Introduction

The Cox MAZE IV is the gold standard for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF) [1, 2]. However, since its introduction, many variations in the number and location of individual lesions and in the form of supplied energy have been described [3]. Cryoenergy, along with radio-frequency energy, is the most commonly used method of lesion formation in patients after surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation, with good and stable long-term results [4–6]. Despite frequent use, the clinical effect of cryoenergy in the endocardial and epicardial approaches is not sufficiently known. For these reasons, surgeons sometimes refuse to simultaneously add surgical ablation of AF to the main surgery. In clinical practice, many patients attending cardiac surgery with AF are not treated at all (up to 50%) [7].

Aim

The aim of this study was to compare the clinical effect of various cryoenergy applications on the postoperative incidence of sinus rhythm and the completeness of lesions performed.

Material and methods

This was a single-centre, prospective study. A total of 55 patients underwent surgical ablation of AF as part of another cardiac surgery procedure (myocardial revascularisation, valve surgery, combined procedure). Before the start of the study the authors obtained approval from the institutional Ethical Committee regarding the study design. The selection criteria were: AF refractory to at least one class I or class III antiarrhythmic therapy, concomitant cardiac surgery, absence of prior catheter ablation, and written, informed consent to study participation and postoperative electrophysiological examination. The standard surgical ablation protocol includes the isolation of the pulmonary veins and the formation of a box lesion by cryoenergy under various conditions – epicardially on extracorporeal circulation and cardiac arrest, epicardial on extracorporeal circulation on the beating heart, and endocardial. A Cardioblate® CryoFlex® surgical ablation probe, Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA was used to create the lesion. The standard duration of cryoenergy application was 2 minutes at –160°C. The electrical insulation of the lesions was not electrically verified during the operation. All of the patients underwent left atrial appendage occlusion using an Atriclip device. In the postoperative period, treatment of AF was as follows: all patients were on anticoagulant therapy with warfarin for 3 months. If they had AF during the postoperative period, they were pharmacologically treated with Cordarone or electroconversion, and patients were given oral Cordarone for 1 month after surgery. During the postoperative period, patients were invited to attend an electrophysiological examination to assess the completeness of surgical ablation lesions and, if necessary, to supplement the lesions with catheter ablation. All catheterisation procedures were performed using the CARTO3 mapping system. None of the patients was on anti-arrhythmic therapy during electrophysiological examination. If a normal sinus rhythm was present at the beginning of the procedure, RF ablation of the cavotricuspid isthmus was performed prior to initiation of left atrial ablation. The achievement of a bidirectional block of conduction through the isthmus was determined by standard criteria. Then, after double trans-septal punctures, two controllable trans-septal sheaths (8F, Channel, BARD Electrophysiology, Lowell, MA, USA) were introduced into the left atrium (LA), and a virtual anatomy reconstruction was performed, and a bipolar voltage map obtained at least 300 points for detailed mapping of the whole LA. A circular mapping catheter (LASSO®, Biosense Webster, Inc., Diamond Bar, CA, USA) was used in all veins to confirm isolation or electrical reconnection. RF energy was applied using a ThermoCool® Smart Touch™ catheter with a 3.5 mm irrigated tip (Biosense Webster, Inc.) and a software module that allows contact force sensing with a temperature limitation of 44°C and radio-frequency energy of up to 35 W. After reaching the insulation of all the veins (if they were reconnected), the posterior wall of the LA was mapped to confirm electrical insulation. For this purpose, the Lasso catheter was positioned so as to be perpendicular to the posterior wall. If no potentials were noted, the box lesion was considered present. If any potential was noted, both superior and inferior connecting lines were mapped to look for a gap. All gaps were subsequently ablated. Data were collected from the hospital medical electronic system and during postoperative controls by patients’ surgeons.

Results

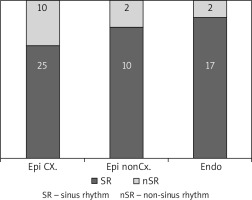

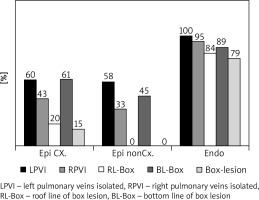

Twenty-four patients underwent epicardial ablation on the arrested heart (group 1), 12 patients underwent epicardial ablation on the beating heart (group 2), and 19 patients underwent endocardial ablation (group 3), as shown in Table I. The interval between cardiac surgery and electrophysiological examination was 144 ±138 days (group 1) vs. 178 ±84 days (group 2) vs. 102 ±76 days (group 3). During electrophysiological examination (Table II), sinus rhythm was present in 71% of patients 83% vs. 89% of patients in the groups 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 1). The completeness of pulmonary vein isolation was confirmed in 31% vs. 25% vs. 95% of patients and complete box lesion in 15% vs. 0% vs. 79% of patients, in the groups 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Figure 2).

Table I

Perioperative variables

Table II

Findings during the electrophysiology examination

Discussion

In the past, several articles were published dealing with the use of cryoenergy from the epicardial and endocardial approaches [6–16]. However, these studies were performed under laboratory conditions in an animal model, and the results were evaluated histologically in the acute phase of healing. Our work brings results from clinical practice, in which the structure of the left atrial wall is influenced by ongoing AF and the results of surgical ablation are evaluated electrophysiologically and along the entire length of the ablation line. There is also some time to create the scar after surgical ablation. This is one of the most accurate ways to evaluate the success of surgical ablation. According to available US registries, cryoenergy is used in approximately 30–50% of patients undergoing concomitant surgical ablation primarily from the epicardial approach [17].

Use of cryoenergy from the endocardial approach is an established method that encounters several obstacles: in patients without mitral and tricuspid valve defects, bicaval cannulation and opening on the left and right atria is necessary. This results in prolonged cardiac arrest interval, and a risk of air embolisation and postoperative bleeding. For these reasons, surgeons sometimes refuse to simultaneously add surgical ablation of AF to the main control. In clinical practice, many patients attending cardiac surgery with AF are not treated at all – up to 50% [17].

Our work also shows that the clinical effect of surgical ablation in terms of maintaining sinus rhythm in the postoperative period may not be identified with the completeness of surgical lesions. The incompleteness of surgical lesions may lead to a lower incidence of sinus rhythm in the postoperative period, and individual gaps in surgical lesions may have more proarrhythmogenic potential [18–20].

The limitations of this study are particularly evident in a small number of patients. However, our results may indicate a direction for further research into the surgical use of cryoenergy.

Conclusions

Despite the similar clinical effect of surgical ablation in all three approaches, the most electrophysiologically effective use of cryoenergy is endocardial ablation. This approach has a very good result. Our finding further supports the endocardial use of cryoenergy during surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation, and the results of this local study have led to changes in our workplace practices.