Introduction

The fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) is one of the most characteristic and widely recognized species of mushrooms in the world. Taxonomically, it is classified in the phylum Basidiomycota, order Agaricales, and family Amanitaceae. The cap of the species of mushroom usually reaches a diameter of 4 to 21 cm, is characterized by an intense red color, and is covered with white warts [1]. Its characteristic appearance, wide range of occurrence, and historical use in mystical rites and folk medicine have made it an important part of cultural consciousness for many generations. Despite its popularity, the chemical profile of A. muscaria has not yet been fully understood. Even though many of its key components have been identified and described, the existing research does not yet allow for a comprehensive understanding of the properties of the species or its effects on the human body.

The fly agaric is widely considered a poisonous species, with patients reporting to the hospital after consuming it with symptoms such as confusion, dizziness, agitation, and ataxia. Less frequently, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, tachycardia, bradycardia, hypertension, hypothermia or hyperthermia and metabolic acidosis may occur, and fatal poisonings also occur [2]. Despite the high social awareness of the toxicity of the fly agaric, a certain trend towards its consumption has been observed over the last decades, mainly for medicinal purposes. Interest in the mushroom is increasingly common among so-called “influencers”, i.e. public figures who are active in social media, which significantly translates into shaping public attitudes and opinions.

Historically, for centuries, the mushroom has been used in natural therapies, for example in the treatment of rheumatism and dysentery [2]. Recent studies indicate that A. muscaria may be potentially useful in the fight against conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, autism spectrum disorders, and even addiction. It is important to note that the use of A. muscaria for medicinal purposes is currently not approved by any regulatory bodies [3].

The mushroom is also used recreationally by people looking for alternative experiences, because it contains compounds with strong psychoactive effects. Taking the right dose causes hallucinogenic effects, perceptual changes, mood changes and coordination disorders. Consumption of the fly agaric is usually not preceded by a consultation with a doctor. According to research, interested people obtain knowledge about the method of preparation and dosage mainly from the Internet, and consumption usually takes place at home [2].

It can therefore be stated that the use of A. muscaria is most often amateur, which, given the toxicity of it, poses a significant health risk. Due to the growing popularity of using A. muscaria and the simultaneous lack of sufficient medical knowledge about the effects of the mushroom on the human body, the risk of poisoning is increasing in the society. There are also no legal regulations limiting its consumption and trade on the market. Placing greater emphasis on conducting detailed scientific research and developing appropriate legal regulations that will ensure consumer safety is a very important task faced by scientists and government officials. At the same time, constantly appearing reports on certain health-promoting properties of the fly agaric suggest that the possibility of using it in the pharmacotherapy of diseases should not be underestimated.

Aim of the work

The aim of the paper is to summarize the current state of knowledge regarding the properties of the fly agaric based on the analysis of the latest scientific publications on both negative and positive implications of the action of A. muscaria on human health, to discuss the chemical profile with the most important components, to characterize the reasons for interest in the species, to draw attention to the opportunities and threats associated with its use, and to describe the historical use of the mushroom.

Methods

The literature review was conducted by analyzing domestic and foreign publications available in the PubMed, Elsevier ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, ResearchGate, Academia databases using the following keywords: Amanita muscaria, mycotoxins, neurotoxins, mycology, muscimol. The search results for keywords were very numerous, but due to the concern for the validity of the cited information, selection was made based on the criterion of the publication date. Emphasis was placed on papers no older than 5 years. All co-authors were responsible for searching and analyzing the literature and for the interpretation of data.

Literature review results

Historical uses of the fly agaric

The fly agaric A. muscaria has been known for its hallucinogenic and narcotic properties in many cultures for hundreds of years. In the sources we can find information about the use of the fly agarics mainly by the Paleo-Asian peoples living in eastern and north-eastern Siberia. The Koryaks and Chukchi were aware of the poisonous properties that the fly agaric showed without proper preparation. The mushroom was used for both religious and relaxation purposes [1]. Shamans used it to achieve a state of trance, and laypeople used it as a relaxing and psychedelic agent [2]. In the tradition of the people of Siberia, there was an interesting practice: a shaman, by consuming the mushroom, acted as a “filter”, because his urine contained psychoactive substances of lower toxicity. The other participants in the ritual drank the urine, thus avoiding the more severe side effects associated with direct consumption of the mushroom. It was not only humans who were sensitive to the effects of the fly agaric. The inhabitants of Siberia, who were aware of that, recognized the symptoms of the fly agaric intoxication in a reindeer, slaughtered the animal and ate the meat, which still had psychoactive properties. In Eastern Europe, the mushroom was used as fly poison, as it was widely believed to be poisonous to flies. The mushroom did not kill the insects, but put them into a state of lethargy, lasting about three days, they were easily removed from homes. Folk use of A. muscaria was recorded in Lithuania, where the mushrooms were mixed with vodka during weddings. Lithuanians exported the fly agarics to Samia in the Far North, where they were used in shamanic rituals.

Bioactive ingredients

The fly agaric contains compounds that individually exhibit a range of different biological activities [1]. Importantly, the species does not contain amatoxins [4], highly toxic compounds found in many mushrooms from the Amanita family, including the death cap mushroom. The lethal dose of amatoxins is only 0.1-0.3 mg per kilogram of body weight. For example, just one 40 g death cap mushroom containing 5-15 mg of amanitin α can lead to death. The toxic effects of A. muscaria are mainly attributed to two psychoactive isoxazoles: ibotenic acid and muscimol. Both substances act as “false” neurotransmitters [5], which means that due to their structure, they imitate key neurotransmitters, i.e. substances responsible for transmitting signals between nerve cells in the synapse [2]. It is precisely with its effect on the nervous system that the toxicity of the fly agaric is most closely related. A fly agaric fruiting body weighing 50-70 g (fresh weight) may contain about 6 mg of muscimol and up to 70 mg of ibotenic acid. Thus, one mushroom fruiting body contains sufficient amounts of alkaloids to produce psychoactive effects in an adult human. The relative percentages of muscimol and ibotenic acid in the dry weight of fresh fruiting bodies (caps) are 0.17-0.35 and 0.78-2.60, respectively [6] (Table 1).

Table 1

Percentage of active substances in the dry mass of spores and fruiting bodies of A. muscaria

| Active substance | Spores | Fruiting bodies |

|---|---|---|

| Muscimol | 0.05-0.09 | 0.17-0.35 |

| Ibotenic acid | 0.47-0.61 | 0.78-2.60 |

| Muscarine | 0.001-0.003 | 0.005-0.008 |

[i] Notes: Own elaboration based on Okhovat et al. [6]

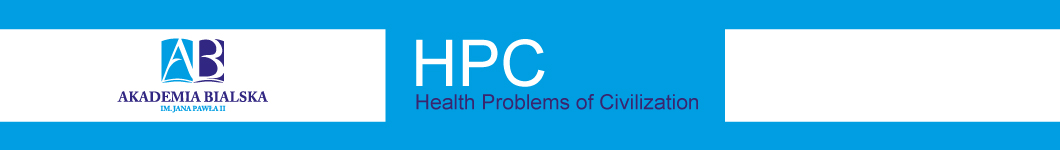

In the acidic environment of the stomach, ibotenic acid is decarboxylated to muscimol, thereby increasing its concentration in the digested dose of the fly agaric. Other components have also been isolated from the mushrooms in lower concentrations, including muscazone, choline, acetylcholine, betaine, muscarine, hyoscyamine, atropine, scopolamine, and bufotenine, they may contribute to the general toxidrome as well as to the occasionally observed cholinergic and anticholinergic symptoms [4]. A. muscaria also contains a myriad of other compounds, including antioxidants, pigments, and polysaccharides [7] (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Chemical structure of the most important active substances contained in A. muscaria Notes: A – muscimol, B – ibotenic acid, C – muscarine; own elaboration based on National Center for Biotechnology Information [8].

Muscimol

Muscimol is a key compound in A. muscaria that affects the nervous system. It has psychotropic properties and can cause acute changes in perception, mood, cognition, and behavior. Like alcohol and benzodiazepines, muscimol is a GABA receptor agonist that exerts an inhibitory effect on the central nervous system, primarily in forebrain areas such as the caudate nucleus, putamen, thalamus, and hippocampus [7]. By stimulating the GABAergic system, it affects the transmission of neurotransmitters. Serotonin, dopamine and acetylcholine levels increase, and noradrenaline levels decrease [9]. Even 15 mg of muscimol can cause severe poisoning [10]; the symptoms it causes in the body include dizziness, nausea, fatigue, a feeling of weightlessness, visual and auditory hypersensitivity, space distortion, unconsciousness of time and colorful hallucinations. Even though some of the effects mentioned are similar to those associated with psilocybin, muscimol, unlike psilocybin, does not interact with 5-HT2A serotonin receptors [7], hence the fly agaric affects the human central nervous system differently than psilocybin-containing mushrooms Results of studies show that among all the developmental stages of A. muscaria, the maximum concentration of muscimol (1210 mg/ml) was found in the developmental stage of young mushrooms [11].

Ibotenic acid

Ibotenic acid used to be called premuscimol because it is decarboxylated to muscimol during drying and in the acidic environment of the stomach. Ibotenic acid is a close analogue of the neurotransmitter glutamic acid (there is a structural similarity), acting as a nonselective glutamate receptor agonist. It is also a strong agonist of the NMDA receptor and metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) of groups I and II, except group III. Ibotenic acid is also a weak agonist of the AMPA receptor and kainate receptors (KAR). Its action is mainly focused on NMDA and trans-ACPD receptors in the central nervous system. Ibotenic acid is classified as a substance with neurotoxic and psychotropic potential, it induces psychoactive effects in humans at a dose of 50-100 mg. An analogous psychoactive effect corresponds to a dose of 10-15 mg of muscimol [9]. Unlike muscarine, ibotenic acid readily crosses the blood-brain barrier via an active transport system and exerts its effects primarily on the central nervous system, where it acts as a neurotransmitter agonist [1].

Muscarine

The name of the alkaloid comes directly from A. muscaria, because it was from the species that it was first isolated. It took place in 1869 and for decades it was believed that muscarine was the main active ingredient of the fly agaric [12]. Mushrooms that produce muscarine pose a serious threat to human health, because its consumption can lead to circulatory collapse and even death. Muscarine is one of the most toxic metabolites found in mushrooms [13]. As a nonselective acetylcholine agonist, it acts directly on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the parasympathetic nervous system, one of the three parts of the autonomic nervous system. Once attached to a cholinergic receptor, it is not broken down by cholinesterase, which means that it acts on neurons for longer than acetylcholine, which in turn is related to its toxicity. Parasympathetic nerves include smooth muscle and glands, which allows muscarine to affect various organs. The compound is unable to cross the blood-brain barrier or the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier, preventing potential effects on acetylcholine receptors in the central nervous system. Although muscarine is present in trace amounts (0.02% dry weight) in the fruiting bodies, it is the primary factor responsible for autonomic symptoms following fly agaric ingestion, particularly those related to the gastrointestinal system. The symptoms include sweating, salivation, lacrimation, bradycardia, diarrhea, and fatigue. In terms of biological activity, muscarine, a neurotransmitter agonist, exhibits a broad spectrum of action on various neurons and endocrine cells [12].

Reasons for the growing interest in A. muscaria

Although the fly agaric has been used by humans for centuries, access to the Internet has popularized the phenomenon. Some people, due to the lack of access to traditional drugs, seek alternative ways to get high [2], but the reasons for consuming the fly agaric are not focused solely on the psychedelic properties. Today, A. muscaria enjoys a reputation as a natural remedy for several ailments, such as sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, and is sometimes used as a painkiller, an anti-swelling, and anti-inflammatory agent. One case study described involved a woman, a Ukrainian immigrant living in the UK, who had been using the mushroom as a sedative. She was admitted to the emergency department in the early hours of the morning in a state of acute confusion. In this woman’s country of origin, the fly agaric is widely considered an herbal remedy for sleep and stress management. She had purchased 20 g of dried mushrooms via a social media site. She reported consuming 0.5 g of a red-orange mushroom daily, regularly in the evenings for the past 2 weeks. The night before her admission to the hospital, she had eaten approximately 1 g of dried mushrooms before going to bed because her mother, who was still in Ukraine, had told her that their hometown was under heavy fire. She woke up 2-3 hours later intoxicated with extremely vivid visual and auditory hallucinations, including the belief that her deceased grandmother was talking to her, out-of-body experiences, and finally the feeling that she had died and been reborn [14].

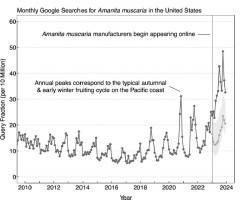

Over the past few years, commercially manufactured products have entered the U.S. market, including harvested the fly agaric mushrooms and products containing isolated muscimol. Product offers include candy-flavored muscimol gummies, dessert-flavored muscimol vaporizers, and cannabis flower muscimol pre-rolls. Google searches for Amanita muscaria increased by 114% between 2022 and 2023, and were 97.4% (95% CI: 78.1-118.3) higher than the expected seasonal trend for 2023 [7], as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Increase in monthly searches for the term “Amanita muscaria” in Google in the USA over the past years [7]

A survey published in 2023 showed that the most common reasons for taking fly agaric mushrooms in the entire sample were expected healing effects, spiritual needs, and increased mental capacity. Half of the respondents indicated curiosity as the reasons for using them, and about 33% indicated relaxation. Seeking pleasure is the reason declared by every fourth respondent. 16% of the respondents take fly agaric mushrooms because of problems in their personal lives. The least common source of knowledge about the mushroom (only 3% of respondents) is the attribution of the use to peer pressure [2]. In the same study, respondents were asked about their sources of knowledge about the fly agaric. The vast majority of respondents used resources available on the Internet. The second most common source of knowledge is scientific publications, used by about half of respondents. Close ones – friends, family, acquaintances – are a source of knowledge about the mushroom for about 44%. The least common sources of information about the mushroom were “nature” and experience.

Dosage and methods of consumption

The number of mushrooms consumed, the way they are prepared, and the time and place of collection can affect their toxicity. There are many uncertainties regarding how the active substances of the fly agaric affect the physiology of the body in relation to the different methods of preparation and consumption of the mushroom. Concentration of individual chemical compounds changes during the development of the fly agaric. The dose of ibotenic acid and muscimol resulting in psychotropic effects is known, therefore knowledge of the amount of the substances in the mushroom depending on the time of collection of the fruiting bodies is important for determining a relatively safe portion for consumption. Analysis of the available data shows that the chemically best specimens of A. muscaria occur at the beginning of the season, when the first sites appear [9]. It has been reported that spring and summer mushrooms contain up to 10 times more ibotenic acid and muscimol than autumn-fruiting mushrooms [5]. It is worth noting that the amounts of the Rb, Cs, Pb, Sb, Tl and Ba metals, toxic to humans, were also higher in younger than in mature fruiting bodies [15]. Data indicates that the earliest growing specimens allow for more intense visions, while autumn specimens cause more physical effects [9]. Proportions of the chemical composition are also influenced by physicochemical processes such as drying or cooking, and the processing of mushrooms is intended to minimize the risk of unwanted side effects. It is worth noting that muscarine is thermostable and is not devastated by cooking [16]. Fresh mushrooms are the most poisonous due to the high concentration of ibotenic acid. Fly agaric poisoning results in death in 2-5% of cases. Mortality depends on the amount of poison absorbed. It has been calculated that the lethal dose for an adult is equivalent to eating 15 fresh caps [1].

In addition to its dried and raw form, the fly agaric is also taken in the form of tinctures and extracts, and is sometimes used as an ingredient in dishes. A very common way to dose the mushroom is to use small, subpsychoactive doses of no more than 0.5 g. Such microdosing is intended to potentially provide health benefits without causing hallucinations or other intense psychedelic effects. Some people have historically removed the skin (cuticle) from the fly agaric before consumption, in order to eliminate the largest amount of psychoactive substances. Cooking the mushroom also removes most of the active water-soluble substances under high heat. For example, Mexicans ate the fruiting body of A. muscaria without the skin and poured out the water after cooking. In Italy, after cooking and pouring out the water, the mushroom is stored in brine before consumption. In North America, the mushroom is dried and then smoked after the red skin is removed [6]. In 2022, B. Masha published the book “Microdosing of Fly Agaric” in which she collected the experiences of over 3,000 participants who tested the method in a wide range of diseases [17]. Selected ones are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Use of Amanita muscaria and feelings of people taking it in selected diseases and addictions, along with the number of participants and the percentage of positive, neutral and negative feelings

[i] Notes: Own elaboration based on Masha [17].

Impact on human health

British psychiatrist Ben Sessa has written that despite its “deadly” appearance, the toxicity, as well as the psychedelic effects, of the fly agaric are not particularly impressive. It can certainly cause harm, but reported fatalities are very rare [3,17]. With careful and rational use of the fly agaric, the risk of severe poisoning is very low, as is shown by data collected over several decades. However, psychoactive effects of ingestion can be difficult to predict and can also cause a number of unpleasant consequences, especially in the digestive system and the nervous system [9]. Consumption of A. muscaria causes transient excitation and depression of the central nervous system. In mushroom poisoning, the onset of symptoms occurs within 0.5-2 hours after ingestion, and their duration is on average 5-24 hours [18]. The consequences of taking the fly agaric are always directly dependent on the dose taken, the way the mushroom is processed, the health of the person, and even the place where the fruiting bodies are collected. The overall assessment of the advisability of using the species in a medical context also requires a multifactorial approach. In the context of the interaction of bioactive components contained in A. muscaria with human physiology on many levels, there are many ambiguities that require further research. What is more, the results of experiments to date are often inconclusive. For example, current medical research focuses on the potential use of muscimol as a GABAA receptor agonist in the treatment of tardive dyskinesia and Parkinson’s disease [11]. The diseases are associated with dopamine deficiency, and muscimol stimulates the synthesis of the neurotransmitter in nerve cells. It is worth noting, however, that elevated dopamine levels can cause a wide range of problems, from mental to physical disorders, hence the use of the property requires great caution and conducting clinical trials, and there is a huge risk if patients self-medicate with A. muscaria inspired by the type of research.

It has also been experimentally proven that the fly agaric extract causes changes in the morphology and localization of Iba1 in HMC3 cells (a model of human microglia), and also stimulates the cells to produce the chemokine IL-8. [19]. At the same time, no significant effect on the production of IL-6 was observed [20]. Such a reaction of HMC3 cells indicates their immune response to the components of this extract. At the current stage of research, the consequences of the interaction are not fully understood. The existing results suggest that A. muscaria components may have both therapeutic potential (e.g. neuroprotective effects – hypothetically, IL-8 may play a role in tissue repair) and pathological potential (it may potentially exacerbate inflammatory processes in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s).

Opportunities for therapeutic use

Studying the psychoactive alkaloids contained in A. muscaria, as interacting with GABA receptors in humans, could potentially lead to the treatment of anxiety, cognitive disorders, addictions, and insomnia [6], as well as contribute to the development of methods supporting the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. The speculations are related, among others, to the ability of psychedelics to stimulate the formation of new connections between nerve cells, thereby inducing neuronal plasticity [21]. A study published in 2021 observed that fruit flies fed different doses of muscimol (from 1 mM to 5 mM) were significantly less mobile, as compared to the control group. The highest amount of muscimol caused a complete loss of movement and a phenotype resembling catalepsy. Muscimol, as a strong agonist of the GABAA receptor, has the ability to inhibit the activity of the central nervous system, suggesting its potential use in relieving anxiety and improving sleep quality [22]. It has also been shown that infusion of low doses of muscimol into different brain regions, such as the ventral hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and amygdala, involved in emotional processes, disrupted conditioned fear memory in rats. The finding also underlines the importance of conducting research on the potential use of muscimol in the treatment of emotional disorders, including anxiety. The fly agaric extract with a high concentration of muscimol also showed an interesting neuroprotective effect on the synaptosomes of the brain of rats exposed to the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine, significantly increasing their viability, as compared to control samples, in which the toxin caused the formation of reactive oxygen species and quinones in cells, a process characteristic of Parkinson’s disease [1].

In another study, which also documented the ability of the extract to protect neurons in an in vitro model, it was also shown that it does not affect the activity of the enzyme monoamine oxidase-B (hMAOB), being involved in the breakdown of neurotransmitters in the brain [23]. In rats, it was also noted that the administration of 0.1 mg/kg muscimol protected the hippocampus from apoptosis [24]. Components of the fly agaric are also being studied for their antioxidant properties [25] and as potential agents in cancer therapy. Muscimol has shown interesting effects in attenuating the progression of gastric carcinogenesis in rats [12], and the acetone extract of A. muscaria induced proapoptotic effects in JAR cells while exhibiting antiferroptotic activity, suggesting its potential as an innovative therapeutic agent in the treatment of choriocarcinoma. Proapoptotic and antiferroptotic effects may be valuable complements to the existing therapies, especially in tumors resistant to programmed cell death [26]. What is more, current evidence indicates that muscimol improves plasticity in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, which serves as a central termination point of afferent pain pathways and is affected by both central and peripheral nerve injuries. Muscimol’s rapid onset and GABAergic properties make it a promising agent for pain management. Its ability to selectively bind to specific GABAA receptor subtypes may also open up the possibility of developing more targeted pain therapies with fewer side effects [27].

Health hazards

Increased consumer interest and widespread availability of products containing A. muscaria have raised public health concerns because they contain toxic compounds such as muscimol, ibotenic acid, and muscarine. Most of the scientific literature on the effects of A. muscaria on human health refers to studies involving the consumption of raw mushrooms of the species, with reported effects including dizziness, dysphoria, visual hallucinations, agitation, ataxia, muscle fasciculations, seizures, and coma. Even though deaths are rare, they have been reported [11].

Consumers are increasingly turning to the mushrooms as potential anti-anxiety and antidepressant agents, despite the lack of sufficient clinical evidence for their efficacy. It may lead to prolongation of symptoms that could otherwise be effectively alleviated by proven therapies [7]. The effects of A. muscaria on brain tissue and cells remain unknown [20]. As previously described, the alkaloids found in the fly agaric mushroom can indeed have a wide range of applications in supporting therapies of various diseases and in the production of pharmaceuticals, but one cannot ignore the fact that the components exhibit psychedelic properties. Due to the potential risk of abuse and addiction associated with therapy based on such substances, it is important to conduct further research on their safety and therapeutic use, it is important to study their analogues and produce derivatives of the active compounds that retain the same therapeutic properties but do not have psychoactive effects [6]. Estimates suggest that the toxicity of both muscimol and ibotenic acid in oral mouse models is higher (lower LD50) than for most commonly used psychotropic drugs, including fentanyl, cocaine, and phencyclidine (commonly known as PCP). LD50 for muscimol: 22 mg/kg, for ibotenic acid 38 mg/kg, for fentanyl: 368 mg/kg, for cocaine: 99 mg/kg, for phencyclidine (PCP): 75 mg/kg [7].

In the context of the risks associated with the use of the mushroom, it is also worth noting that A. muscaria commonly grows in places contaminated with metals and has a significant capacity to accumulate them. For example, fruit bodies from a chemically contaminated area near a lead smelter near Příbram in the central Czech Republic were characterized by elevated concentrations of cadmium (Cd) and zinc (Zn) [28]. The species also efficiently accumulates other heavy metals, such as mercury (Hg), rubidium (Rb), and vanadium (V) [1], with the caps usually containing higher concentrations of metallic elements and metalloids than the stems. The forms of Hg found in the fly agaric have been shown to be cytotoxic to animal nerve cells, with methylated forms showing significantly greater toxicity [29].

In light of the information, the medical/clinical use of the fly agaric should necessarily be preceded by further thorough research and considerable caution, while its amateur use, due to its toxicity and psychoactive properties, poses a direct health hazard.

Administrative regulations regarding the use of fly agaric mushrooms

Unlike other psychoactive mushrooms, the consumption and trade of the fly agaric is often not regulated by law, making it easily available for purchase online through social media in groups interested in the issue. The introduction of an increasing number of regulations related to drug policy has unfortunately contributed to the increased search for legal and easily accessible new psychoactive substances [18]. For example, collecting and possessing the mushroom is legal in many countries, including the United States, where it is not subject to any legal regulations in all states except Louisiana, which banned its use in 2005 [4]. Products containing fly agaric mushrooms and advertised as a homeopathic remedy for many diseases can be purchased on one of the largest e-commerce platforms in Poland. It is enough to enter the phrase “Amanita muscaria” and you will easily find more than 100 such offers [2]. There are no age restrictions for purchasing such products, and the product descriptions do not include information on safe dosage or contraindications [7]. Administering such products to children is particularly risky, as there are studies documenting that ibotenic acid causes extensive damage to neurons in the immature nervous system [30]. Currently, the trade in the fly agaric is not subject to any regulations in Polish law, and the active substances contained in the mushroom, such as muscimol or ibotenic acid, are not on the list of controlled substances under the Act on Counteracting Drug Addiction, so despite its psychoactive properties, possession, collection or consumption is not directly prohibited by law in Poland [31]. It is also worth noting that the A. muscaria is not included in the Food and Nutrition Safety Act or the Regulation issued thereunder specifying the species of mushrooms permitted for trade or production of mushroom products [32,33].

Conclusions

The fly agaric has psychoactive properties and is toxic to the human body, and its consumption in large quantities can be fatal. The effects of taking the fly agaric depend on the dose taken, the way the mushroom is processed, the health of the person, and even the place where the fruiting bodies are collected. Despite its general harmfulness, it shows potential for beneficial effects, such as protecting nervous system cells, modulating inflammatory processes, or reducing oxidative stress, which is why it can be used in the production of new drugs. The metabolic profile of A. muscaria, including the alkaloids with the highest biological activity (muscimol, ibotenic acid, muscarine), remains surprisingly poorly understood, which, given the growing popularity of amateur use of the mushroom, poses a serious risk to public health. For hundreds of years, the fly agaric has been used in many cultures, mainly during religious rituals and in folk medicine. In today’s society, the desire to use A. Muscaria is associated with a great interest in the subject of natural therapies, but the mushroom is also used for its hallucinogenic effects. Detailed studies on the toxicity of the fly agaric are urgently needed to increase public awareness of the risks associated with its use.