Severe blunt cardiac injury (BCI) usually leads to the development of haemorrhagic or cardiogenic shock. In case of ineffective initial resuscitation and excluded significant blood loss, cardiogenic factors should be considered. BCIs requiring operative treatment include cardiac rupture, pericardial herniation, heart dislocation or rotation, and significant intracardiac injury. In all cases the diagnosis of pericardial rupture and heart luxation is made intraoperatively.

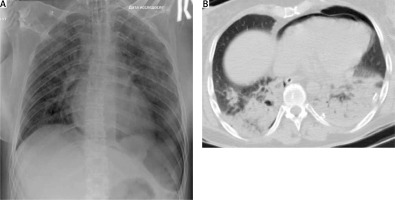

A 39-year-old woman fell from a height of approximately 18 m. On admission, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 3/4. An oropharyngeal tube was in place, with fresh blood emerging from it (the respiratory rate was 6 to 8/minute). There was crepitating wheezing over whole lung surfaces and decreased lung sounds on the left. Tachycardia was observed (heart rate was 120 to 140 bpm), with systolic blood pressure 70 mm Hg and oxygen saturation (Sat O2) of 82% with 15 l/min of oxygen supplementation. The patient was immediately intubated, which led to an increase of Sat O2 to 90% and BP to 90/70 mm Hg. Extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (eFAST) was performed and left pleural effusion was revealed. Due to ongoing hypotension and the absence of a hemodynamic response to fluid therapy, an infusion of 0.8 μg/kg/min norepinephrine was started. Left scapula and 3–9 left rib fractures, left-sided pneumohydrothorax as well as left ischial bone fracture were found on X-rays of the chest and pelvis, respectively. A left thoracostomy tube was inserted and 500 ml of blood was evacuated. After that the patient was transferred for a computed tomography (CT) scan, which revealed pneumopericardium and bilateral lung contusions. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Echocardiography revealed no damage of intracardial structures, but there was an increase in the echo signal on the myocardium and pericardium below the mitral valve, which was regarded as their contusion in this zone. The dynamics of changes in chest X-ray, pneumopericardium on CT along with negative echocardiography findings could neither prove nor exclude pericardial rupture and heart luxation (Figure 1). Bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy performed on the second day excluded any ruptures of relevant structures as a possible cause of pneumopericardium. On the fourth day left-sided video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) was performed. By the beginning of the surgery, the patient continued to be on mechanical ventilation, which was associated with significant bilateral lung contusion. Her hemodynamics were stable, without sympathomimetic support. In the operating room, after placing the patient in the required position, the endotracheal tube under the control of the bronchoscope was positioned in the right bronchus. Anaesthesia: sevoflurane + fentanyl. With one-lung ventilation, there was a decrease in Sat O2 to 82–84%, which was corrected by an increase in FiO2 from 0.65 to 0.95. During the operation, according to the ECG, rhythm disturbances periodically occurred in the form of polytopic extrasystoles, sometimes in complexes of 3–5 extrasystoles, which was associated with touches of endoscopic instruments to the myocardium and required IV administration of metoprolol 5 mg. Intraoperatively there occurred a large 12 cm longitudinal tear of the pericardium along the anterior border of the phrenic nerve from the pulmonary artery to the diaphragm; the larger part of the heart was beating free in the left pleural cavity, without any signs of luxation or ischaemic ECG changes. These observations, lung contusion and swelling of the heart led to the decision not to suture the pericardial rupture found (Figure 2). A chest drain was placed in the left pleural cavity. After placement of pleural drainage, the endotracheal tube was transferred to the trachea, and FiO2 was reduced to 0.6. Heart rhythm disturbances did not recur. One day after surgery, the patient was routinely extubated. On the third postoperative day the chest drain was removed. VATS confirmation of diagnosis of pericardial rupture can be a part of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programm in emergency thoracic surgery. The follow-up period is 4 years. The patient has returned to normal daily activity without any consequences.

Figure 2

Intraoperative findings of pericardial rupture (A), postoperative chest X-ray (B), and postoperative wound (C)

During the first half of the last century, pericardial rupture with or without heart luxation was a postmortem diagnosis found on autopsy [1]. The motor vehicle crash of Princess Diana in 1997 was an example of death due to pericardial rupture and heart luxation. Pneumopericardium may lead to tension and cardiac tamponade. However, concurrent conditions, such as cardiac contusion, shock lung, intravascular volume depletion, and tension pneumothorax may confuse the clinical picture [2]. The identification of pneumopericardium by chest radiography was described by Wenkenbach in 1920 and elaborated upon by Cimmino in 1967. In most studies CT is the most accurate method of diagnosis of pneumopericardium, but in 80% of cases the diagnosis was achieved in the course of surgery performed for associated lesions. Until 2022 there were a few reports of VATS diagnosis of pericardial rupture published in the literature [3]. Timing of prompt diagnosis influences treatment modality of this usually life-threatening condition and is essential for a better outcome.