Introduction

Urticaria is a medical condition that is defined by the presence of wheals (hives), angioedema, or both. It is classified based on its duration as acute or chronic. Acute urticaria is defined as the occurrence of symptoms for 6 weeks or less, while chronic urticaria (CU) persists for more than 6 weeks. CU can present with daily or almost daily symptoms or follow an intermittent or recurrent course [1].

The diagnostic evaluation for patients with CU encompasses a comprehensive analysis of their medical history, a complete physical examination, essential laboratory testing, and an evaluation of the condition’s severity, impact, and management. The basic examinations consist of a differential blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or estimated sedimentation rate (ESR), which are conducted on all patients. Total IgE and immunoglobulin G-anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) tests are performed for patients receiving specialist counselling. Additional diagnostic testing may be conducted based on the results obtained from these measurements, if necessary [1].

Food allergy is a potential cause of chronic urticaria, but its role remains debated. Studies have reported varying prevalence rates of food allergy among chronic urticaria patients, with some identifying it as a common cause and others finding it uncommon [2–4]. In cases with a long history of intermittent attacks and severe, generalised symptoms, it is recommended by some experts to investigate IgE-mediated reactions, such as those to α-gal and omega-5 gliadin [5].

Galactose-α-1,3-galactose (α-gal) is an oligosaccharide found on glycoproteins and glycolipids of non-primate mammals, causing an IgE-mediated allergy to mammalian meat [6]. First reported in 2009, α-gal syndrome has been increasingly recognised, particularly in the southeastern United States. The syndrome is commonly triggered by tick bites [7]. Symptoms typically occur 2 to 6 h after consuming mammalian meat or dairy products, varying from general urticaria to anaphylaxis [6]. Because of its delayed onset, diagnosing α-gal allergy can be challenging, and it is sometimes misdiagnosed as recurrent urticaria or idiopathic anaphylaxis. While a recent report postulated that α-gal syndrome might represent a novel cause of chronic urticaria, further research failed to find such an association [8–10]. Nevertheless, in areas where α-gal sensitisation is prevalent, the potential for misdiagnosing cases of α-gal syndrome as chronic urticaria still exists [11].

IgE-mediated allergy to omega-5 gliadin (O5G), a wheat protein, is primarily associated with wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis (WDEIA), where exercise acts as a cofactor. However, O5G allergy manifestations can extend beyond WDEIA, with reactions potentially triggered by non-exercise cofactors or occurring without cofactors. Despite regular wheat ingestion, allergic reactions are infrequent, making diagnosis based on the history alone difficult. Testing for specific IgE to O5G is recommended for patients with exercise-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis, idiopathic anaphylaxis, and recurrent acute (but not chronic) urticaria [12].

The allergy to α-gal and O5G were recently discovered, and physicians’ awareness of these syndromes is limited, what often leads to inadequate patient histories and missed diagnoses [13, 14].

Aim

The aim of this study is to investigate the prevalence of sensitization to α-gal and O5G and its clinical implications in individuals with CU. Our hypothesis suggests that a significant proportion of adult patients with CU are sensitized to α-gal and O5G. Furthermore, we hypothesize that there are demographic, clinical, and laboratory test distinctions among CU patients sensitized to α-gal and O5G when compared to those with CU who are not sensitized to these allergens.

Material and methods

In the non-interventional, observational, and analytical exploratory pilot study conducted in the secondary care hospital allergy department, we studied newly referred adult patients (18 years and older) with CU, characterized by the persistence of wheals (hives), angioedema, or both for more than 6 weeks. These symptoms occurred either daily or almost daily, or followed an intermittent or recurrent course.

Patients were excluded if they had physical urticaria, urticaria associated with connective tissue diseases, or a clear history of food allergies.

Patients were interviewed using a standard diet history tool to support the diagnosis of food allergy [15] and the patient’s blood was collected to assess basic tests recommended by guidelines [1], including differential blood count, CRP, total IgE and anti-TPO and anti-Tg [1]. After reviewing the current literature [5] as part of an audit of our patient cohort with CU, we have routinely started to test tryptase levels, specific IgE to Ascaris lumbricoides, and specific IgE to α-gal and O5G. The α-gal and O5G sensitisation was defined as serum specific-IgE ≥ 0.35 KU/l using the ImmunoCAP™ (ThermoFisher). After reviewing the results, patients’ histories were retaken with specific targeted questions focusing on α-gal and O5G. The oral food and exercise challenge test was conducted only on 1 patient. The oral food challenges in the remaining patients were not performed since they expressed unwillingness to participate in them.

The procedures adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. These guidelines pertain to the medical community and prohibit the disclosure of patient names, initials, or hospital record numbers. Additionally, the procedures were in line with the ethical standards set by the responsible committee on human experimentation, both at the institutional and national level.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of continuous data. Data with a normal distribution are expressed as the arithmetic mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD), while data with an non-normal distribution are presented as the median and range. P-values were calculated using ANOVA for normally distributed quantitative continuous variables and the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney U tests for variables with a non-normal distribution. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 100 patients diagnosed with CU. In the entire CU cohort, there were 71 females and 29 males. 5% (5 patients) of the group exhibited sensitization to α-gal, and 4% (4 patients) showed sensitivity to O5G. In the α-gal sensitised group, 3 (60%) patients were male and 2 (40%) were female. In the O5G-sensitised group, the gender distribution was equal, with 2 (50%) males and 2 (50%) females. Among the patients with CU who were not sensitised to α-gal and O5G, there were 68 (74%) females and 23 (26%) males.

Although the α-gal group had the highest median age (57, with a range of 41–72), compared to the O5G cohort (44, with a range of 19–52) and the non-sensitized cohort (43, with a range of 18–58), this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.1919).

The median levels of specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) were 4.34 kIU/l (range: 0.36–245.1) for α-gal and 9.265 kIU/l (range: 3.48–18.6) for O5G.

Two out of 5 (40%) patients sensitised to α-gal had a convincing history of allergy to red meat. Two of 4 (50%) patients sensitised to O5G had a convincing history of allergy to wheat, and in both cases, it was exercise-induced. The specific information on the α-gal-sensitised cohort can be found in Table 1, whereas the specifics about the O5G cohort are provided in Table 2.

Table 1

Characteristics of patients sensitised to α-gal (specific immunoglobulin E > 0.35 kIU/l)

Table 2

Characteristics of patients sensitised to omega-5-gliadin (specific immunoglobulin E > 0.35 kIU/l)

One male patient was sensitised to both α-gal and O5G, and he successfully passed the exercise challenge test with gluten without any reaction.

In the α-gal-sensitised group, 3 (60%) patients also had angioedema; however, in the O5G-sensitised group, 1 (25%) patient experienced angioedema. Among the patients without sensitisation to α-gal or O5G, 51 (56%) had angioedema. Additionally, 3 (3%) patients in the non-sensitised group had gastrointestinal problems, whereas no patients in the α-gal-sensitised or O5G-sensitised groups reported such issues.

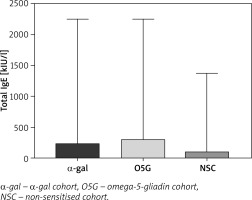

The quantitative differences among the three groups were analysed and shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in most variables, except for total IgE levels and specific IgE levels to Ascaris lumbricoides. The total IgE levels were significantly (p = 0.0392) lower in the group without sensitisation (median: 104 kIU/l, 3–1374), compared to α-gal (median: 228 kIU/l, range: 62–2246) and O5G group (median: 301 kIU/l, range: 155–2246) (Figure 1), and levels of specific IgE to Ascaris lumbricoides in α-gal cohort were significantly (p = 0.0021) higher (0.3 kIU/l, range: 0.07–1.41) than in non-sensitised cohort (0.01, range: 0–2.8 kIU/l).

Table 3

Laboratory blood tests of the whole cohort and its sub-cohorts (α-gal-sensitive, omega-5-gliadin-sensitive, and cohort without sensitisation to α-gal and omega-5-gliadin)

[i] Values for tryptase are presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data. All other parameters are presented as median (range) for non-normally distributed data. The p-values were calculated using ANOVA for normally distributed variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study identified low prevalence of sensitisation and clinically overt allergy to α-gal and O5G in a cohort of patients with CU. Although these prevalence rates are low, it is clinically significant for these patients. Even a tiny percentage of patients with undiagnosed sensitisation can benefit significantly from targeted diagnosis and treatment, underscoring the need for awareness and testing. Previous studies have reported varying prevalence rates, highlighting the importance of considering regional and demographic factors in sensitisation patterns [8–12, 16].

The total IgE levels were highest in the sensitised groups, suggesting that elevated total IgE could be a marker for specific allergen sensitisation in CU patients. However, it could also result from multiple sensitisations and cross-reactivity without clinical relevance. We noticed that patients with a convincing food allergy history had a higher ratio of specific IgE to total IgE than patients without a convincing food allergy history (Tables 1 and 2). This ratio appears to be a better marker of food allergy than the absolute values of specific IgE and total IgE.

The gender distribution in our study revealed a predominance of females in the overall CU cohort (71%), consistent with general CU demographics [17]. However, the sensitised subgroups showed a different pattern. The α-gal-sensitised group had a higher proportion of males (60%), which aligns with the existing literature suggesting a higher prevalence of α-gal sensitisation among males, possibly due to increased exposure to tick bites [18]. The O5G group showed an equal gender distribution in sensitisation. However, only females had convincing allergy, indicating gender predisposition in this subgroup, while other studies found a higher prevalence in males [12, 19].

Less than half of patients with α-gal sensitisation had a well-supported history of red meat allergy, while the proportion of patients with a well-supported wheat allergy was somewhat higher in the O5G-sensitised group. However, just 1 patient underwent a food challenge test. Hence, we cannot ascertain the results for the remaining individuals.

The prevalence of angioedema between the α-gal-sensitised and non-sensitised groups was not significantly different, suggesting that angioedema may not be a distinguishing factor between patients with α-gal sensitisation and those without it. However, these findings reaffirm the well-established strong association between α-gal sensitisation and angioedema [20]. Additionally, angioedema was notably less common in the O5G group. However, it is important to note that the number of patients within α-gal and O5G groups were small, limiting the ability to draw definitive conclusions. As a result, the role of angioedema in distinguishing between these sensitisation groups remains inconclusive. Gastrointestinal problems were absent in the α-gal and O5G but present in 3% of the non-sensitised cohort, suggesting that gastrointestinal symptoms may not be a key feature of these specific food sensitivities and allergies.

A recent study [21] discovered a positive correlation between anti-α-gal-specific IgE and Ascaris lumbricoides–specific IgE in the serum of individuals with α-gal allergy. Additionally, multiple α-gal-containing glycoproteins were identified in the intestines of Ascaris lumbricoides. Additionally, upon exposure to non-α-gal-containing Ascaris lumbricoides antigens, RS-ATL8 IgE reporter cells, primed with serum from individuals with α-gal allergy, exhibited a notable activation of basophil luciferase signal compared to controls without allergies. These findings suggest a potential link between exposure to Ascaris lumbricoides and the development of α-gal sensitisation and clinical reactions [21].

Our findings are in line with the outcomes of the previous study [21]; individuals in our α-gal group exhibited higher levels of specific IgE to Ascaris lumbricoides than those without α-gal sensitisation. Although the medians of both groups were below the levels that are usually considered a sign of sensitization to Ascaris.

However, our study has several limitations, including a relatively small sample size and the lack of oral food challenges in sensitised groups and a control group without urticaria. Future research should focus on larger, more diverse cohorts to validate our findings and explore the underlying mechanisms of sensitisation. Longitudinal studies are also needed to assess the long-term outcomes of sensitised CU patients and the effectiveness of targeted interventions.

Due to the relatively low prevalence, routine screening for α-gal and omega-5 gliadin sensitisation and allergy in CU patients may not be warranted. However, targeted testing of patients with severe, recurrent, or atypical symptoms could improve diagnosis and management. Our findings support the need for heightened clinical awareness and consideration of these allergens in the differential diagnosis of CU, particularly in regions with known tick exposure or high wheat consumption.