study did not yield similar results regarding the relationship between pruritus severity and its prevalence with age. We found a strong correlation between all scales (p < 0.001), with the highest correlation observed between VAS and NRS (Figures 2 A–C). The literature also suggests a strong correlation between VAS and NRS [37]. In a validation study of several pruritic scales, it was shown that the numerical rating scale, the verbal rating scale, and the visual analogue scale are valid instruments with good reproducibility and internal consistency in various European countries for different pruritic dermatoses [38].

Bożek and Reich [13] confirmed the validity of the 10-Item Pruritus Severity Scale as a reliable measurement method for assessing pruritus in daily medical practice and research. However, the 10-PSS scale has only been used to evaluate pruritic intensity in patients with pruritic dermatoses. Therefore, there is a lack of data in the literature regarding the use of this scale among the general patient population. When comparing our results to those obtained in the validation process of the scale, we observed that the mean severity of pruritus in individual dermatoses assessed with the 10-item questionnaire was higher than that obtained in our study. The mean total questionnaire score for all patients was 10.4 ±4.5 points, with scores ranging from 3 to 20 points [13]. In our study, the mean result of 10-PSS was 6.22 ±2.35 points, with scores ranging from 2 to 17 points.

Our study confirmed a relationship between medication intake and pruritus. The drugs analysed were antihypertensives, statins, antidiabetic drugs, and opiate analgesics, which were the most commonly used in the study group. The literature suggests that certain drugs have a high potential to cause itching, including antihypertensive drugs such as β-blockers, calcium channel blockers (commonly used in elderly patients), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, thiazides, antidiabetic drugs such as biguanides and sulfonylurea derivatives, statins, salicylates, opiates, psychotropic drugs, antibiotics, and chemotherapeutics [39]. However, we did not find any association between the presence of xerosis and the medications taken. The analysis considered patients who were taking medications known to cause dry skin, such as diuretics, statins, and β-blockers [40]. The use of antipruritic medications (H1-anithistamines) was shown to reduce the possibility of pruritus in another study in a geriatric population [17].

The study has limitations as it is based on a small group of patients. To increase its reliability, the number of patients included in the study should be increased. A complete dermatological diagnosis of the patients should have included a skin biopsy to rule out any previously undetected conditions.

Conclusions

The issue of pruritus should not be underestimated. Many causes of pruritus have been identified, and new ones are still being investigated. Xerosis is one of the most common causes of pruritus. It is essential to provide appropriate education to patients and caregivers on the use of emollients, and therefore the establishment of recommendations would be desirable. To evaluate pruritus in geriatric patients, it is recommended to use standardized questionnaires. It is also advisable to provide education about the pruritic potential of medications, and diagnostic procedures for certain dermatoses. Pruritus may be the only symptom in geriatric patients or may precede the appearance of typical skin lesions for many months. Delayed diagnosis may lead to complications and worsen the prognosis.