Introduction

Following cisplatin and carboplatin, oxaliplatin (OXA) has emerged as the third generation platinum-based chemotherapeutic drug that has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [1]. It causes cell death by binding to DNA and forming cross-links. This in turn prevents DNA replication and transcription [1, 2]. This mechanism is similar for all platinum-based cytotoxic drugs that influence the production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon DNA and mitochondrial damage in malignant cells. In addition, OXA interacts with reduced glutathione (GSH), and depletion of GSH is one of the necessary pathways for the cytotoxic effect obtained through ROS production [2–4].

Since the FDA’s approval in 2002, OXA has been commonly used not only in the treatment of stage III and IV colorectal cancer but also in systemic treatment of some other cancer types such as ovarian, breast, stomach, pancreas, testicular cancers and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [1, 5]. As its clinical use became widespread, the information related to the frequency and management of OXA-induced adverse effects also increased. Although it appears structurally similar to cisplatin, OXA consists of a 1,2-diaminocyclohexane bearer ligand which results in a different adverse effects profile than cisplatin [4]. The nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity frequencies are lower than those of cisplatin, and the myelosuppression frequency is lower than that of carboplatin [6]. Although it varies significantly, OXA-induced neurotoxicity is an important side effect seen in most patients. The neurotoxicity experienced as a result of this drug involves both acute and chronic sensorial and motor neuropathies [6, 7]. Hematological and gastrointestinal toxicity should be kept in mind as other frequent side effects [7]. However, previous studies have not defined the profile and the prevalence of OXA-induced pulmonary toxicity yet.

Treatment-related pulmonary damage occurs in approximately 5–10% of cancer patients who receive chemotherapy [8]. It most frequently presents as pneumonitis/fibrosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. While bleomycin, mitomycin, cyclophosphamide, and busulfan comprise the most common reasons for pneumonitis/fibrosis, paclitaxel, docetaxel and methotrexate are typically responsible for hypersensitivity pneumonitis [8, 9]. Currently available data in the literature related to OXA-induced pulmonary toxicity are based mostly on case reports and pulmonary toxicity patterns, so the underlying mechanism and associated factors have not been described comprehensively [8, 9]. Animal studies on OXA-induced pulmonary toxicity are also very limited [10–13].

In this study, we aimed to demonstrate the short- and long-term effects of OXA treatment on lung tissue. Additionally, if there were any significant findings in biochemical and histopathological parameters, the reversibility of the relevant findings was also studied within the follow-up periods after the last administration of the drug.

Material and methods

Animals and experimental design

A total of 40 female 6–8 month old Wistar rats were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of our university and all experiments were performed according to the principles and guidelines of the University Ethical Committee (UEC). The rats were kept in an environmentally controlled room at constant temperature (21 ±1°C) and humidity (75 ±5%) under a 12 h light/dark cycle. The animals were acclimatized for 1 week prior to the study and had free access to standard laboratory feed and water ad libitum. The study was originally planned to investigate OXA-auto-toxicity; however, in order to reduce the number of animals used in medical research, a new ethics committee approval was obtained to evaluate the pulmonary toxicity of the lung tissues of the animals (HADYEK/2014/162).

The animals were randomly divided into five study groups (Table 1). Each group consisted of 8 animals. Prior to intra-peritoneal (i.p.) administration, the OXA (Eloxatin, Sanofi, U.S.) dose of 4 mg/kg was diluted in a 5% glucose solution:

Table 1

Total oxaliplatin doses and application schema and re-classification of the groups according to oxaliplatin administration

group 1: sham group, glucose 5%, 1 ml was administered i.p. on days 1, 3, and 5 and the rats were sacrificed on day 14,

group 2: OXA was injected on days 1, 3, and 5 and the rats were sacrificed on day 7,

group 3: OXA was injected on days 1, 3, and 5 and the rats were sacrificed on day 14,

group 4: OXA was injected twice a week (Monday and Thursday) for 4 weeks and the rats were sacrificed on day 28,

group 5: OXA was injected twice a week (Monday and Thursday) for 4 weeks; after the completion of the injections, the rats were sacrificed on day 48 [8].

The OXA dosage was adjusted according to the study by Caveletti et al. [14] and no animals were lost during the study procedures. The research aimed to determine both acute and chronic toxic effects through the dosages, which did not exceed the lethal dosage (15 mg/kg per week). The groups were further classified into three groups according to the treatment courses: sham group (group 1), short-term group (groups 2 and 3), and long-term group (groups 4 and 5) (Table 1). Groups 2 and 3 were monitored for a short period (7–14 days) following OXA injection; groups 4 and 5 were monitored for a longer period (28–48 days) after OXA injections to examine the reversibility of possible acute damage.

We sacrificed the rats under anesthesia at specified times determined for each group (Table 1). Anesthesia was induced by a single i.p. injection of ketamine (Ketalar, Pfizer, 50 mg/kg) and xylazine (Alfazyne 2%, 5 mg/kg) The blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and the lungs were harvested and kept at –80°C for histopathological evaluation.

Preparation of tissue specimens

After being weighed, the lung tissues were processed and kept on ice at all times with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) at appropriate rates and homogenized with a homogenizer (Randox Reagents Rx Series, Northern Ireland) for 10 minutes at 8000 rpm. After homogenization, sonication (Abbott C8000, United States) was performed to strengthen the effect of the homogenization procedure. The homogenate was centrifuged in a cooled centrifuge at +4ºC for 10 minutes at 6000 rpm, and the supernatant fraction was removed.

Determination of glutathione peroxidase levels

The glutathione peroxidase (GPX) method was based on the procedure as described by Paglia and Valentine [15]. GPX catalyzes the oxidation of GSH by cumene hydroperoxidase. In the presence of glutathione reductase and NADPH, the oxidized GSH (GSSG) is immediately converted to its reduced form (GSH) with a concomitant oxidation of NADPH to NADP as shown below:

2 GSH + ROOH + GSH-Px → ROH + GSSG + H2O

GSSG + NADPH+ + H+ GR → NADP+ + 2 GSH

Measurement of decrease in absorbance was performed at 340 nm (Ransel Glutathione Peroxidase, Randox, United Kingdom). GPX level was measured in tissue protein homogenate using an Abbott protein kit auto-analyzer (Architect, Abbott, United States), and expressed as mg/dl. GPX activity was expressed as U/l. Lung tissue GPX activity results were given as U/mg tissue protein.

Histopathological examination of lungs

The lung samples of the rats in each group were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours. Rinsing was done with tap water, and then serial dilutions of alcohol (methyl, ethyl and absolute ethyl) were used for dehydration. The specimens were cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin at 56°C in a hot-air oven for 24 hours. Paraffin beeswax tissue blocks were prepared for sectioning at 5 μm thicknesses by a microtome (Leica Tissue Microtome Model RM 2125T; Leica Microsystems-Nussloch GmbH, Germany). Lung tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined by light microscopy (Olympus Clinical Microscope Model BX46, Olympus Cooperation, U.K.). Along with that, Masson-Trichrome stain was used for histopathological examination.

Pulmonary damage due to OXA was assessed based on six parameters: 1) interstitial pneumonia (the lymphocytic infiltration in the parenchyma of the lung), 2) interstitial fibrosis (increased collagen in the parenchyma of the lung around the alveoli), 3) parenchymal hemorrhage for acute or chronic damage, 4) intra-alveolar/interstitial macrophage presence (presence of macrophages both in and between the alveoli), 5) eosinophil existence (presence of eosinophils both in and between the alveoli), and 6) granuloma existence (presence of granulomas in the parenchyma of the lung around the alveoli).

All parameters were separated into 4 sections in terms of their severity and scored semi-quantitatively. The scoring system was as follows: 0: absent (no interstitial lymphocytic inflammation, no fibrosis, no type 2 pneumocyte infiltration, no macrophages, no eosinophils, and no granulomas), 1: mild (a few lymphocytes, type 2 pneumocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, granulomas, and minimal fibrosis), 2: moderate (between score 1 and score 3), and 3: severe (diffuse infiltration of excessive number of lymphocytes, type 2 pneumocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, granulomas and excessive diffuse fibrosis) [16]. We also further analyzed the percentages of histopathological findings regardless of the severity grading (as 1: present vs. 0: absent) between three groups (sham group, short-term and long-term OXA administered groups) with the χ2 test.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 22.0 (IBM Statistics for Windows version 22, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, United States) software was used in the analysis of data. The conformity of the data to normal distribution was analyzed based on the Shapiro-Wilk test. The one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA, Robust test: Brown-Forsythe) was used in comparison of multiple independent groups. For comparison of categorical data, Pearson’s χ2 test was used based on the Monte Carlo simulation technique. The categorical data were classified in numbers (n) and percentages (%). The Jonckheere-Terpstra test was used in comparisons between reduced-dose/short-term (groups 2 and 3), higher-dose/long-term administered groups (groups 4 and 5) and the sham group. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the tissue GPX levels between groups as a post-hoc test if the p value was significant in the Kruskal-Wallis test. The data were analyzed at a 95% confidence level, two-tailed and a p value of less than 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

All of the animals that received OXA were able to complete the study and no death was observed. There was no significant difference between study groups in terms of weight change throughout the study (p > 0.05).

Histopathological results

Total OXA doses and application scheme and classification of the study groups according to OXA administration are given in Table 1.

When the sham group was compared with the lower-dose/short-term and higher-dose/long-term OXA administration groups, no significant difference was found between the groups in terms of interstitial fibrosis (p > 0.05), parenchymal hemorrhage (p > 0.05), or granuloma presence (p > 0.05). However, the rats that received higher-dose/long-term OXA had significantly increased intra-alveolar/interstitial macrophage (p < 0.05) and eosinophil (p < 0.05) presence and a higher rate of interstitial pneumonia (p < 0.05) compared to the sham group and low-dose/short-term group (Table 2). In addition, we compared all groups (sham vs. low-dose/short-term vs. high-dose/long-term groups) in terms of the frequencies of histopathological findings regardless of the severity grading (as 1: present or 0: absent) with χ2 test and found similar results with the former comparison. No significant difference was found between three groups regarding the frequencies of interstitial fibrosis, parenchymal hemorrhage, or presence of granuloma whereas the frequency of interstitial pneumonia and the presence of intra-alveolar/interstitial macrophage and eosinophil were increased in the high-dose/long-term group compared with the sham group to (Table 3).

Table 2

Comparison of histopathological features of study groups re-classified based on OXA doses and application schema

| Features | Group 1 (sham group) n = 7 | Groups 2 and 3 (low-dose/short-term) n = 16 | Groups 4 and 5 (high-dose/long-term) n = 16 | pα |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interstitial pneumonia | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0.029b |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.103 |

| Parenchymal hemorrhage | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.593 |

| Intra-alveolar/interstitial macrophages | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–2) | 0.008bc |

| Presence of eosinophils | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0.020bc |

| Presence of granuloma | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0.109 |

Table 3

Comparison of percentages of histopathological findings between groups after re-classification based on oxaliplatin doses and application schema

| Features | Group 1 (Sham group) n = 7 | Groups 2 and 3 (low-dose/short-term) n = 16 | Groups 4 and 5 (high-dose/long-term) n = 16 | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interstitial pneumonia, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (19) | 6 (38) | 0.044 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 5 (31) | 0.057 |

| Parenchymal hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.753 |

| Intraalveolar/interstitial macrophages | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (31) | 0.013 |

| Presence of eosinophils | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (25) | 0.029 |

| Presence of granuloma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 0.132 |

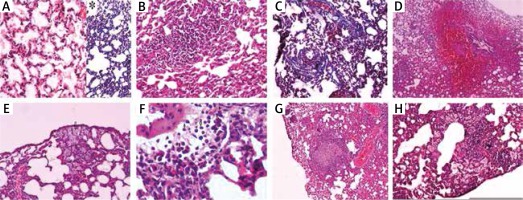

The histopathological features used to describe pulmonary OXA toxicity under the light microscopy were depicted in Figure 1.

Fig. 1

A) Normal lung tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E ×100), and *Masson trichrome (MTC) stain showing no inflammation, hemorrhage or fibrosis. B) Lymphocytic infiltration is seen in pulmonary parenchyma named as interstitial pneumonitis (H&E ×100). C) Interstitial fibrosis areas due to increased collagen synthesis in pulmonary parenchyma around the alveoli can be seen as blue with Masson trichrome stain (MTC ×100). D) Substantial amount of erythrocytes in the alveolar and interstitial spaces indicating pulmonary parenchymal hemorrhage (H&E ×40). E) A number of macrophages can be seen both in the intra-alveolar and interstitial spaces (arrows) (H&E ×100). F) A number of eosinophils can be seen both in the intra-alveolar and interstitial spaces (arrows) (H&E ×400). G) Depicts a granuloma formation in the pulmonary parenchyma (H&E ×40). H) A number of macrophages can be seen in both intra-alveolar and interstitial spaces together with lymphocytic infiltration in pulmonary parenchyma indicating interstitial inflammation/pneumonitis (H&E ×100)

Biochemical results

According to the classification based on the total dose and application length of OXA injection, we found that there was significantly reduced tissue GPX activity in rats that were given higher-dose/long-term OXA compared to the sham group. The mean GPX activities were 0.66 U/mg in the sham group, 0.74 U/mg in the short-term groups, and 0.74 U/mg in the long-term groups (Table 4). The tissue GPX level was significantly higher in the lower-dose/short-term group compared with the sham group (p = 0.049).

Discussion

In our study, we found that the rats that received short-term OXA administration had significantly higher GPX activity in the lung tissue. Initially this suggests that the anti-oxidant system was activated and during this period, drug therapy was counteracted by the lungs. Meanwhile, the antioxidant system of the lungs was compromised with the continuation of therapy. When the chronic therapy was discontinued, in other words, after the elimination of the effect that created oxidative stress (despite the time elapsed) the impaired antioxidant balance could not be restored. No histopathological findings were detected as a response to the increase in the antioxidant system during the initial period. In rats that received higher-dose/long-term OXA therapy, histopathological findings indicating chronic pulmonary toxicity such as increased interstitial pneumonia and interstitial/intra-alveolar macrophage and eosinophil counts proceeded consistently with the decrease in lung tissue GPX activity.

In the first efficacy and safety studies of OXA, it was reported that pulmonary toxicity did not develop with the exception of hypersensitivity reaction and dyspnea [17]. However, pulmonary damage was reported in patients with colorectal cancer, who recently received the FOLFOX regimen, composed of OXA, 5-fluorouracil (FU) and folinic acid (FA) [11, 12]. Muneoka et al. [18] reported that pulmonary toxicity did not recur clinically when they administered 5-FU and FA without OXA to patients who had developed pulmonary toxicity after the FOLFOX regimen. In addition, due to the lack of data related to pulmonary toxicity in previous studies related to 5-FU and FA, it was believed that pulmonary side effects in these cases were associated with OXA [18]. In addition, Yague et al. [19] reported pulmonary toxicity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who were given OXA alone. In a case series published in 2012, Prochilo et al. [20] reviewed 30 gastric or colorectal cancer patients and discussed OXA-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary fibrosis was not observed in other treatment regimens except for OXA alone (n = 1), FOLFOX regimen combined with bevacizumab (n = 2), OXA combined with capecitabine and bevacizumab treatments (n = 1) [20]. The number of administered chemotherapy cycles varied between 1 to 13 and the OXA dosage and the median number of chemotherapy cycles showed a slight difference between those who developed pulmonary fibrosis and those who did not [20]. However, the limitation of this study was that the risk factors and the number of administered OXA cures in this analysis involving the previous 30 cases could not be determined clearly [20, 21].

Histopathologically organized pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia were reported in some of the patients with colorectal cancer who received the FOLFOX regimen [11, 12]. Additionally, Wilcox et al. [21] presented evidence of pulmonary toxicity in three patients treated with the FOLFOX regimen who developed interstitial lung disease following chemotherapy. Nevertheless, it is not known whether the incidence of interstitial lung disease development is due to OXA-induced pulmonary toxicity [21].

Although some mechanisms leading to pulmonary toxicity associated with various chemotherapeutics such as bleomycin, mitomycin, busulfan, and taxanes are well understood, it is not yet clear which mechanisms cause OXA-induced pulmonary damage. It was reported that OXA causes GSH depletion and this may be the underlying mechanism of liver damage resulting from hepatic sinusoidal obstruction. Similarly, GSH is an important antioxidant small molecule for human lungs and it may exhibit a protective effect against pulmonary damage by the oxidant/ROS. From this point of view, it may be extrapolated that OXA can cause pulmonary toxicity through GSH depletion in pulmonary tissue [21]. In addition to the significant reduction in pulmonary GPX activity that we observed in the present study, all of the previous reports support the histopathological findings indicating the incidence and progression of chronic toxicity.

The most striking finding of the present study was the substantial increase in eosinophils and interstitial/intraalveolar macrophages in the histological examination of the group treated with high-dose/long-term OXA. Gagnadoux et al. [22] have also reported a case with OXA-induced eosinophilic pulmonary damage. Eosinophils are granulocytic cells, which secrete various cytokines, chemokines, and mediators [23]. They become hyper-granulated directly by oxidative stress products and indirectly by inflammatory cells. They also induce tissue damage as a result of granule degradation [24]. This event may be explained with the adaptation of eosinophilic activation of ROS that takes place in the lungs. Based on our results concerning the tissue GPX activity, diminished GPX activity in pulmonary tissue may indicate that the oxidative stress in the lung tissue caused by ROS occurring in association with OXA may also create eosinophilic damage.

Limitations

The most important limitation of our study was the inability to examine pulmonary tissue by electron microscopy, which was due to technical problems and financial limitations. Therefore, further detailed studies incorporating advanced electron microscopy and evaluating various molecular mechanisms will enable us to better identify and understand OXA-induced pulmonary toxicity. This in turn will result in improvements in the implementation of the therapy and the management of side effects.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the mechanism of OXA-induced pulmonary toxicity, which can be diagnosed clinically and radiologically after excluding other potential causes, is not clear yet. This animal study could provide evidence both histologically and biochemically that the long-term administration of OXA can lead to pulmonary toxicity and result in a decrease in lung GPX activity compared with the control group and the short-term implementation of OXA. This may indicate that the increased eosinophil presence in pulmonary tissue due to OXA implementations in the long term may be one of the factors that lead to pulmonary toxicity.