INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia (SCHI) is one of the mental disorders associated with the significant impairment of social functioning, as well as numerous somatic comorbidities, including metabolic ones: obesity, dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus (especially type 2). At the core of this state lay the side effects of applied psychopharmacotherapy, poor dietary habits, lack of physical activity and low social drive [1]. Therefore, it seems that the group of patients suffering from SCHI is also particularly vulnerable to the development of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), the liver equivalent of the metabolic syndrome (MetS) (Figure I) [2]. The several epidemiological studies conducted to date have confirmed this hypothesis, indicating that the prevalence of fatty liver disease among subjects with SCHI may vary from 22.44% to as much as 70.8% [3-5].

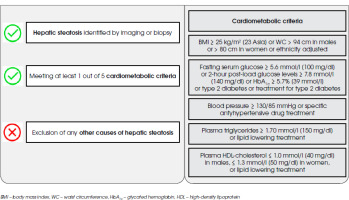

Figure I

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) diagnostic criteria according to multisociety Delphi consensus statement from 2023

MASLD, previously known as a non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), is a systemic disease associated with numerous hepatic (liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver failure) and extrahepatic (increased cardiovascular risk and incidence of extrahepatic neoplasms) complications [6]. Thus, it constitutes a significant clinical problem in everyday practice. It is postulated that insulin resistance, dysfunction of adipose tissue and associated adipokines, lack of physical activity, overweight or obesity caused by a high-calorie diet, genetic factors and oxidative stress may contribute to its development [7]. Nevertheless, the pathogenesis of MASLD remains unclear.

Recently, particular attention has been paid to the role of ferroptosis, a novel form of cell death, as one of key aspects in the development, progression and clinical outcomes in a number of diseases, such as cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal and gastrointestinal ones, including fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis [8]. Interestingly, the same process has been identified in the pathogenesis and course of SCHI [9, 10]. In this review, we will attempt to show the specific role of ferroptosis in the possible development and progression of MASLD among patients with SCHI. It will be accompanied by a consideration of the probable causes of the associations that occur in this context.

THE FERROPTOSIS MECHANISM

Ferroptosis, a form of iron-dependent programmed cell death, consists of two basic processes:

Iron overload

Iron, through its ability to catalyze the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), may cause oxidative stress. This occurs during the Fenton reaction. Physiologically, the complex of Fe3+ and transferrin is recognized by surface transferrin receptor 1, and then internalized through endocytosis into cells. Next, Fe3+ is reduced to a more stable form, Fe2+ ion, which is stored in the form of ferritin. When an excess amount of intracellular Fe2+ is reoxidized to Fe3+, the iron-efflux protein solute carrier family 40 member 1 (SLC40A1, known also as ferroportin 1) extrudes Fe2+ into the extracellular compartment. Thus, disorders associated with impaired cellular iron influx or removal may lead to an iron overload [11, 12].

Lipid peroxidation

The process of lipid peroxidation can be divided into three phases: initiation, propagation and termination. However, the specific mechanisms involved in each stage remain only partially understood.

In order for lipid peroxidation to be initiated, a bis-allylic hydrogen atom in between two carbon- carbon double bonds has to be abstracted from polyunsaturated fatty acyl moieties, present on phospholipids. It may occur through alkoxyl radicals in lipids or hydroxyl radicals, with the presence of iron as a catalyst [13]. An enzymatic pathway for the initiation of lipid peroxidation, using lipoxygenases and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase, is also possible [14, 15]. In particular, phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine, important components of the phospholipid cell membrane, seem to play a major role in this process, as has been shown in recent studies [16]. In this context, the role of membrane- remodeling enzymes, such as acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long chain family member 4 and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferases is emphasized, as they contribute to the synthesis of high levels of PUFAs and the diversification of the composition of fatty acids in biological membranes [17, 18].

This leads to the phospholipid carbon-centered radical formation and its reaction with the oxygen. Therefore, lipid peroxyl radicals are produced, which in turn combine with hydrogen from other polyunsaturated fatty acids and form lipid hydroperoxides, as well as new lipid radicals. A vicious cycle of the next radical-mediated reactions propagation appears. All in all, this may result in the cellular organelles, as well as cells membranes destruction [13].

Regulatory pathways associated with ferroptosis

Several regulatory pathways have been discovered which may affect the occurrence and severity of ferroptosis.

The cysteine–glutathione–glutathione peroxidase 4 axis

Cellular cystine/glutamate antiporter (also known as system xc–) provides a sufficient supply of a substrate, cystine, necessary for the glutathione (GSH) synthesis, which acts as the main antioxidant in the human organism. To synthesize GSH, it is also necessary to reduce cystine to cysteine. This occurs through thioredoxin reductase 1 activity. Additionally, the cellular activity of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) prevents from the accumulation of cytotoxic lipid peroxides, reducing hydroperoxides from phospholipids and cholesterol while oxidizing GSH. GSH is regenerated via glutathione-disulfide reductase [19].

The coenzyme Q10–ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 axis

In turn, the ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 is protective against ferroptosis regardless of the cellular GSH level, GPX4 activity level, or status of p53. It acts by catalyzing the reduction of ubiquinone to ubiquinol through NAD(P)H, thus inhibiting lipid peroxidation [20].

The cyclohydrolase-1–tetrahydrobiopterin–dihydrofolate reductase axis

Another possible pathway that regulates ferroptosis is the guanosine 5´-triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1-tetrahydrobiopterin-dihydrofolate reductase axis, insufficient activity in which may lead to excessive ROS production [20].

Other pathways

In addition, several other pathways or molecules, especially those associated with lipid metabolism alternations, autophagy, iron cellular storage and mitochondrial dysfunction, have been emphatically noted in the regulation of ferroptosis: the ATG5-ATG7-NCOA4 pathway, p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway, heat shock protein beta-1, iron response element binding protein 2, and E-cadherin- NF2-Hippo-YAP pathway, as well as dihydroorotate dehydrogenase-ubiquinol system, glucose-regulated AMPK signalling and glutamine, mevalonate or sulfur pathways [13, 21-24].

The dual role of P53 signaling (both promoting and inhibiting the process of ferroptosis) is also emphasized [25].

THE GENETIC AND MOLECULAR APPROACH TO MASLD AND SCHIZOPHRENIA

The genetic basis of SCHI and MASLD seems important to understanding the pathogenesis of both diseases. Recent scientific reports indicate that certain common genes may have a significant role in their development and clinical course. Particular attention has been paid to altered genes, the expression of which leads to a predisposition to ferroptosis and increased oxidative stress. Some of them may act as drivers, inhibitors or regulators of these processes. In Feng et al.’s study, three hub genes – TP53, VEGFA and PTGS2 – were found to be significantly associated with SCHI, and thus to be ferroptosis-related markers of the disease [26]. Interestingly, the same genes have been identified in the pathogenesis of MASLD [27-29]. In turn, the role of another ferroptosis-related gene, ATG7, has also been emphasized in the pathogenesis of both conditions [30, 31] (Table 1).

Table 1

Ferroptosis-related genes, coding proteins and their role in ferroptosis

| Name of the gene | Coding protein | Driver/Inhibitor/marker | Role in ferroptosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATG7 | Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme ATG7 | Driver | Role in autofagosome/autolysosome formation [32, 33] Takes part in nuclear receptor coactivator 4-mediated ferritinophagy which leads to an increase in intracellular labile iron levels [34] |

| PTGS2 | COX-2 | Marker | ROS production Upregulation as a marker of ferroptosis Possible role in mediating ferroptosis in neural cells [35-37] |

| TP53 | P53 | Driver | Causes a decrease in ferrostatin-1 level, which acts as a ferroptosis inhibitor Inhibits cellular cystine uptake Suppresses GPX 4 activity Impairs glutamine metabolism [38-40] Loss of P53 leads to plasma-membrane-associated dipeptidyl-peptidase-4-dependent lipid peroxidation with the subsequent ferroptosis process [41] |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | Marker | Increased expression as a marker of ferroptosis Inhibition of SLC7A11 promotes the expression of VEGF [42, 43] Lipid peroxidation products induce specific isoforms expression [44] |

In terms of above-mentioned scientific findings, it seems that both MASLD and SCHI may share similar genetic pathways connected with oxidative stress and ferroptosis. This brings indirect evidence that the SCHI population may be vulnerable to fatty liver disease, with a subsequent development of liver fibrosis, in the mechanism of genetic susceptibility leading to hepatocyte ferroptosis. Nevertheless, future studies assessing the genetic markers of MASLD and SCHI should improve our understanding of the possible connections between these two states.

IMPACT OF ANTIPSYCHOTICS ON THE FERROPTOSIS PROCESS

Antipsychotics (APs) are widely used medications in the treatment of SCHI. Their application is associated with numerous side effects, including those which are metabolic, extrapyramidal, and involve the endocrine system [45, 46]. Emerging data suggest that their application may also impair iron metabolism and systemic redox balance [47, 48]. However, their impact on the ferroptosis process in the context of fatty liver disease and the development of hepatic fibrosis has not yet been deeply investigated.

Iron overload

In the study by May et al. [49], it was pointed out that clinically relevant exposure to APs caused a significant increase in total iron concentrations in the liver, consistent with changes in gene expression in pathways associated with the regulation of iron homeostasis coincident with NAFLD. It is postulated that at the core of this state may lie the ability of APs to decrease the density of membrane cation channels and transferrin co-receptor, homeostatic iron regulator protein (HFE protein). Moreover, an impairment in the formation of endosome and vesicle may lead to disturbed cellular iron uptake, resulting in an accumulation of extracellular iron in the liver. This hypothesis is partially justified by the research findings of Keleş-Altun et al. [50], who observed that chlorpromazine-equivalent doses of APs correlated positively with ferroportin levels, which may be an indicator of tissue iron overload. Another possible pathway leading to iron-overload during the treatment with APs was presented by Bai et al. [51], who found that haloperidol may aggravate the accumulation of cellular Fe2+ in hepatocytes, through inducing the expression of the sigma 1 receptor and other regulators involved in the ferroptosis process.

Lipid peroxidation

Dietrich-Muszalska and Kolińska-Łukaszuk [52] evaluated the effect of selected APs at doses recommended for the treatment of an acute episode of SCHI, on lipid peroxidation in vitro. They revealed that risperidone, ziprasidone and haloperidol intensified the process of lipid peroxidation, presenting a strong prooxidative effect. Conversely, quetiapine, olanzapine and high doses of clozapine acted as antioxidants. Aripiprazole did not induce statistically significant changes in plasma lipid peroxidation products. However, research results so far have been inconclusive. Andreazza et al. [53] indicated that not only haloperidol, but also clozapine may induce excessive lipid peroxidation in the brain, as well as in the liver tissue, on the basis of animal models. Similar results were observed by Reinke et al. [54]. In turn, Noto et al. [55] revealed antioxidant properties, by reducing the intensity of lipid peroxidation, of risperidone in drug-naïve, first-episode SCHI patients.

Nevertheless, it is hypothesized that APs may lead to excessive lipid peroxidation through several pathways:

indirectly, causing weight gain and fat accumulation,

directly, suppressing the activity of enzymes or molecules engaged in the oxygen redox stability maintenance, or their expression with a subsequent limitation of their synthesis.

In the study by An et al. [56], conducted on 89 long-term patients with SCHI, it was found that subjects with a high body mass index have higher levels of lipid peroxidation products levels in comparison to patients with a normal BMI. These findings are consistent with the current knowledge on the relationship between obesity, dyslipidemia and oxidative stress, as mitochondrial dysfunction, often observed in obese individuals, may lead to increased electron transport chain activity with the subsequent production of ROS [57]. Therefore, it can be speculated that those APs with the highest obesogenic potential may contribute to the greatest extent to the intensification of the lipid peroxidation process (Table 2).

Table 2

The obesogenic potential of chosen antipsychotic medications [45]

In turn, Lin et al. [58] indicated that the use of APs may also have an impact on peripheral expressions of the system xc- subunits, leading to oxygen redox instability. In another study, it was noted that such APs as volanserine, amisulpride and risperidone, may lead to the downregulation of the expression of GPX4 in human cells, which contributes to ROS production, lipid peroxidation and, thus, the initiation of ferroptosis [59].

All things considered, given the fact that the use of APs is the basic form of SCHI treatment, it seems important to be aware of the possible impact of these medications on iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation. More studies in this field are highly recommended, to assess properly their modulatory impact on these processes.

IMPACT OF DIETARY HABITS

As previously mentioned, risk factors for the development of MASLD include obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia [60, 61]. These features are often associated with poor dietary habits such as excessive calorie intake or high fructose consumption [62]. Zelber-Sagi et al. [63] observed that the diet of obese individuals with NAFLD mainly consists of fat and carbohydrates.

Interestingly, emerging data suggest that the same issue may also apply to the SCHI population. It is assumed that only 10.7% of patients with SCHI spectrum disorders have a healthy pattern of dietary habits [64]. A cross- sectional descriptive study conducted by Zurrón Madera et al. [65] showed that SCHI subjects’ diets are mostly based on fatty meat, with insufficient servings of fish and supply of such vitamins as A, D, E, K1, C and folic acid. Sorić et al. [66] also observed that the daily frequency of fruit and vegetable intake in this group was below the recommended level. Another study has drawn attention to the fact that too low a percentage of daily energy comes from the consumption of carbohydrates and polyunsaturated fatty acids, and too high a percentage from protein and total fat intake, especially saturated fatty acids [67, 68].

Based on abovementioned findings, it is highly probable that there is a link between SCHI and MASLD in terms of the high-fat diet (HFD), excessive fructose consumption and insufficient intake of antioxidants. Recent findings suggest that poor dietary habits may lead to iron overload and excessive lipid peroxidation – therefore, the ferroptosis process may, at least partially, explain the co-occurrence of fatty liver disease with subsequent fibrosis and SCHI.

Iron overload

In numerous studies, HFD and high-fructose consumption have been identified as triggers for the development of dysmetabolic iron overload syndrome in the liver, probably independently of changes in dietary iron intake or hepcidin activity [69-71]. Several processes may lie at the core of the occurrence of this condition: increased expression of the major iron uptake protein, transferrin receptor-1, as well as upregulation of the intracellular iron sensor – iron regulated protein-1 [69].

Lipid peroxidation

Diets rich in saturated fatty acids and over-refined sugars significantly contribute to excessive lipid peroxidation in various tissues, including the hepatic [72]. Excessive fat accumulation within the liver leads to the stimulation of mitochondrial β-oxidation. As already mentioned, this results in the excessive activation of cytochrome c oxidase electron flow, with subsequent ROS accumulation within cells [73].

It is worth noting that the ROS generated may also cause an outburst of systemic low-grade inflammation, which acts as a prooxidative factor [74]. Related disrupted neural transmission (through the brain-adipose tissue axis) in terms of sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation results in a decrease in GSH and nitric oxide concentrations and their synthesis within hepatic tissue [75]. Thus, a vicious circle between inflammation and ROS production is formed [76].

In the context of oxidative stress balance, an insufficient quantity of antioxidants as contained in vegetables or fruits in the diet, also leads to the predominance of organism’s pro-oxidant compounds. Hence, their role in preventing lipotoxicity initiation is unquestionable [77].

THE ROLE OF INTESTINAL PERMEABILITY

Intestinal permeability, also known as a “leaky gut” syndrome, is a condition in which gut integrity disruption appears. It is caused by various factors, affecting tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells [78]. As a result, undigested food particles, microorganisms or their metabolites are allowed easy entry into the bloodstream [79].

Dysfunction of the intestinal barrier has been identified in the pathogenesis of various diseases. Recent studies have shown that leaky gut syndrome is not rare among SCHI patients, as significantly higher rates of „leaky gut” indices, in comparison to healthy controls, were found [80]. Additionally, intestinal permeability was significantly associated with the presence of subclinical inflammation markers. On the other hand, leaky gut syndrome may also contribute to the occurrence of fatty liver disease. Because of the anatomical connection between the gut and liver through the portal vein, 70% of blood supply comes from the intestines. Thus, the liver is the first organ to be exposed to the majority of bacteria, their metabolites and endotoxins [81]. Due to intestinal hyperpermeability, these microorganisms (especially Gram-negative bacilli) or their metabolism products easily penetrate intestinal mucosa, reaching the liver, and may promote inflammation within the liver tissue, with the subsequent development of NASH and hepatic fibrosis [82].

As has been shown, leaky gut syndrome may serve as a link between SCHI and MASLD. However, this possibility has not been explored widely yet. Recently, particular attention has been paid to the ferroptosis process as a possible molecular basis for intestinal permeability [83]. In addition, it seems that the relationship between intestinal permeability and ferroptosis is multidirectional. On the one hand ferroptosis has been supposed to trigger the development of intestinal permeability; conversely, „leaky gut” may lead to ferroptosis via iron overload and the initiation of excessive lipid peroxidation.

Ferroptosis as an initiating factor in the development of intestinal permeability

It has already been noted that subjects with SCHI had significantly higher ferroportin protein levels in comparison to healthy controls, which increased expression is seen in states of iron accumulation within cells and tissues [50, 51]. Surprisingly, ferroportin is a transmembrane protein found in the largest amounts on intestinal enterocytes. Thus, it may be assumed that these cells are the first to experience iron overload. An excessive amount of cellular iron ions may lead to ROS production, resulting in epithelial cells and tight junctions’ destruction. Thus, it contributes to the intestinal barrier hyperpermeability and systemic inflammatory response [84].

Impact of intestinal permeability on ferroptosis

To date, there is lack of research assessing the impact of intestinal permeability on systemic iron overload. However, leaky gut syndrome promotes low-grade inflammation and pro-inflammatory cytokines can regulate the synthesis of ferritin, which is responsible for iron storage in cells and tissue [85]. Moreover, inflammation is associated with the subsequent production of ROS, which trigger lipid peroxidation in various tissues, including the hepatic [86].

Therefore, through these pathways, “leaky gut” may contribute to the initiation of ferroptosis in hepatocytes. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of intestinal permeability on the development of fatty liver disease development in connection with ferroptosis.

POSSIBLE PREVENTIVE AND THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES TO MASLD

Preventive actions

There are no specific methods of ferroptosis prevention in the context of the development of MASLD. However, the reduction of cardiometabolic risk factors may prevent from disturbances in iron homeostasis and excessive lipid peroxidation occurrence. Thus, it is important to ensure regular monitoring of body mass index, blood pressure, lipid profile and serum glucose concentration, especially during long-term treatment with APs with obesogenic potential and causing other metabolic repercussions including dyslipidemia and the impairment of fasting glucose or glucose tolerance. Moreover, liver function tests, ultrasound scan of the liver and the Fibrosis-4 Index should be performed periodically in all psychiatric patients. Psychiatrists should encourage their patients to make lifestyle modifications and change dietary habits in favour of polyunsaturated fatty acids and antioxidants [87]. It also seems reasonable to administer psychotropic medications with the lowest risk of metabolic side effects (e.g. dopamine D2/3 receptor partial agonists), or in the form of long- acting injections, as well as at the lowest effective dose [88].

Therapeutic actions

According to numerous international consensus statements, a therapeutic regimen should begin with weight reduction through increasing physical activity and making dietary changes [89, 90]. It is also important to manage properly other somatic comorbidities that may contribute to the development of MASLD, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia or diabetes [91]. In cases of biopsy-proven non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), vitamin E may bring therapeutic benefits [92]. In turn, among subjects with NASH and concomitant diabetes, it is recommended to administer thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone) or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists [93-95]. Interestingly, in 2024, U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved resmetirom for the treatment of adults with NASH with moderate to advanced liver scarring. Significant efficacy on hepatic fibrosis and steatosis reduction has also been confirmed for sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors [96].

In terms of ferroptosis, several studies have indicated that the use of iron chelators (e.g. deferoxamine, deferiprone and deferasirox) may be beneficial in the treatment of iron overload [97]. Promising results were also observed in case of phlebotomy. However, its usefulness seems to be limited only to hemochromatosis [98].

In the context of excessive lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, particular antioxidants such as liproxstatin-1 and active forms of vitamin E have been suggested as a possible therapeutic approach in liver diseases. Nevertheless, their efficacy has been confirmed only on the basis of animal models [99].

CONCLUSIONS

Ferroptosis appears to play a key role in the occurrence and possible progression of MASLD among the SCHI population. Genetic susceptibility, poor dietary habits, the issue of intestinal permeability, as well as applied psychopharmacotherapy may contribute to the development of this process. Nevertheless, further empirical research is needed to assess the importance of the body’s iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation in the pathogenesis of fatty liver disease. Moreover, finding a possible biomarker associated with ferroptosis would allow for the speedy identification of a subpopulation of SCHI patients at particular risk of developing MASLD with subsequent liver fibrosis. The proper diagnosis of MASLD and taking of appropriate therapeutic steps become even more important in the context of the global burden of metabolic disorders, as patients with SCHI often receive inadequate health care and many serious somatic illnesses remain undiagnosed and untreated.