INTRODUCTION

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is one of the most recognizable, life-threatening eating disorders, commonly beginning during adolescence and early adulthood [1, 2]. The median onset age for is approximately 12 [3], with a remarkable increase in incidence among girls aged 10-14 [4, 5]. The lifetime prevalence of AN is three times higher for females (0.9%) than it is for males (0.3%). It also co-occurs with other mental disorders, among which the most frequent are anxiety disorders, as observed in 47.9% of patients [3].

AN is characterized by a tendency for self-starvation and preoccupation with weight [5]. Patients diagnosed with AN are absorbed with dietary restrictions aimed at reducing their weight and keeping them thin. They report experiencing an intense fear of becoming fat, which usually corresponds with certain behaviors aimed at maintaining a low body weight. AN is also accompanied by disturbed self-evaluation and body image as well as a persistent lack of recognition of actual body weight and the seriousness of the health conditions it corresponds with [6]. Apart from the symptoms included in the diagnostic criteria for AN – i.e. significant reduction of food intake accompanied by extremely low body weight, a persistent tendency to remain thin, distortion of body image, excessive fear of gaining weight, and disturbed eating behaviors [7, 8] – researchers studying teenage patients suffering from AN aim to identify the specific factors connected with AN in the developmental stage of adolescence. Based on the research conducted to date, genetic and biological as well as psychological, socio-cultural, and family factors have been identified [8].

The number of people affected by AN is gradually increasing, while at the same time mental health professionals working with eating disorders emphasize that there is also evidence of a great denial of a problem among patients suffering from this disorder. Therefore it might be hypothesized that the epidemiological data on AN is highly underestimated. It is believed by researchers that some people who suffer with symptoms of AN and need professional help do not look for any kind ofsupport [9]. In Poland it is estimated that the problem of AN concerns approximately 0.8%-1.8% of females under 18 years of age [10], but so far no nationwide analyses of the prevalence of eating disorders have been conducted. The latest international, as well as Polish, analyses prove that AN is becoming an increasing problem, especially among people under 15 years of age [9, 11]. According to the Office on Women’s Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [12], AN appears on average at 16 or 17, while the highest risk for this disorder appears between 13 and 19 and in the early 20s. In other studies it was estimated that the mean age of onset is approximately at 14-15 [4, 9], but the most recent studies have underlined the fact that the incidence of AN among people under 15 is gradually increasing [9, 11]. Based on the data published so far it is difficult to assess the percentage of cases of AN with an age of onset between 12 and 14 or younger, but there are a growing amount of papers describing patients first diagnosed at 8 [e.g. 2, 4, 13] or even younger [e.g. 14, 15]. The highest rates of AN symptoms are observed in females aged 12-25 [9, 11]. Even though the problem is present in both females and males it is, as already noted, more frequent for women, with an approximate lifetime prevalence ratio of 10:1 in women compared to men [16].

It is stated in the literature that the development of effective treatment methods is crucial,especially given the high mortality rate among sufferers of AN [9, 17, 18]. It is estimated that approximately 5% to 10% of all patients suffering AN die due to reasons accompanying the eating disorder [9]. Approximately 50% of all deaths observed in AN patients are caused by complications resulting from starvation [19], while about 6% of all patients suffering AN commit suicide [9]. Research shows that among the therapeutic approaches most often offered in adult populations of AN patients there are the following: cognitive-behavioral therapy, exposure and response prevention, acceptance and commitment therapy, and supportive therapy [20]. It is also suggested in empirical studies that with complicated cases not responding to the above-mentioned treatments, Schema Therapy may be effective [21, 22]. However, according to the recommendations of NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, in the UK), the most effective treatment methods for application in the adult population of AN patients are individual eating disorder-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, the Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults, and specialist supportive clinical management [23]. In the adolescent population of patients with AN it is recommended to offera family-based treatment in the first place [20, 23]. If for some justifiable reasons family-based therapy is not applicable it is recommended to apply either individual eating disorder-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy or adolescent-focused psychotherapy for AN [23].

The currently offered treatment methods for AN patients are clinically effective in approximately 50% of cases [24]. Additionally, at least one relapse (typically occurring within the first year of leaving the treatment program) is observed in over 50% ofcases [25]. Therefore new methods of treatment for AN patients should be investigated. According to the data published so far none of the current approaches is significantly better than the others, and there is a relatively large group of patients who do not respond well to any given therapeutic methods [20, 24]. One of the promising approaches that should be taken into consideration while looking for effective treatment methods is Schema Therapy.

Schema Therapy can serve as a transdiagnostic approach that is especially useful for the treatment of complex eating disorders that have been unresponsive to other treatment methods [26]. It is an integrative approach, connecting different therapeutic models in order to assist inrecognizing and addressing the specific and most crucial emotional problems developed during the early years of an individual patient’s life [27]. The following sections include the basic information concerning factors linked to AN, including both internal, biological, and external, environmental components. Following this, recommended treatment methods for adolescents with AN will be presented with attention given to the efficaciousness of those methods. An overview of a functional model of AN in adolescents will be introduced in the section after that, followed by data on Schema Therapy – understood as an alternative treatment methodfor teenagers. Information concerning dysfunctional beliefs and maladaptive schemas, as well as the modes observed in eating disorders, will be given in subsequent sections. A schema treatment model for adolescents with AN will then be introduced, and followed by data on possible applications of this treatment method in this group of patients.

FACTORS LINKED TO ANOREXIA NERVOSA

It is believed that development of AN is a result of complex interactions between genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors [28], but it is also worth emphasizing that the symptoms of this disorder observed in teenagers can go unnoticed or be misinterpreted as evidence of teenage rebellion, connected to depressive disorder, or a behavior aiming at attracting the attention of others [29]. It is therefore important to pay special attention to both internal (i.e. genetic, temperamental, and developmental) and external (i.e. childhood environment, parental relationships, and peer relationships) factors connected to the development of AN.

It is believed that genetic factors are responsible for 40% to 60% of the susceptibility of an individual to eating disorders [30], while the estimated contribution of genes to the risk of the development of AN reaches 50% to 74% [31]. It has been reported in the literature that patients suffering with AN share some genetic abnormalities related to metabolism, especially to production of cholesterol, fasting insulin and glucose, and a tendency towards obesity [30]. Also, some abnormalities in genes involved in regulating appetite, anxiety, and depression were discovered in patients diagnosed with AN [32]. There are reports demonstrating that people born into a family in which someone has suffered AN are 11 times more likely than others to develop such conditions themselves [30, 33]. In other studies it has been shown that the susceptibility to AN is four times higher among family members [34]. A higher likelihood of the development of AN was observed in monozygotic twins in comparison to dizygotic twins [35]. It is therefore believed that AN has a strong genetic component [36, 37], especially in cases of clinically diagnosed patients in comparison to the persons with subclinical symptoms of this disorder [38].

In patients with AN there have also been observed malfunctions within the biological systems connected with serotonergic and dopamine pathways as well as in appetite-regulating hormones [36]. It is hypothesized that there are abnormalities in the serotonin gene of patients with AN [39]. The low levels of dopamine metabolite observed in this group of patients may cause changes in their behaviors, increase the tendency to diet and self- starvation [40], or lead to behavioral inhibition [31]. In other words, AN is a very complicated disorder with predisposing factors including personal traits, connected with endocrine or neurotransmitter malfunctions [36].

There are also studies describing the relationships between temperamental and personality traits and the development and maintenance of AN [41, 42]. Among the specific factors observed in patients with AN are harm avoidance, negative emotionality, rigidity, and perfectionism [43-48], as well as a tendency towards anxiety and depression understood as temperamental traits [46]. It has also been stated that eating disorders, including AN, correspond with elevated levels of neuroticism, avoidance motivation, and heightened sensitivity to social rewards [45]. In a group of teenage patients suffering with AN a high level of impulsivity was also observed [49, 50].

Among the important psychological factors associated with AN in adolescence, environmental pressure leading to body dissatisfaction has been mentioned [51]. It has also been underlined that teenage girls experience a high degree of instability of self-image and low self-esteem [8, 52], which leads consequently to a negative general attitude toward themselves [8]. Socio-cultural factors corresponding with AN include internalization of the thin ideal, media influence and weight-related bullying [8].

When analyzing family factors disturbed communication, authoritarian parenting styles and general family functioning, including the modeling of disturbed attitudes toward eating, are mentioned [8, 28]. There are also results proving that overprotective as well as nonresponsive parents may contribute to the development of AN [53]. Among other family-related factors increasing the risk of this, specific patterns of relationships between family members [54], along with socio-economic components [55], are also mentioned.

The most significant factors connected with AN are usually described and interpreted as those pertaining to risk and maintenance [53]. It is important to emphasize that some of the components connected with AN are difficult to interpret as predisposing factors or consequences of AN since they can serve either role. It is therefore troublesome to clearly describe those components and the relationships between them. Among such factors there should be mentioned: excitement, a sense of power and control, a feeling of superiority, and elevated self-esteem,which are usually perceived as predisposing factors [55]. According to the literature those factors contribute to dietary behaviors and at the same time lead to a preoccupation with the reduction of food intake. As a result those factors intensify the disregard of body signals, obsessions and compulsions incorporated into a fixation on food, and perfectionism, which may be interpreted either as a risk or sustaining factor or as a consequence of AN. Similar to this is the status of the most debilitating factors connected with AN, i.e. emotional and mood disorders, including depression, anxiety, mood swings, fear of gaining weight, and distorted body image [55].

CURRENT RECOMMENDED TREATMENT METHODS FOR ADOLESCENTS WITH ANOREXIA NERVOSA

As stated above, according to the NICE recommendations for approaches to be used specifically with adolescent patients with AN, family-based treatment should be treated as a first choice intervention [20, 23]. In justified situations in which conducting family-based therapy is not possible, a teenage patient with AN should be offered either individual eating disorder-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy or adolescent-focused psychotherapy for AN [23]. Based on current empirical studies [57, 58] it can be stated that family-based therapy is the most efficacious in the treatment of AN, but other methods based on cognitive treatment modalities are also acceptable.

The studies published to date prove that among the most efficacious evidence-based interventions aimed at the treatment of AN there is family-based intervention. Described as most likely to be efficacious are systemic family therapy, individual insight-oriented psychotherapy, individual adolescent-focused therapy and parent- focused therapy. Among the possibly efficacious methods are mentioned guided self-help, telephone assisted therapy, family-based treatment enhanced with cognitive remediation training, and family-based treatment enriched with art therapy. As experimental treatments for patients suffering AN there are mentioned individual cognitive behavioral therapy, individual cognitive remediation training, intensive parental coaching within family-based treatment, DBT skills groups, family-based treatment supplemented with DBT skills, and family-based treatment guided self-help applied during the time of waiting for professional treatment [57].

According to the data [58], it is currently the case in several different countries, including Australia and New Zealand, Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, the UK, and the USA, there are published evidence- based practice guidelines providing information on treatment methods for AN in the adolescent population. For teenage patients suffering with AN the most frequently recommended is family-based therapy, and family therapy focused on AN [23, 59-63]. It has been proved that at one year from the start of family-based therapy conducted in the community approximately 44-57% of adolescent patients achieve weight restoration [64, 65]. Almost half of young patients suffering with AN do not respond well to currently offered treatments, mostly due to their lower weight, higher levels of perfectionism, higher levels of criticism within the family, and high levels of emotionality [66]. Therefore further research, including analyses of the efficiency and effectiveness of other approaches to the treatment of AN in adolescent patients, are still needed [57, 58].

Data presented in the literature proves that fewer than 1 in 5 patients recover within one year, one third report recovery within 2 years and at least 25% of teenage patients still suffer from AN 2 years after the diagnosis [24]. The effectiveness of both family based treatment methods as well as individual therapy approaches are debatable [65, 68], especially when a high level of emotionality is present in the family system [65]. Poor communication within the family, an authoritarian parenting style, the incorrect modeling of behaviors and beliefs related to eating, and inappropriate emotion regulation within the family system may result in teenagers in the development of disturbed attitudes toward eating [8, 28]. In certain cases disturbed food related behaviors can become an emotion regulation strategy, a coping strategy, a method for attracting the attention of other people or a way for sustaining the homeostasis within the family system. Research data suggests that such behaviors correspond with early maladaptive schemas and modes, which are essential for the development of eating disorders [67]. Based on those arguments it seems justifiable to pay close attention to Schema Therapy, as it is perceived as a transdiagnostic method of treatment that can address malfunctions within schemas developed in the early years [27].

THE HYPOTHETICAL FUNCTIONAL MODEL OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA IN ADOLESCENTS

Given the abovementioned complexity of relationships between different factors observed in adolescent patients suffering from AN, it seems justified to propose a new, hypothetical model explaining this disorder from a functional perspective. It is important to emphasize that in the literature many functional models of AN have already been presented [e.g. 56, 70, 71]. Those approaches aim to present a general understanding of the antecedents, current problems with and consequences of AN in a mostly universal manner [72]. Usually they focus on symptoms associated with the risks and consequences of self-imposed dietary restrictions [e.g. 73], conceptualize problems from the perspective of dysfunctional cognitive beliefs [e.g. 65], interpret eating disorders from the perspective of the operant learning approach [e.g. 74], or analyze dietary behaviors in the light of positive and negative reinforcement [e.g. 71]. In the case of functional model of AN in adolescence it seems important to relate specifically to the factors corresponding with this developmental stage.

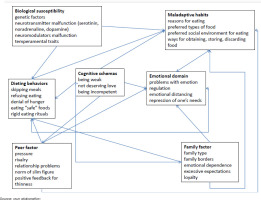

As was stated in the previous section, AN is related to various individual, biological, and environmental factors. Therefore to understand the functioning of a teenage person suffering from AN the maladaptive habits developed during learning processes should be taken into consideration, together with information concerning the dieting behaviors, cognitive schemas, and emotional functioning of an individual [71, 75]. Among the factors that should be attended to when analyzing anorexia nervosa there is also biological susceptibility. In addition, and especially in adolescents, factors connected to the family environment should be analyzed. It is believed that family system settings correspond with the development and maintenance of eating disorder symptoms, while in some cases observable disturbed relationships with eating present in one family member serve as a tool directed towards the sustaining of family homeostasis [76, 77].

Thus, when describing the factors involved in the development and maintenance of AN in teenagers it is important to analyze biological components, environmental factors (i.e. elements connected with family system and peer relationships), and personal components (i.e. cognitive, behavioral and emotional factors). Based on the data presented above it might be hypothesized that biological factors directly influence the formation and maintenance of dieting behaviors and maladaptive eating habits an individual presents. Genetic influences are probably especially strong in the preferences for certain types of food, refusal of food intake and, partly, in the denial of hunger. This assumption is based on the research that demonstrated that patients with AN have low levels of dopamine metabolite [78] and low levels of leptin [79]. It is also possible that all of the abovementioned factors play a crucial role in the maintenance of symptoms of AN. Family influences should be also considered as an important variable responsible for development of the maladaptive habits, dieting behaviors, cognitive schemas, and emotional regulation an individual forms throughout early years of life. Many of the studies conducted to date have confirmed the role of the family system, including modeling behaviors, creating an emotional environment responsible for emotion regulation and influencing the development of cognitive schemas in teenage patients suffering AN [80-87]. The development and maintenance of AN partly depends on peer environment as well. Behaviors presented by other young people influence dieting behaviors and may cause the maladaptive eating habits of an individual. Although this hypothesis is based on the previous results presented in the literature [88-90], it needs additional empirical verification.

The cognitive schemas developed by an individual suffering AN throughout their early life are probably among the most important factors responsible for the maintenance and relapses of an eating disorder. Also, it is possible that dysfunctional beliefs serve as a factor interfering with treatment effectiveness in standard therapies recommended by NICE [23]. This hypothesis needs empirical verification, since in the literature there is as yet no data on this topic. It is highly probable that maladaptive cognitive schemas lead to the maintenance of dieting behaviors and maladaptive eating habits perceived by an individual with AN as a strategy for coping with unwanted emotions as well as for sustaining relationships within the family and among peers. It is also possible that a disturbed relationship with eating serves as a compensating strategy for maladaptive cognitive schemas. Those hypotheses also require empirical verification. The complicated and diverse relationships between the factors involved in the development and maintenance of AN symptoms in adolescence, as described above, are presented in Figure I.

The complicated etiopathology of AN in teenagers as described above (see also [91]) can serve as an explanation of the reasons for the ineffectiveness of standard approaches to the treatment of AN in adolescence [24]. The main goal of the treatment is to improve the quality of life of a patient through the modification of their beliefs and behaviors, which is especially difficult in adolescents due to the developmental stage they are at. Many intrinsic and extrinsic changes take place during this period [92]. Teenagers are extremely sensitive to the cues connected with their own beliefs about themselves but, as was presented in the literature [93], the factors of concentration on eating, weight, and shape-related cognitions remain insufficient in explaining their disturbed relations with eating. It is also suggested that general, maladaptive schemas, not directly connected with eating disorders, are important aspects that should be taken into consideration when explaining the disturbed cognition of teenagers suffering with eating disorders [90, 95].

SCHEMA THERAPY AS AN ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT METHOD FOR ADOLESCENTS WITH ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Schema Therapy is a popular psychotherapeutic approach introduced especially for patients with diverse psychological problems that have not respond to other treatments [27, 96], or those dealing with complex difficulties, including long-term effects of trauma, abuse or emotional neglect [96]. This approach is intended to address rigid schema beliefs [27], based on the assumption that every individual experiences universal, core emotional needs that in some cases are not fulfilled. As a result of the neglect of early emotional needs,stable patterns of maladaptive ways of thinking, feeling, behaving, and coping with difficult situations are formed and established [27]. Those maladaptive, inflexible patterns of thinking and behaving are called early maladaptive schemas. They are formed during childhood and adolescence, and they include the full spectrum of body sensations, feelings, memories, and cognition.

The main concepts of Schema Therapy include Early Maladaptive Schemas, Schema Domains, Coping Styles, and Schema Modes. Early Maladaptive Schemas are described as persistent themes developed during childhood, and elaborated on throughout the life course, based on experiences regarding oneself and one’s relationships with others, especially within a hostile, critical, abusive, and neglectful environment [27]. Unsatisfied core needs, which are inadequate for the purpose of the child’s healthy development in their early environment, can be grouped into five domains: disconnection and rejection (formed as a result of experiences of abusive, unaffectionate or unstable family systems), impaired autonomy and performance (which is a result of excessive parental attention or no regard at all), impaired limits (which is a result of an overly liberal family environment), other directedness (effect of conditional love and acceptance from caretakers), and over-vigilance and inhibition (which are the result of a harsh parental approach) [97]. Coping Styles are used to describe the ways an individual adapts to the environment, and include three main strategies: overcompensation (behaving opposite to the schema), surrendering (acting according to the schema), and avoidance (avoiding schema activation). Schema Modes reflect the emotional and behavioral states experienced by an individual in certain situations [27].

It should be emphasized that among people suffering eating disorders indicators of low parental care, insecure attachment style, and high parental control have been identified [94, 99]; these are mediated by low self-efficacy, avoidant coping and early maladaptive schemas of defectiveness, abandonment, and vulnerability to harm [94]. According to the available data AN has a strong association with the avoidant attachment style [100]. Also, physical and emotional abuse have been proven to be predictors of eating disorders [101], while emotional abuse and invalidation have been proven as predictors of the severity of eating disorders [102]. Eating disorders co-occur with high levels of shame, rigid thinking patterns, perfectionism, and compulsive behaviors [94]. Due to the high degree of the complexity of the difficulties people suffering with eating disorders are faced with, compound treatment methods including biological, socio-psychological and developmental components are needed. Therefore, Schema Therapy seems a justified treatment method in this context. This therapeutic approach expands traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy by placing more emphasis on the therapeutic relationship, affect and mood states. It also accentuates the significance of lifelong coping styles together with their childhood origins as well as developmental processes resulting in the formation of maladaptive schemas and modes [103].

Based on the research conducted by Solmi and colleagues [104] it should be concluded that among the most important risk factors for the development of eating disorders there are early traumatic and stressful events that could be addressed throughout Schema Therapy. Research proves that Schema Therapy leads to a significant reduction of eating disorders and rumination in obesity [105]. It reduces the psychological distress, body image concerns, and dysfunctional beliefs recognized in eating disorders [106]. It also leads to a significant improvement in eating disorder severity, anxiety and shame levels [107]. In other words, there are a growing number of studies proving that Schema Therapy can serve as an effective treatment method for patients suffering severe and enduring forms of eating disorder[22, 107-110], even though further studies of this kind are still required.

DYSFUNCTIONAL BELIEFS AND MALADAPTIVE SCHEMAS OBSERVED IN EATING DISORDERS

The research demonstrates that people suffering with eating disorders present disorder-specific dysfunctional cognitive profiles including, among other things, excessive worry connected with an inability to control weight, ruminative thinking, and dysfunctional cognitive-affective processes [67, 111-113]. It is worth emphasizing that in first cognitive theories the main interest was directed toward individual, dysfunctional beliefs about weight and shape. It was stated that those beliefs are crucial in the maintenance of eating disorders [114]. Further empirical research revealed the presence of early maladaptive schemas that are not directly connected with eating, weight or food, but rather are the deep reflections of negative, unconditional beliefs about themselves that individuals present [103, 109, 116-119].

It was discovered that there is a correspondence between a low BMI and a high number of maladaptive core beliefs [119]. In patients with eating disorders there were found high levels of maladaptive schemas of emotional deprivation, mistrust/abuse, social isolation, defensiveness/shame, failure to achieve, functional dependence, vulnerability to harm, and subjugation [120, 121]. In other studies schemas of abandonment and vulnerability to harm were found in women with eating disorders [114-124]. Other researchers, on the other hand, discovered a high level of emotional inhibition schema in patients with eating disorders [125]. At the same time, researchers emphasized that – based on the results of these studies – it is only possible to differentiate between patients suffering eating disorders and non-clinical control groups, since there were no statistically significant differences between patients with different types of eating disorders [123]. In other studies the differentiation between bulimic and anorectic patients was made based on the abandonment and vulnerability to harm schemas that were higher in bulimic patients in comparison to the patients with anorexia [122]. There is also data showing a high level of abandonment and vulnerability to harm schemas in patients with bulimia nervosa [121]. In patients with AN schemas of unrelenting standards connected to a high level of perfectionism were discovered [126]. In addition, in studies conducted with non-clinical samples presenting a connection between disturbed relationships with eating, the connection between dysfunctional eating attitudes and schemas of defectiveness and dependence were described [127]. In general, it was stated that patients suffering eating disorders experience more dysfunctional beliefs in comparison to recovered patients and healthy controls [122].

The research shows, then, that most characteristic of patients with AN are schemas of abandonment, unrelenting standards, social isolation, failure, defectiveness and punitiveness [91], which are connected with the domains of disconnection and rejection and over-vigilance and inhibition. This means that persons with AN have most probably experienced relationships with unstable, unaffectionate or abusive caretakers. Patients are convinced that in order to earn attention and love from significant others they have to put a lot of effort into their actions. They also believe they won’t be able to achieve as much as others. Patients with AN also believe that in order to be accepted they have to hide their real self from other people, and they convinced that they are highly alienated from others they ‘do not fit’ in with [67, 109].

Analyses of relationships between maladaptive schemas and treatment outcomes in patients suffering eating disorders have revealed the strongest connection to be between the severity of symptoms of eating disorders and the schemas of impaired limits, impaired autonomy and performance, and over-vigilance and inhibition. Further to this, a connection between the length of the treatment and schemas of impaired limits and over-vigilance and inhibition has been demonstrated [128]. No change in the intensity of schemas of emotional deprivation, abandonment and self-sacrifice has been observed following recovery from eating disorders. Scores concerning schemas of mistrust and abuse, social isolation, defectiveness and shame, failure to achieve and vulnerability to harm decreased after the recovery from eating disorders, though at the same time they were still higher in comparison to the healthy control group. The intensity of schemas of dependence/incompetence, enmeshment, subjugation, emotional inhibition and unrelenting standards were statistically lower in recovered and control groups in comparison to patients with current eating disorders [122].

It has been discovered that levels of maladaptive core beliefs are higher in patients suffering eating disorders in comparison to the healthy control group [129]. It has been hypothesized that negative core beliefs, especially those concerning emotional deprivation, abandonment and self-sacrifice are inherently connected with a tendency to suffer from eating disorders [67, 122]. It has also been proved that early childhood environmental experiences, especially living in an invalidating and ‘chaotic’ family environment, contribute to the development of eating disorders [130]. Researchers have therefore suggested that the levels of maladaptive core beliefs may be understood as a risk factor for the development and relapse of eating disorders [122]. Given the high level of complexity of maladaptive schemas present in patients suffering eating disorders,and its relevance to the development, maintenance and treatment of eating disorders [128], it is justified to incorporate the assessment of maladaptive core beliefs and schemas and to apply Schema Therapy in this context.

DIFFERENT MODES IN EATING DISORDERS

Symptoms of eating disorders correspond with the maladaptive coping processes that help individuals to deal with difficulties connected with an anxious, perfectionistic, achievement-oriented personality [131], and high levels of sensitivity and empathy [132]. Those individual traits interact with the requirements and expectations of a childhood environment as well as the relationships an individual forms with significant others, and the family rules for eating-related behaviors [133]. Maladaptive, difficult or traumatic interactions with social environments (i.e. family or peers) can cause the development of insecure attachment, lack of autonomy or competence, or sense of identity. They can also be connected to problems with setting realistic limits and control, disturbed ability to be spontaneous and/ or lack of freedom in expressing emotions and individual needs [133, 134]. Additionally, patients suffering with AN are characterized by low tolerance for negative emotions, boredom and discomfort [67].

In order to cope with the problems described above, individuals suffering from eating disorders often employ maladaptive coping processes that are aimed at achieving an individually desired self-image [135] and emotion regulation [67]. According to Schema Therapy there are different modes used by individuals coping with difficulties; these modes are defined as coping mechanisms manifesting moment-to-moment [27]. There are child modes referring to innate vulnerability and presenting basic emotions. Coping modes are developed in order to cope with a mismatch between temperament and environmental expectations, serving as survival strategies of fight, flight or freeze. Inner critic modes represent internalized punitive, demanding, or guilt-inducing messages from the family and environment and unmet emotional needs. Healthy adult mode presents wisdom, kindness, and compassion of a good parent [27]. In the literature concerning eating disorders most often described are two child modes, two inner critic modes, and eight different coping modes [133]. Among the child modes there are: desperate for nurturance and protection, rejected and unattractive shamed/ deprived child, and passively-aggressively expressing suppressed anger, angry child. Inner critic modes include punitive critic and demanding critic that are responsible for unpleasant comments toward an individual. Coping modes include surrender modes with compliant surrender, dependent/ helpless surrender, and hopeless resigned, avoidant modes including detached protector and detached self-soother, and overcompensatory modes with superior overcompensator, Pollyanna overcompensator and over-controller modes [27, 133].

Among the most frequently observed child modes identified in AN there are the vulnerable child and angry child modes. Vulnerable child experiences anxiety, guilt, and sadness. Vulnerable child is lonely, dependent, and stressed. They feel rejected, hopeless, and powerless, and believe to be a burden to others. Due to those feelings, vulnerable child tend to meet others’ needs through achievements and physical appearance. Angry child experiences a lot of anger they suppress and direct toward themselves through self-punishment (e.g. starvation or excessive physical activity) [133]. The demanding and punishing inner critic modes lead to the formation of unrealistic standards regarding eating and the body shape and punishment through negative comments toward themselves. Usually in patients suffering AN the healthy adult mode is absent. An individual diagnosed with eating disorders does not show any compassion and understanding toward themselves and others, and is unable to remain balanced between pleasant activities and obligations [133]. Presence of maladaptive coping modes including detached protector and detached self-soother, leads to the detachment from any kind of bodily sensations, emotions and needs an individual experiences in different difficult or demanding situations. Such detachment sometimes leads to engagement in misuse of psychoactive substances, excessive exercises or vomiting that are used as a method for blocking any strong emotional states [133]. Overcompensatory superior overcompensator, and perfectionistic over-controller modes elicit a tendency to follow strict dietary rules or other regular behaviors (e.g. exercises) conducted on a daily basis in as perfect manner as it is possible [133]. Table 1 presents general descriptions of most frequent schema modes observed in AN.

Table 1

Most frequent coping modes observed in anorexia nervosa

Some research has found higher scores on schema modes in a group of patients with eating disorders in comparison to the non-clinical population [125, 137]. It was suggested that the modes of compliant surrender, detached self-soother and detached protector are more prevalent in people with eating disorders in comparison to other clinical groups [125]. Tendencies to overcompensation, avoidance, and surrender were found to be important factors in the maintenance of symptoms of eating disorders [138]. Schema modes in eating disorders were found to be relevant to primary avoidance of affect (i.e. involving individual attempts to avoid emotion activation) and secondary avoidance of affect (i.e. attempts to reduce the already activated affect) [139]. In other words, there are limited, empirically verified relationships between symptoms of eating disorders and schema modes that should be taken into account while working with patients suffering from disturbed relationships with eating [138, 140].

ANOREXIA NERVOSA IN ADOLESCENTS FROM THE SCHEMA THERAPY PERSPECTIVE

In the small number of studies conducted so far on relatively small samples Schema Therapy has been proved an effective treatment method for patients in this area [141, 142]. According to Jeffrey Young [27, 143], when an individual fails to satisfy their basic, core needs they develop, as a consequence, negative beliefs about themselves accompanied with negative emotions, which they tend to avoid [144]. A similar mechanism encompassing negative self-evaluation and unpleasant emotions is observed in families in which adolescent offspring suffer AN. It has been shown that whenever adult caregivers prevent their children from developing healthy autonomy, and separation the chances for the development of disturbed eating habits increase substantially [145-147]. It might therefore be hypothesized that the factors accountable for the development of maladaptive schemas are analogous to the circumstances leading to the development of AN [91].

It has been demonstrated that patients suffering from eating disorders exhibit severe early maladaptive schemas [148]. Individuals suffering AN believe that they are deficient, and do not deserve to be loved for who they are. Throughout the years they learn not to express their real feelings, as they’re convinced this would be an inappropriate behavior. AN patients also believe that satisfying other people is the only way to get their approval, and are also afraid that all people will abandon them. Based on those beliefs they take actions aimed at the adjustment of weight and body shape which, in the beginning, results in increased positive attention from others and higher social approval. In effect, they continue and aggravate their disturbed way of acting, especially in the face of their fear of possibly losing others’ interest. Individuals with AN believe that they are more prone than others to gain weight and are afraid that as soon as they desist from such controlled and harsh behaviors toward themselves they will lose everything. What is more, it has been found that persons suffering from eating disorders experience a low tolerance for unpleasant emotions, and discomfort [65]; therefore they also prefer to engage in avoidant coping modes that serve as strategies for dealing with difficulties [27].

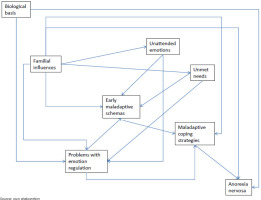

Based on the information stated above it might be hypothesized that, when analyzing the functioning of teenagers with AN, it is crucial to take into account the family system as well. Symptoms of eating disorders are connected with blurred boundaries between family members, stiff bonds within the family separating their members from the rest of society, a lack of emotional connectedness between members of the family, and/or internal conflicts within the family [149-151]. Core beliefs and unmet needs leading to the development of maladaptive schemas and coping modes are formed in disturbed family systems in which some form of abandonment or abuse is present [27, 133]. From a functional point of view, AN can serve an important role in maintaining family system homeostasis [80]. Symptoms of eating disorders can help to organize the behaviors of all family members in dysfunctional sequences that aim to maintain family connectedness and provide balance within a family system that has been destabilized or exposed to changes [152, 153]. The disturbed eating habits of a person with AN could also be developed due to some interactions with family members [154, 155]. It is important to underline the point that both eating disorders and maladaptive schemas develop in family systems on an emotionally disturbed basis. In Figure II the interactions between factors involved in the development and maintenance of AN from a Schema Therapy perspective are presented.

Figure II

Relationships between factors involved in development of anorexia nervosa symptoms according to schema therapy

As we see in the above, relationships between all the factors involved in the development of AN are very complicated. Biological components contribute mostly to the development of difficulties with emotional regulation and eating disorders. Temperamental sensitivity and impulsivity, along with the capacity to tolerate novel stimuli, change or uncertainty is highly correlated with emotional regulation [156, 157]. At the same time, additive genetic factors influence an individual’s susceptibility to AN [158, 159].

Family influences should be considered as one of the most important factors contributing to the development of AN. In dysfunctional families adolescents suffer from unmet needs, and do not receive adequate support in coping with difficult emotions which contribute to the development of early maladaptive schemas. In order to handle inadequate relationships within their family an individual may form maladaptive coping strategies. At the same time, the behaviors of carers or their expectations toward the child may cause the development of disturbed eating habits in young people [148].

It is worth emphasizing that the model described above and presented in Figure II is only hypothetical and needs empirical verification.

POTENTIAL APPLICATION OF SCHEMA THERAPY WITH ADOLESCENTS SUFFERING ANOREXIA NERVOSA

The relationships between all the factors contributing to the development of AN are very complicated, but it seems that those connected with the family system are especially crucial. Sources in the literature show that there are connections between AN and the avoidant attachment style [160]. It has also been found that there is a relationship between high levels of attachment anxiety and poorer treatment outcomes in patients [161]. In other studies, weak bonding between patients suffering eating disorders and their fathers were discovered; high degrees of overprotectiveness on the part of mothers of people with eating disorders have also been noted [94]; it has been shown that mothers of persons suffering from eating disorders were mostly abandoning and enmeshed in the relationship at the same time, while fathers were emotionally inhibited and neglectful [162]. Patients suffering eating disorders report high levels of traumatic experiences of different kinds [163, 164], which may be associated with more severe symptoms of eating disorders [165]. Based on their difficult experiences within family systems, such individuals, more often than persons without a diagnosis, develop most of the early maladaptive schema, most frequently that of unrelenting standards [166].Taking into consideration the extension of the problems observed in persons with eating disorders and the importance of factors connected to family settings, it seems justified to apply the Schema Therapy approach while working with adolescents suffering with AN, as ST has been among the approaches addressed to patients dealing with emotional neglect, abuse and traumatic experiences [96].

The full understanding and integration of the complex factors influencing development and maintenance of AN in teenagers is possible with a comprehensive case conceptualization, which allows a transdiagnostic understanding of an eating disorder and any comorbid problems. The most important component of case conceptualization in ST is the recognition of early maladaptive schemas specific to an individual. The identification of early maladaptive schemas should be accomplished on the basis of the information gathered on the previous experiences and current situation of an individual. This first phase of assessment usually takes approximately two to six sessions, depending on the degree to which an individual is able to present a coherent description of their current life and previous experiences [133]. During that time elementary data on the family history of mental disorders, family type and structure along with information concerning the main family rules and schemas are gathered.

Among the important factors investigated during the first phase of Schema Therapy are the relationships an individual suffering from AN has with both of their parents.Special attention should be given to potential triggers of maladaptive schemas (e.g. unmet needs, rejected emotions). Crucial for the development of early maladaptive schemas are the rules connected to discipline, possible indicators of physical, sexual or emotional abuse, potential losses of significant others, expectations towards an individual, the potential for parentification to occur, rules for expressing unpleasant emotions within a family, social connectedness in the family system, and potential supportive relationships with other people. In the case of AN it is also important to gather information about family rules connected to weight and eating, along with information on the past history of parents’ dieting, avoidant coping, obsessive rituals, purging etc. Data concerning parental viewpoints on self-control and will-power are also crucial. Since an eating disorder observed in one relative may be the sustaining factor for the integrity of the family it is also important to collect information about any secondary functions or the general role AN might have played so far in the family system (e.g. drawing attention away from other problems, securing connections between family members) [133].

While establishing a conceptual understanding of patients with AN it is important to include data on the current situation and status of an individual, so that the comprehensive assessment of symptoms is indisputable. Any comorbid conditions should be taken into consideration as well (e.g. depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance misuse). Information concerning current relationships with other people, and data on everyday functioning and activities are also very important. An investigation of any traits possibly linked with disturbed eating habits (e.g. compulsivity, perfectionism, emotional instability, a high need for control) is also needed in order to gather as comprehensive as possible an assessment of an individual suffering with AN. Body image and beliefs about the role the body plays in successful functioning are also important factors that should be assessed during this process of building up a conceptual understanding of the patient [133].

During therapeutic sessions, an individual learns to recognize their emotions, and tries to identify the early maladaptive schemas, schema modes, and maladaptive coping strategies that were present during the situation discussed over the course of a meeting. It seems that one of the most important factors responsible for the recovery of a patient suffering with AN is establishing the healthy adult mode, which presents an adequate view of oneself and others. It includes an objective and reasonable assessment of the emotions and processes observed in difficult and demanding situations [27]. In patients with AN this mode is usually introduced alongside the practicing of limited reparenting within therapeutic relationships. Limited reparenting provides corrective emotional experiences, helps in the validation of feelings an individual experiences, and improves their understanding of maladaptive schema origins. It involves reaching the vulnerable child mode and helps to set limits on the compensatory modes as well as combat demanding and punitive adult modes [27]. It might be hypothesized that limited reparenting is extremely important, especially for adolescents with AN experiencing difficulties within their family systems that are not responsive to family-based treatment, though no empirical studies on that matter have been published to date; there is only limited information emphasizing the importance of limited reparenting in the process of the correction of emotional experiences [167].

In Schema Therapy for adolescent patients with AN, modified versions of standard techniques (e.g. imagery rescripting, chairwork) are used. Imagery rescripting and chairwork in the treatment of AN are crucial for bypassing coping modes and accessing the vulnerable child mode in order to provide an adequate reparenting process. Imagery rescripting helps to counteract the assumptions associated with early maladaptive schemas. It includes the recollection of childhood memory linked to specific maladaptive schema, described from a child’s perspective (in the present tense, and in the first person). Next, the process of rescripting and setting limits to the antagonist (usually a parent rejecting a child’s core needs) done by a therapist, or the patient in healthy adult mode, is offered until the child is soothed. The last phase includes the repeated recollection of previously described memory, but with a corrected interaction with the adult who this time fulfills the emotional needs of the child [27].

Imagery rescripting helps to identify the factors involved in the development of eating disorders. The main aim of the chair work in the treatment of eating disorders is to clarify the roles of the coping modes. This method of work helps with the expression of abstract ideas of schemas and modes. It can be used to resolve distressing events experienced in childhood, as well as to overcome difficulties in emotion regulation or fulfilling an individual’s needs [27]. Besides the standard use of chairwork, in eating disorders it is also possible to use this techniquefor the identification and addressing of the ‘eating disorder voice’ that an individual suffering with AN can recognize. Imagery rescripting and chairwork seem important since they operate not only on the cognitive level of functioning, as is observed in classical CBT work, but also on the emotional level. As was already stated in the review of the literature, changes in the emotional level of functioning are crucial for a long-lasting improvement of functioning in patients [27]. At the same time, it is important to emphasize that the ideas described above are only hypothetical, and need empirical verification, especially since there is promising but very limited data on the effectiveness of ST in eating disorders.

SCHEMA THERAPY IN THE TREATMENT OF ADOLESCENTS WITH ANOREXIA NERVOSA: CONCLUDING REMARKS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

As was stated at the beginning of the article, according to the NICE recommendation in adolescent patients suffering from AN family-based treatments, individual eating disorder focused cognitive-behavioral therapy or adolescent-focused psychotherapy for AN should be implemented [23] and, while taking into account the rather unsatisfactory effectiveness of those methods, new approaches should be introduced in this group of patients as well. Taking into account the life-threatening and harmful effects AN has on the physical and mental health of an individual it is important to conduct further research on the possible application of ST as a treatment method for adolescent AN patients, especially since there are some studies showing this method of work might be useful in this group of patients [168].

Since there is evidence that AN is difficult to treat with classic cognitive-behavioral therapy, and is accompanied with high drop-out rates along with debatable efficacy rates [e.g. 169, 170], it seems worth analyzing the applicability of ST within this group of patients. There is evidence that Schema Therapy has been effective for all sorts of patients suffering with complex mental problems, including eating disorders [171]. It is well suited to patients who have experienced emotional neglect, abuse or trauma, and has also been proved to be effective with teenagers [172]. This therapeutic approach is strongly recommended, in particular, for people who did not benefit from other standard therapeutic methods [27]. It helps individuals to notice and address the feelings and emotional needs they experience experiences. With various image-based and behavioral techniques it supports the process of development and strengthening of the healthy adult mode that remains necessary for adequate emotion regulation [170], which is indispensable while working with patients suffering with AN [67].

It is also worth emphasizing here that only a theoretical analysis has been presented. Empirical studies are needed in order to verify whether Schema Therapy might serve as a treatment method that could be more effective than other interventions. More specifically, the hypothesis stating that early maladaptive schemas in the adolescent population serve as a predictor of AN should be verified. Empirical studies should be conducted in order to confirm whether limited reparenting is the most important factor and is especially useful in the therapy for adolescents suffering complex relational problems within their family systems. Some research should be also devoted to the analysis of probable differences between adolescents and adults suffering AN and treated with ST. Last but not least, more research on the efficacy of Schema Therapy in teenage patients suffering AN, including clinical and subclinical groups of patients, is needed.