Introduction

Treatment algorithms for patients with metastatic prostate cancer have changed as a result of studies that demonstrated how early treatment intensification in the hormone-sensitive phase improves overall survival and other endpoints [1–6]. These changes are summarized in recent guidelines [7, 8]. Despite better outcomes, development of metastatic castration-resistant disease (MCRPC) is still common. When moving established MCRPC treatments forward to the earlier hormone-sensitive phase, an important question arises: is re-exposure after a time period on a different regimen a reasonable option? In our healthcare setting with close adherence to national guidelines and centralized drug price negotiations, the first MCRPC drug that was introduced in the earlier hormone-sensitive phase was docetaxel [9]. Its utilization in our hospital started in 2014 in patients with de novo, hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer after publication of the practice-changing CHAARTED study [1]. In the beginning, we offered early docetaxel to patients with high-volume disease who did not present with contraindications. Subsequently, selected patients with extensive lymph node metastases outside of the pelvis in the absence of bone or other metastases also received early docetaxel.

After diagnosis of MCRPC, several factors influence the choice of first-line therapy, e.g. comorbidity, organ function, frailty, previous therapy and patient preference. Options include docetaxel, abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide [10, 11], and later on also cabazitaxel, Ra-223, other radioligands and PARP inhibitors (depending on genetic alterations) [12, 13]. We focused the present study on docetaxel-eligible patients and analyzed numerous treatment-related parameters (pre-exposure, dosing, line, etc.) and patient- disease-related parameters (age, blood test results, extent of disease, etc.) to identify prognostic factors for overall survival and compare these to studies from other healthcare settings.

Material and methods

A retrospective study was performed, which included 132 consecutive men (all Caucasian) with MCRPC who received oncology care at Nordland Hospital Trust’s hospital in Bodø (academic teaching hospital in rural North Norway) between 2009 and 2022. A previously described, continuously updated quality-of-care database with data extracted from regional electronic health records was employed [9, 14]. Treatment was given according to national guidelines, outside of prospective clinical trials (a so-called real- world cohort). A local multidisciplinary team provided guidance and all patients were also discussed during regular oncology team meetings. We used traditional staging methods, such as radionuclide bone scan, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, rather than routine positron emission tomography. Histological verification was obtained on a case-by-case basis, e.g. in liver metastases without simultaneous bone metastases. A minority of patients had no histological verification at all (prostate-specific antigen – PSA, and imaging-based prostate cancer diagnosis). Blood tests were taken at most one week before the start of chemotherapy. In all cases, systemic treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT; goserelin, degarelix or orchiectomy) was employed as backbone treatment. In line with previous national guidelines, enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate was never instituted for hormone-sensitive disease in this cohort. Early docetaxel was administered according to the CHAARTED protocol, i.e. every 3 weeks for 6 cycles (75 mg/m2). In the MCRPC setting, the same 3-week regimen was employed, together with prednisolone, or if poor tolerance was anticipated, one of two low-dose alternatives: weekly or every other week. The weekly regimen was prescribed to patients with performance status (PS) 2, very elderly patients, or those with a high burden of comorbidity. Only patients with PS 0–2 and appropriate bone marrow function received docetaxel. The number of cycles was not specified a priori, but rather adjusted to tolerance and effect. Docetaxel holidays were provided as needed. Sequential lines of further treatment included abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide, cabazitaxel or Ra-223. The recently introduced targeted radioligands and PARP inhibitors were not yet available in the time period studied here.

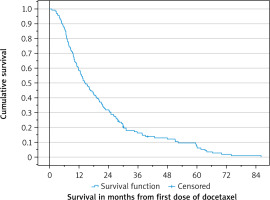

Actuarial survival from the day of docetaxel initiation and from cancer diagnosis was calculated with the Kaplan- Meier method and compared between subgroups with the log-rank test. Three patients were censored at the time of their last follow-up (minimum 28 months, median 30 months). Date of death was recorded in all other patients. Associations between different variables of interest were assessed with the χ2 or Fisher’s exact probability test (two-tailed). The impact of continuous variables such as age and blood test results on survival was examined in univariate Cox analyses. A multivariate forward conditional Cox analysis of prognostic factors for survival was then performed. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The median age was 72 years, range 56–86 years. The corresponding figures at first cancer diagnosis were 65 and 49–84 years. The majority of patients progressed from initially non-metastatic disease. Forty-six (35%) had distant metastases already when diagnosed with prostate cancer. Among patients with metachronous disease, 43 had initial high-risk cancer, 20 intermediate or low-risk cancer, and 20 N1 disease. Initial management included prostatectomy in 24 and radical radiotherapy in 17 patients. The most common pattern of metastases was bone alone (39%). Median PSA was 30 µg/l at first cancer diagnosis, 61 µg/l at detection of metastatic disease and 109 µg/l at start of docetaxel for MCRPC. Further patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The blood test results are shown in Table 2. Only one patient had albumin below the lower limit of normal. Other tests such as liver enzymes and creatinine were not recorded in the database.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics (n = 132): androgen deprivation therapy + docetaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; time period 2009–2022

Treatment details

In this elderly cohort, weekly low-dose docetaxel was the preferred regimen (44%). Seventy-three percent were treated in the first line, i.e. had not received other drugs for MCRPC before docetaxel. The remaining patients had received first-line abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide. Eleven patients (8%) were pre-exposed to docetaxel in the hormone-sensitive phase. Concomitant bone-targeting agents were given to 50 patients (38%), mostly zoledronic acid. Disease progression was the prevailing cause of docetaxel discontinuation. Subsequent cabazitaxel was administered in 16 patients (12%). Other patients received abiraterone acetate n = 25 (19%), enzalutamide n = 13 (10%) or both drugs n = 24 (18%) after docetaxel. Another 14 patients (11%) received Ra-223. Ra-223 before docetaxel was rarely employed (7.5%).

Overall survival

Median survival was 14.3 (95% CI: 11.3–17.3) months (Fig. 1). Corresponding figures from cancer diagnosis were 69.8 (57.0–82.6) months (37.7 in case of de novo metastatic disease, 95% CI: 27.4–48.0).

Univariate analyses

Age and comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, previous other cancer, cardiac disease, etc., were not associated with survival from start of docetaxel. However, the number of prescription drugs for comorbidities was significant, as shown in Table 1. Furthermore, patterns of spread were linked to survival (worse if visceral metastases were present, best if lymph node metastases alone were treated). In addition, blood test results predicted survival. Lower hemoglobin, higher C-reactive protein (CRP), higher alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and higher lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) indicated shorter survival. The association between higher PSA and shorter survival was weaker, p = 0.06. Among treatment-related factors, dosing regimen (every 3 weeks best) and first-line docetaxel emerged as significant factors, whereas pre-exposure in the hormone-sensitive setting did not (p = 0.76). Regarding subsequent drug treatment, survival was longest in patients exposed sequentially to both abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide (median 37.7 months) and those who received Ra-223 (median 34.6 months). Survival was shortest in patients who finished systemic therapy immediately after docetaxel (median 10.0 months).

Multivariate analysis

Except for subsequent treatment (a variable that is impossible to account for at the start of docetaxel when response and future decisions are unpredictable), all other parameters with p-values < 0.1 in univariate analyses were included in the multivariate Cox regression model. The latter showed highly significant p-values for hemoglobin and LDH as the most important prognostic factors (Table 3).

Table 3

Prognostic factors for overall survival in uni- and multivariate analyses

Discussion

In this observational single-institution study from rural Norway, the median overall survival of patients treated with docetaxel for MCRPC was 14.3 months. No significant influence of previous exposure to the drug in the hormone-sensitive phase was detected; however, surprisingly few patients (n = 11) were treated after pre-exposure. This small number likely reflects the relatively long survival without progression to MCRPC obtained with early docetaxel. Vale et al. performed a meta-analysis of the STAMPEDE, CHAARTED and GETUG-15 trials, i.e. early docetaxel studies [15]. The hazard ratio (HR) of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.68–0.87; p < 0.0001) translated to an absolute improvement in 4-year survival of 9% (95% CI: 5–14) for docetaxel plus ADT. In addition, utilization of first-line MCRPC alternatives such as abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide may have prolonged the time to docetaxel re-exposure in our total patient population, including men who were not (yet) eligible for the present study. We have only recently started to offer both docetaxel and abiraterone acetate in the hormone-sensitive phase, meaning that the present cohort includes patients managed before that transition.

Docetaxel has been used in the MCRPC setting for approximately 20 years since publication of the seminal TAX 327 data [16]. Australian researchers have studied 753 men with MCRPC and looked at a large number of endpoints including time to treatment failure (TTF), overall survival, PSA50 response rate and adverse events of special interest (AESI) [17]. Fifty-seven percent of men were aged < 75 years, 31% 75–85 years and 12% > 85 years. With increasing age, patients were more likely to receive androgen receptor signaling inhibitors as initial therapy. PSA50 response rates or TTF did not significantly differ between age groups for chemotherapy or androgen receptor signaling inhibitors. Prostate-specific antigen doubling time > 3 months was an independent positive prognostic factor for patients receiving any systemic therapy. This parameter was not available in our database. Older Australian patients who received docetaxel were more likely to experience AESI (18% in < 75 years vs. 37% in intermediate vs. 33% in > 85 years, p = 0.038) and to stop treatment as a result.

In a large international registry, first-line MCRPC therapy with docetaxel led to a median survival of 27.9 months [18]. In our own rural and elderly cohort only 17.3 months was recorded (21.3 if the 3-week schedule was employed). According to US SEER-Medicare data (2007–2019) median survival from the start of first-line treatment (docetaxel or other drugs) for MCRPC was 21.5 months [19]. In a large French docetaxel cohort median survival was 20.3 months [20]. Overall, our own data illustrate that rural cancer care often results in inferior outcomes, caused by different sociodemographic factors. In many countries, rural populations tend to be older, have lower educational attainment, and lower household income compared with people from non-rural regions [21]. The prevalence of poor health, health-related unemployment, tobacco smoking, and physical inactivity was statistically significantly higher in rural compared with urban American cancer survivors [22]. A large Swedish study of MCRPC showed that, despite treatment availability, treatment utilization remained low. Docetaxel was used in 39%, abiraterone acetate in 15%, enzalutamide in 13%, cabazitaxel in 11% and Ra-223 in 5% of treatments. Treatment increased from 22% in 2006–2009 to 50% in 2013–2015 (p < 0.001) [23].

A recent meta-analysis included 22 studies [24]. In MCRPC patients treated with docetaxel, subsequent treatment with cabazitaxel was associated with better survival compared to that without cabazitaxel (pooled HR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.56–0.89). In the cabazitaxel group, several pretreatment clinical features and blood tests were associated with worse survival: poor PS, presence of visceral metastasis, symptomatic disease, high PSA, high ALP, high LDH, high CRP, low albumin and low hemoglobin. Chi et al. suggested a prognostic index predicting overall survival in patients with MCRPC treated with abiraterone acetate after docetaxel [25]. Six risk factors individually associated with poor prognosis were included in the final model: PS, LDH, presence of liver metastases, albumin, ALP and time from start of initial ADT to start of treatment (≤ 36 months). Patients were categorized into good, intermediate and poor prognosis groups based on the number of risk factors. Pinart et al. analyzed 12 studies that had developed prognostic models including 8750 patients with MCRPC aged 42–95 years [26]. Models included 4–11 predictor variables, mostly PS, hemoglobin, PSA, ALP and LDH. Model performance after internal validation showed similar discrimination power, in the range 0.62–0.73. Overall survival models were constructed as nomograms or risk groups. We found in addition that a surrogate of overall comorbidity, i.e. number of drugs, was associated with survival, together with blood test results, which mirror overall disease burden (hemoglobin, LDH, and with weaker evidence (p > 0.05) CRP and PSA).

Limitations of the present study include the number of patients, statistical power of subgroup analyses, and retrospective design. Unfortunately, numerous patient records did not include information about PS, which therefore was not included in the study. The clinicians selected patients with contraindications for docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for other, less efficacious dosing regimens, leading to differences in baseline factors that probably were not completely accounted for in multivariate analysis. Comparable bias may have influenced the timing of docetaxel (first or later lines). These factors may also explain the favorable survival after docetaxel followed by two sequential androgen receptor signaling inhibitors. We did not collect data on treatment intensity and duration, toxicity, PSA response and time to progression.

Conclusions

In this rural health care setting, survival after docetaxel was shorter than reported by other groups. Blood test results were confirmed as important prognostic factors. In the present era of changing treatment sequences, monitoring of treatment results and comparison to those from clinical trials is recommended.