The global incidence of chronic kidney disease is on the rise, leading to an escalating demand for renal replacement therapy. Establishing a permanent access for dialysis is crucial in managing these patients [1]. For individuals awaiting permanent vascular access, temporary access through a catheter in the internal jugular vein may be necessary. However, this neck cannulation poses the risk of complications, such as stenosis or complete occlusion of the central vessels [2].

Central venous stenosis (CVS), a long-term complication affecting 16–27% of hemodialysis patients, often arises from catheter-based access procedures [1]. In cases of central venous stenosis, an ipsilateral fistula operates against elevated blood flows and venous pressures, leading to upper extremity swelling. This swelling can result in challenges with fistula cannulation, venous congestion, ulceration, and, in severe cases, venous gangrene.

Recently, an endovascular approach utilizing balloon venoplasty has gained traction, initially aimed at symptom relief and maintaining fistula patency. In instances where the endovascular approach proves unsuccessful, surgical interventions, such as direct open venoplasty repair or extraanatomical bypass procedures, become viable alternatives. It is worth noting that open surgical venoplasty is associated with higher mortality and morbidity rates within this patient population.

In this report, we delineate the methodology employed to salvage the fistula in a patient suffering from central venous occlusion, accompanied by a concise overview of the literature on this condition.

The patient presented to the outpatient clinic with complaints of swelling in the left arm, head, and neck. The 59-year-old male patient was receiving 3/7-day hemodialysis from a fistula that opened 5 years ago in the left arm. In addition to chronic kidney failure, the patient also has diabetes and coronary artery disease. Before hospitalization the patient had been suffering from increasing swelling in the left arm, in the head and in the neck region for the last 6 months. The patient underwent difficult cannulation and then he received dialysis against high pressure during hemodialysis.

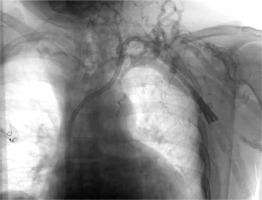

The patient’s upper extremity Doppler and left upper extremity venography, conducted at an external center, revealed total occlusion (Figure 1). Due to the impassable lesion resulting from complete blockage, only diagnostic imaging could be performed. Subsequently, hospitalization was deemed necessary for further investigation and treatment. Venous phase upper extremity computed tomography angiography revealed the condition. The right subclavian vein was identified as patent, prompting the decision to plan a subclavian venous cross-over bypass from left to right. Following preoperative preparations for the patient, the surgical procedure was initiated.

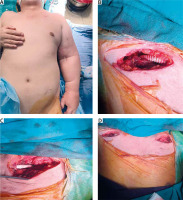

Under general anesthesia, incisions were made under both clavicles to locate the subclavian veins. An 8 mm ringed PTFE graft was passed under the skin through tunnels in the chest region, and end-to-side cross-over venous bypass from left to right was performed. At the end of the procedure, a thrill was obtained from the distal end of the graft. Perioperative photographs are presented in Figures 2 A–D.

Figure 2

Perioperative images: A – diffuse swelling in left arm, B – right subclavian zone, C – left subclavian zone, D – intraoperative surgical area

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit after the surgery. The following day, the patient was placed under service monitoring. Anticoagulation was initiated with DMAH (1 × 0.4 ml enoxaparin) and 2 days later switched to warfarin. In addition to anticoagulant therapy, the patient was advised to elevate the arm and apply a mildly compressive elastic bandage. Before discharge, the swelling in the left arm and head-neck region had noticeably decreased (Figure 3 A).

Figure 3

Postoperative images: A – 1st day; the tension in the skin has decreased, B – 3rd month; it can be seen that the swelling has almost completely disappeared

During the follow-up visit at 3 months, a significant clinical improvement in the left arm was evident, and the patient continued dialysis through the fistula (Figure 3 B). Doppler ultrasonography conducted at this visit revealed the ongoing patency of the graft. However, likely due to the effective international normalized level (INR) level (between 2.5 and 3.5), thrombosis did not occur, allowing the patient’s extraanatomic bypass graft to continue functioning.

Ensuring the continuity of access in a patient with an arteriovenous (AV) fistula is crucial, especially for those who have been on dialysis for a long time.

Central venous occlusions occur with a frequency of up to 20% depending on the patient profile and the diagnostic method used [3]. Although they often remain asymptomatic, when there is a functioning AV fistula or AV graft on the same side extremity, common symptoms include widespread edema in the arm, prominent collaterals on the chest wall, bleeding from puncture sites, reduced dialysis efficiency, and facial edema. The underlying causes are usually related to previous catheter placements, less commonly high-flow AV fistulas, and external pressures such as venous thoracic outlet syndrome. For diagnosis, fistulography or, especially when considering external compression, computed tomography (CT) angiography should be performed [4].

The occlusion of the central vein over time and the failure of the applied endovascular treatment bring the use of surgical venous bypass solutions into consideration in such cases. These types of surgery can be performed as ipsilateral and contralateral venous bypass to the internal jugular vein (IJV), or as ipsilateral femoral vein bypass [5].

The management of lesions in central veins is usually initiated with endovascular intervention requiring angioplasty for stenotic lesions. As noted by Krishna et al. in their series, recurrence is common in diseases of central veins due to the elastic nature of the vein, necessitating repeated percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) procedures. Consequently, the 1-year primary patency rate after PTA of central venous lesions is only 20%. The placement of stents does not improve these results [6]. Despite being invasive, surgical bypasses are more durable than venoplasty. In a 12-month follow-up, patients who underwent surgical bypass had a patency rate of 75% compared to 63% in those treated with angioplasty [7].

Based on the publications in the literature suggesting that surgical bypass is more effective in the long term, we also performed a surgical veno-venous bypass in this case. Early anticoagulation was initiated post-surgically to maintain graft patency. Anticoagulation was achieved using low-molecular-weight heparin in the early postoperative days and later with the addition of warfarin. Additionally, we observed that arm elevation and the application of low-pressure elastic bandages reduced swelling in the arm.

In our case, no infectious complications were observed. With effective INR levels and the use of elastic bandages, the swelling in the left arm had completely disappeared at the third-month follow-up, and graft patency was maintained.

In conclusion, the approach to central venous occlusions should primarily focus on solutions that preserve the functioning fistula. Endovascular or surgical procedures should be considered together to achieve fistula patency and alleviate the patient’s symptoms.