Introduction

Pharmacies are subject to strict standards of safety and quality of services in many countries of the world, including Ukraine [1-3]. The pharmacy environment may well be a significant reservoir of potential pathogens. Visitors to pharmacies can often be in the incubation period of an infectious disease, or be a carrier of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms in the upper respiratory tract which are transmitted by airborne droplets, unwashed hands or direct contact with an inanimate object or equipment. This can potentially increase the presence of these pathogens [4,5]. Visitors, especially those with compromised immune systems or other medical conditions, may be at risk in indoor airspace because enclosed spaces contain aerosols and allow them to multiply to infectious levels [6-8]. Therefore, it is extremely important to evaluate/carry out microbial control in on-site pharmacies. Airborne microorganisms and other sources of contamination in pharmacies must be minimized because there are many people who pass through pharmacy premises.

Aim of the work

The purpose of the study was to determine the composition of microbial contamination of pharmacy room displays using the dominance index.

Material and methods

The samples were collected from 26 pharmacy establishments, including pharmacy showcases and barriers located between customers and pharmacists during communication. The samples were collected using sterile cotton swabs contained in disposable plastic tubes filled with 0.9% sodium chloride solution (NaCl) (YURIAPHARM, Ukraine) (to maintain the balance between cells and the surrounding environment). These samples were transported to the laboratory within 2 hours at room temperature +18-+22 °C. Subsequently, cultures were performed on selective and differential nutrient media and incubated at the optimal temperature 37 °C for 24-48 hours. To cultivate cocci bacteria, mannitol-salt agar (Biolife Italiana S.r.I.) and blood agar (Biolife Italiana S.r.I.) were used. For the detection of Enterobacteriaceae Endo medium (Biolife Italiana S.r.I.) was used, and Sabouraud medium (FARMAKTIV LLC, Ukraine) was applied for fungal isolation. Microorganisms were Gram-stained and identified using standard biochemical tests, following the «Methods for the Identification of Bacteria» scheme [9] and with the Manual of clinical microbiology procedures, volumes 1-3, 4th edition, serving as a reference [10]. Quantitative counting was performed by determining colony-forming units (CFU). Data were collected and tabulated using MS Excel 2013, and qualitative data were presented as percentages and proportions. The dominance index was determined based on the number of occurrences of a particular microorganism species in the population of the tested samples. It was calculated using the formula: C% = n × 100 / N, where C% is the dominance index, n is the number of samples in which the investigated species was detected, and N is the total number of analyzed samples [10]. To interpret the results the following scale was applied: species with a constancy index exceeding 50% were considered dominant, those occurring frequently ranged from 20 to 50%, those encountered infrequently were between 1 and 19%, and those rarely encountered were less than 1%.

Results

In the study of 26 washes, 74 strains of microorganisms were found. A total of 12 genera of microorganisms, Micrococcus, Staphylococcus, and Bacillus were recorded, accounting for 29.73%, 28.38%, and 18.92% of the total number of genera of microorganisms detected in the samples obtained from pharmacy showcases. The relative number of genera Streptococcus, Neisseria, Escherichia, Moraxella and fungi Candida ranged from 2.70% to 5.40% of the total number of detected microorganisms. Bacteria of the genera Acinetobacter, Yersinia, Klebsiella, and Mobiluncus in the studied samples accounted for 1.35% of the total number of bacteria.

The bacteriological analysis of the samples obtained from pharmacy showcases revealed the presence of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms. Among the Gram-positive ones, which constitute 36.50% of the entire microbiota, representatives of the following genera were identified: Micrococcus, Bacillus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus. Gram-negative microorganisms accounted for 54.40% of the obtained biodiversity, including Acinetobacter spp., Neisseria spp., Escherichia spp., Yersinia spp., Klebsiella spp., and Moraxella spp. Additionally, one sample yielded a representative of Gram-variable microorganisms – Mobiluncus spp., which corresponds to 9.10% of all identified genera of bacteria (a total of 11 genera of bacteria were identified) (Table 1).

Table 1

The isolates of microbiological contamination in the pharmacy room displays

The results of a quantitative microbiological study of the surface of pharmacy showcases revealed bacteria of the genus Micrococcus in number (107-108 CFU/ml). Among bacteria of the genus Staphylococcus, the number of which in the washings was from 106 to 107 CFU/ml, the most pathogenic species is Staphylococcus aureus, which was found in three samples, which is 11.41%. However, its concentration in the tested samples is less than 105 CFU/ml, which does not pose a risk to pharmacy visitors. Other representatives of the Gram-positive microbiota, Bacillus spp. and Streptococcus spp., were found 104-105 CFU/ml, 103-104 CFU/ml, respectively, in the studied washings. Representatives of Gram-negative and variable microbiota from 101 to 103 CFU/ml and fungi of the genus Candida ≤ 102 CFU/ml were also found on the surface of the showcases.

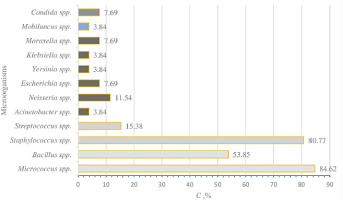

Based on the calculation of the dominance index, Micrococcus spp. , Bacillus spp., and Staphylococcus spp. are considered constant, with a constancy index exceeding 50.01% (Figure 1). The rest of the Gram-positive bacteria and Candida spp. microflora fungi should be categorized as infrequent (1.01-19.01%).

Among the Gram-negative microorganisms, the leading positions are held by representatives of the following genera: Neisseria, Moraxella, Escherichia. Additionally , Acinetobacter, Yersinia, and Klebsiella were found sporadically. The diagram indicates that their occurrence rates are one order of magnitude lower than those of the Gram-positive representatives. Upon further analysis of the obtained samples, all Gram-negative microorganisms are classified as those encountered infrequently (1.01-19.01%) based on the dominance index.

The highest dominance index is found in microorganisms typically present in the human respiratory tract: Neisseria spp. – 11.54% and Moraxella spp. – 7.69%. Escherichia spp., which are part of the human gastrointestinal tract, also show a dominance index of 7.69%. Similarly, with the same frequency, representatives of the Escherichia genus were found in the samples (7.69%). Additionally, isolated instances involved the identification of Acinetobacter spp., Yersinia spp., and Klebsiella spp.

Discussion

The results of the analysis of samples from showcases regarding the presence of Gram-positive microorganisms are consistent with published data [11]. Air serves as one of the environments that promotes the spread of various types of microorganisms, and surrounding objects act as potential objects of contamination. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that pharmacy visitors can be contaminated with various microorganisms both by direct airborne droplets and indirect airborne dust, when microorganisms settle on the surface of various objects, namely, storefronts in pharmacies [11]. Air is not a typical environment for microorganisms, and it is mainly used as a medium for transmission. Most microorganisms are associated with physical particles in the air and mainly consist of endospore-forming microorganisms, such as Bacillus spp. [12].

One of the important factors in increasing or decreasing the number of microorganisms in the air or on various surfaces is the influence of environmental factors. Many studies have confirmed the impact of such factors as temperature, humidity, and solar radiation on the composition of the bacterial community. In particular, the influence of air temperature on the pathogens Escherichia spp. and Bacillus spp. has been studied, and it has been demonstrated that the number of Gram-negative bacteria is reduced compared to Gram-positive ones [13], which is confirmed in our study, in which the proportion of Bacillus spp. was 18.92%, and Escherichia spp. was only 2.70% in the samples examined.

In addition, the dominant microorganisms in our research are bacteria from the genera Micrococcus (29.73%) and Staphylococcus (28.38%), which is supported by studies conducted both in Poland and Beijing [14,15]. When infecting a person with certain health complications the identified microorganisms can lead to various pathological conditions. In particular, representatives of the genus Micrococcus can cause purulent-inflammatory diseases of the skin and upper respiratory tract. In people with a normally functioning immune system, Micrococcus luteus, for example, is not usually considered harmful. And bacteria of the genus Staphylococcus, which includes species that are considered opportunistic, including Staphylococcus aureus, belong to the group of sanitary-indicative air microorganisms and are a frequent cause of skin infections, food poisoning, and hospital-acquired infections. Other species of Staphylococcus can sometimes cause infections in individuals with weakened immune systems or chronic respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [16].

While representatives of the genus Streptococcus (5.40%) are also commonly found in various environments and may be part of the human body’s microbiota, they were much less frequently isolated during the study. This can be explained by their lower resistance to the environment [13,17].

Representatives of the genus Neisseria (4.06%) were found in our study and are usually part of the normal microbiota in the nasopharynx and upper respiratory tract, and potentially can be released into the air and subsequently settle on various surfaces in the pharmacy, which is confirmed by the presence of these microorganisms in the air in the studies of Hewitt et al. [18].

The percentage of Yersinia spp. , Klebsiella spp. , Mobiluncus spp., and Candida fungi in the examined samples was 1.35-2.70%. The presence of bacteria from the Enterobacteriaceae family on the surface of the pharmacy room displays is of concern, as these microorganisms are indicative of sanitary conditions in the case of fecal contamination [19]. The study results showed the presence of conditionally pathogenic microbiota on the surface of pharmacy room displays. Therefore, it is important to analyze and control the contamination of pharmacy premises as potential places of people gathering in the room, which may lead to the spread of pathogenic microorganisms transmitted by airborne droplets and alimentary transmission.

Conclusions

The conducted study of the samples demonstrated the presence of 12 genera of microorganisms that contaminated the surfaces of pharmacy room displays. The detected microorganisms belong to the permanent or transient microbiota of human skin, respiratory tract and air. In particular, Bacillus spp. Micrococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. were dominant representatives in samples of the studied material. Isolates from the genera Mobiluncus, Acinetobacter, Yersinia and Klebsiella were found as single occurrences. The results of bacteriological analysis show that it is important to emphasize that the isolated species of microorganisms are characteristic of such types of investigated objects.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Specifically, the sample size was relatively small and may not be representative of the overall population. Additionally, the study only used a cultural method to analyze the contamination of pharmacy window surfaces, which may not capture all bacterial taxa present on indoor surfaces. To confirm these findings and identify other microbial associations, future research with larger sample sizes and the use of more advanced research methods is needed.