Introduction

Laparoscopy is established as the treatment of choice for symptomatic appendicitis, cholelithiasis, and benign gynecologic disease. The lack of depth perception and spatial orientation are drawbacks of conventional two-dimensional (2D) laparoscopic surgery. In the past few decades, three-dimensional (3D) imaging systems have been introduced in an attempt to improve depth perception and spatial orientation during laparoscopic interventions.

However, 3D imaging has not been widely adopted in laparoscopy because of its higher cost compared to 2D imaging and due to the rapid growth of robotic daVinci laparoscopy [1, 2]. In addition, 3D imaging often leads to headache and eye fatigue, so-called “visually induced motion sickness” (VIMS) [3, 4]. However, there has been no previous study that focused on the side effects of 3D laparoscopy such as VIMS, particularly during the initial experience.

Aim

We aimed to evaluate the incidence and severity of VIMS during 3D laparoscopy in operators without prior experience. We also evaluated personal preference, discomfort, and the mental and physical demands of 3D laparoscopy.

Material and methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea. One attending surgeon and 8 assistant surgeons who had never experienced 3D laparoscopy were recruited as participants for this study between December 2017 and August 2018. Each participant performed 10 consecutive cases of 3D laparoscopy in patients with benign or premalignant gynecologic diseases after the approval of the Institutional Review Board. All data were collected prospectively (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02405936).

Study treatment

General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation was achieved, patients were placed in the deep Trendelenburg position. The laparoscopic port (or trocar) placement was determined according to a patient’s need or according to the surgeon’s decision. After a pneumoperitoneum was created following insufflation with carbon dioxide, a laparoscope was inserted through the umbilical port. For the 3D imaging system, either a 10-mm ENDOEYE FLEX 3D Deflectable Videoscope LTF-190-10-3D (Olympus Corp., Hamburg, Germany) or a 10-mm ENDOEYE 30˚ rigid 3D Videoscope WA50082A (Olympus Corp.), was used. The master monitor was adjusted by a circulating nurse to fit the attending surgeon’s height and view. The 3D image was also displayed for two assistants on the slave monitor (Figure 1).

The intended surgical procedures such as ovarian cystectomy, myomectomy, and hysterectomy were then performed. After the laparoscopic procedure was completed, the transumbilical fascia and the skin were closed with 1-0 Vicryl suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) and 4-0 Stratafix suture (Ethicon), respectively. Patients were discharged from hospital after restoration of bowel activity, successful ambulation, the absence of postoperative fever, and when they no longer needed narcotic analgesics. All patients were scheduled for follow-up examinations at 1 week and 3 months after surgery.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the incidence and severity of VIMS. The score of VIMS was evaluated using the validated Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ), introduced by Kennedy et al. [5] and used in many studies on 3D movies, 3D glasses, and 3D virtual reality games [6–8]. The questionnaire consists of 16 items on a four-point scale from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), with higher scores indicating worse motion sickness. According to the interpretation by Kennedy et al. [9], “less than 5 points”, “5–10 points”, and “more than 10 points” were regarded as “negligible VIMS”, “mild VIMS”, and “severe VIMS”, respectively. To evaluate the incidence and severity of VIMS over time, each trial of 3D laparoscopy was arranged in consecutive order, based on the date of surgery.

The secondary outcome measures were the physical demand and the mental demand during 3D laparoscopy, which were adopted from the NASA task load index [10]. Immediately after each operation, all participants completed the specially designed questionnaire on 3D laparoscopy including a question on physical demand, “how physically demanding was the surgery?”, and a question on mental demand, “how mentally demanding was the surgery?”, both scored on a scale from 0 (very low) to 10 (very high). The in-depth perception, the comfort during surgery, safety of the 3D system, and preferences and the discomfort related to 3D laparoscopy were also evaluated, using SSQ. In-depth perception was assessed using a 10-point scale, in which a higher score indicated deeper perception. Comfort during surgery was assessed using the statement “I felt the 3D imaging system was comfortable for me,” and scored on a scale of 0 (very uncomfortable) to 10 (very comfortable). Safety of the 3D system was assessed using the statement “I felt the 3D imaging system was safe for the surgery,” and scored on a scale of 0 (very unsafe) to 10 (very safe).

Statistical analysis

The software SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. For continuous variables, data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range (IQR)), after verifying that the data were normally distributed. For categorical variables, data were presented as frequencies (percentages).

Results

This prospective observational study was carried out for 9 months, starting from our first case of 3D laparoscopy in December 2017. The baseline characteristics of the 9 study participants comprising one attending surgeon and 8 assistant surgeons, who performed 3D laparoscopy, are shown in Table I. The mean age and body mass index of the participants were 32.4 ±4.0 years and 20.8 ±3.5 kg/m2, respectively. None of the participants had a history of neurologic vestibular disorder. Each participant had performed 10 cases of 3D laparoscopy.

Table I

Baseline characteristics of surgeons (n = 9)

Table II shows the clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of the 45 patients with gynecologic diseases who underwent 3D laparoscopy during the study period. 3D laparoscopy was performed by single-port access in 40 (88.9%) cases, and multi-port access in 5 (11.1%) cases. Among the surgical cases, 29 (64.4%) were ovarian surgery, 15 (33.3%) were hysterectomy, and 1 (2.2%) case was myomectomy. The mean operative time, and median hospital stay were 77.8 ±35.8 min and 2 (2, 2) days, respectively. One case of postoperative ovarian bleeding that occurred 2 days after ovarian cystectomy was managed by controlling the bleeding laparoscopically.

Table II

Clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of patients (n = 45)

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age [year] | 38.6 ±11.7 |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 22.7 ±3.9 |

| Abdominal surgery history | 13 (28.9%) |

| Comorbiditya | 4 (8.9%) |

| Preoperative CA125 [IU/ml] | 28.6 (14.3, 50.4) |

| Operating time: | |

| Morning (8 AM – MD) | 32 (71.1%) |

| Afternoon (MD – 5 PM) | 13 (28.9%) |

| Laparoscopic approach: | |

| Single-port laparoscopy | 40 (88.9%) |

| Multi-port laparoscopy | 5 (11.1%) |

| Procedure performed: | |

| Ovarian surgery | 29 (64.4%) |

| Myomectomy | 1 (2.2%) |

| Hysterectomy | 15 (33.3%) |

| Adhesiolysis | 16 (35.6%) |

| Operative time [min] | 77.8 ±35.8 |

| Operative blood loss [ml] | 35.0 ±25.0 |

| Serum hemoglobin change [g/dl] | 1.9 ±1.3 |

| Transfusion | 2 (4.4%) |

| Pathology: | |

| Benign | 43 (95.6%) |

| Premalignantb | 2 (4.4%) |

| Failure of intended surgery: | 3 (6.7%) |

| Additional port insertion | 3 (6.7%) |

| Conversion to open surgery | 0 |

| Postoperative hospital stays [days] | 2 (2, 2) |

| Intraoperative complication | 0 |

| Postoperative complicationc | 1 |

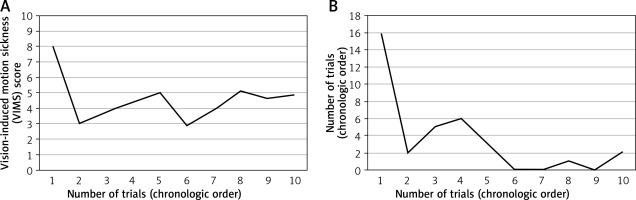

The incidence and severity of VIMS over time are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3. During their first case of 3D laparoscopy, 67% of the participants experienced VIMS. The symptoms were mild and severe in 22% and 44%, respectively. The incidence of VIMS dramatically decreased from the second case onward, but it had not completely disappeared and was maintained in 22–44% of participants until the last, tenth case (Figure 2). Moreover, a few participants (11–22%) still complained of severe motion sickness despite several sessions of 3D laparoscopy. The VIMS score indicative of the severity of symptoms was markedly decreased after the first case in all participants. This tendency was more apparent in the attending surgeon (Figure 3). The mean score of VIMS from the first to the tenth case for all participants (n = 9), and one attending surgeon, were 4.6 ±1.4 and 3.5 ±4.9, respectively (Table III). The physical and mental demand of 3D laparoscopy were 3.1 ±1.1 and 2.8 ±1.1, respectively, suggesting that the 3D laparoscopic surgery was bearable and did not overburden the participants. The scores of in-depth perception, comfort during the surgery, and safety on the 3D system were 8.0 ±1.5, 6.5 ±1.3, and 6.8 ±1.5, respectively, suggesting that 3D laparoscopy gives surgeons better in-depth perception, comfort, and safety than 2D laparoscopy.

Table III

Primary and secondary outcomes

Figure 3

Severity of vision-induced motion sickness over time: A – all participants (n = 9), B – one attending surgeon. Visually induced motion sickness was assessed using the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ), in which higher score indicates worse sickness

Figure 4 shows the personal preferences, discomfort, and ease of 3D laparoscopy. Among the 84 responses of the specially designed questionnaire by which participants were assessed after each operation, 61 (72.6%) were “favor 3D laparoscopy”, and 47 (55.9%) were “no” with respect to the discomfort using 3D laparoscopy. Most participants felt that 3D laparoscopy was easier than 2D laparoscopy.

Discussion

We conducted this study to evaluate the incidence and severity of VIMS during 3D laparoscopy in operators without prior experience. The main finding of this study was that 67% of surgeons experienced VIMS at their first case of 3D laparoscopy. We also found that the incidence and severity of VIMS were dramatically decreased from the second case onward. However, VIMS had not completely disappeared, and was maintained in some surgeons (22–44%), until the tenth case. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate 3D laparoscopy-related side effects in surgeons during their initial experience. We believe that the findings of this study will be valuable to laparoscopists who have never experienced 3D laparoscopy.

The present study showed that 3D laparoscopy causes various kinds of discomfort in surgeons, such as headache, dizziness, and eye strain due to blurring of vision, during their initial experience. Previous research on professional exposures to stereoscopic displays [11, 12], vehicle simulators [13], and virtual reality games [14], have also reported several adverse health effects induced by viewing motion images, including visual fatigue [11], and VIMS [13]. Hanna et al. [15] and Tung et al. [16] reported on the discomfort experienced by surgeons during 3D laparoscopy for cholecystectomy (increased visual strain, headache, facial discomfort, ear discomfort, physical discomfort, and dizziness), as compared to that of 2D laparoscopy. In conjunction, evidence from the present and previous studies suggests that the rates of occurrence of visually induced symptoms are high. This indicates the need for raising surgeons’ awareness of the possible discomfort that susceptible individuals may suffer during 3D laparoscopy, particularly during their first case.

In this study, the symptoms of VIMS were worse in the 8 assistants compared to those in the one attending surgeon (4.7 ±4.5 vs. 3.5 ±2.5). Surprisingly, severe symptoms of nausea and vomiting were noted after the surgery in a scrub nurse who had initially experienced 3D laparoscopy. Moreover, some scrub nurses hesitated to participate in the 3D laparoscopy sessions. This phenomenon could be explained by the “stereopsis comfort zone” defined by Mendiburu [17]. If the 3D display is too close, too far, or oblique, it causes uncomfortable retinal rivalry areas (Mendiburu even calls them “painful areas”). Therefore, Kunert et al. recommended the practical use of 3D images, such as handling the scope with care (shocks and bending of the shaft must be avoided), and fitting 3D display according to each surgeon’s height and view [1].

In most cases, immediately after surgery, the participants responded in favor of the 3D imaging system. When explaining their preference for 3D imaging, they considered the in-depth perception of the 3D system to be the key point. The participants also stated that they believed in the safety of the 3D system. This has also been shown in recent studies, by assessing with dry lab skill training (box trainer) [18, 19].

This study had some limitations. Firstly, only one surgical team performed all the procedures. Therefore, our results may not be reproducible when the operation is performed in other surgical environments, or with other 3D imaging systems. Secondly, we did not perform a sample size calculation, and analyzed the data based on the participants’ experiences in only 10 cases. However, we believe that 10 cases were sufficient to evaluate the incidence and severity of VIMS during 3D laparoscopy in operators with no prior experience, because the incidence and severity of VIMS stabilized from the second case onward. Thirdly, the incidence and severity of VIMS could vary with the age, gender, and ethnicity, similar to the case of riding a roller coaster [20, 21]. The age of participants was clustered in the late twenties to the early thirties in this study. This might have led to underestimating the incidence of VIMS induced by 3D laparoscopy. Finally, our findings may not be generalized because VIMS itself is primarily dependant on the surgeon’s condition on that day, and on the level of surgical difficulty.

Conclusions

The incidence of VIMS was 67% during the first case of 3D laparoscopy, but was dramatically decreased in 22–44% from the second case onward. Therefore, some laparoscopists without prior experience of 3D laparoscopy may develop a “3D vision syndrome”, as noted by Maino [22], because 3D viewing increases task burdens for the visual system during the initial experience. However, further large prospective trials are needed from various surgical settings, to obtain more conclusive data.