Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, present a significant challenge to healthcare due to their chronic nature and debilitating symptoms [1–3]. A significant number of patients who experience a primary or secondary loss of response to dedicated medicines raises concerns, especially in the era of biological therapy [4]. While pharmacotherapy remains the primary treatment strategy, growing interest has emerged in lifestyle modifications, including physical activity (PA), in managing these conditions [5, 6]. However, there is still a lack of full understanding of the effectiveness of PA and how it can be best integrated into the current treatment options. This review aims to explore and compile existing research on the impact of structured exercise on IBD. We will delve into various studies conducted in this field, scrutinizing the effects of exercise programs on the disease’s course, patients’ quality of life, IBD-related fatigue, body composition, bone mineral density, muscular function, and inflammatory response. Additionally, the study aims to identify gaps in the current body of knowledge, thereby providing a roadmap for the development of evidence-based exercise guidelines for individuals with IBD.

Our goal is to supply a comprehensive overview that could guide future research and inform clinical practice incorporating structured exercise as a potential adjunct therapy for IBD.

Methods

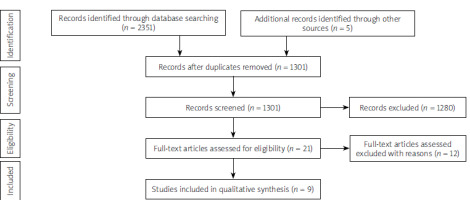

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was used as a framework to conduct the literature search [7]. The search process and the final study selection are shown in the diagram (Figure 1).

Literature preview

Electronic databases from January 2000 to December 2023 were searched: Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, and Scopus, to identify suitable articles. The Boolean search method was applied. We have reviewed the reference lists of studies involved for more citations, to identify other trials. The full texts of the studies were screened, and any duplicates were eliminated. The author, institution, and publication source of the study were known to the review authors.

Study selection

Studies that examined the impact of structured exercise, including randomized controlled trials, pilot studies, observational studies, case-control, or cross-sectional studies, were incorporated into the analysis. Only research conducted in English and concentrating on adults aged over 18 years with IBD was taken into consideration. Studies were limited concerning the year of publication and type of exercise intervention. Complex intervention or lack of PA intervention was the basis for exclusion. Table I encompasses all the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table I

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data extraction

Due to the complex nature of IBD, including its phenotype, location, disease activity, and treatment forms, as well as the heterogeneity of the study designs and interventions and the lack of consistency in outcome measures, our research was made using only a qualitative approach.

The disease’s course

Exercise status is a potential environmental factor in disease activity and there is an ongoing scientific debate about whether PA influences the induction and/or the maintenance of remission. There is a growing body of evidence that exercise training is a safe management tool [8–10]. During the exercise intervention established by Cronin et al. [8] (moderate-intensity aerobic and resistance exercise in quiescent IBD) none of the patients showed a decline in their disease activity scores. After 8 weeks of exercise, the disease activity scores of the participants continued to be low, and no individual was excluded from the study due to an exacerbation of symptoms [8]. Similar results were observed in patients with mild to moderate IBD after a 10-week moderate-intensity running program [9] and in patients with quiescent or mildly active Crohn’s disease undergoing moderate endurance and muscle training [11]. Some concerns arose from the findings of Lamers et al. [12]. The study revealed that Patient Harvey Bradshaw Index (P-HBI) scores increased more in CD patients who walked compared to those who did not (mean change between groups 95% CI 3.5 (0.1–6.9); p = 0.046), indicating a potential escalation in clinical disease activity during PA. However, these changes were not mirrored in fecal calprotectin (FCP) levels, whereas colonic disease was the case for most of the CD patient group. Authors conclude that the likelihood of an exercise-induced increase in clinical disease activity is minimal, given that FCP is a more accurate indicator of endoscopic disease activity than clinical disease activity questionnaires [12]. In the same study clinical disease activity did not change in the walkers with ulcerative colitis [12]. There is a lack of large prospective studies examining the association between exercise and disease activity in patients with moderate and severe courses of IBD.

Quality of life (QoL)

Patient-reported outcomes are nowadays one of the priorities in the management of IBD. The physical and psychological well-being of individuals with IBD may be impaired due to burdensome symptoms and chronic, relapsing-remitting course of the disease. Although PA is one of the strategies to improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [10, 13, 14], the evidence from RCTs on the effect of PA (including type and intensity of PA) is limited [9, 10, 15]. Wiestler et al. [13] in the cross-sectional study measured habitual PA with accelerometry in IBD patients and revealed a positive correlation between PA and HRQoL. Another observational research, conducted in a Dutch cohort, proved the positive impact of an individualized exercise program on the QoL of patients; IBD Questionnaire (IBDQ) total score of 156 (±21) increased to 176 (±19) (p < 0.001) [14]. Upon examining the various aspects of HRQoL, there was a significant improvement in the areas of emotional, systemic, and social functioning [14]. When Jones et al. [15] studied combined impact and resistance training in adults with stable Crohn’s disease, they observed a positive change in HRQoL. Using the IBDQ total score, the exercise group improved at 3 months (adjusted mean difference 17, 95% CI: 7–26; p = 0.001) [15]. This improvement was noticeable also with EQ-5D utility index, which was superior in the exercise group at both 3 and 6 months (adjusted mean differences 0.117 [95% CI: 0.023–0.211, p = 0.016] and 0.109 [95% CI: 0.038–0.181, p = 0.004], respectively) [15]. The above research is in agreement with the findings of Klare et al. [9]. HRQoL, reported as the IBDQ total score, improved by 19% in the group with the 10-week physical exercise program, compared with an 8% improvement in the control group [9]. The results of the study with high-intensity interval training are also consistent [10], making moderate-intensity interventions even more permissible. Moreover, Cronin et al. [8] showed that in physically unfit patients with quiescent IBD, moderate-intensity combined aerobic and resistance training is safe. However, the 8-week activity program revealed no statistically significant differences in QoL measurements (SF36®V2) or mood and anxiety evaluations (The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – HADS, The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – STAI, The Beck Depression Inventory-II – BDI-II) when comparing the control and the intervention groups [8].

Fatigue

Fatigue is a prevalent and debilitating symptom that can significantly hinder the daily activities and overall well-being of individuals with IBD. There is a paucity of high-quality research on fatigue-reducing interventions in that patient group. Yet, no strong recommendations for IBD-related fatigue management are established. In the British RCT [15], combined impact and resistance training in adults with stable Crohn’s disease diminished fatigue (IBD-F score) in the exercise group at 6 months (adjusted mean difference –2, 95% CI: –4 to –1; p = 0.005), but not at 3 months (adjusted mean difference –1, 95% CI: –3 to 1; p = 0.249). On the other hand, van Erp et al. [14] conducted a pilot observational study with IBD patients in remission and severe fatigue and tested personalized 12-week resistance training. The exercise program led to a significant reduction in fatigue, with scores on the checklist individual strength (CIS) from 105 (±17) to 66 (±20) (p < 0.001) and a significant decrease in the severity of fatigue (CIS-F) score from 49 (±4.7) to 29 (±8.9) (p < 0.001) was observed [14].

Body composition, bone mineral density, and muscular function

IBD for a long time has been connected not only with impaired QoL and fatigue but also with malnutrition and sarcopenia. As the prevalence of obesity increases worldwide, the number of overweight patients with IBD becomes more significant. In the era of co-occurrence of obesity and malnutrition, improvement of long-term body composition is crucial for enhancing overall health outcomes. Participants of the Irish randomized controlled cross-over trial [8] experienced favorable changes after 8 weeks of combined aerobic and resistance training. A median (IQR) 2.1% (–2.15, –0.45) decrease in total percentage body fat was observed, compared to a median gain of 0.1% (–0.4, 1) body fat in the control group (p = 0.022) [8]. At the same time, there was a median increase of 1.59 kg (0.68, 2.69) in total lean tissue mass in the exercise group, in contrast to a median decrease of 1.38 kg (–2.45, 0.26) in the control group (p = 0.003) [8]. Jones et al. [15] studied combined impact and resistance training in adults with stable Crohn’s disease. They identified significant improvements in the lumbar spine bone mineral density (adjusted mean difference 0.036 g/cm2; 95% CI: 0.024–0.048; p < 0.001) following a 6-month exercise intervention [15]. What is more, the study reported significant enhancements in both upper and lower limb muscular endurance (p < 0.001), quantified using the 30-s bicep curl test and 30-s chair stand test [15]. Similarly, a German randomized study shows that in Crohn’s disease patients, the maximal and average strength in the upper and lower extremities increased significantly after 3 months of moderate endurance or muscle training [11].

Inflammatory response

Although the exact molecular mechanisms by which PA modulates inflammatory pathways are still not fully understood, the beneficial effect of PA on the inflammatory response in IBD patients is now suggested by researchers [6, 16, 17].

Considering IBD exercise studies involving patients with mild or inactive disease [8, 9, 11], the infrequent observation of statistically significant alterations in biomarkers following exercise is expected. In most research that investigated the impact of exercise on C-reactive protein and FCP, the interventions studied did not yield any significant improvement [8, 9, 11, 12]. After a ten-week moderate-intensity running program in patients with mild to moderate IBD, a statistically significant decrease in leukocyte counts was observed in the intervention group (7.0 ±2.2 vs. 5.6 ±1.5, p = 0.016) with no deterioration in the hemoglobin level [9]. Studies in which pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-8, IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α) were taken into account suggest that the disease remained stable with exercise [8, 12]. Lamers et al. observed IL-6 and IL-10 transient increase in both IBD patients and non-IBD controls between baseline and post-exercise day one, without any deterioration in disease activity [12]. That may be attributed to the body’s adaptation to training, indicating a significant surge in the production and secretion of myokines, which are predominantly regulated by skeletal muscles [18, 19]. Spijkerman et al. [20] assessed the reactivity of granulocytes and monocytes to the bacterial/mitochondrial stimulus N-Formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF) in individuals with IBD and healthy controls participating in a four-day walking test. After 3 days of exercise, an enhanced reaction of neutrophils and monocytes to fMLF was observed [20]. Notably, the exercise correlated with less responsiveness of both neutrophils and monocytes in patients with IBD. The authors concluded that less responsive leukocytes could potentially lead to reduced inflammation in the intestine, offering a possible explanation for the reduction in flare-ups in IBD patients following regular exercise [20].

Conclusions

The already available research results are promising in terms of effectiveness and safety of the structured exercise programs and trial procedures. However, the heterogeneity of the study designs, interventions, limited number of participants, and lack of long-term follow-up render the advantages of PA ambiguous, requiring interpretation of these outcomes through careful consideration. Therefore, more rigorous, and standardized trials are needed to establish the optimal type, intensity, frequency, and duration of exercise for IBD patients, as well as to explore the underlying mechanisms and mediators of the exercise-induced benefits. The association between structured exercise and disease activity in patients with moderate and severe IBD has not been examined by large prospective studies. Novel investigations of non-invasive measures of inflammation may help quantify the intensity and duration of exercise, increasing research safety. Assessment of the cost-effectiveness and feasibility of structured exercise programs in real-world settings is essential. Exploring successful strategies for integrating exercise into the multidisciplinary care of IBD patients and identifying effective methods to enhance adherence among this population could be the next avenue for future research.