Introduction

Dysmenorrhea consists of painful cramps, occurs before the monthly menstrual flow, and lasts for a short period of time after [1]. Dysmenorrhea is usually associated with other symptoms (including vomiting, insomnia, and irritability) [2].

Dysmenorrhea is one of the common complaints in gynecology [1, 2]. Dysmenorrhea affects 16–91% of reproductive-age women, and 80% of adolescents [1, 2].

Primary dysmenorrhea occurs in the absence of any pelvic abnormalities and/or pelvic lesion(s), while secondary dysmenorrhea is usually associated with pelvic pathologies (i.e., endometriosis and/or adenomyosis) [1–3].

Dysmenorrhea occurs following increased uterine prostaglandins, and leukotrienes, which lead to increased uterine contractility and/or ischemia [3–5].

Dysmenorrhea negatively affects the quality of life (QoL) [6]. A meta-analysis found that underweight participants were at greater risk of primary dysmenorrhea [7].

Comparative research found that women with > 27.5 kg/m2 body mass index (BMI) had significantly increased risk of dysmenorrhea compared to normal controls [8]. Increased odds of dysmenorrhea were reported in underweight and obese participants [9].

The previous research results regarding primary dysmenorrhea and its relation to BMI are inconsistent and controversial [7].

The younger generation’s QoL and the early treatment of diseases are crucial goals in the Republic of Kazakhstan [10]. Therefore, this research was designed to assess the relation between primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and BMI.

Material and methods

Two-hundred and ten adolescents were recruited for this cross-sectional research to assess the relation between primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and BMI.

Participants were included in the current research after West Kazakhstan Marat Ospanov Medical University (WKMU) approval, and consent from the participants themselves, and their guardians following the Helsinki Declaration.

After thorough evaluation including thorough history, and measurement of the participants’ weight, height, and BMI, pelvic sonography was performed for the studied adolescents to rule out any pelvic abnormalities and/or lesion(s) using the Samsung HS40 ultrasound machine (Samsung Co., Korea).

Inclusion criteria include adolescents (12–18 years old), with regular cyclic menstrual flow, and primary dysmenorrhea of more than one year.

Exclusion criteria include adolescents less than 12 years old or more than 18 years old, adolescents with pelvic abnormalities (including urinary and/or genital tract abnormalities), pelvic lesion(s) (i.e., ovarian cyst/mass(s) and/or uterine leiomyoma(s)), previous abdominal and/or pelvic surgery, received exogenous hormones within the last year, and/or refused to participate.

The studied adolescents were divided into underweight, normal-weight, overweight, and obese groups based on their BMI (kg/m2) [11, 12].

Regular cyclic menstrual flow is defined as menstrual flow on a regular basis every 21–35 days.

Underweight adolescents mean adolescents with BMI < 18.5 kg/m2. Normal weight adolescents mean adolescents with BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2. Overweight adolescents mean adolescents with BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2. Obese adolescents mean adolescents with BMI > 30 kg/m2 [11, 12].

The severity of the studied adolescents’ dysmenorrhea was assessed by the VAS [13]. The visual analogue scale score of 0 equals no menstrual pain and/or dysmenorrhea. The visual analogue scale score of 10 equals severe menstrual pain and/or dysmenorrhea. Collected data were analyzed using the ANOVA test and correlation analysis (Pearson’s correlation) to assess the relation between primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and BMI.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated by G Power 3.1.9.7 with 0.05 probability, 0.95% power, and 0.25 sample size. Collected data were analyzed using the ANOVA test, and correlation analysis (Pearson’s correlation).

Results

The four studied adolescent groups were matched with no difference regarding the mean age (years) (14.2 ±1.7 for the underweight adolescent group, 14.6 ±1.8 for the normal-weight adolescent group, 15.1 ±1.7 for the overweight adolescent group, and 14.9 ±1.6 for the obese adolescent group).

The 4 studied adolescent groups were matched with no difference regarding the mean height (cm) (158.7 ±2.5 for the underweight adolescent group, 158.8 ±2.8 for the normal-weight adolescent group, 160.0 ±2.4 for the overweight adolescent group, and 158.8 ±2.3 for the obese adolescent group).

The classification of the studied adolescents according to their BMI explains the significant difference between the 4 studied adolescent groups regarding their weight (kg), and BMI (kg/m2): 44.6 ±2.05 and 17.7 ±0.5, respectively for the underweight adolescent group, 58.3 ±4.5 and 23.1 ±1.4, respectively for the normal-weight adolescent group, 67.5 ±3.1 and 26.4 ±0.9, respectively for the overweight adolescent group, and 77.9 ±2.6 and 30.9 ±0.5, respectively for the obese adolescent group (Table 1).

Table 1

The ANOVA test analysis of the studied groups characteristics

BMI – body mass index, DF – degrees of freedom between groups, F – statistical test of ANOVA analysis (ANOVA coefficient), MS – mean of squares between groups, N – number, SD – standard deviation, SS – sum of squares between groups, VAS – visual analogue scale

Normal group: BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, obese group: BMI > 30 kg/m2. One way ANOVA test used for analysis of variance between the studied groups. Overweight group: BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2. Significant value < 0.05 according to post-hoc Tukey HSD (HSD.05 = 0.9076 and HSD.01 = 1.1044). Underweight group: BMI <18.5 kg/m2. Data presented as mean ±SD

The visual analogue scale of dysmenorrhea was statistically higher in the underweight adolescent group (8.7 ±0.8) compared with the VAS of the normal-weight (6.5 ±0.5) (p = 0.000001), and overweight (6.3 ±0.6), (p = 0.000001) adolescent groups.

The visual analogue scale of dysmenorrhea was also statistically higher in the obese adolescent group (9.4 ±0.6) compared with the VAS of the underweight (8.7 ±0.8) (p = 0.000001), normal-weight (6.5 ±0.5) (p = 0.000001), and overweight (6.3 ±0.6) (p = 0.000001) adolescent groups (Table 1).

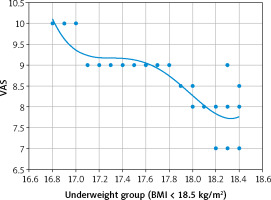

Although there was no detected relation between the VAS and BMI in the normal-weight (r = –0.041; p = 0.760), and overweight (r = 0.063; p = 0.59) adolescent groups in this research, there was a strong negative relation between the VAS and BMI in the underweight adolescent group (r = –0.862; p < 0.00001) (Fig. 1). In addition, there was a moderate positive relation between the VAS and BMI in the obese adolescent group (r = 0.706; p < 0.00001) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Dysmenorrhea negatively affects the QoL and work productivity [6]. The previous results regarding primary dysmenorrhea and its relation to BMI are inconsistent and controversial [7].

The younger generation’s QoL and the early treatment of diseases are crucial goals in the Republic of Kazakhstan [10]. Therefore, this research was designed to assess the relation between primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and BMI.

A meta-analysis found that underweight participants were at greater risk of primary dysmenorrhea [7], and cross-sectional research reported higher prevalence of moderate and severe dysmenorrhea in underweight girls compared to normal controls [5].

Comparative research found that women with > 27.5 kg/m2 BMI had significantly increased risk of dysmenorrhea compared to normal controls [8], and a positive relation between dysmenorrhea and BMI was also observed in another two studies [14, 15].

This study found that VAS of dysmenorrhea was statistically higher in the underweight adolescent group (8.7 ±0.8) compared with the VAS of the normal-weight (6.5 ±0.5) and overweight (6.3 ±0.6) adolescent groups, and there was a strong negative relation between the VAS and BMI in the underweight adolescent group (p < 0.00001).

The visual analogue scale of dysmenorrhea was also statistically higher in the obese adolescent group (9.4 ±0.6) compared with the VAS of the underweight (8.7 ±0.8) (p = 0.000001), normal-weight (6.5 ±0.5) (p = 0.000001), and overweight (6.3 ±0.6) (p = 0.000001) adolescent groups, and there was a moderate positive relation between the VAS and BMI in the obese adolescent group (p < 0.00001).

Similarly, EL-kosery et al., in a correlational study, found that both the obese and underweight participants were at increased risk of primary dysmenorrhea compared to normal-weight and overweight controls [1].

An increased odds of dysmenorrhea was reported in underweight and obese participants [9], and an increased risk of dysmenorrhea was also reported in participants with lower or higher BMI [16]. Moreover, a significant relation between BMI and dysmenorrhea was reported by Kaur et al. [17].

This research was the first cross-sectional research carried out in the Republic of Kazakhstan to assess the relation between primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and BMI.

The visual analogue scale of dysmenorrhea was statistically higher in the underweight adolescent group compared to normal-weight and overweight adolescent groups in this study. In addition, the VAS of dysmenorrhea was statistically higher when the obese adolescent group was compared with the overweight, normal-weight and underweight adolescent groups.

Dysmenorrhea negatively affects the QoL and work productivity [6]. The effect of dysmenorrhea on the QoL needs further research.

Conclusions

The visual analogue scale of dysmenorrhea was statistically higher in the underweight adolescent group compared to normal-weight and overweight adolescent groups, and there was a strong negative relation between the VAS and BMI in the underweight adolescent group. In addition, the VAS of dysmenorrhea was statistically higher when the obese adolescent group was compared with the overweight, normal-weight and underweight adolescent groups, and there was a moderate positive relation between the VAS and BMI in the obese adolescent group.