Congenital mitral valve defect remains a significant clinical problem in children, especially infants [1]. Due to a lack of commercially available valve prostheses designed for children, expecting their desirable growth, any ineffective repair of the patient’s valve makes it necessary to seek alternative treatment methods [2]. Melody mitral valve replacement (MVR) has been reported as a promising alternative and a bridge to future mechanical MVR in the grown mitral annulus [3].

We present a unique case of a child following infantile Melody surgical-hybrid inverted valve implantation in the mitral position. The child initially presented with recurrent respiratory tract infections which finally led to the late diagnosis of Shone’s syndrome. Recently, the child required replacement of the damaged Melody prosthesis after 1.5 years because of infective endocarditis (IE) during severe pneumonia.

The presented patient was diagnosed at the age of 2 months with critical coarctation of the aorta (CoA) with secondary left ventricular contractility dysfunction, aortic arch hypoplasia, mitral valve dysplasia and regurgitation. Congenital immune disorders and weight deficiency were also observed. Due to severe heart failure, a hybrid treatment strategy was implemented: aortic coarctation angioplasty followed by surgical aortic arch repair with ‘extended end-to-end’ anastomosis. After surgery increasing mitral valve regurgitation was observed.

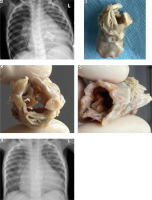

At the age of 6 months, after suboptimal mitral repair, a Melody inverted stent valve was implanted (Melody MVR) in the place of the dysplastic, insufficient mitral valve and dilatated intraoperatively to 16 mm. The child was discharged home with a good result (Figure 1 A).

Figure 1

A – Chest X-ray after Melody valve implantation at the age of 6 months. B–D – Explanted Melody valve ‘on the table’ with signs of infectious degeneration, different angles. E – Chest X-ray after re-Melody MVR

Nearly 1.5 years after the procedure the boy was treated for persistent respiratory infections including chickenpox and severe pneumonia which complicated into sepsis and IE. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed prosthesis severe regurgitation with stenosis.

The child was scheduled for MVR and Melody valve reimplantation in the mitral position (re-Melody MVR) was performed. The prosthesis was removed in its entirety (Figures 1 B–D), and another Melody valve was reimplanted into the mitral orifice and intraoperatively dilatated to 18 mm. No dysfunction, pressure gradient or peri-valvular leakage of the new Melody valve was observed (Figure 1 E).

The postoperative period was complicated by pleural effusion, persistent cough, and periodically elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Viral tests confirmed respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus presence. Clinical improvement was finally achieved after corticosteroid nebulization and general therapy, supported by respiratory physiotherapy. The child was discharged home in a good condition after over 2 months.

The presented technique of Melody valve implantation followed by intraoperative balloon dilatation ensures maximum possible size of the prosthetic mitral orifice area without any harm to the valve structure, and its accuracy. Pediatric Melody MVR was previously described as an alternative method for irreparable mitral valves in children [4], as well as hybrid surgical methods of Melody valve implantation, and in the course of IE [5]. To the best of our knowledge, re-Melody MVR in IE has not been described before, and it is yet another proof of the feasibility of this method, especially in patients with complex congenital heart defects and with concomitant comorbidities. Nevertheless, further efforts are warranted to obtain a proper valvular prosthesis for children with an irreparable mitral valve.